And the departing caravans

of the tribe of Malik appeared

at dawn like ships

sailing the valley of Dadi

Ali Al-Jamri

The prelude to Tarafa ibn al-Abd’s “Muallaqa,” one of the great “Hanging Odes” of pre-Islamic Arabia, is so typically Bahraini that I have to smile whenever I read it. In the third line of the poem, the desert caravans are like ships and the valley is likened to a sea. The fourth line references ‘Adawl, then a ship-building town in the Greater Bahrain region. The fifth line conjures a picture of this caravan only a seafarer could paint: Its forepeak / parts the water as it pushes forth / like a child’s hand plowing / through soil. In the sixth line, he describes his beloved Khawla, whose slender neck is adorned with strings of chrysolite and pearls.

There are the sailing metaphors. There are the specific place names. There is even a pearl necklace. Our 6th century poet does not dwell on these images very long — in fact, most of the poem is a passionately detailed description of his camel — but in the brief introduction, he makes sure you know that a Bahraini has authored this poem.

These flourishes are so very typical. Between Two Islands, an anthology of Bahraini-British poetry that I edited, begins with these lines by Taher Adel: A reincarnated pearl diver / diving headfirst into ancestral seas / finding pearls that resemble faces. My own written drafts are similarly awash with metaphors of pearls, divers, springs and dhows. I recognize that proud signature in Tarafa’s work because I’ve signed it myself. Trademarked Bahraini, we want to say, our sea’s got pearls.

Yes, the sea is ever-present in Bahrain’s idiomatic language. I discovered my favorite in the 18th century biographical dictionary The Pearls of Bahrain, by Yusuf Al-Bahrani, in which one early-modern scholar is titled the diver of the sea of knowledge. Let us dive into those seas now.

•

The link between Bahrain and the sea goes much farther back than Tarafa. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero’s search for immortality takes him on a sea voyage to a distant land where his immortal, antediluvian ancestor waits. When this ancestor (variously named Utanapishtim, Atrahasis, and Ziusudra) dashes his dreams of eternal life, he offers Gilgamesh a consolation prize: in the Abzu, the sea-beneath-the-sea, is a plant that can return one’s youth.

No sooner had Gilgamesh heard this,

He opened a shaft, threw away his tools,

He tied heavy stones to his feet,

They pulled him down into the watery depths

He took hold of the plant and pulled it up, it pricked his hand

He cut the heavy stones from his feet,

The sea cast him up on its shore.

This plant is soon stolen by a snake, to Gilgamesh’s dismay, but it is no coincidence that the legendary king uses techniques evoking the Gulf’s pearl divers to reach the sea’s depths. The Abzu in Sumerian mythology represents the freshwater aquifers which Bahrain is thought to be named after. The Two Seas in Bahrain’s name are the rich freshwater wells that spout beneath the saltwater sea. These springs spout in countless spots in Bahrain, both on the land and along its seabeds. They are the reason for the island’s richly fertile soils and the enabler of the Gulf’s seafarers, who once depended on knowledge of these freshwater deposits hiding in the sea to supply their drinking water.

Enki was a Sumerian god associated with the Abzu and worshipped in Dilmun – that is, ancient Bahrain. And Dilmun, to the Sumerians, was seen as the land of eternal life and plenty. No person grew sick, old or hungry in Dilmun. As one Sumerian poem tells us:

Dilmun, land of the pure

Where no crows caw

Where no lions roar

Where none grow old

May Dilmun be a port

Where all the world will call

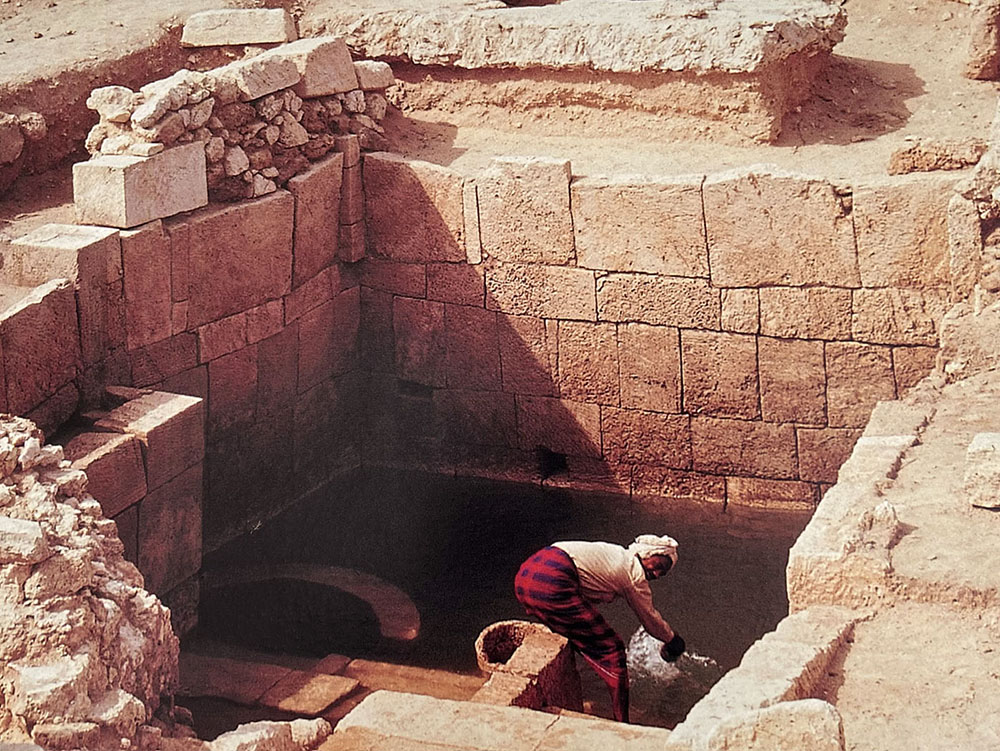

Overlooking the sea from a hill and situated atop an abundant spring, the Temple of Barbar was built on Bahrain’s north coast and dedicated to the worship of Enki. Five thousand years old, its site is the meeting place of sea, spring, and civilization. Here, worshipers ritually cleansed themselves in the spring. Here, sacrifices were made to Enki. Here, dates were pressed into wines of holy vintage.

Perhaps it is not right to accuse nature of abandoning the place. Perhaps it is we who expelled nature.

The Temple of Barbar is thrice-abandoned. It was first abandoned by the people of Dilmun who, after at least a thousand years of continuous use (the oldest building dates to 3000 BCE, the most recent to 2000 BCE), left it to vanish, possibly due to changes in their religious or political circumstances. The site lay dormant for millennia and was rediscovered by archaeologists in the 1950s.

Now it has been abandoned again.

When I visited the site recently, a bored guard watched over the only entrance. A low fence marked its boundaries. The small visitor center, little more than a glossy portacabin, was thrown together in the hope of attracting national and UNESCO interest. There is a picture of the Danish archaeologists who led the excavations smoking pipes and wearing ghutras, and another of the crowds of local villagers hired to do the real work of digging. Yet another picture shows the great bull’s head, the religious icon displayed proudly in the national museum and the best-known symbol of Dilmun’s civilization. One color photograph shows a man ankle-deep in the spring, which was still flush with life in the 1950s, five thousand years after our ancestors first lined it with limestone walls and built their temple complex. But after the bout of activity that threw this little visitor center up, the Ministry of Culture’s attentions shifted its attention to projects more glamorous than an old temple in an old village.

The third abandonment is by nature. The hill has disappeared; the land leveled over the millennia. The sea cannot be seen, heard, or smelled, and reclamation projects are remaking the coast so that it lies farther north. The spring, which gushed forcefully for millennia, has been dry for several decades. Perhaps it is not right to accuse nature of abandoning the place. Perhaps it is we who expelled nature.

Absence thickens in Barbar’s still air.

Malchiyya’s beach is still beautiful. The sea laps playfully at the sands. It stretches out from Malchiyya village which, unlike Barbar in the rural heartlands, neighbors a royal palace as well as the kinds of neighbors that palaces attract. It is one of Bahrain’s few remaining public beaches — most belong to hotels, companies, and private individuals. Malchiyya is situated on the island’s west coast, and on a clear day one can make out the Arabian mainland in the distance.

The people of Malchiyya claim Tarafa as their own. He was from the Malik tribe, and Malchiyya — the vernacular pronunciation of Malikiyya — was one of the tribe’s homes. Some 1,500 years ago, a young Tarafa may have sat at this same beach composing poetry about caravans like ships and valleys like seas.

Of course, it would not really have been the same beach, nor the same sea. The nature Tarafa knew was unlike today’s in two key details: the land’s contours and the sea’s health.

Neoliberalism demands unlimited growth. In Bahrain, that has become a desire to grow the land beyond its natural limits. The islands are already one of the most densely populated places in the world. In 1941, the first census year, the island population was just 90,000; today, it is over 1.5 million. These islands have a landmass of 786.5 km2. A significant proportion of that landmass is uninhabited desert — those life-giving freshwater springs are concentrated along the northern quadrant of Bahrain, and its inhabitants have long congregated around them. The entire country is smaller than many major cities — Riyadh, 2,000 km2; Cairo, 1,200 km2; London 1,600 km2; New York, 1,200 km2. And Bahrain, unlike those cities, has virtually no hinterland on which to draw for food, water, and materials.

Over the past 50 years, the neoliberal addiction to ever-ascending annual GDP figures has pushed Bahrain’s natural reserves to the brink. The land was the first to go. Villages and towns were expanded substantially. The farmlands my grandfather worked and played in as a child of the 1930s became the neighborhood where he raised his family in the 1970s. Incrementally, the “Land of a Million Palm Trees” became the “Land of a Million Villas.” But nothing disrupted the water aquifers — the Abzu — more than the drilling for oil. Once, hundreds of man-made irrigation channels criss-crossed the land and watered countless date groves and orchards. My mother can remember playing in these in the late ’60s, and the largest were nicknamed rivers. Yet I struggle to imagine them. When the ‘Ayn Adhari spring – one of the largest in the country – dried up, a swimming pool was constructed there instead.

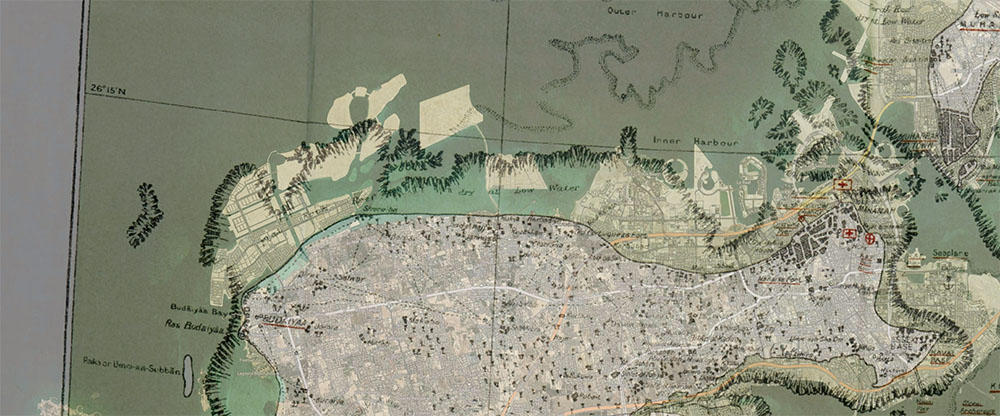

With most of the land used up by the end of the 20th century, Bahrain turned towards the sea. Bahrain had reclaimed small parcels of land for decades, but the turn of the century saw the pivot towards mega projects. First came the Financial Harbour, with all the ugly grandeur of pre-Crash skyscrapers. Then came vanities like Amwaj Islands, with their silken promises of a glamorous lifestyle. Lately, projects have included the North City, which houses a new generation of Bahrainis where their sea once was. Land reclamation is a misnomer: how are we “reclaiming” from the sea that which never belonged to any of us? The north coast that Barbar’s temple once overlooked has been completely transformed. There are now virtually no natural coastlines left on Muharraq or Sitra, the second and third largest islands of Bahrain.

Every time I visit Bahrain from Britain, it has changed again. I remember the first time I had the misfortune of visiting Amwaj Islands in 2014. These islands have pipe-fed gardens, broadways to walk down, and restaurants to feast in. After we lunched at one such restaurant, we walked along the seafront. I leaned over the railing. Below this cancerously beautiful island were the corpses of some dozen fish floating listlessly.

In the heart of Sitra lies Sheikh Ahmed bin Sa’ada’s tomb. It is located in a parched graveyard, though young trees planted by loving caretakers provide some shade still. To reach it, we had to park some distance away and walk past the memorials of Sitra’s sons killed by police. This is the old Sitra, which remembers armies that slaughtered them and leaders that failed them. Even 200 years ago is recent memory to this land.

Like Gilgamesh, I am visiting an ancestor from a bygone age. Sheikh Ahmed lived in the 13th century and was one of Bahrain’s great scholars of the medieval period. He corresponded with Rumi and was contemporary to that other great rationalist scholar, Sheikh Maytham Al-Bahrani, whose own shrine stands grandly in his home village of Mahooz. But this tomb is a miserable little building. When we entered it, a single air conditioner blew silently from its place above crumbling plaster that revealed bullet wounds in the wall.

Sitra’s name translates to “jacket.” When Sheikh Ahmed was buried here, on the island of his birth, it would have been jacketed by its thick forests of palm trees. We catch a glimpse of Sheikh Ahmed’s island in this early 19th century poem by Abduljalil Al-Tabataba’i, whose words channel the more ancient “Dilmun, land of the pure”:

By the grace of God, we were borne by the sea

to anchor our ships at this fine harbor.

Like a curtain drawn back, like a veil raised up

we rushed ahead to the shores of Sitra.

The palm trees rain a great harvest of dates

divine delights, like Eden’s nectar.

Her springs of freshwater gurgle and spurt

in wilderness and waters, they flourish and burst.

Today, a visitor might be forgiven to miss the fact that Sitra is its own island. The land reclamation between Sitra and Bahrain has been so extensive that only a small channel separates the islands now. Extensive projects are pushing Sitra’s landmass eastwards into the sea, doubling the island’s size. They may also be forgiven if they fail to see the island’s beauty. Much of the island is now industrial. The air is polluted. There are virtually no trees. Sitra is naked and bare and riddled with bullet holes.

I was made foreign from my land. Political repression in the 1980s forced my parents to build their lives in the West, where I was born. We returned to Bahrain only following some reforms in 2001 (as to the endurance of those reforms, one may refer to the bullets in Sheikh Ahmed’s tomb as a symbolic indicator). Growing up in London, I was enamored of the image of Bahrain as an oasis in the sea. A prose poem of mine in Zindabad Zine explores the disappointments encountered on our return to this promised land:

“All this was palm trees in my day,” my Baba would say, overlooking Bani Jamra from the hill where Mulla Yusuf’s house once stood. Our sight stretches from the pockmarked graveyard to the paved-over farms, where dust rinses the sun-bleached walls of a modern villa with garage space for three cars.

I never saw the verdant Bahrain. Truthfully, I wouldn’t have seen it had I been born there, as the desertifying economic processes began before my time. Because I had to imagine Bahrain before I saw it, two lands exist in my head: the real one I know and touch and experience, and the spiritual one I can access only through literature and oral histories.

Land is profitable, so what do you do when you run out of land? In Bahrain, you create more: www.mapbh.org is a project inspired by Visualizing Palestine. The Google Earth technology that enables it was originally banned in Bahrain, as it had exposed the extent of the lands held by a private minority. By transposing older hand-drawn maps onto modern satellite imagery, we can see with grim immediacy the devastation wreaked upon the coastline. With a click of a few buttons and sliders, we can easily compare the transformation of Bahrain. A 1937 map outlines the shallows, which look like an aura surrounding the island. With a semi-transparent overlay, we can see that today’s land reclamation across the north coast, Muharraq, and Sitra fill in the space between the original coastline and that aura.

In 2021, plans went public for a new city comprising multiple new islands connected with bridges. If the plans go ahead, Bahrain’s landmass will expand by some 100 km2 — enlarging the country by 12%. These new islands would be built near Sitra, spreading east and further east again. In 2023, the plans have begun to create extreme fears and outcry from Bahrainis as policies began to pass through Bahrain’s parliament for rubber stamping, to pave the way for construction.

The thing is that the sea is truly Bahrain’s commons, and has been for millennia. It belongs to everyone and no one. Land reclamation is sea privatization. And the other issue is that the sea is already inhabited: the “Great Shoals Region,” as the plans dub it, would be built precisely there: atop the largest region of shoals in the local sea. The Great Shoals is a huge section of sea and one of the most important marine breeding grounds. If the Great Shoals are destroyed, Bahrain’s fish will disappear.

I’ve dwelled on the sea and the springs for us land mammals of Bahrain. But the fish are as much a part of this land as we are, and Bahrain’s folk poets have long held them in esteem, considering them brethren. They’re as much a source of inspiration for Bahrainis as the waters they inhabit. By example, one early-modern era poem, “The Tale of the Fish,” by Hassan Al-Malili, regales us with a war between the halal and the haram fish. When a catfish kills a Hamoor (grouper, one of the Gulf’s largest and most esteemed fish), the halal fish declare the Chan’ad (mackerel) their prince. They gather all the halal fish, even the small Safi (rainbow fish) and fight back. But my favorite fish-related poem is a tongue-in-cheek fisherman’s pastiche of the revolutionary poem “The Desire of Life” (Iradat al-Hayat), by Abu’l Qassem Al-Shabbi:

One day, when Seabream Spring acts on life’s desire,

It shall force the motion of the Sea’s power,

Thus shall it be: Sardines shall scatter,

And Dolphins? Dolphins shall vanish forever!

For they who do not thirst for the corals

Trip on their tiled floors, perish, expire.

So said the Safi in their countless schools,

So said their flesh, their oils, their pure matter.

The Subayti, Gargafan and even the Sals

Raised their voices from their usual murmur…

Seabream Spring is a freshwater spring famed amongst older generations and increasingly forgotten by younger ones. And “sha’am” (seabream) is only one letter off from “sha’ab” (people). Perhaps a clumsy error in reciting the opening line led to this poem’s good-humored invention. For the fishermen who spun this poem, it was no doubt a fun bit of wordplay to pass the days spent out at sea. But I struggle not to see today’s troubles written into it. Should the spring reject the sea, the sea will be left barren: it’s right there for us to see, written like a prophecy.

Today, many in Bahrain are filled with anxiety. We are increasingly shamed by privatized beaches and a devastated sea. Of course, those most anxious are also those most affected and least involved in this destructive decision-making.

How will the people of the Great Shoals Region be fed? To build on the Great Shoals would destroy Bahrain’s fish stocks irrevocably. The aquifers are already depleted, so where would fresh water come from? Where would waste be pumped?

The plans for this city will no doubt make a few government officials and development companies fabulously wealthy. Parcels of land will be bought, built on, sold, built on, sold, and so forth. Eventually, a family may buy a house there at a high price and hope that the value does not plummet. But however much they pay, the real cost is incalculable.

Tarafa uses the prologue to his Muallaqa to transform valleys and dunes into a sea. He makes ships out of caravans and loads his lover down with pearls. While I recognize the Bahraini in him despite the centuries, I wonder if he would recognize the Bahraini of today. As a nation, Bahrain is doing the reverse of Tarafa: we are turning the sea into desert. When the physical features that defined us since the time of Dilmun are gone, what is left of us? How can we read our forebears’ love of the sea and not be filled with shame?

It is a vision which leaves me sleepless. What will the future hold for us? To that, I do the only thing I can do – pick up my pen, write a poem, and imagine the future.

Iftar at the Great Shoals City, 2123

Kneading dough from dust,

mother bakes our Iftar bread.

We’re off to watch the prime-time show:

the Great Shoals City.

You see, without the electronics

Grandma tells of in her tales

and without the Ramadan serials

she recounts like episodes of Kalila wa Dimna,

we watch the emptied city crumble

and make our playful bets:

this residential tower or that mall?

Every evening, we play this game

to forget hunger and thirst.

By my side kneels my strange uncle.

Palms open, he recites the names of fish:

Safi, Chan’ad and Hamoor

Um Ar-Rubyan and Abu Salbukh,

Baaliq and Baalul,

Jamjaam and Khaakhun,

The Captain’s Donkey,

The Bride’s Brush,

Safi, Chan’ad and Hamoor

He repeats these dimly-learned words

as if his head was bowed beneath the schoolmaster’s cane

— then mother shouts down his horrible voice.

Bit by bit…

Pane by pane…

Pillar by pillar…

The empty city crumbles into the empty sea,

and tonight, it is the residence that collapses.

I eat my prize: a date as big as a grape.

Grandma tells of the plump dates of her childhood.

My uncle quietly finishes his prayer and prostrates.

The city’s silence mourns the fallen tower.

Behind us, the sun snuffs her lantern.

Hunger raises his voice.

The deaf sea licks at the barren city.

Notes

“Tarafa’s Hanging Ode,” translated by Huda Fakhreddine (2020)

The Epic of Gilgamesh, translated by Benjamin Foster (2019)

All other translations my own.

بارك الله فيك يا شاعر البحرين علي الجمري.. شرح رائع عن البحرين.. أخذتنا في رحلة جميلة بين الماضي والحاضر.. وأنا بحرانية ولا زلت أتذكر البحرين الخضراء في سبعينيات القرن العشرين وامتداد البحر قبل أن تداهمه الرمال التي دفنته وقلصته حتى لا نكاد نراه.. ولا يوجد شواطئ الآن إلا القليل جدا ولا تكاد تصلح للسباحة.. وإذا أردت أن تستمتع بالمشي على ساحل وجب عليك استئجار ڤيللا فندقية تطل على البحر وليس الجميع يستطيع ذلك.. للأسف.. أحسنت الطرح وقد أعجبني مداخلاتك الشعرية لوصف حالات التغيير التي صارت على بلدي الحبيب البحربن..

May God bless you, Bahraini poet, Ali Al Jamri. A wonderful explanation about Bahrain. It took us on a beautiful journey between the past and the present. I am Bahraini and I still remember the green Bahrain in the seventies of the 20th century and the expanse of the sea before the sands that buried it and shrunk it so that we can hardly see it. There are very few beaches now, and they are hardly suitable for swimming, and if you want to enjoy walking on the coast, you must rent a hotel villa overlooking the sea, and not everyone can do that, unfortunately. You did a good presentation, and I liked your poetic interventions to describe the states of change that have taken place on my beloved Bahrain.

Thank you for writing this, it was a beautifully put together piece, it is appreciated.