Aïda Nosrat is a multi-talented performing artist from Tehran who is making her way in the west, while supporting the women and freedom fighters in Iran. She spoke to TMR's editor-in-chief during the 19th annual Festival Arabesques, in Montpellier.

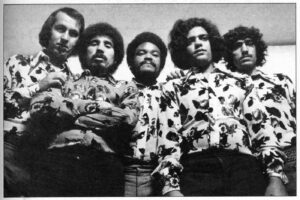

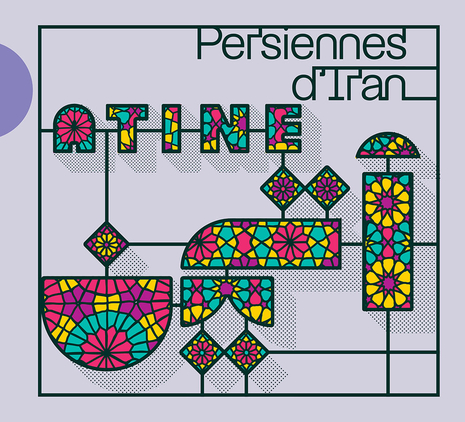

Aïda Nosrat and the other four members of her Atine quintet — Sogol Mirzaei on tar, Christine Zayed on qanun, Marie-Suzanne De Loye on viola da gamba, and Saghar Khadem on Persian percussions (tombak and daf) — are consummate players. They bring incredible energy and passion to a repertoire of original, poetry-influenced compositions. Atine left me nearly breathless when I had the pleasure of catching them at a recent concert at Montpellier’s opera house, where they performed as featured artists in the 19th annual Festival Arabesques.

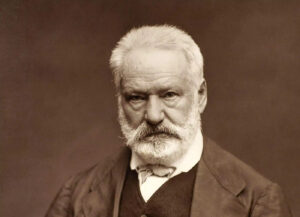

Aïda Nosrat is a Tehran-raised, Paris-based vocalist, composer and former violinist with the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra. She emigrated to France in 2015 with her then-husband, guitarist Babak Amir Mobasher, and they soon became fixtures at Paris’ Cité International des Arts, and later, the Atelier des Artistes en Exil. Their joint album, Manushan (derived from The Shahnameh or Book of Kings, by classical poet Ferdowsi), was partially recorded in Tehran and Paris, and released in Europe and the US. Manushan fuses Persian music with elements of jazz and flamenco.

Nosrat’s more recent recording is her breakout album with Atine, Persiennes d’Iran. It features songs and instrumentals influenced by Rumi (b. 1207), but also other classical Sufi poets such as Saadi (b. 1184) and Sheikh Bahāʾi (b. 1547). The songs Atine presented in the Festival Arabesque were predominantly warm and imbued with color, melancholic here and there, yet unexpectedly energizing, which is not always the case with traditional Persian music. One sat up to listen even more intently during the solos by Saghar Khadem, Sogol Mizraei and especially Christine Zayed on qanun, who is the group’s sole Arab musician. A Palestinian raised between Ramallah and Jerusalem, Zayed’s innate relationship with microtones made her contribution to Atine seem effortless.

In the live encounter, one sensed Aïda Nosrat’s soulful devotion to the music, and her contralto register lent a sort of atavistic authenticity to the songs, almost as if she could be singing them 1,000 years earlier, during the era of the Sufi poets she professes to love.

TMR Artist at Work Interview

Why would a 40-something Iranian woman in 2024 be enamored with poets who were alive 500 to 1,000 years ago?

Aïda Nosrat: There are two aspects to this. The first is that poems from any of these Iranian poets, when they get translated, don’t transmit the essence of the poem, which when you read it in Persian, is something else. But … [then] you can translate it for yourself. When they speak about love, it’s a love that I know most people know, a love between humans, a kind of mystic love. I believe that humankind is so far away from that love, yet we long for it. And it is a mystic love, because when you dig deep, it has layers, and emotional levels, and the closest I can describe it is that mystic love is akin to the love between parents and their child, because parents never ask anything from their child. They just love them unconditionally.

My point of view is that mystic love, the love the universe has for us, gives and gives and gives, like the sun.

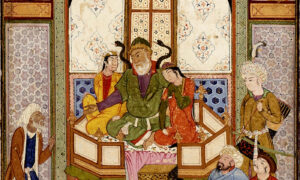

And that’s why the sun is a symbol of love in Iranian mysticism, and in what we sometimes call the religion of love, or mehr, because the sun is always giving and not asking for anything in return. So this is one aspect, and the other aspect is that most of these poets were Sufi mystics. They reached a level of human consciousness and human love that they couldn’t transmit with normal words. So they started to write poetry, and that’s why, 800 to 1000 years after creating these poems, they are still new. They still have deep messages to convey to humanity, because we are not yet there. We are still so far from the level of consciousness they strived to attain. In my opinion, this is why [their words are] still new and still have so much to teach us.

Another sort of innocent question is, why do you suppose Iranian culture, particularly in music and film, is often so melancholic, and sometimes sad?

Aïda Nosrat: When you read Iranian history, Iran was under attack for most of our history because of the geographic situation in the middle of the Middle East. Iran is a crossroads, a way to reach the oceanways to the south for so many countries, like Russia. We were often under attack. I imagine this brings a certain amount of sadness, and it could be genetic. Also there is this feeling of separation that the poetry relates as well. Because in these mystic poems, beside love, there is also melancholy and sadness from the separation from the source, from the Creator. You know, cultural events in Iran … and the philosophy, the deep philosophy of Sufism and consciousness … happened over the centuries. So are we somehow melancholic people. It’s also the story of being exiled, and it’s not something new. I mean, Rumi himself was exiled from Iran because the situation was similar to the one we find ourselves in, different at that time, on the surface, but deep down, it was the same story, the same condition as today.

You’ve said you’re not sure about returning to Iran. Do you sometimes feel that you’re an artist in exile?

Aïda Nosrat: I can’t go back.I don’t know what [would] happen to me. In Iran, I was not political; I wasn’t an obvious troublemaker. You know, with our album Manushan, we had to be discreet, we couldn’t do any publicity or social media for it, because I was afraid the secret police would call and iterrogate me — why are you singing? Why are you doing? … blah, blah, blah … which happened to many of my friends. I didn’t want to get involved in [protest at home] but at the same time, I realized that I couldn’t build my career in Tehran, because it takes lots and lots of energy and effort and money to make an album. Then you cannot even do publicity for it, or have public concerts for it.

Now that you’ve given up on a music career in Iran and you don’t have to answer to the Iranian authorities about creating music or singing, do you feel free?

Aïda Nosrat: Yes. As soon as I got out of Iran, I started to free myself, and I haven’t stopped talking about the situation of women… I’ve been active the last two years in the Woman Life Freedom revolution in Iran. When it started I was devastated. I mean it was so painful, the daily events were horrifying. I’m sure that it wasn’t just me, but all Iranians who are living in and outside of Iran. We were the same somehow, every morning. Waking up, the first thing I would do is grab my phone and see what was going on in Iran, crying, and would get ready to face my day. It was weird because you felt lots of emotional pressure; I had to put on a mask to deal with my life here. Many people in France, in Paris, didn’t even have a clue about what was going on in Iran. So, yes, it was very difficult and really painful.

Generally, what I believe in is slow change. I don’t believe in sudden revolutionary changes, because sudden revolutionary changes will always be destructive, and we already experienced it 40 years ago with the revolution in Iran.

Can you talk a bit about your work on the album From Kabul to Bamako, that you did with Sowal Diabi?

Aïda Nosrat: I sang on that recording and I even composed a song, “Beshna as ne ek le nay,” derived from a very famous Rumi poem. If you listen to the whole album, “Kara Kara” became the hit of the album, because the main team is from Mali. Mama Niketa, who I sang with, is a Malian singer. We mixed Malian music with Kurdish music and Afghan music. It was actually a big success here.

What are your hopes for Atine?

Aïda Nosrat: I hope that we make another album. I really hope that this project continues.

How did Christine Zayed, the Palestinian qanun player, get involved with your group? I ask because you don’t often hear about Iranians and Arabs working together, playing together (although I know that musicians typically have no boundaries and there has always been a lot of crossover) …

Aïda Nosrat: It’s interesting because many Iranians have this memory of what we learned about our history, and feelings about Arab countries and Arab people, because they attacked Iran 1400 years ago and imposed their religion on us.

Because before that you were almost all Zoroastrians.

Aïda Nosrat: Exactly. And they forced Iranians to speak Arabic. If it weren’t for Ferdowsi and this one king whose name I don’t remember — Ferdowsi kept the Persian language alive with The Shahnameh, The Book of Kings. Without these two people, we would have lost our language … So [this wariness toward Arabs] is kind of carved into Iranian DNA, and collective memory, collective consciousness, but it happened long ago. That is a long time to keep the hatred inside yourself. But until I came to France and made Arab friends here, I never had Arab friends in Iran and I didn’t feel very good about Arab people. It was transmitted to me, generation by generation, from my father, from his father to him. Things changed for me when I visited Morocco, when I went to Tunisia, and found that we have so many things in common.

How did you bring in Christine? Zayed?

Aïda Nosrat: Five years ago we performed in the Mawazine Festival in Morocco; our producer had a very good relationship with Morocco and this festival. He asked us if we wanted to participate. It was me and Sogol Mirzaei, the tar player. Sogol brought in Saghar Khadem, the percussionist, but we needed another instrument. And then Sogol somehow found Christine, who was living in Paris. The repertoire was absolutely 100% Persian traditional repertoire, mostly with rhythms which are suited for dancing. It was then and there that our producer proposed that we put together an all-women band, make a girl band … We said, why not? It was a very interesting proposal. And then we searched for Marie-Suzanne. We were looking for a cello player, actually. We tried with two cellists, and it wasn’t what we wanted. And then Sogol found Marie-Suzanne, and when we played with her, especially with the gamba which has these movable frets that also we have in Persian instruments, that enable us to change the mode, or change the microtones. Her viola has seven strings, so the bass and everything about it was absolutely great for our project.

The last thing I wanted to ask you about is your background as a violinist. How did that evolve into the career you have now; do you primarily see yourself as a vocal artist?

Aïda Nosrat: I see myself as a free-spirited musician, and these are my tools. My voice is a tool. My violin also is a tool. I play piano as well, a little bit of mandolin, I play some guitar. My first instruments were flute, and recorder. I compose music as well. So these are my tools to express myself musically. Mostly, I’m more comfortable with my voice because I feel freer. I can do whatever I want. I mean, not necessarily in the type of music that you heard in Montpellier, because that’s like classical music where you have to follow specific rules. But when I create my own music, it’s totally free. When I improvised during the Montpellier show, I improvised in the context of Iranian traditional music. But when I improvise for myself, for my music, it’s totally free. I use Iranian techniques, and I mix it with with jazz music, I mix it with flamenco. I mix all the time.

How does one go from performing for seven years in the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra to being a free-spirited world music performer and composer? That seems like a leap.

Aïda Nosrat: I don’t know. This is something inside me, my spirit is like this, even when I cook. I can cook perfectly traditional Iranian dishes, but I also improvise cooking, you know, different techniques … I align with different cultures. I’m like water, you know? Whenever I visit other countries, I mix with their culture. I would say I’m very much a resident of planet Earth. I mean, my heart is in Iran, of course, because I spent most of my life there. But at the same time, I wanted to see the world, see new people, experience new cultures, and exchange cultures with people. Music is very fluent; it’s also like water. Music has no borders. It is itself a language. I feel like I can communicate with anyone, without any exchange of words with other musicians from totally other cultures and countries, just playing music together.

With respect to my classical music background, I’m very grateful that I have this strong base and training in classical occidental music. When I was a child, I also trained using my voice in classical or traditional Iranian music. But I was always passionate about learning other cultures and other musical traditions. I grew up in a family in which my father listened all the time to these old songs from the ‘60s and ‘70s, and at the same time, Azeri traditional music, and some Iranian jazz music, as well as rock, the Beatles. My father is also an artist. He’s a painter. So I grew up in this atmosphere in Iran. It was a multicultural atmosphere. Even though we were in Iran and it was kind of difficult to have free interpretation with the outside world. It’s my passion to mix cultures.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)