The field of heritage preservation widely acknowledges that the process of reconstruction can have equally detrimental effects on historical sites as disasters and conflicts themselves. In some cases, it is argued that reconstructions can cause even more harm, as they prioritize authenticity over the cultural meaning of monuments and artifacts.

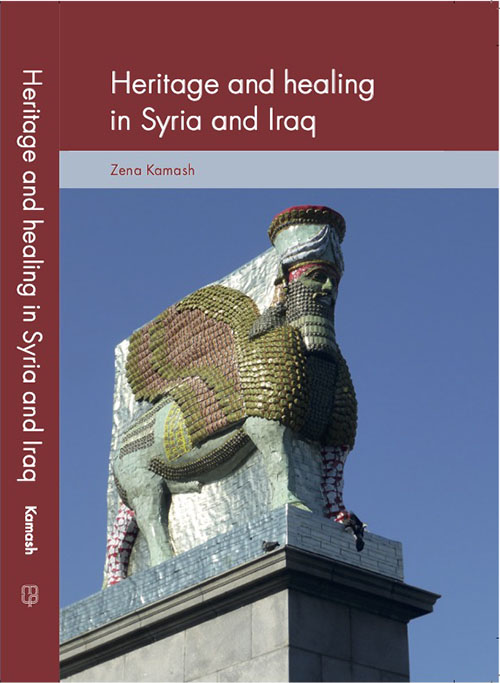

Heritage and Healing in Iraq and Syria, by Zena Kamash

Manchester University Press 2024

ISBN 9781526140838

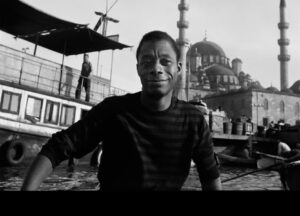

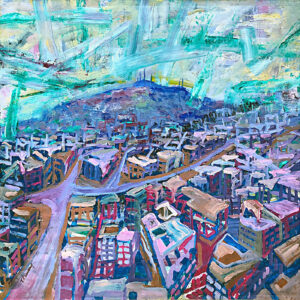

Last year in February, the city of Antakya in Turkey and its surrounding region were almost completely destroyed by the massive earthquake that rocked a vast region between Central and Southern Anatolia and the northern Levant. Foster+Partners, a major British architectural firm, was enlisted to lead the reconstruction, together with other local and foreign architectural practices. The plan would be part of a wider design-led revitalization of the city, spearheaded by a local NGO, the Turkish Design Council. A masterplan was revealed at the end of July this year, covering a 30-square kilometer area, touching on aspects such as “retaining the cherished spirit of the town and pre-earthquake characteristics in terms of scale, relationships, and configurations” and “building anew in a way which makes the residents feel like they can be at home in a revitalized city.”

Antioch, as it has been known for most of its history, has survived as many as seventy earthquakes since its foundation in the 4th century BCE, but few as devastating as the quake last year. When a series of digital renderings of a proposed reconstruction surfaced online in 2023, they caused an uproar among the community of Antiochians and urban experts in the country: they objected to these clean, sanitized spaces of consumerism, punctuated by the square lines that screamed gentrification and resembled other poorly executed restoration projects in Turkey.

What was disturbing about the digital models was not simply that they did not resemble in any way the vernacular heritage of the city, the result of centuries of syncretism, multiculturalism and architectural ingenuity. It was the fact that the imagery of these sleek, uncontaminated spaces contrasted sharply with the reality on the ground; the old city of Antakya was at the time a formless mass of toxic rubble, ancient stones, human remains, collapsed walls and steel frames, forming a thick archaeological layer turned upside down, and nearly its entire population had been displaced — not unlike what has happened in Gaza. Old Antakya has now been bulldozed and demolished into a desolate flatland.

But this isn’t just any other reconstruction. According to Mehmet Kalyoncu, chair of the Turkey Design Council, the Turkey-Syria earthquake rebuilding is “the most sophisticated urban problem in the world today,” judging by the scale of the area affected, which is as large as the entire size of Germany. A natural disaster, it could be argued, was unavoidable, but there are different types of violence that destroy cities and heritage other than violent conflict. We are looking here at a combination of urban and environmental violence, neglect and lack of political participation.

During a conference in Antakya in June, one of the architects at Foster+Partners, Bruno Moser, said that the involvement of locals in post-disaster rebuilding is crucial for recovery from trauma, and that “the process of being part of the rebuilding and regrowing, healing is a big word, but I think there’s something healing when you’re helping to bring a place back.”

But can healing, closure and reconciliation really happen through buildings alone? The experience of cities in the region suggests otherwise. It’s not only the infamous case of the Beirut Central District, completed in 2005, and now a ghost town for the mega-rich, but also Diyarbakır or Istanbul, cities in Turkey that have witnessed large reconstruction projects of both monuments and urban areas, so aggressively and unilaterally executed that a journalist has aptly called them re-destructions.

It is almost an established fact in the heritage parlance that reconstructions are as destructive as conflict, and sometimes even more.

A recent book by Iraqi-British archaeologist and artistic practitioner Zena Kamash, Heritage and Healing in Syria and Iraq (2024), looks at the experience of Iraqis and Syrians, who have suffered devastating violence and destruction to their cities and cultural heritage over the past two decades. She asks the difficult but essential question of whether simply rebuilding or restoring immediately is always the most helpful and sensible approach that serves the needs of grieving communities.

With a focus on the cases of Tadmor-Palmyra and Mosul, Kamash argues that although buildings need to be rebuilt, because “cities cannot be left as piles of rubble,” the heart of the matter lies in the kind of activities that these buildings and artifacts facilitate. The relationship that buildings and monuments enter into, will be the defining measure of their success; there’s a co-production of reality between peoples and their built environment.

But as Kamash points out, the original reasoning behind reconstructions is not always simply allowing people to return to “normal,” and this needs to be examined in detail: “When a building dies, smashed to pieces in a deliberate act of violence, the reconstructionist qua preservationist knee-jerk response is immediately to claim: we will bring it back to life!”

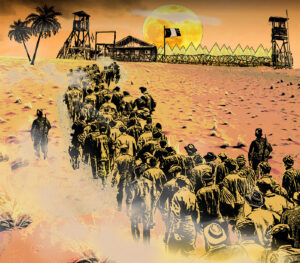

But there’s more than meets the eye, as Kamash argues. “The proposed reconstruction and rebuilding projects become flags on the moon, staking control over a territory and its narrative.” People are often met with accusations by governments and agencies that they do not know how to rebuild their own cultural heritage, and are not capable of shaping their own narratives. The greatest examples, amplified by Western media, came in the face of the destruction caused by Da’esh in Palmyra and Mosul, when the fate of archaeological sites and antiquities was prioritized over the fates of peoples enduring displacement and often death. They would become dehumanized twice — first by their victimizers, and then by their self-appointed saviors.

Countless articles from 2015 devoted to the fate of Assyrian antiquities in the museum of Mosul and the destruction of the Roman-era arch of Palmyra, conveniently ignored that destruction and plunder of antiquities is hardly an innovation of Da’esh. Colonial powers, authoritarian regimes and treasure hunters have long looted and hammered down archaeological sites in the region, but the extractive violence of Europeans in the 19th and 20th century remains unmatched: entire temples, gates and palaces were disassembled brick by brick, their walls laid bare, and their contents shipped to form the collections of encyclopedic museums.

And then there’s another type of colonial violence that makes the contemporary spectacle of bulldozing antiquities, a political response to the colonial past: the epistemic violence that isolated archaeological sites from the dynamic present they were part of, depicting them as a fossil frozen in time, narrating the genesis of the Western world, and often used as tools of oppression by colonial powers and later authoritarian regimes.

When the earthquakes rocked Antakya in 2023, the headlines returned, mourning the destruction of one of the most important cities for early Christianity, but they also exposed the paradoxes of epistemic violence: For all its ancient, Western pedigree, in the century since Antioch has been excavated by Western archaeologists, even though the location of the ancient city is known and many of its floor mosaics can be found in many American museums, none of its major churches, bathhouses, and temples, known from literary sources, have ever been found, a result of difficult topography, destruction by earthquakes, sedimentation and long-term neglect. In the absence of a major temple to save and reconstruct, and with a beleaguered population in need of housing and public services, the story quickly disappeared from the headlines.

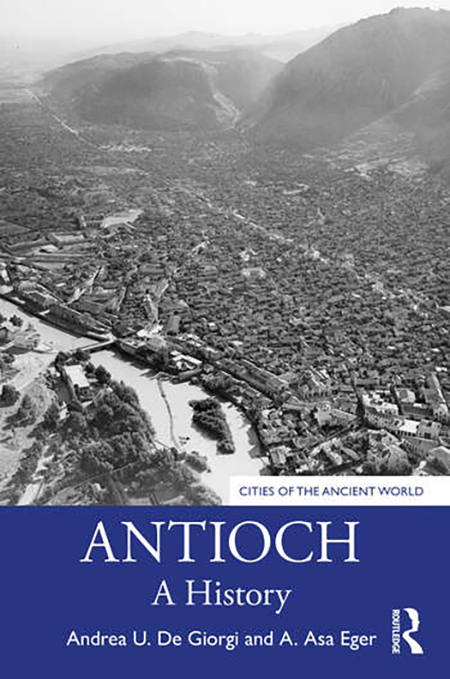

The real heritage of Antioch, however, as Andrea di Giorgi and Asa Eger argued in their monumental Antioch: A History (2021), is the lives of its peoples and the ability of the city to reinvent and transform itself in every generation. Di Giorgi and Eser tell us that traditional accounts of the city in Western historiography end with its destruction by an earthquake in the 6th century CE, after which it was allegedly abandoned. But the truth is that it continued to thrive during the Early Islamic, Middle Byzantine, Seljuk, Crusader, Mamluk and Ottoman periods that followed, comprising more than twelve centuries to the present. Kamash and her colleague Jennifer Baird, made a similar argument about Tadmor-Palmyra a few years earlier.

But Kamash’s book is eye-opening in its attention to details about Iraqi and Syrian heritage that have remained obscured in the media narrative: The number of mosques and shrines destroyed by Da’esh in Mosul surpasses the ancient monuments in great numbers, and the great destruction caused by liberation forces remains practically unheard of. Militants understood well the emotional value of ruins for Western audiences; value they didn’t grant to Islamic monuments destroyed either as punitive measures or seeking to destroy communities they perceived as heterodox or deviant in Islam.

One of the monuments that was destroyed by Da’esh in Mosul was the Great Mosque of Al-Nuri, blown up during the Battle of Mosul in 2017, and an iconic building from this period because it was there that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of Da’esh, declared a caliphate in 2014. A reconstruction of the mosque has been underway since 2018, with funding provided by UNESCO and the United Arab Emirates, one of the key geopolitical actors in the region. The new mosque is slated to open at the end of 2024. When reconstruction projects are set in motion, Kamash tells us, “In the context of reconstructions and rebuildings, authenticity is often regarded as the gold standard, but what do we actually mean by it? How do we achieve it? Should we be aiming for it at all?” The question of authenticity reduces monuments to a single moment in time. But which exact moment should be chosen over another and why? Who decides? Kamash mentions a combination of white savior’s mentality, infrastructural colonialism and technological solutionism, running throughout the ideology of reconstruction.

Many reconstructions attempt to cover the fresh corpses with make-up and pretend that we were not collectively faced with the mortality and fragility of our own world. When Antakya was destroyed, countless people were buried under the rubble, and are to this day declared as missing. It is impossible not to draw parallels here with the bodies under the ruins, in the ongoing urbicide in Gaza…

In her book, the Iraqi-British scholar describes in detail the incredible history of the mosque and its many additions, renovations and reconstructions. The complex was founded by Atabeg Nur al-Din Mahmud Zengi in the 12th century but a reconstruction was already documented in the 15th century. Two hundred years later, it was in considerable disrepair and used as a dump. Restored in the 18th century, it was again ruined a century later, and a major reconstruction began in 1864-1870. Further reconstruction continued in 1913-1918, and after 1925, more repairs were added. The main building was subsequently demolished and rebuilt in 1945-6, and then partially expanded in 1956. Stabilization works were carried out in 1980-2, and the prayer hall was remodeled in the 1990s. Kamash tells us, “This is, then, a story of edits, adaptations, demolition and rebuilding.” To which specific moment in time is the reconstruction referring then? The lasting value of a mosque as a public space lies not in its authenticity, but in the accumulation of social memory and experienced time.

A similar situation is underway in Antakya with St. Paul’s Greek Orthodox Church, an iconic landmark of the city, destroyed during the earthquake. Although tradition tells of Saint Peter and Saint Paul preaching the Gospel in the city, all the tales that associate the church site with antiquity are apocryphal. But that does not mean that the 1872 building does not hold importance in the historical memory of Antiochian Christians (the original building dates back to 1830 and it was destroyed in an earthquake). The site itself is so important for the community that a number of high-profile religious services have been conducted on its ruins since 2023. But does the new building, the reconstruction of which is overseen by the World Monuments Fund, have to be exactly in the likeness of the old, which wasn’t that old after all? It is important to remember that ancient restorations of monuments, which took place many times in the past, did not necessarily strive for authenticity and always incorporated new technical, architectural, and functional elements.

In a press release by Foster+Partners, about their vision for Antakya, they tell us that, “The practice focused on re-establishing the pre-existing characteristics of the area and enhancing them, aiming to encourage displaced people to return.” I will circle back to the mystified notion of the pre-existing characteristics, but a bitter truth that obviously must be known to the developers is that displaced people will likely not be returning. Through the legal figure of “reserve areas,” the government has effectively suspended property rights in large residential areas of the region that it has arbitrarily determined to be at risk of natural disaster, paving the way for the expropriation and displacement of ancestral minority communities, a process that began through district gerrymandering decades ago. It is said that people will receive compensation for their property, but it is not clear when or how, or whether it will be only in the form of loans, as it was the case in Istanbul, where the reserve areas after the 1999 earthquake were ultimately used in the past to build profitable developments and shopping malls.

Can there really be healing through expropriation and permanent displacement? As Kamash’s book underscores, drawing on trauma theory, for healing to happen in communities that have been devastated by destruction, actual healing work needs to take place. “Essentially, traumatic memories have not been fully digested by the mind and, therefore, cannot become narrative memory,” Kamash writes. Trauma needs to be fully acknowledged, and to simply clean up and rebuild is not acknowledgement, but rather, a form of repression. And repressed trauma will continue coming back, “[b]ecause traumatic memories have not been fully incorporated into the experience of the person or collective, they can seem out of time, an unchanging past that is always present.” A shortcut approach to reconstruction means, in Kamash’s words, healing without therapy, something that is not possible.

And the focus on “re-establishing the pre-existing characteristics” is intimately tied up with the possibilities of healing. Kamash writes:

Why are people so scared of ruins, especially those that come from conflict? Buildings have a veneer of permanency and solidity in our lives. They often outlast us, sometimes for many centuries, making them seem immortal and everlasting. Coupled with this, […], our archaeological narratives that emphasize continuity over disruption and change feed into this dangerous illusion. This is a mirage; buildings, and the places they make up, are in constant flux and those seemingly immortal structures that survive so long do so because of a series of intricate choices and accidents. In addition, the longevity of some structures masks to many people (with the possible exception of archaeologists and historians) how many have not survived.

Many reconstructions attempt to cover the fresh corpses with make-up and pretend that we were not collectively faced with the mortality and fragility of our own world. When Antakya was destroyed, countless people were buried under the rubble, and are to this day declared as missing. It is impossible not to draw parallels here with the bodies under the ruins, in the ongoing urbicide in Gaza, where the scale of destruction and death toll, make it impossible to imagine meaningful reconstruction processes that do not propose innovative ways to think about heritage that might translate into different approaches to rebuilding other than either forced amnesia or the chronic repetition of the past.

In the seaside town of Samandağ, near Antioch, people have held mourning rituals, marching quietly with myrtle branches and incense censers, chanting that they’re still alive. In my mind, these are mourning rituals not only for the lives lost, but also for the buildings, the landmarks, the squares and the aggregate of relationships that were interwoven with them. We know that the dead cannot be brought back to life.

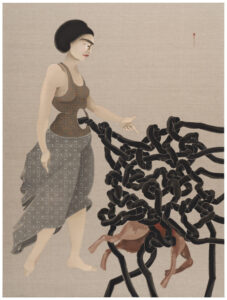

Kamash tells us about the creation of reconstruction zombies: “Yet, keeping the dead alive, or at least trying to, has the effect of falsely stopping time, or trying to cheat death and that, as any viewer or reader of horror knows, leads to zombies.” She adds, “But there is an alternative; we could, instead, mourn and let that building or object go with dignity.”

When Sevcan, a mother from Samandağ, recounted the demolition of her building in the seaside town of Çevlik, which had collapsed and obviously couldn’t be rebuilt, she expressed that the grief was infinitely larger than the moments of the earthquake, because this departure was now final, but “letting go and mourning need not necessarily mean forgetting,” argues Kamash. “There is the potential for this letting-go of the physical form to become a site of deep creativity and healing.” The building might be gone, but the networks of relations and lived memory are still intact, but the process does not work inversely. The container cities built for the refugees by NGOs, far away from the city center, lie still empty. People refused to part from their ancestral lands and their neighbors, even if it meant living in tents and makeshift arrangements and dilapidated apartments.

The materiality of the place remains an essential form of sensorial attachment. “What is left behind after a monument is destroyed? Is it simply an empty space, a void, a gaping nothingness? […] On a physical level, there is always something left behind, even if that something is rubble. That rubble still has material substance and is a reconstituted version of the monument’s material: the monument in a different form. But there is also something less tangible left behind: all the memories linked to the place and all the potentialities that were in that monument’s future. These, I think, are the ghosts.”

Borrowing the idea of ghosts from the work of French philosopher Jacques Derrida, referring to something that is neither alive nor dead and that therefore cannot be killed, is Kamash’s novel proposal for rethinking the practice and ideology of reconstructions in terms of not attempting to falsely freeze time. But what would these ghosts in terms of reconstruction projects look like?

There are no easy answers, but what is clear is that reconstruction should refer not only to the built environment, but also to personal and communal narratives, ephemeral public spaces, modes of deliberation, oral memory, cultural expression, and more. The monument and city as a museum is an attempt not to heal, but to circumvent conflict.

But there’s one project, for example, 20 km north of Antakya, at the archaeological site of Tell Atchana, the Middle Bronze Age city of Alalakh, that has turned a decades-long excavation into a participative heritage site in the present. When the site sustained significant damage during the earthquake, and the millennia-old structure was in need of extensive restoration, archaeologists involved the local community in the process, recruiting their help to produce mud and hay bricks, made from local clays and baked in the sun, with the same exact features of those bricks made in the region over thirty centuries ago, to restore the site not only from the earthquake damage, but also from the destruction caused by colonial excavations in the 20th century exposed by the earthquake.

If the experience of Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Gaza has taught urbanists anything, it is that the camp is no longer a transitory figure and therefore should be empowered as the starting point of communities and new urban imaginations, rather than simply regarded as a temporary, necessary evil. The refugee camps, the tent and container cities, and the rubble itself, can be strengthened into political spaces and memory sites and perhaps they must remain in full view (as I argued in “Meditations on Occupation, Architecture, Urbicide“ in TMR in 2023) as a testimony of the complex social and urban assemblages that violence attempted to erase.

It is estimated that the execution of the masterplan for the reconstruction of the center of Antakya might last ten years, and for the rest of the city estimates are as long as three decades. Can a urban arrangement really be called temporary housing when traumatized populations will inhabit it for as long as a generation?

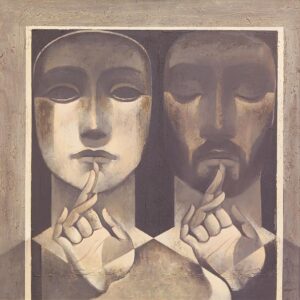

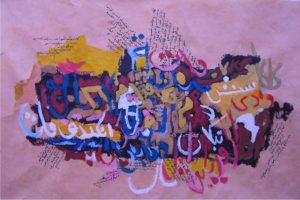

But ultimately, the idea of heritage reconstruction as a territory of ghosts, is not simply a function of spatial distribution, but the recognition that healing communities requires patience and time, and can take on many forms. Drawing once again on trauma theory, Kamash proposes art as one of them, and sheds light on her own artistic practice with textile art, part of a therapeutic process through which she was able to process some of the emotions involved in heritage reconstruction. Her triptych “Hatra and Mosul” (2021), represents three phases of heritage in Iraq — before, during and after Da’esh. “Each archway element bleeds into the next as a reminder that each phase is inextricably linked to what came before and what will come after,” she emphasizes.

Kamash also mentions other practitioners such as Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari, alongside the work of activists, archival practices, heritage collectives, online archives and philanthropies. But she specially sheds light on the work of Michael Rakowitz, the Iraqi-American artist, whose work is very well known in the West and has tackled the challenges of heritage and healing, in often graceful, thoughtful ways. I have already devoted an essay to the work of Rakowitz in TMR in 2022, but there’s a story mentioned in Kamash’s book that is worth retelling. In reference to the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, dismantled and later rebuilt at the Pergamon Museum, the catalog for Rakowitz’s exhibition On Rage tells us: “There is no real Ishtar Gate. Its powerful presence disappeared when the German archaologists, Koldeway, carried it from its original site.” Is this perhaps another way to think about heritage instead of torturing ourselves with unreachable, contested, moving pasts?

For Antakya, it might be too early to think about art, as everything remains in flux; people are still trapped between temporary housing, reconstruction plans, forced immigration and political maneuvering. But there are indications that art, hand in hand with activism, archaeology and archives, will play a role in the memory and healing work necessary for bringing the city back to life, not as a zombie, but as a combination of present and ghost, moving between past and present. As number of projects such as the Hatay Academy Symphony Orchestra, bringing Levantine music from the region to audiences locally and internationally, the online memory map Beledna Hafıza Haritası, the coverage on the history of minorities in the region at the online platform Nehna, or the heritage archaeology at Tell Atchana demonstrate, the long past and the deep present can come together, healing, recovering, remembering, restoring, all at once.