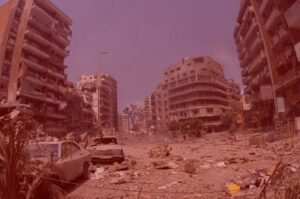

Rima offers readers an understanding of Beirut as both a single city and a city multiplied, a geographic point always undergoing change.

“The cycle of life runs to a self-evident rhythm in this city. Beirut’s soil is composted of layer upon layer of lives that have passed on … it is a city that does not advance in time but rather in accumulating layers, a city that will sink as deeply in the earth as its edifices tower high. How many cities lie beneath the city? How many cities lie there to be forgotten?”

— Hoda Barakat, The Tiller of Waters

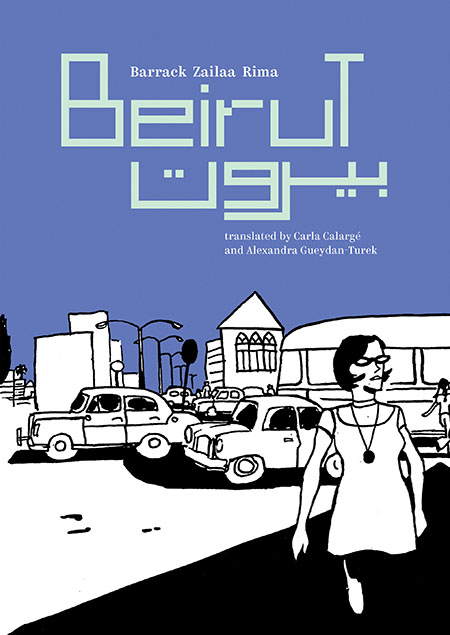

Beirut by Barrack Zailaa Rima

Translated by Carla Calargé and Alexandra Gueydan-Turek

Invisible Publishing 2024

ISBN 9781778430480

How does an artist begin to account for the “accumulating layers” that compose life in Beirut? As the Lebanese author Hoda Barakat suggests in the provocative title of her 2000 novel, the acts of documenting, sense-making, and transmitting are akin to tilling water. The tiller surfaces something new at every instant, only to have it flow back into the whole once again. Tilling water might seem to be a fruitless exercise, but as Barakat and Lebanese creators before and after her demonstrate, this ephemeral, effortful activity is perhaps the only way to observe, mourn, and hope for the city they love.

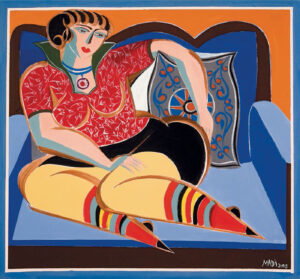

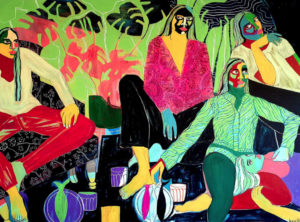

With the graphic novel Beirut, Barrack Zailaa Rima joins these persistent tillers of water, making a compelling case that the form of comics and the genre of magical realism might be best suited for such a demanding task. Rima offers readers an understanding of Beirut as both a single city and a city multiplied, a geographic point always undergoing change. To keep up with this mercurial entity requires a playful relationship to form and genre, one Rima demonstrates in spades.

Beirut is a single graphic novel, published in 2017 and translated into English in 2024. It is also three separate comics: Beirut (1995 [2013]), Beirut Bye Bye (2015), and Beirut Rewind (2017). The text’s complicated relationship to form — is it a trilogy of texts? An anthology? A single volume with three chapters? — is only appropriate for its chosen subject.

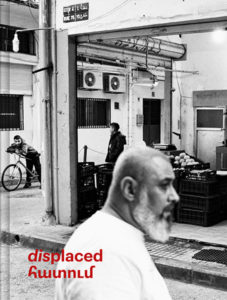

In each comic, Rima offers small snapshots of what the city’s “accumulating layers” even as yet another layer — of garbage, of political corruption, of the cracks in the confessional system — already threatens to overwhelm both the urban inhabitants and the artist. Rima’s documentation can only be snapshots because the Tripoli native has lived outside of Lebanon for decades. Each narrative focuses on one of her visits back to Beirut, allowing her to focus on what she finds altered and what remains constant.

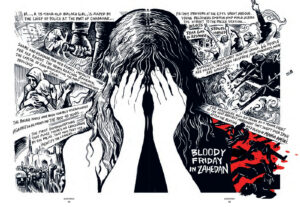

Reviewing Beirut for an issue on genre fiction is especially fitting, with an important caveat. As comics theorists assert often and with force, comics and graphic novels are not in themselves a genre. Rather, “they are a vessel for expression, a holder of meaning.” As a form, comics challenge readers to draw connections between language and visuals. It demands readerly participation while offering creators radical opportunities for ambiguity and exploration. What makes comics such a compelling art form is the way they adapt and contort to contain a host of genres. Inside the graphic novel are unlimited possibilities for narrative structure and graphic representation, possibilities Rima exercises with visible abandon throughout Beirut.

In a recent interview, Rima describes questions about genre as “my favorite,” describing the play among genres as integral to her work:

“The distinction between documentary and fiction does not suit me. In a documentary story, there are always choices, frames, selection, and therefore a subjective part. In fiction, we project ourselves into the characters and the story, consciously or not, and we always tell very real facets of ourselves and the world. I obviously don’t want to make this a dogma, nor pretend that this is the case for everyone. But as far as I am concerned, I am attentive to the fluidity between genres and the possible paths in one direction or the other.”

Rima’s answer disrupts attempts to categorize fact and fiction. However, it is her work that teases out these complexities even further. Through nightmarish images and narrative that frequently unfolds at breakneck speed, Rima suggests that documenting Beirut’s lived realities is only possible through the lens of the phantasmic. Making sense of living in Beirut, remaining in Beirut, and leaving Beirut practically require an attunement to its surreal qualities. Writing about Beirut is always an exploration of the magical and the real — it requires a willingness to exist in multiple places, times, and experiences at once.

Rima is not alone. Others before her have drawn on a magical realist vocabulary to document the city — one needs only think of Ghada al-Samman’s horrific Beirut Nightmares. And if you haven’t yet seen Mounia Akl’s Submarine, stop reading this review immediately and spend twenty minutes with the haunting short film, which imagines a mass evacuation in response to overwhelming garbage.

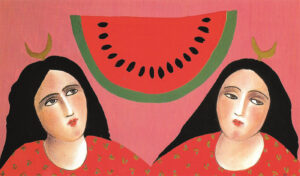

Rima’s work is in conversation with this lineage of surreal artistic production, even as her project remains deeply personal. Yet another binary Beirut challenges is that of leaving and remaining — Rima is drawn back to the city over and over, whether through family obligation, professional expectation, or the desire to document. From this perspective, which is emphatically neither inside nor outside, Rima retains an ability to identify the absurd — and, with her vignette style, resists larger narrative meaning-making or closure.

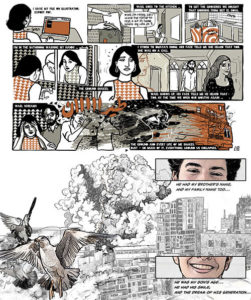

The text’s first comic, Beirut, was published in June 1995 and then reprinted in 2013. This first piece peers into a potentially hopeful future: “Like many Lebanese expatriates, I was preparing to move back home full of expectations, yearning to create a bande dessinée in this country that had just emerged from the civil war,” Rima writes. The comic skips across the city, pausing among the nostalgics and the reflectives. The comic echoes The Inferno in the way our narrator guides us through the city. “I am the last hakawati in Beirut,” he declares. “A hakawati tells stories. Stories that come from the past … But I won’t tell you about the legendary lovers Qais and Layla. I will tell you the stories of my city.”

Our hakawati makes good on his promise as he pauses to observe old architecture, transportation across the city’s carts, buses, and cargo ships, and the stories of Beirut’s residents. A dreamlike interlude based on Fayrouz’s “Habibi bado al-qamar” gives way to an imagined conversation with Oum Kalthoum. As we careen through the city, Rima carefully etches residues of conflict on buildings. In one particularly striking scene, a branching tree explodes across the panels, charging a former resident with abandoning his home during the war. The lines spill off the page, a stark call to contend with an ever-spreading history.

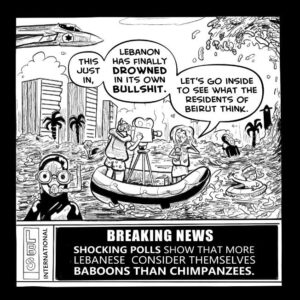

Rima’s first piece is a dreamlike, if sometimes nightmarish, ode to a city on the brink of something new. By the second, Beirut Bye Bye (2015), those threatening undertones have reached a fever pitch. Depicting herself as a father visiting the city with a wife and small child — Rima transitioned to she/her pronouns in 2021 — the narrator attempts a journey to the waterfront. Once there, the presence of cranes, helicopters, and skyscrapers becomes overwhelming. Designating the entire city “private property,” armed guards force residents away from the water.

Characters echo throughout the three texts. A reference to Handala in “Beirut” — Naji al-Ali’s iconic cartoon image of a young Palestinian boy seen from the back — reverberates in Beirut Bye Bye’s depiction of a young man standing by the sea with his hands in his pockets, for example. Similarly, the hakawati of the first piece reappears here as a city taxi driver, rescuing the family from conflict and driving family members through an apocalyptic Beirut. As they drive past a book burning, Rima highlights the cover of a Samandal issue, deeply conscious of the way this art form threatens political hegemony. The family’s horrific descent continues into mounting garbage before finally managing a flight away. The final full-page illustration depicts their silhouetted airplane taking off from a Beirut on fire.

By the third and final comic, Rima appears to have determined that the only way forward is back. Published in 2017, Beirut Rewind accompanies Rima on a visit to the city for a book release. On this trip, the narrator once again encounters the hakawati taxi driver, who has now added “Beirut, the jewel of the Orient” and “Beirut, the beating heart of Pan-Arabism” to the list of myths he refuses to tell. The hakawati drives Rima past downtown reconstruction, a nod to the era of reconstruction and downtown development by companies like Solidere that has led to further amnesia, historical rewriting, and political corruption.

At the book launch, the narrator’s mother appears, ten years after her death, and reader and narrator alike suddenly time travel to 1967, the year Rima calls “the source of my mother’s ideals and my disillusionment.” In watching the young activists of 1967, Rima lingers both on the ways they failed to reach their objectives and the ways they provided a roadmap for continued generations of protestors.

Rima’s final two comics both end in departure, or perhaps more accurately, an escape. Just as the family of “Beirut Bye Bye” flies away as their story concludes, the hakawati helps the narrator clamber out of the past through a collection of books. Titles like Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness, multiple Samandal issues, and I Remember Beirut highlight the lineage of writing and creating about the city that anchors this protagonist.

In Rima’s final journey with the hakawati, they drive through a nondescript black background. In the foreground, Beirutis hold up signs protesting a range of political ills, including protests against government mismanagement, the confessional system, the kafala system, the bans on civil marriage, and artistic censorship. To see these protests sharing the same comic panel highlights the fullness of governmental failures — and the possibility of what is accomplished when activists recognize these fights as linked.

Rima hazards no guesses about the future in store for Beirut and draws no conclusions about the current protests. As an avowed “outsider-insider,” Rima somehow observes both intimately and from a distance. In the form of the comic and the play across genres, Rima embraces these contradictions.

“You have — at the same time — an instant and a duration on the same page,” she says. “You have the sequence and the singular moment. You also have the contrast between the text and image, and the time it takes to read them: to read an image it takes an instant, but to read a text takes time. You also have the contrast between the outside and the inside. What you call here, outsider-insider, it’s not only outside in the sense that I am far from Lebanon, and inside to mean that I am in Lebanon. It’s also the visible and the invisible. In Sufism they say, al-zahir wa al-badin, that which is revealed to us and that which is hidden. In comics, there are a lot of things which are hidden. So all of these dichotomies play a role in this story.”

The pleasures and challenges of Beirut depend on the reader’s ability to pursue the hidden, to linger on the billboards, license plates, and signs that clue us into the discontent simmering under the surface of even idyllic scenes. This is a book that asks readers to accept the surprising arrival of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, who stand in as government representatives, and to pay careful attention to echoes across time and space. Beirut is hard work for the reader, but the reward is a deeper connection with those “accumulating layers” of complexity and place.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)