On an island in the Mediterranean, a biologist tracks an elusive salamander, which she has never seen except in artists’ renditions and her own dreams but which they say is native to the area.

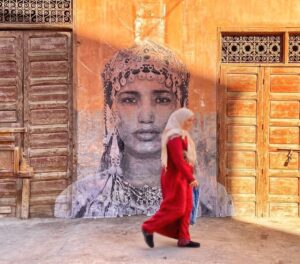

Sarah AlKahly-Mills

Zahra

In only a day’s time, Zahra will find herself swimming across a sea, and the gruelling journey will be infinitely preferable to what she will leave behind. Anything, anything at all to escape. She will formulate her plan, if flinging oneself headfirst into the Mediterranean with nary a belonging but a good luck charm may be called such, in between blows from Kareem, the generous. For now, she sits in a café in Bsharre with the old woman they call Humbaba on account of her obsession with guarding the last cedar tree, and they wait for their coffee to arrive.

“They want to put me in a ‘home,’” Humbaba says of her adult children. She refuses to budge. A sentinel does not give up her post. “If they call that a ‘home,’ then what is a prison?”

Zahra looks across the way to an ancient limestone house, its red tile roof missing shingles like a grin its front teeth, its walls enclosed with something like a police perimeter. Traditional Lebanese house! reads a sign with an arrow pointing to the crumbling edifice, designating its purpose as an attraction for the tragedy tourists who flock to see the ruins.

“Tell me the story of Warda,” Zahra implores.

“Warda, ya Warda. Warda was born before the Blasts, before even the Wars! A long time ago, fi qadim al-zaman, when you could eat pine nuts and drink from the streams of the Qadisha Valley and buy things you didn’t need!”

When she talks about the Golden Age, Humbaba’s cloudy eyes smoulder with dignified, martyrish resignation. She scrapes mindlessly at dry scales on her hands. Her short white hair branches out in peaks and slopes like thorns. She puts Zahra in mind of a mother she never knew.

“She picked wild berries, chased down kibbeh nayyeh with arak, listened to vinyl records of Fairuz, wore full skirts and sunglasses, drove her own Beetle, and her purse was never empty of Lucky Strikes!”

“Yes, Humbaba, but tell me the part when she kills her husband,” Zahra says.

Humbaba looks behind her to the etiolated cedar. Coffee arrives at the hands of a handsome waiter. A tourist snaps two photographs: one of the house and one of them.

Zahra hitches a furtive ride back to Beirut on a small bus overflowing with bodies. Warda, she says to herself like a spell, and it snaps its fingers — gone! The sounds of snorting, wheezing, cursing; the smells of exhaust, sweat, chemical aftermaths, brine. She grips the ladder with one hand and stretches the other out into the wind, leaning with the bus as it slides like a puck down its winding road, smiling, feeling as though something grand were on the brink of birth. She knows the story more intimately than the sound of Kareem’s weight as he steps on that loose tile between kitchen and living room. She became enamored with Warda immediately after Humbaba told her the woman’s story, which was after Kareem had let loose his German Shepherd, Zelda, on her black cat. She had named him Najmi for his coat, dark as a star-studded city night after the grid collapsed, but Kareem had named him Haram because whenever he would bully the creature with a stomp of his foot and laughter that barked like his hound, Zahra would say, Haram! Mish haram? Isn’t it a sin to torment an innocent creature? All that had remained of the innocent creature was gore, a memory she painted over with vermillion thoughts of revenge set to Kareem’s words: Such is nature.

It is only Warda she sees now, standing over her felled husband, engorged a translucent pop-ready purple with a poisoned morsel caught in his throat. He died the way he lived, swollen with greed. Zahra laughs with self-pity. The humid air leeches the last of the spell’s bliss from her mind. Where would I even get poison?

Home is a stilt house near Ground Zero, one of several spread out over the seawater that rose like a prophecy and washed away the Mövenpick Hotel, many cafes and restaurants, and the last of a generation. She pays the taxi boat driver with a promise and takes measured steps along a creaky boardwalk with handrails made of rope. He waits where the water laps at a stilt.

“I need to pay the taxi,” she says to an empty home. “Kareem?”

The house rocks and shifts with the waves. The search lights of foreign government vessels on the lookout for people-smugglers illuminate the dark living room at intervals, landing on wet eyes that glow a ghoulish green. Zelda guards Kareem’s stash: wads of worthless cash, bags upon bags of salaam, and all the scraps he’s collected from those desperate for the hallucinogen, bartering away the last of their valuables in exchange for a moment of peace. A moment of salaam. She’s never tried the drug, but they say it makes a person rise far above their body into the sky and meet their idea of home.

Nothing leaves or enters the cage where Zelda and her master’s cache are kept, not without his knowledge. A gleam at the edge of the enclosure catches her eye. Within her reach, a piece of green porcelain shaped like a hook, something that looks as though it were broken off a larger body. Zelda snarls as Zahra extends her hand slowly and snatches it away quickly, pocketing the piece before hearing the loose tile move.

“Stealing from me, ya kalbe?”

A search light finds Kareem and lingers on him, and Zahra, dread be damned, plucks a moment of wicked pleasure from the knowledge that nothing but his deception and her despair could have ever bound them together, so undesirable he was by each and every metric. He had had to lie his way into her, a woman made pliable by all the dead ends she’d rammed her panicked beak into. Cracks in his façade had begun to show not a moment after he’d no longer had any reason to pretend, and he had steadily decayed over the years, chain-and-padlocking her into an old manor of a man, crumbling brickwork, mould-eaten walls, gates off their hinges, ghosts who whispered into his ear, commanding him to hoard, as his only guests.

“I need to pay the taxi,” she says.

“Give him the only thing you have, then. And swim next time if you don’t like the arrangement.”

A violent blow unlike any wave to have ever made their house sway now makes it spasm. Below, Taxi Man bellows with an axe in his hands, ready to deliver another hit to their weathered stilts: “My payment or you sleep in the sea tonight!”

Zahra walks past her husband. He grabs her wrist. “Where is it?”

How Kareem could have ever spotted such an inconspicuous trifle missing from his reserve is a mystery to Zahra. She wants to ask him, Is it an artefact? Are you hoping to sell it to the British Museum? But he had laid into her for less.

Now, as Kareem extracts vows from her to never so much as look at the cage again, Taxi Man pronounces his sharp threats, the house shudders, and the latch comes unlatched, displacing some of the stash and freeing the dog, who stands over them while Zahra struggles under her opponent, cheering on the wrestling match as though she’d placed bets on it, bits of her frothing spit landing on Zahra’s cheek. Kareem bears down on her neck and carbon dioxide accumulates in her body and a single thought forms in her mind with striking lucidity given the circumstances: Would she look like Warda’s husband, purple and ready to pop? Fear fuels her last act of resistance, and she feels around her body for the green hook. The house cedes to a final blow from Taxi Man’s axe and collapses just as Kareem howls and his hands shoot up to cover his left eye, where she pierced him with the hook’s fighting edge.

The fall lasts forever and for only a fraction of a second.

Below the water, Zelda dances in slow motion, twisting among the thick debris to propel herself to the surface. Above, it rains paper money, along with clouds of salaam that gently float down and meet the scream in Zahra’s throat, coating her lungs and stretching fingers up to her brain, where they curl onto themselves and hold. She clings to the floating cage and sees Taxi Man fighting to keep sure footing in his ramshackle vehicle as he snatches at the air for falling bills.

“Satisfied now?” she asks him, turning onto her back to look up at the night sky and seeing herself instead, in sunglasses, with a cigarette poised between fore and middle finger.

“Warda, ya Warda, the One Who Pushes Through Cracks in Concrete. So you did it!” Humbaba says, floating next to her on the rocking chair where Kareem would sit and survey his day’s gains — a butane gas lighter, a titanium tooth implant, a bicycle wheel. On her lap is dear little Najmi with sparkling stars in his fur.

“I can’t be here anymore,” Zahra says to her.

“Lakan — leave!”

“Come with me. I’ll carry you across my back, and we’ll cross the sea to the other side. What are you even doing for that sorry old tree?”

Behind Humbaba, unending acres of lush green cedars and a mezze table as long as the coastal highway.

When Zahra comes to, it is morning. Kareem lies belly up on the front door of their ruined house, Zelda’s jaws working through his entrails, pulling up her prize — his ghammeh — and snapping away at it.

“Such is nature,” she says. She remembers her plan, flashes of her body cutting westward through seawater like a dolphin as Kareem squeezed strobing visions into her oxygen-starved mind. “So, this is what we leave behind?”

A sinking ship. Stalwart Humbaba and her melancholy tree.

The green hook calls to her with a well-timed wink of sunlight as it floats by. She pockets it for good luck.

Zahra registers with mild surprise the texture of something other than water beneath her fingertips. The sea crawls over her body and pulls, begging her to come back. Do you think I am as easy as the rocks you’ve battered down to grains? I’ve killed, you know! She drags herself further up the shore. She hears the voice of a child.

“Zikra, c’est une sirène!”

The crunch of sand beneath boots.

“C’est juste une femme,” Zikra says. “But please, Arabic, Barakah.”

Barakah

“Qu’as tu dans ta main?”

At first, they feigned kindness when they asked.

“Won’t you show us what you’ve got in your hand, little one?”

All patronizing grins and stooped shoulders in the way of adults who imagined they could swap sincerity with saccharine sweetness and go undetected by the children they hoped to dupe.

“Show us, girl.”

The Merciful Sisters of the Adoration of Perpetual Crises, Barakah thought, might have been more accurately named the Intrusive Sisters or the Meddlesome Sisters or the Inquisitory Sisters. They hated that she guarded something from them.

They had begun to scheme on how to obtain the secret Barakah held in her hand, preferably through non-violence so as not to rouse the suspicion of the many money-mahshi voluntourists at the orphanage. Bless us with more children, read the wrought-iron sign over its entry gate, a prayer answered abundantly, a cup overflowing.

“Why won’t you show us? Is it because you know you are holding something evil? Something dangerous maybe?”

Smiles into sneers into threats, but Barakah’s small hand remained a mighty fist, one they eventually tried to pry open with force, receiving bites that bled in the process.

“You will never be adopted,” one sister pronounced gleefully, dousing her injured hand with anti-septic.

Barakah marvelled at their ugliness, which adults refused to see. They never came close enough to the sisters to see them for who they really were and thus never saw the fault lines in their patchwork papyrus skin, taut hermetic-tight over brickly bone. They never saw them from the necessary vantage point, heads at their hip-level and looking up into black nostrils crowded with spiderwebs and loose folds of flesh stitched back under their chins to not belie their decline. They never saw how, at night, they hung rightside wrong and huddled together from the rafters, bats in black habits and wimples.

But all their grotesqueness mattered little to Barakah because she could retreat into her secret.

It had come to her by pigeon beak on a breezy morning. She had been banished to an empty dormitory as they all performed Sunday worship. For so slight an infraction as a growl during prayer, imagine. The sisters had thought it punishment, oblivious to the effervescent delight Barakah kept hidden behind pressed lips and blank eyes, little left fist by her side like she was gearing for a fight. Alone, she’d stared out the window to a playfield of tyres and pipes and scaffolding and shell casings and traced her mind’s fingers over a fading memory of her father’s face, blurring at the edges evermore with passing time. He was tall and kind of smile, and he would fashion meals and toys from scraps and his own ingenuity, a golden dusting of improbability that breathed magic into the mundane and taught her that beauty was the banal seen through clever, playful eyes.

“Carry a message for me,” she told the wind as it touched a hand to her forehead, reminding her of when Baba would feel her for fever, “Tell him I miss him.” It did as she said and changed directions towards the port, lifting her hair as though tempting her to join it, and it was in that moment she saw the pigeon, struggling against its flow, carrying something unwieldly between maxillary and mandibular rostra. It drew closer and closer until it reached her window and landed on the ledge, tucking its wings in and disappearing on scaly foot off to the side.

Barakah stuck her head out and followed the bird with her eyes. It deposited the thing like an offering into a spacious nest where a mother waited over eggs, warming them with her body, and where other objects were collected off to the side like gifts at the foot of a Christmas tree — flowers stolen from graves, a diamond tennis bracelet, a pin badge in the shape of a shield. This latest addition was a piece of green porcelain with small protrusions and sharp edges on either side, as though it were once part of a whole, perhaps the handle to an amphora.

Already, she knew it was hers. She didn’t like to steal, but mustn’t the pigeon have stolen it from somewhere too?

“Plus,” she told the feathered couple as they watched her apprehensively, “it has sharp edges. It won’t be good for your little ones. And God help you if the sisters should see it shine like that. They’ll take it, you know, and destroy your home for the fun of it.”

She hid her secret under the closed lid of a toilet tank, third stall from the door, and kept a red herring balled into her left hand ever since. If they suspected something there, they wouldn’t look for it elsewhere.

One night, a sister came for her.

“It seems you’ve made an impression,” she sneered, baring tiny sharp teeth.

Barakah followed the sister down the coffin-shaped corridor that led to an office she had never been called to before but knew was where prospective parents went to discuss serious matters, all the time wondering whom she had impressed and how.

And that’s when she saw the woman she would leave with before the end of the year. Wild black mane marbled with white, a long grey overcoat that obscured her body, a spyglass at her hip, an unmoving glass eye, and the shiny skin of a burn wound on the side of her forehead above it and her cheek below it. She never once asked what Barakah pretended to hold in her fist, and she never bent down to talk to her.

“What should I call you?” Barakah asked her.

“Zikra,” she said, sounding very sad.

They were alone in the playfield under a muggy, mottled sky when Zikra said in her soft, breathless voice: “I need your help. I’ve been tasked with a very important mission, and I like the way you guard what’s important to you.”

“Why can’t you do it yourself?”

“I’m dying.”

“What’s in it for me?” Barakah asked, watching the dormitory window as the new parents carried cracked eggshells away from their nest.

“A chance to get away from here.”

When they readied to leave, the woman looked at her and asked, “Haven’t you anything to bring with you?”

Barakah asked if she could keep a secret. Zikra nodded.

“And what is special about this?” she asked, examining the green porcelain, turning it over between her fingers.

“It was mine when I had nothing.”

“And so it shall remain yours. Say fare poorly to the sisters.”

Barakah turned back into the orphanage for a final time and stood in front of the committee. Smiling, she held her fist out and opened it, empty palm facing vaulted ceiling. Her victory, their gnawing disappointment in the space between. An eruption of new wings from the dormitory window.

“Did you know that a salamander can regenerate its limbs?” Zikra says as they walk by the river in front of her estate.

It drains into the Mediterranean, she had said of that sinuous waterway on Barakah’s first day on the island.

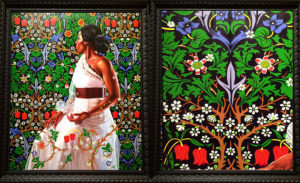

The mermaid who calls herself Warda lies on a lawn chair, watching them from behind her sunglasses and puffing on a cigarette. She looks different than the day she showed up on their shore. Healthier, with the arrogance of the accomplished. She is unmoved by their undertaking, sceptical of its value and success.

Barakah has begun to see the animal everywhere, in the scurry of field mice and lizards, in the flutter of birds fleeing their footsteps. In the fantasy landscapes of her waking reveries and in the vespertine layers of deep dreams, Zikra’s fixation seeping into her pores and settling behind her eyelids, ready to pounce at every stimulus.

It is one of a kind, Zikra told her. No one has captured it before, but it is as real as the ground you walk on, Barakah, and one minute spent looking into its eyes is enough to bless you with a feeling of home that lasts forever.

“Alas,” she mutters under her breath, looking to the figure atop the hill behind the estate, “you are too big to be a salamander.”

Under the dimming sky, a silhouette. The magnetism of something more than chance pooling the incongruous together into meaning.

“Such activity on this island as I’ve never seen,” says Zikra, squinting at the stranger through her spyglass.

Zikra

A young man. When he walks, his ornaments herald his presence: the rainstick shake of beads from bracelets at his ankles and wrists, the whisper of fabrics touching and parting. He holds his hand to an azure turban. Cape and pantaloons billow with the breeze like sails. A heavy pendant at his chest, a ring on every finger.

The details of his person shift into focus as he approaches them, and Zikra is reminded of all the things she mistook for her salamander, the many mirages induced by poor eyesight and distance, formidable shadows cast by small branches, smiling and scowling faces in the most unlikely places.

“Who are you?” Zikra asks him.

“I am Amir,” Amir says.

Wrapped around his head, a United Nations tee-shirt, its globe and laurel wreath positioned in the space between his black eyes. At his ankles and wrists, obsolete, hole-punched coins threaded through with zip ties. His cape is a bedsheet, his rings beer and soda bottle caps, his pendant the porcelain head of what looks to be a snake.

“I was never supposed to see them,” Amir says as they sit around the fire pit and he recounts the story of how he came to be a fugitive.

“But how can you tell one day from the next until it is different? It was a day like any other day, and as such, I hiked through the hills and valleys of rubbish in search of something I could fashion into fashion, art from the discarded, use from the abandoned.”

It was how he found the sequins that now adorn his vest, the empty Coke bottles from which he built his raft to sail to the island.

“The others made fun of me. For them, it was a useless pursuit. But what is more useless than waiting for something better to come to you? I might be wearing rubbish, but you tell me whether, for a moment, you did not mistake me for a prince!”

No one argues.

“I was outside Parliament when I saw it in one of the windows.” He touches his fingers to the colubrine head. “It looked so real. Alive. And it was staring at me like a prisoner crying for help with those mesmerizing mirrorball eyes that drew light to them and multiplied it millionfold. I was bewitched. Most of the security had been diverted to the other end of the city because of a riot, so I took my chances and went inside and got it.” He holds up his pendant proudly. “And there they were.”

The president, the speaker, the party leaders, all filling the seats as though they were still locked in talks, but over the hall reigned a thick, static silence and the ancient smell of an undisturbed crypt.

“At first, I thought they might have been puppets, dummy mummies. But as soon as I touched the president, he fell forward and shattered like a sandcastle against the desk, sending up dust into my eyes and nose. And that’s when I started to sneeze. I outran the drones that came for me, but why should I have to hide forever when I’ve done nothing wrong? Unless it’s this they’re after,’ he looked down to the pendant at his sternum again.

“The living are an inconvenient presence in the realm of the dead,” Warda says, falling back into her unbothered state.

“Who oversees the country then, if they are all dead? Whose drones followed you?” Barakah asks.

Amir looks at her sadly, red-winged, yellow-bodied bird dancing between them and on the reflective surface of his pendant. Zikra has seen the shape of that tapered head before, its colorful kaleidoscopic eyes.

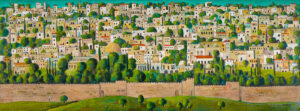

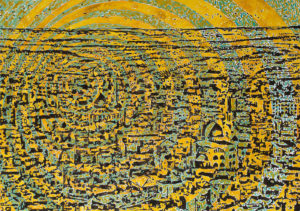

Zikra remembers little besides the beautiful stories of Backhome, a place she could see from the island, a place that sent up chemical vapors like a factory’s smokestacks, that whistled and rattled with unrest yet beckoned to her with the pull of a terrible drug. She remembers having a mother and father who told her those stories, planting germs of yearning inside her that would steadily bloom into stalks and multiply into fields until her body grew too small to contain all that desire for a place she’d never really known but would try nonetheless to recreate on her island, populating it with rescued relics of the past — vinyl records, photographs, books, a reminder in every architectural detail of the estate, a fingerprint in its mashrabiya and arcade windows, exhumed semiotic signifiers to create a sense of place in the displaced. Of all the stories, though — of forests and beaches and mountain slopes and valleys and barbecues and crystalline brooks and ancient ruins and dazzling cities and glorious food and shahs and emirs — that of the salamander was the most excruciatingly enduring one, fermenting into an obsession that bordered on the malignant, bubbling just barely under her skin and erupting with every disappointment. She would find it, or she would die trying. And nearly died she almost had, scrambling after some slinky amphibian to the edge of a volcanic crater, liquid sulphur seeping from its cracks, and rushing into a sudden plume of blue fire that took her eye, the soft skin above and beneath it, and years of her life. Illusion after illusion, encounters with danger built upon dangerous encounters until her body became a storybook of consequences, ripe for reaping, alveoli steadily deflating, bronchioles brittle. Breathing, that industry that in others asked for nothing in return, demanded of her a formidable attention. Such was nature: always up for a duel so it could beat you.

She lied to herself that Barakah would be more even-tempered, more slow-and-steady-wins-the-race, when she knew from the moment she saw her at the orphanage that the girl was all potential, wild determination in every excitable cell of her. Zikra was almost sorry to recruit her into that carnivore’s life, so much energy expended in empty pursuit of such a light-footed thing as a dream, always leaping out of reach.

“I won’t be here for long, but I’ll be watching from wherever I go afterwards,” she had slurred one evening, unstopping a decanter of liqueur she had just stopped up, chest-deep in a pit of insecurity, hope a flickering thing in a cold corner of her ribcage.

“You don’t need to threaten me,” Barakah had said. “I want to find it too.”

“The others say it doesn’t exist. For them, it is a useless enterprise.”

“What is useless is sitting around ridiculing others for chasing their dreams instead of finding their own.”

The newcomer mourns at night, cape trailing behind him as he circles the estate in slow, measured steps like a ghost condemned to a moment on eternal repeat. During the day, he strategizes on how to de-patriate all the people he has left behind and bring them to the island, casualties of his reckless promises to remember them when he reached paradise.

“You know what the diplotourists would say to us?” Amir says. Every so often, he pauses to indulge his anger. “They would say, ‘Look how you can see the stars now with no light pollution!’ And we would look into that uncaring sky and wish for the warm glow of home, of civilization, of a kitchen or living room lit up with something other than foreign searchlights!”

When at last he sleeps, when it is almost morning, Zikra creeps into his room and finds the pendant on the commode by the window. Then, she goes to Barakah’s room, where the girl’s secret lies bare and trusting in a nest of discarded clothing. Warda’s good luck charm too is defenseless, heaped in together with a pile of curios — a vintage poster for the Hotel Riviera, a stamp with Emir Bashir Shihab II’s face on it, a red-white-and-green lighter with a map showing Tripoli, Fakeha, Byblos, Baalbeck, Zahle, Beit-Eddine, Jeita, Anjar, the Moussa Castle, and Tyre.

“How cruel,” Zikra whispers once she has assembled the pieces. She sits at a table under the gazebo where yesterday Warda played casse-tête and stares at the porcelain likeness of her salamander, divided against itself, head-body-tail. Alone as night lifts and its chilled air sinks to the river, she weeps for all the time siphoned from her. A million ways to keep alive a legend was all she would ever know — drawings, etchings, oral histories, near-sightings. “How cruel to pass a sickness onto your children.”

She rests her head onto the mist-damp wooden table and sleeps.

The Salamander

It is a glorious thing to be whole again. It takes me a second to find my footing, but once I do, I dart into the tall wet grass by the bank and scuttle through it before dropping into the water — and she after me. For less than a moment, we look at each other, suspended in that quiet limpid world. Her eyes are wide, and her striated hair swells around her. I am sorry to go, but she asks too great a sacrifice of me to stay and offer myself up for study. Ah, the adventures I went on though, the phenomena I saw, the way I was loved! I could not ask for more. I leave all this behind, unafraid.

It is known that salamanders swim far better, faster, and farther than humans. I plan to reach the sea within the day, and from there, who knows? Byblos, Tripoli, Tyre, Beirut…

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)