Middle Eastern Women’s Coded and Uncoded Writing on Love & Sex

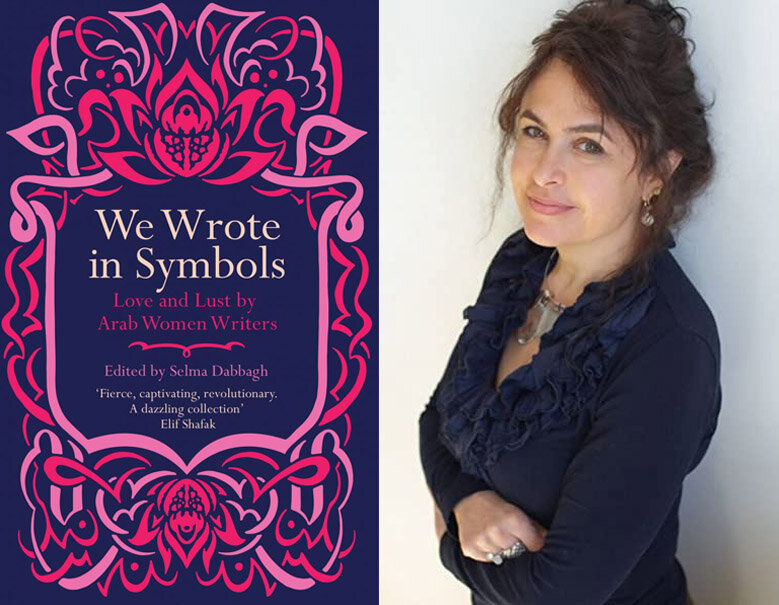

We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers

Edited by Selma Dabbagh

Saqi Books, London (April 2021)

ISBN 9780863563973

Malu Halasa

“Does a toothless mouth really need a toothpick?” That’s how Zad-Mihr mordantly described lovemaking with her fat-lipped slave master, Abu Ali ibn Jumbar, who abandoned her in the backwater of Basra for debauchery in Baghdad. More than ten centuries after she came up with that timeless put-down, Zad-Mihr’s vitriolic words still chime with women the world over. Slavery has been outlawed but patriarchy is in full force. So is bad sex and male self-delusion. Some things, it seems, never change.

Encouragingly what also persists is the wit and insight of generations of Arab women. For We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers, the novelist and radio playwright Selma Dabbagh has brought together 101 poems, short stories, fiction, letters and word play by 73 contributors from the Middle East, North Africa and the diaspora. Zad-Mihr is one of them. Her life and letters were recorded by a male author in Abbasid Iraq known for the only book of his to survive from the 11th century, about a gate-crasher of parties in Baghdad.

Alongside the medieval Islamic women poets, singers and slaves in We Wrote in Symbols are the leading lights of modern Arab fiction: Hanan al-Shaykh, Ahdaf Soueif, Leila Slimani and Adania Shibli — long listed for this year’s International Booker Prize. The anthology also features a generation of new writers, which includes translators, activists and performers.

Life at Court

The book’s title comes from a line of love poetry written by Ulayya bint al-Madhi, an accomplished poet and singer in the court of her half-brother, Caliph Harun al-Rashid, who reigned at the height of the Abbassid period, scenes of which were recounted in The Thousand and One Nights.

Of the many poems and songs Ulayya composed during her lifetime, only a handful survives. Little is known about the dissemination of these poems and others composed by women. Innuendo and scandal fueled the rumor mill of courtly life. Haroun al-Rashid encouraged his half-sister to sing, but with reservations. He ordered her to not name her eunuch lover in her songs, so she called the man she loved by a woman’s name, instead.

The writing of love poems by women ended with the fall of Muslim Spain. The flowering of culture, which provided a space for women’s writing, was replaced by a new entrenchment and religious austerity that curtailed the lives and voices of women — and not just that of the Arabs’. The same rupture took place in Jewish women’s writing after 1492.

Breaking the Silence

The five hundred years of silence that followed was broken by coded writing on courtship and arranged marriage in 19th century novels from Egypt and the Ottoman Empire. By the 20th century, migration and exile, displacement and war had created more spaces in which women wrote in different countries and languages. The modern fiction in We Wrote in Symbols reveals a dizzying array of modern love, aspects of which would have been lost on the medieval women poets.

In Malika Moustadraf’s short story “Housefly,” a wife engaging in internet sex returns to her husband in the living-room, who retreats behind a closed door to spend ‘me time’ on his computer. In another short story, “Lovers Should Only Wear Moccasins,” by Joumana Haddad, despite preparations — no panties — a woman makes an unremarkable visit to a swingers’ club in Paris. The adult circus in Rasha Abbas’s story “Simon the Matador” is more of a mind than a body fuck, with an over-thinking female protagonist talking herself into and out of S&M.

Some stories celebrate queasy sex like Samia Issa’s voyeuristic account of men watching and listening to a woman masturbating in a public latrine in a Palestinian refugee camp. Explicit writing about sex is not necessarily heroic, feminist or politically enlightened. In other stories women authors adopt the point of view of predatory men and cover the ugly faces of their female characters with bags.

Hanan al-Shaykh’s short story in the collection is “Cupid Complaining to Venus.” A woman and her lover watch films suggested by the woman’s girlfriend. After uncomfortable sex in the fetal position, the character, a writer, goes and gives a literary reading, during which she realizes, “I had found someone who would take my face in his hands and let me lie the way I wanted to. I saw him even though my eyes had not left the page. But his eyes grazed my skin, and started heating up my blood.”

Stories about sexual encounters at weddings; life-giving orgasms after bereavement and mystical couplings in the desert have been written by anonymous writers. The excerpt from the novel The Almond: The Sexual Awakening of a Muslim Woman by Nedjma, another pseudonym, is too dangerous to publish under a real name in the Maghreb, where Nedjma is from, and where sexual scandals in countries like Morocco have been used by the state to censor and silence journalists.

The Living Past

For modern writers, the past history of the region still inspires — like the illicit swim before sex, from Randa Jarrar’s Map of Home, “to those sunken subkingdoms and cities of Heracleion and Canopus where I touched the statues’ eyes, watched their dead-awake faces. I saw pink granite gods, and a sphinx of Cleopatra’s baba, Ptolemy XII … a green statue held … something huge in its hand. I couldn’t tell what it was until I swam closer; it was a pen.”

Yasmine Seale translated “What is its Name” by another “Anonymous,” taken from “The Porter and the Three Women of Baghdad” in The Thousand and One Nights. What do you call the vagina? “Mound,” “sting” or “Bridge of Basil”? Seale reveals something rebellious and modern in text from the eighth century.

The Thousand and One Nights were folktales, which like moss picked up stories and influences from Arabia, Persia, Mesopotamia and India. The tales, filled with unreliable narrators, were framed by a woman, who told stories night after night to her groom-king-murderer to stave off her own execution in the morning. The question remains: who wrote them? If, for the purposes of We Write in Symbols, we believe that men did not write The Thousand and One Nights, does that mean women were its main intended audience? Or, more subversively, were men meant to hear them, enjoy them, and then understand a female perspective and the value of women’s intelligence too?

The translated poems and stories from the Golden Age of Islam by Seale and older, male translators — Abdullah al-Udhari, Wessam Elmeligi and Geert Jan van Gelder — contribute a significant amount of material to We Wrote in Symbols. The earliest poem in the book comes from the pre-Islamic Jahiliyyah period. Another slave Jariyat Humam ibn Murra yearned for the bald head and the urine of her lover. He killed her. On entries like these, dates would have useful, although some contributions immediately speak to contemporary sensibilities of resistance and ingenuity.

Modern Sensibilities

Poet, performer and activist lisa luxx’s poem, “to write the wrongs of centuries, we must brew our own tools,” includes the line: “they call this lesbian /I kiss your knee and call you comrade …” Another poem “Arachnophobia” is a reflection on missed love. Hoda Barakat covers ground in the passage from her novel Stone of Laughter, which captures the sexual tensions of relatives living on top of each other, during the Lebanese civil war. It is this conversation between the generations of writers that make the anthology worthwhile.

Unrequited love has always been the greatest theme of the Arabs. In Sabrina Mahfouz’s poem “TALI: one day when I worked at the bakery,” a young woman at the cash registers imagines herself as girlfriend-mother-lover of some guy paying for his sandwich. He’ll never know her name or remember that they’ve ever met; desire is all in the mind.

Just because Arab women write more forthrightly about sex, don’t be fooled into thinking that lives inside and outside the region are freer or more open. Dabbagh leaves her readers with a final caveat: “To try to pretend that the Arab world has experienced a sea change in its approach to women’s sexuality would be a misrepresentation.”

For many of the contributors, however, change has come and they’re done with tolerating male chauvinism and antiquated attitudes, which should have been ditched centuries ago. Zeina B. Ghandour’s poem “You Cunt” lances the notion of the male gaze, with all its contradictions, including female complicity.

Writing like this gives We Wrote in Symbols tension, edge and humor.