Iasmin Omar Ata’s graphic novel offers a coming of age story with a fantastical twist, in which Nayra Mansour, a Muslim American girl, is helped on her journey to selfhood by a djinn.

Nayra and Djinn, a graphic novel by Iasmin Omar Ata

Penguin 2023

ISBN 9780593117118

Katie Logan

Introducing a 2018 reprint of Samantha Hunt’s The Seas (2004), the poet Maggie Nelson identifies “a mysterious balancing act between the so-called real and the so-called fantastical, making words like ‘magical realism,’ ‘surrealism,’ allegory,’ or ‘fairytale’ swirl around her work.” Nelson resists these categorizations for the novel, though, describing it instead as “a portrait of human psychology that imagines human emotion as an elemental force on par with air, water, wind, and fire. Seen this way, whatever is not ‘real’ in The Seas could also be read as a deep, perhaps the deepest, sort of realism — a vision akin to, say, the penetrating insight of shamanistic trance.”

Nelson’s assessment of The Seas could just as easily apply to Iasmin Omar Ata’s Nayra and the Djinn. While the text is marketed for ages 10 and up, its designation as young adult literature shouldn’t obscure the seriousness with which Ata treats their characters. In focusing on the complex interior life of young women, the Palestinian American’s newest graphic novel highlights an exuberance that demands a similarly exuberant form, narrative technique or aesthetic. Sometimes, to get to the deepest sort of realism, you need a djinn.

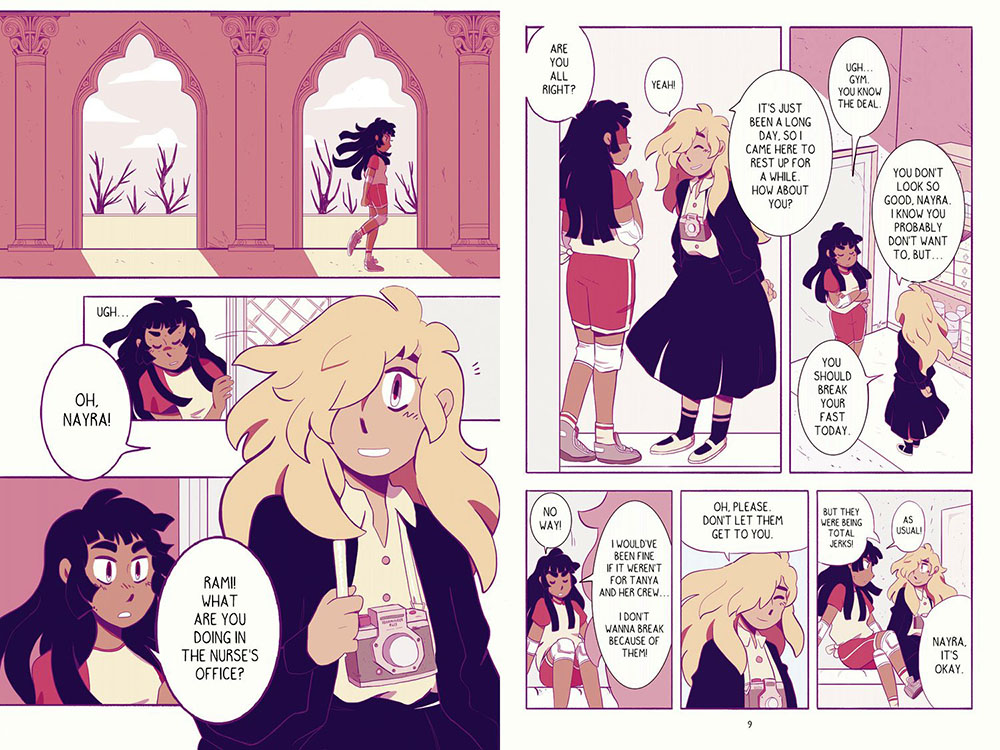

The titular Nayra is a Muslim American teen struggling under the weight of her classmates’ Islamophobic bullying, her parents’ high expectations, and a fraught relationship with her fellow Muslim student, and only friend, Rami. While Rami weathers the turbulence of high school by relying on her friendship with Nayra, the latter draws inward and secretly applies to transfer to another school.

Overwhelmed by feelings and frustrations she can’t quite name, she turns to an online forum for Muslim Americans. Through a strange sequence of events, the forum introduces her to a djinn named Marjan, who persuades Nayra to agree to a pact that allows Marjan to enter the human realm. As the two share more of their worlds with each other, they begin to reckon with the relationships and fears from which they’ve each withdrawn.

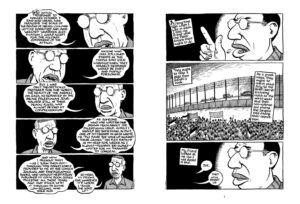

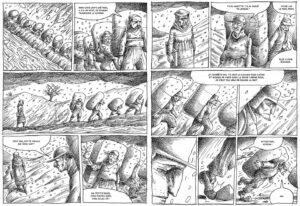

Ata, an illustrator and game designer who also goes by Delta and uses they/them pronouns, possesses a keen eye for making internal tumult apparent to their audiences. Their first full-length graphic narrative, Mis(h)adra, depicts Arab American college student Isaac’s struggles with epilepsy. Using intense contrasting colors, abstract patterns, and surreal chains of knives that bear down on Isaac, Ata creates a powerful visual vocabulary for an underrepresented condition and challenges the dearth of language for representing illness.

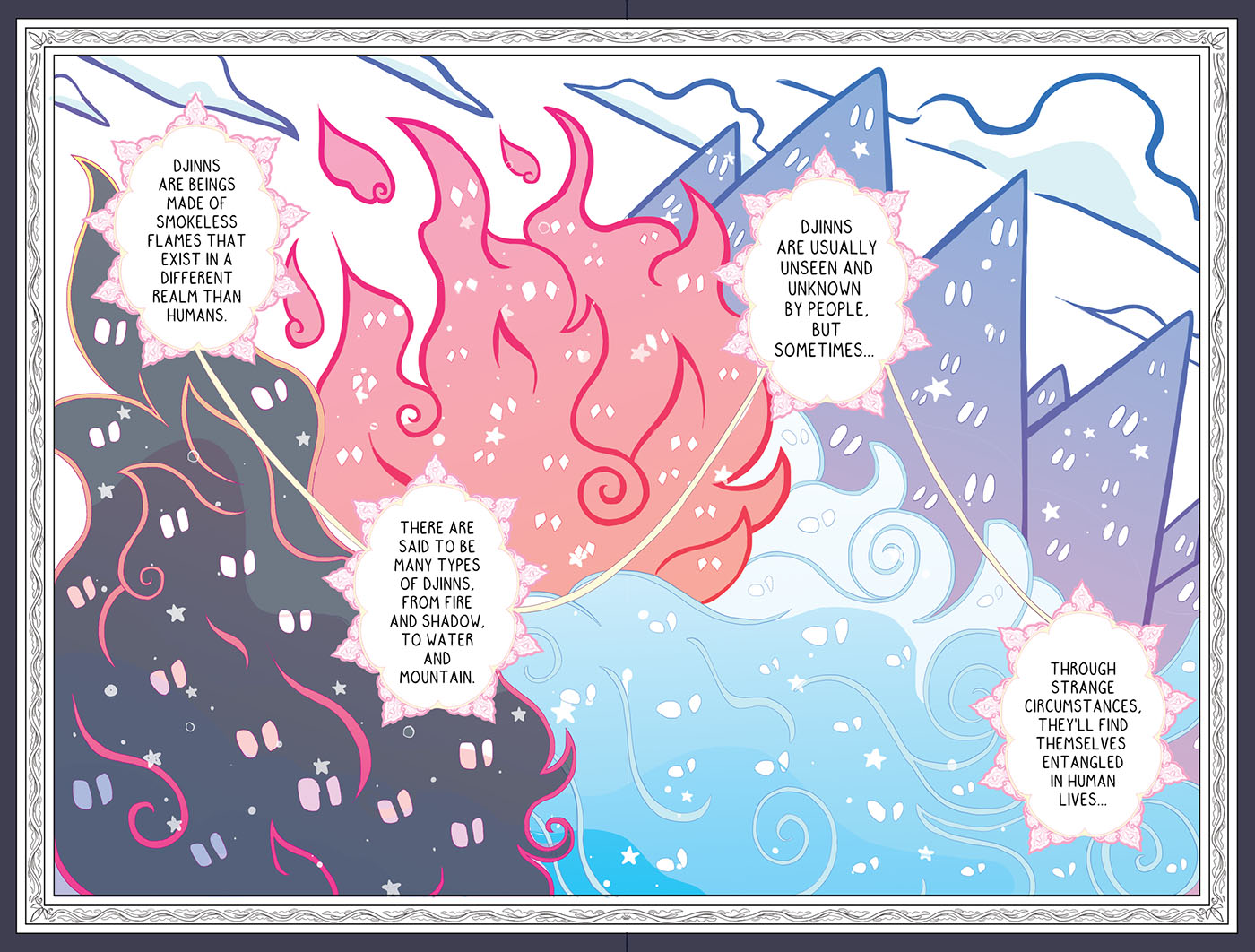

In Nayra and the Djinn, Ata, whose previous work also includes the incisive “The Anti-Palestinian Propaganda You Don’t Know You’re Consuming,” knows that they’re writing for an audience of adolescents and young adults with limited experience of Islam or Islamic folklore. The novel’s introduction includes a brief explainer about djinns, and descriptions of hakawatis and Ramadan — during which the story takes place — that seems directed just as much at readers as at Nayra’s clueless classmates.

Despite the presence of djinns, magical crystals, and portals through realms both fantastic and electronic, the novel ultimately centers the dynamic between Nayra and Rami. Ata conveys the turbulent emotions of a teenage girl for those readers who may have forgotten or never experienced their potency. Feelings of insecurity, anger, frustration, and fear lack expressive outlets and instead ricochet off and through relationships with others. Rami hasn’t done anything to harm Nayra — she’s a supportive if slightly clingy friend — but their friendship is changing nonetheless. The sensitivity with which Ata depicts the shifting contours of Nayra and Rami’s friendship, the palpable “new weirdness between us” that Nayra feels deeply but can’t articulate clearly, places the author among a host of comics creators who have committed to taking the ups and downs of adolescent friendship seriously, particularly for girls, gender non-conforming folks, and queer teens. Nayra and Rami are in good company with the Lumberjanes, summer campers who celebrate “friendship to the max” in the comics of the same name (2014), the Best Friend Squad of Netflix’s She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (2018), and the Marvel juggernaut Ms. Marvel, which crafts a multi-racial, religiously diverse friend group for its young superhero.

As each series highlights, these friendships are affirming and joyous. They are also foundational sites for negotiating and re-negotiating individual and group identity, as She-Ra creator ND Stevenson notes in describing a later season of the show: “What happens when you start to grow in opposite directions? When suddenly there is tension that didn’t use to be there. It’s something I think that happens often in real life that we don’t see often enough in media aimed at girls.”

Stevenson’s question lies at the heart of the conflict between Rami and Nayra, who are growing in ways their friendship might not survive. It can be hardest to stick with the people who remind us of versions of ourselves and of a past we want to escape, and although Nayra doesn’t say so explicitly, it seems clear that Rami now represents many of those things for her. Nayra and the Djinn is attuned to the ways in which the emotional stakes of these seemingly small conflicts can feel massive; Rami perceives betrayal and abandonment in Nayra’s self-isolation.

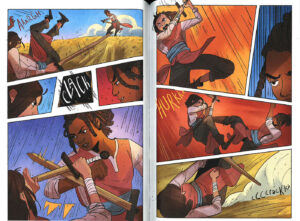

Because of the limits of a teen vocabulary for describing the strength of these feelings and experiences, Ata’s art does much of the narrative’s heavy lifting. The novel’s aesthetics are youthful, filled with pastels and charming details, like the way Nayra’s round eyes transform into stars every time she encounters something thrilling. Light, monochromatic panels offer short flashbacks into the early days of the girls’ friendship. But when characters confront tough emotions, the pastel palette mutates into something more overcast, and shadows and panels uncannily bisect or obscure character’s faces. Nayra doesn’t have to name her fatigue, hunger, or unease for readers to experience them; Ata’s careful penciling and panel construction do that for her.

Even as a visual medium, Nayra and the Djinn is cautious about the role of images, things that can freeze and preserve moments instead of accounting for growth and change. Reflecting on a photo Rami’s taken of the two friends, Nayra says, “I’ve heard that when you look at someone, you see your memories of them — not what’s really in front of your face. Is that why things start to get messed up? Because one day you suddenly realize . . . that those two things aren’t the same anymore.”

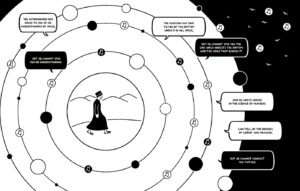

The discrepancy Nayra notices between the image and reality is one the djinn Marjan helps her reconcile. Given the absence of other clear models for negotiating the rocky terrain of intense, formative friendships, Marjan becomes a valuable compatriot for Nayra. Marjan encourages her to adapt her thinking away from either-or logics; as Marjan describe the djinn world, they explain that djinns “live in harmonious communities without separation, gender, or binaries. An individual is only distinguished by the power of their magic.” While Marjan’s description of the djinn world focuses on personal qualities, their dismissal of binaries also affects the text’s temporality. As with Marjan’s adaptive use of the internet, where Nayra’s community of technologically literate Muslim Americans use digital spaces to preserve folklore and storytelling traditions, the sense of what is old and what is new, what belongs to the past or future, blends together. Even page numbers disappear in the sections of the novel that illustrate the djinn world.

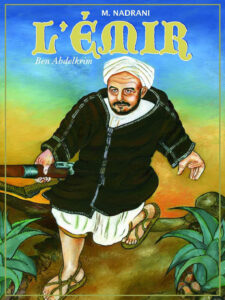

Sherine Hamdy, “Women Comic Artists, from Afghanistan to Morocco”

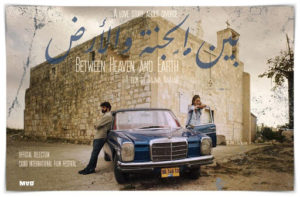

Katie Logan, “Squire, the Provocative Graphic Novel that Channels Edward Said”

Aomar Boum, “Why COMIX? An Emerging Medium of Writing in the Middle East and North Africa”

Marjan and the djinn world are forces that disrupt Nayra’s life, but help her explore notions of trust, power, betrayal, vulnerability, and honesty in new ways. When Nayra wonders aloud whether she’s a good or bad friend, Marjan offer a corrective: “I think you can be both at the same time. And that’s why it can get complicated.” Stepping out of these binaries of good and bad, past and future, “normal” and not is ultimately the thing that helps Nayra start to make sense of her surroundings, to see more complicated patterns, to revise her assessment of certain people and to engage with herself more honestly. And — spoiler alert — it’s the thing that allows her to return to her friendship with Rami by the end of the story. Young readers will find much to cheer for and wonder at in Nayra’s journey, while older ones will be gratified by the care with which Ata weaves the fantastical into the very real.