Gaza City, Al Jalaa Street (photo Abdallah ElHajj, Getty Images).

Excerpted by special arrangement with the author from his recent book Ten Myths About Israel.

Ilan Pappe

“The Gaza Mythologies” is excerpted from Ten Myths About Israel which is available from Verso Books.

The issue of Palestine is closely associated in international public opinion with the Gaza Strip. Ever since the first Israeli assault on the Strip in 2006, and up to the recent 2014 bombardment of the 1.8 million Palestinians living there, this part of the region epitomized the Palestine question for the world at large. I will present in this chapter three myths which mislead public opinion about the causes of the ongoing violence in Gaza, and which explain the helplessness felt by anyone wishing to end the misery of the people crammed into one of the world’s most densely populated pieces of land.

The first myth refers to one of the main actors on the ground in the Strip: the Hamas movement. Its name is the Arabic acronym for “Islamic Resistance Movement,” and the word hamas also literally means “enthusiasm.” It grew out of a local branch of the Islamic fundamentalist movement, the Muslim Brotherhood, in Egypt in the second half of the 1980s. It began as a charity and educational organization but was transformed into a political movement during the First Intifada in 1987. The following year it published a charter asserting that only the dogmas of political Islam had a chance of liberating Palestine. How these dogmas were to be implemented or what they really mean was never fully explained or demonstrated. From its inception up to the present, Hamas has been involved in an existential struggle against the West, Israel, the Palestinian Authority (PA), and Egypt.

When Hamas surfaced in the late 1980s, its main rival in the Gaza Strip was the Fatah movement, the main organization within, and founder of, the PLO. It lost some support among the Palestinian people when it negotiated the Oslo Accord and founded the Palestinian Authority (hence the chair of the PLO is also the president of the PA and the head of Fatah). Fatah is a secular national movement, with strong left-wing elements, inspired by the Third World liberation ideologies of the 1950s and 1960s and in essence still committed to the creation in Palestine of a democratic and secular state for all.

Strategically, however, Fatah has been committed to the two-states solution since the 1970s. Hamas, for its part, is willing to allow Israel to withdraw fully from all the occupied territories, with a ten-year armistice to follow before it will discuss any future solution.

Hamas challenged Fatah’s pro-Oslo policy, its lack of attention to social and economic welfare, and its basic failure to end the occupation. The challenge became more significant when, in the mid-2000s, Hamas decided to run as a political party in municipal and national elections. Hamas’s popularity in both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip had grown thanks to the prominent role it played in the Second Intifada in 2000, in which its members were willing to become human bombs, or at least to take a more active role in resisting the occupation (one should point out that during that Intifada young members of Fatah also showed the same resilience and commitment, and Marwan Barghouti, one of their iconic leaders, is still in jail in Israel for his role in the uprising).

Yasser Arafat’s death in November 2004 created a political vacuum in the leadership, and the Palestinian Authority, in accordance with its own constitution, had to conduct presidential elections. Hamas boycotted these elections, claiming that they would be too closely associated with the Oslo process and less so with democracy. It did, however, participate that same year, 2005, in municipal elections, in which it did very well, taking control of over one-third of the municipalities in the occupied territories. It did even better in the elections in 2006 to the parliament—the legislative assembly of the PA as it is called. It won a comfortable majority in the assembly and therefore had the right to form the government—which it did for a short while, before clashing with both Fatah and Israel. In the ensuing struggle, it was ousted from official political power in the West Bank, but took over the Gaza Strip. Hamas’s unwillingness to accept the Oslo Accord, its refusal to recognize Israel, and its commitment to armed struggle form the background to the first myth I examine here.

Hamas is branded as a terrorist organization, both in the media and in legislation. I will claim that it is a liberation movement, and a legitimate one at that.

The second myth I examine concerns the Israeli decision that created the vacuum in the Gaza Strip which enabled Hamas not only to win the elections in 2006 but also to oust Fatah by force in the same year. This was the 2005 unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the Strip after nearly forty years of occupation. The second myth is that this withdrawal was a gesture of peace or reconciliation, which was reciprocated by hostility and violence. It is crucial to debate, as I do in this chapter, the origins of the Israeli decision and to look closely at the impact it has had on Gaza ever since. In fact, I claim that the decision was part of a strategy intended to strengthen Israel’s hold over the West Bank and to turn the Gaza Strip into a mega-prison that could be guarded and monitored from the outside. Israel not only withdrew its army and secret service from the Strip but also pulled out, in a very painful process, the thousands of Jewish settlers the government had sent there since 1969. So, I will claim that viewing this decision as a peaceful gesture is a myth. It was more a strategic deployment of forces that enabled Israel to respond harshly to the Hamas victory, with disastrous consequences for the population of Gaza.

And indeed, the third and last myth I will look at is Israel’s claim that its actions since 2006 have been part of a self-defensive war against terror. I will venture to call it, as I have done elsewhere, an incremental genocide of the people of Gaza.

Myth #1 — Hamas Is a Terrorist Organization

The victory of Hamas in the 2006 general elections triggered a wave of Islamophobic reaction in Israel. From this moment on, the demonization of the Palestinians as abhorred “Arabs” was enhanced with the new label of “fanatical Muslims.” The language of hate was accompanied by new aggressive anti-Palestinian policies that aggravated the situation in the occupied territories beyond its already dismal and atrocious state.

There have been other outbreaks of Islamophobia in Israel in the past. The first was in the late 1980s, when a very small number of Palestinian workers—forty people out of a community of 150,000—were involved in stabbing incidents against their Jewish employers and passersby. In the aftermath of the attacks Israeli academics, journalists, and politicians related the stabbing to Islam—religion and culture alike—without any reference to the occupation or the slavish labor market that developed on its margins. [1] A far more severe wave of Islamophobia broke out during the Second Intifada in October 2000. Since the militarized uprising was mainly carried out by Islamic groups—especially suicide bombers—it was easier for the Israeli political elite and media to demonize “Islam” in the eyes of many Israelis. [2] A third wave began in 2006, in the wake of Hamas’s victory in the elections to the Palestinian parliament. The same characteristics of the previous two waves were apparent in this one as well. The most salient feature is the reductionist view of everything Muslim as being associated with violence, terror, and inhumanity.

As I have shown in my book, The Idea of Israel,[3] between 1948 and 1982 Palestinians were demonized by comparisons with the Nazis.[4] The same process of “Nazifying” the Palestinians is now applied to Islam in general, and to activists in its name in particular. This has continued for as long as Hamas and its sister organization, Islamic Jihad, have engaged in military, guerrilla, and terror activity. In effect, the rhetoric of extremism wiped out the rich history of political Islam in Palestine, as well as the wide-ranging social

and cultural activities that Hamas has undertaken ever since its inception.

A more neutral analysis shows how far-fetched the demonized image of Hamas as a group of ruthless and insane fanatics is. [5] Like other movements within political Islam, the movement reflected a complex local reaction to the harsh realities of occupation, and a response to the disorientated paths offered by secular and socialist Palestinian forces in the past. Those with a more engaged analysis of this situation were well prepared for the Hamas triumph in the 2006 elections, unlike the Israeli, American, and European governments. It is ironic that it was the pundits and orientalists, not to mention Israeli politicians and chiefs of intelligence, who were taken by surprise by the election results more than anyone else. What particularly dumbfounded the great experts on Islam in Israel was the democratic nature of the victory. In their collective reading, fanatical Muslims were meant to be neither democratic nor popular. These same experts displayed a similar misunderstanding of the past. Ever since the rise of political Islam in Iran and in the Arab world, the community of experts in Israel had behaved as if the impossible was unfolding in front of their eyes.

Misunderstandings, and therefore false predictions, have characterized the Israeli assessment of the Palestinians for a long time, especially with regard to the political Islamic forces within Palestine. In 1976, the first Rabin government allowed municipal elections to take place in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. They calculated, wrongly, that the old cadre of pro-Jordanian politicians would be elected in the West Bank and the pro-Egyptian ones in the Strip. The electorate voted overwhelmingly for PLO candidates.[6] This surprised the Israelis, but it should not have. After all, the expansion of the PLO’s power and popularity ran parallel to a concerted effort by Israel to curb, if not altogether eliminate, the secular and socialist movements within Palestinian society, whether in the refugee camps or inside the occupied territories. Indeed, Hamas became a significant player on the ground in part thanks to the Israeli policy of encouraging the construction of an Islamic educational infrastructure in Gaza as a counterbalance to the grip of the secular Fatah movement on the local population.

In 2009, Avner Cohen, who served in the Gaza Strip around the time Hamas began to gain power in the late 1980s, and was responsible for religious affairs in the occupied territories, told the Wall Street Journal, “the Hamas, to my great regret, is Israel’s creation.” [7] Cohen explains how Israel helped the charity al-Mujama al-Islamiya (the “Islamic Society”), founded by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin in 1979, to become a powerful political movement, out of which the Hamas movement emerged in 1987. Sheikh Yassin, a crippled, semi-blind Islamic cleric, founded Hamas and was its spiritual leader until his assassination in 2004. He was originally approached by Israel with an offer of help and the promise of a license to expand. The Israelis hoped that, through his charity and educational work, this charismatic leader would counterbalance the power of the secular Fatah in the Gaza Strip and beyond. It is noteworthy that in the late 1970s Israel, like the United States and Britain, saw secular national movements (whose absence today they lament) as the worst enemy of the West.

In his book To Know the Hamas, the Israeli journalist Shlomi Eldar tells a similar story about the strong links between Yassin and Israel.[8] With Israel’s blessing and support, the “Society” opened a university in 1979, an independent school system, and a network of clubs and mosques. In 2014, the Washington Post drew its own very similar conclusions about the close relationship between Israel and the “Society” until its transformation into Hamas in 1988. [9] In 1993, Hamas became the main opposition to the Oslo Accord. While there was still support for Oslo, it saw a drop in its popularity; however, as Israel began to renege on almost all the pledges it had made during the negotiations, support for Hamas once again received a boost. Particularly important was Israel’s settlement policy and its excessive use of force against the civilian population in the territories.

But Hamas’s popularity among the Palestinians did not depend solely on the success or failure of the Oslo Accord. It also captured the hearts and minds of many Muslims (who make up the majority in the occupied territories) due the failure of secular modernity to find solutions to the daily hardships of life under occupation. As with other political Islamic groups around the Arab world, the failure of secular movements to provide employment, welfare, and economic security drove many people back into religion, which offered solace as well as established charity and solidarity networks. In the Middle East as a whole, as in the world at large, modernization and secularization benefited the few but left many unhappy, poor, and bitter. Religion seemed a panacea—and at times even a political option.

Hamas struggled hard to win a large share of public support while Arafat was still alive, but his death in 2004 created a vacuum that it was not immediately able to fill. Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) did not enjoy the same legitimacy and respect as his predecessor. The fact that Arafat was delegitimized by Israel and the West, while Abu Mazen was accepted by them as Palestinian president, reduced his popularity among the younger generation, in the de-developed rural areas, and in the impoverished refugee camps. The new Israeli methods of oppression introduced during the Second Intifada—particularly the building of the wall, the roadblocks, and the targeted assassinations—further diminished the support for the Palestinian Authority and “increased the popularity and prestige of Hamas. It would be fair to conclude, then, that successive Israeli governments did all they could to leave the Palestinians with no option but to trust, and vote for, the one group prepared to resist an occupation described by the renowned American author Michael Chabon as “the most grievous injustice I have seen in my life.” [10]

The only explanation for the rise of Hamas offered by most Israeli “experts” on Palestinian affairs, inside and outside the establishment, involved appealing to Samuel Huntington’s neoconservative model of the “clash of civilizations” as a way of understanding how history works. Huntington divided the world into two cultures, rational and irrational, which inevitably came into conflict. By voting for Hamas the Palestinians were supposedly proving themselves to be on the “irrational” side of history—an inevitable position given their religion and culture. Benjamin Netanyahu put it in even cruder terms when he talked about the cultural and moral abyss that separates the two peoples.[11]

The obvious failure of the Palestinian groups and individuals who had come to prominence on the promise of negotiations with Israel clearly made it seem as if there were very few alternatives. In this situation the apparent success of the Islamic militant groups in driving the Israelis out of the Gaza Strip offered some hope. However, there is more to it than this. Hamas is now deeply embedded in Palestinian society thanks to its genuine attempts to alleviate the suffering of ordinary people by providing schooling, medicine, and welfare. No less important, Hamas’s position on the 1948 refugees’ right of return, unlike the PA’s stance, was clear and unambiguous. Hamas openly endorsed this right, while the PA sent out ambiguous messages, including a speech by Abu Mazen in which he rescinded his own right to return to his hometown of Safad.

Myth #2—The Israeli Disengagement Was an Act of Peace

The Gaza Strip amounts to slightly more than 2 percent of the landmass of Palestine. This small detail is never mentioned whenever the Strip is in the news, nor was it mentioned in the Western media coverage

of the dramatic events in Gaza in the summer of 2014. Indeed, it is such a small part of the country that it has never existed as a separate region in the past. Before the Zionization of Palestine in 1948, Gaza’s history was not unique or different from the rest of Palestine, and it had always been connected administratively and politically to the rest of the country. As one of Palestine’s principal land and sea gates to the world, it tended to develop a more flexible and cosmopolitan way of life, not dissimilar to other gateway societies in the Eastern Mediterranean in the modern era. Its location on the coast and on the Via Maris from Egypt up to Lebanon brought with it prosperity and stability—until this was disrupted and nearly destroyed by the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948.

The Strip was created in the last days of the 1948 war. It was a zone into which the Israeli forces pushed hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from the city of Jaffa and its southern regions down into the town of Bir-Saba (Beersheba of today). Others were expelled to the zone from towns such as Majdal (Ashkelon) as late as 1950, in the final phases of the ethnic cleansing. Thus, a small pastoral part of Palestine became the biggest refugee camp on earth. It still like this today. Between 1948 and 1967, this huge refugee camp was delineated and severely restricted by the respective Israeli and Egyptian policies. Both states disallowed any movement out of the Strip, and as a result, living conditions became ever harsher as the number of inhabitants doubled. On the eve of the Israeli occupation in 1967, the catastrophic nature of this enforced demographic transformation was evident. Within two decades this once pastoral coastal part of southern Palestine became one of the world’s most densely inhabited areas, without the economic and occupational infrastructure to support it.

During the first twenty years of occupation, Israel did allow some movement outside the area, which was cordoned off with a fence. Tens of thousands of Palestinians were permitted to join the Israeli labor market as unskilled and underpaid workers. The price Israel demanded for this was total surrender. When this was not complied with, the free movement for laborers was withdrawn. In the lead up to the Oslo Accord in 1993, Israel attempted to fashion the Strip as an enclave, which the peace camp hoped would become either autonomous or a part of Egypt. Meanwhile the nationalist, right-wing camp wished to include it in the “Eretz Israel” they dreamed of establishing in place of Palestine.

The Oslo agreement enabled the Israelis to reaffirm the Strip’s status as a separate geopolitical entity—not just outside of Palestine as a whole, but also apart from the West Bank. Ostensibly, both were under Palestinian Authority control, but any human movement between them depended on Israel’s good will. This was a rare feature in the circumstances, and one that almost disappeared when Netanyahu came to power in 1996. At the same time, Israel controlled, as it still does today, the water and electricity infrastructure. Since 1993 it has used this control to ensure the well-being of the Jewish settler community on the one hand, and to blackmail the Palestinian population into submission on the other. Over the last fifty years, the people of the Strip have thus had to choose between being internees, hostages, or prisoners in an impossible human space.

It is in this historical context that we should view the violent clashes between Israel and Hamas since 2006. In light of that context, we must reject the description of Israeli actions as part of the “war against terror,” or as a “war of self-defense.” Nor should we accept the depiction of Hamas as an extension of al-Qaeda, as part of the Islamic State network, or as a mere pawn in a seditious Iranian plot to control the region. If there is an ugly side to Hamas’s presence in Gaza, it lies in the group’s early actions against other Palestinian factions in the years 2005 to 2007. The main clash was with Fatah in the Gaza Strip, and both sides contributed to the friction that eventually erupted into an open civil war. The clash erupted after Hamas won the legislative elections in 2006 and formed the government, which included a Hamas minister responsible for the security forces. In an attempt to weaken Hamas, President Abbas transferred that responsibility to the head of the Palestinian secret service—a Fatah member. Hamas responded by setting up its own security forces in the Strip.

In December 2006, a violent confrontation in the Rafah crossing between the Presidential Guard and the Hamas security forces triggered a confrontation that would last until the summer of 2007. The Presidential Guard was a Fatah military unit, 3,000 strong, consisting mostly of troops loyal to Abbas. It had been trained by American advisers in Egypt and Jordan (Washington had allocated almost 60 million dollars to its maintenance). The incident was triggered by Israel’s refusal to allow the Hamas prime minister, Ismail Haniyeh, to enter the Strip—he was carrying cash donations from the Arab world, reported to be tens of millions of dollars. The Hamas forces then stormed the border control, manned by the Presidential Guard, and fighting broke out. [12]

The situation deteriorated quickly thereafter. Haniyeh’s car was attacked after he crossed into the Strip. Hamas blamed Fatah for the attacks. Clashes broke out in the Strip and in the West Bank as well. In the same month, the Palestinian Authority decided to remove the Hamas-led government and replace it with an emergency cabinet. This sparked the most serious clashes between the two sides, which lasted until the end of May 2007, leaving dozens of dead and many wounded (it is estimated that 120 people died). The conflict only ended when the government of Palestine was split into two: one in Ramallah and one in Gaza. [13]

While both sides were responsible for the carnage, there was also (as we have learned from the Palestine papers, leaked to Al Jazeera in 2007) an external factor that pitted Fatah against Hamas. The idea of preempting a possible Hamas stronghold in the Gaza Strip, once the Israelis withdrew, was suggested to Fatah as early as 2004 by the British intelligence agency MI6, who drew up a security plan that was meant to “encourage and enable the Palestinian Authority to fully meet its security obligations … by degrading the capabilities of the rejectionists (which later on the document names as the Hamas).” [14] The British prime minister at the time, Tony Blair, had taken a special interest in the Palestine question, hoping to have an impact that would vindicate, or absolve, his disastrous adventure in Iraq. The Guardian summarized his involvement as that of encouraging Fatah to crack down on Hamas. [15] Similar advice was given to Fatah by Israel and the United States, in a bid to keep Hamas from taking over the Gaza Strip. However, things got scrappy and the preemptive plan backfired in multiple ways.

This was in part a struggle between politicians who were democratically elected and those who still found it hard to accept the verdict of the public. But that was hardly the whole story. What unfolded in Gaza was a battle between the United States’ and Israel’s local proxies—mainly Fatah and PA members, most of whom became proxies unintentionally, but nonetheless danced to Israel’s tune—and those who opposed them. The way Hamas acted against other factions was later reciprocated by the action the PA took against them in the West Bank. One would find it very hard to condone or cheer either action. Nevertheless, one can fully understand why secular Palestinians would oppose the creation of a theocracy, and, as in many other parts of the Middle East, the struggle over the role of religion and tradition in society will also continue in Palestine. However, for the time being, Hamas enjoys the support, and in many ways the admiration, of many secular Palestinians for the vigor of its struggle against Israel. Indeed, that struggle is the real issue. According

to the official narrative, Hamas is a terrorist organization engaging in vicious acts perpetrated against a peaceful Israel that has withdrawn from the Gaza Strip. But did Israel withdraw for the sake of peace? The answer is a resounding no.

To get a better understanding of the issue we need to go back to April 18, 2004, the day after the Hamas leader Abdul Aziz al-Rantissi was assassinated. On that day, Yuval Steinitz, chairman of the foreign affairs and defense committee in the Knesset and a close aide to Benjamin Netanyahu, was interviewed on Israeli radio. Before becoming a politician, he had taught Western philosophy at the University of Haifa. Steinitz claimed that his worldview had been shaped by Descartes, but it seems that as a politician he was more influenced by romantic nationalists such as Gobineau and Fichte, who stressed purity of race as a precondition for national excellence. [16] The translation of these European notions of racial superiority into the Israeli context became evident as soon as the interviewer asked him about the government’s plans for the remaining Palestinian leaders. Interviewer and interviewee giggled as they agreed that the policy should involve the assassination or expulsion of the entire current leadership, that is all the members of the Palestinian Authority—about 40,000 people. “I am so happy,” Steinitz said, “that the Americans have finally come to their senses and are fully supporting our policies.” [17] On the same day, Benny Morris of Ben-Gurion University repeated his support for the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians, claiming that this was the best way of solving the conflict. [18]

Opinions that used to be considered at best marginal, at worst lunatic, were now at the heart of the Israeli Jewish consensus, disseminated by establishment academics on prime-time television as the one and only truth. Israel in 2004 was a paranoid society, determined to bring the conflict to an end by force and destruction, whatever the cost to its society or its potential victims. Often this elite was supported only by the US administration and the Western political elites, while the rest of the world’s more conscientious observers watched helpless and bewildered. Israel was like a plane flying on autopilot; the course was preplanned, the speed predetermined. The destination was the creation of a Greater Israel, which would include half the West Bank and a small part of the Gaza Strip (thus amounting to almost 90 percent of historical Palestine). A Greater Israel without a Palestinian presence, with high walls separating it from the indigenous population, who were to be crammed into two huge prison camps in Gaza and what was left of the West Bank. In this vision, the Palestinians in Israel could either join the millions of refugees languishing in the camps, or submit to an apartheid system of discrimination and abuse.

That same year, 2004, the Americans supervised what they called the “Road Map” to peace. This was a ludicrous idea initially put forward in the summer of 2002 by President Bush, and even more far-fetched than the Oslo Accord. The idea was that the Palestinians would be offered an economic recovery plan, and a reduction in the Israeli military presence in parts of the occupied territories, for about three years. After that another summit would, somehow, bring the conflict to an end for once and for all.

In many parts of the Western world, the media took the Road Map and the Israeli vision of a Greater Israel (including autonomous Palestinian enclaves) to be one and the same—presenting both as offering the only safe route to peace and stability. The mission of making this vision a reality was entrusted to “the Quartet” (aka the Middle East Quartet, or occasionally the Madrid Quartet), set up in 2002 to allow the UN, the United States, Russia, and the EU to work together towards peace in Israel-Palestine. Essentially a coordinating body consisting of the foreign ministers of all four members, the Quartet became more active in 2007 when it appointed Tony Blair as its special envoy to the Middle East. Blair hired the whole new wing of the legendary American Colony hotel in Jerusalem as his headquarters. This, like Blair’s salary, was an expensive operation that produced nothing.

The Quartet’s spokespersons employed a discourse of peace that included references to a full Israeli withdrawal, the end of Jewish settlements, and a two-states solution. This inspired hope among some observers who still believed that this course made sense. However, on the ground, the Road Map, like the Oslo Accord, allowed Israel to continue to implement its unilateral plan of creating the Greater Israel. The difference was that, this time, it was Ariel Sharon who was the architect, a far more focused and determined politician than Rabin, Peres, or Netanyahu. He had one surprising gambit that very few predicted: offering to evict the Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip. Sharon threw this proposal into the air in 2003, and then pressured his colleagues to adopt it, which they did within a year and half. In 2005, the army was sent in to evict the reluctant settlers by force. What lay behind this decision

Successive Israeli governments had been very clear about the future of the West Bank, while not so sure about what should happen with the Gaza Strip. [19] The strategy for the West Bank was to ensure it remained under Israeli rule, direct or indirect. Most governments since 1967, including Sharon’s, hoped that this rule would be organized as part of a “peace process.” The West Bank could become a state in this vision—if it remained a Bantustan. This was the old idea of Yigal Alon and Moshe Dayan from 1967; areas densely populated by Palestinians should be controlled from the outside. But things were different when it came to the Gaza Strip. Sharon had agreed with the original decision of the early governments, most of them Labor, to send settlers into the heart of the Gaza Strip, just as he supported the building of settlements in the Sinai Peninsula, which were evicted to the last under the bilateral peace agreement with Egypt. In the twenty-first century, he came to accept the pragmatic views of leading members of both the Likud and Labor parties on the possibility of leaving Gaza for the sake of keeping the West Bank. [20]

Prior to the Oslo process, the presence of Jewish settlers in the Strip did not complicate things, but once the new idea of a Palestinian Authority emerged, they became a liability to Israel rather than an asset. As a result, many Israeli policy makers, even those who did not immediately take to the idea of eviction, were looking for ways of pushing the Strip out of their minds and hearts. This became clear when, after the Accord was signed, the Strip was encircled with a barbed-wire fence and the movement of Gazan workers into Israel and the West Bank was severely restricted. Strategically, in the new setup, it was easier to control Gaza from the outside, but this was not entirely possible while the settler community remained inside.

One solution was to divide the Strip into a Jewish area, with direct access to Israel, and a Palestinian area. This worked well until the outbreak of the Second Intifada. The road connecting the settlements’ sprawl, the Gush Qatif block as it was called, was an easy target for the uprising. The vulnerability of the settlers was exposed in full. During this conflict the Israeli army tactics included massive bombardments and destruction of rebellious Palestinian pockets, which in April 2002 led to the massacre of innocent Palestinians in the Jenin refugee camp. These tactics were not easily implemented in the dense Gaza Strip due to the presence of the Jewish settlers. It was not surprising, then, that a year after the most brutal military assault on the West Bank, operation “Defensive Shield,” Sharon contemplated the removal of the Gaza settlers so as to facilitate a retaliation policy. In 2004, however, unable to force his political will on the Strip, he called instead for a series of assassinations of Hamas

leaders. Sharon hoped to influence the future with the assassinations of the two chief leaders, Abdul al-Rantisi and Sheikh Ahmed Yassin (killed on March 17, 2004). Even a sober source such as Haaretz assumed that after these assassinations, Hamas would lose its power base in the Gaza Strip and be reduced to an ineffective presence in Damascus, where, if need be, Israel would attack it too. The newspaper also was impressed by the US support for the assassinations (although both the paper and the Americans would be much less supportive of the policy later on). [21]

These killings took place before Hamas won the 2006 elections and took over the Gaza Strip. In other words, the Israeli policy did not undermine Hamas; on the contrary, it enhanced its popularity and power. Sharon wanted the Palestinian Authority to take control of Gaza and treat it like Area A in the West Bank; but this outcome did not materialize. So Sharon had to deal with Gaza in one of two ways: either clear out the settlers so that he could retaliate against Hamas without the risk of hurting Israeli citizens; or depart altogether from the region in order to refocus his efforts on annexing the West Bank, or parts of it. In order to ensure that the second alternative was understood internationally, Sharon orchestrated a charade that everybody fell for. As he began to make noises about evicting the settlers from the Strip, Gush Emunim compared the action to the Holocaust and staged a real show for the television when they were physically evicted from their homes. It seemed as if there were a civil war in Israel between those who supported the settlers and those on the left, including formidable foes of Sharon in the past, who supported his plan for a peace initiative. [22]

Inside Israel this move weakened, and in some cases entirely wiped out, dissenting voices. Sharon proposed that with the withdrawal from Gaza and the ascendance of Hamas therein, there was no point in pushing forward grand ideas such as the Oslo Accord. He suggested, and his successor after his terminal illness in 2007, Ehud Olmert, agreed, that the status quo be maintained for the time being. There was a need to contain Hamas in Gaza, but there was no rush to find a solution to the West Bank. Olmert called this policy unilateralism: since there were be no significant negotiations in the near future with the Palestinians, Israel should unilaterally decide which parts of the West Bank it wanted to annex, and which parts could be run autonomously by the Palestinian Authority. There was a sense among Israeli policy makers that, if not in public declarations, then at least as a reality on the ground, this course of action would be acceptable to both the Quartet and the PA. Until now, it had seemed to work.

With no strong international pressure and a feeble PA as a neighbor, most Israelis did not feel the strategy towards the West Bank to be an issue of great interest. As the election campaigns since 2005 have shown, Jewish society has preferred to debate socioeconomic issues, the role of religion in society, and the war against Hamas and Hezbollah. The main opposition party, the Labor Party, has more or less shared the vision of the coalition government, hence it has been both inside and outside government since 2005. When it came to the West Bank, or the solution to the Palestine question, Israeli Jewish society appeared to have reached a consensus. What cemented that sense of consensus was the eviction of the Gaza settlers by Sharon’s right-wing administration. For those who considered themselves to the left of the Likud, Sharon’s move was a peace gesture, and a brave confrontation with the settlers. He became a hero of the left as well of the center and moderate right, like de Gaulle taking the pied noir out of Algeria for the sake of peace. The Palestinian reaction in the Gaza Strip and criticism from the PA of Israeli policies ever since were seen as a proof of the absence of any sound or reliable Palestinian partner for peace.

Apart from brave journalists such as Gideon Levy and Amira Hass at Haaretz, a few members of the small left Zionist party Meretz, and some anti-Zionist groups, Jewish society in Israel became effectively silent, giving governments since 2005 carte blanche to pursue any policy towards the Palestinians they deem fit. This was why, in the 2011 protest movement that galvanized half a million Israelis (out of a population of 7 million) against the governments’ policies, the occupation and its horrors were not mentioned as part of the agenda. This absence of any public discourse or criticism had already allowed Sharon in his last year in power, 2005, to authorize more killings of unarmed Palestinians and, by way of curfews and long periods of closure, to starve the society under occupation. And when the Palestinians in the occupied territories occasionally rebelled, the government now had a license to react with even greater force and determination.

“Previous American governments had supported Israeli policies regardless of how they affected, or were perceived by, the Palestinians. This support, however, used to require negotiation and some give and take. Even after the outbreak of the Second Intifada in October 2000, some in Washington tried to distance the United States from Israel’s response to the uprising. For a while, Americans seemed uneasy about the fact that several Palestinians a day were being killed, and that a large number of the victims were children. There was also some discomfort about Israel’s use of collective punishments, house demolitions, and arrests without trial. But they got used to all this, and when the Israeli Jewish consensus sanctioned the assault on the West Bank in April 2002—an unprecedented episode of cruelty in the vicious history of the occupation—the US administration objected only to the unilateral acts of annexation and settlement that were expressly forbidden in the EU–American-sponsored Road Map.

In 2004, Sharon asked for US and UK support for the colonialization in the West Bank in return for withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, and he got it. His plan, which passed in Israel for a consensual peace plan, was at first rejected by the Americans as unproductive (the rest of the world condemned it in stronger terms). The Israelis, however, hoped that the similarities between the American and British conduct in Iraq and Israel’s policies in Palestine would lead the United States to change its position, and they were right. It is noteworthy that, until the very last moment, Washington hesitated before giving Sharon the green light for the withdrawal from Gaza. On April 13, 2004, a bizarre scene unfolded on the tarmac of Ben-Gurion airport.

The prime minister’s jet remained stationary for a few hours after its scheduled departure. Inside, Sharon had refused to allow it to take off for Washington until he got US approval for his new so-called disengagement plan. President Bush supported the disengagement per se. What his advisors found hard to digest was the letter Sharon had asked Bush to sign as part of the US endorsement. It included an American promise not to pressure Israel in the future about progress in the peace process, and to exclude the right of return from any future negotiations. Sharon convinced Bush’s aides that he would not be able to unite the Israeli public behind his disengagement program without American support. [23]

In the past, it had usually taken a while for US officials to submit to Israeli politicians’ need for a consensus. This time, it took only three hours. We now know that there was another reason for Sharon’s sense of urgency: he knew that he was being investigated by the police on serious charges of corruption, and he needed to persuade the Israeli public to trust him in the face of a pending court case. “The wider the investigation, the wider the disengagement,” said the left-wing member of Knesset Yossi Sarid, referring to the linkage between Sharon’s troubles in court and his commitment to the withdrawal. [24] It ought to have taken “the US

administration much longer than it did to reach a decision. In essence, Sharon was asking President Bush to forgo almost every commitment the Americans had made over Palestine. The plan offered an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza and the closure of the handful of settlements there, as well as several others in the West Bank, in return for the annexation of the majority of the West Bank settlements to Israel. The Americans also knew all too well how another crucial piece fitted into this puzzle. For Sharon, the annexation of those parts of the West Bank he coveted could only be executed with the completion of the wall Israel had begun building in 2003, bisecting the Palestinian parts of the West Bank. He had not anticipated the international objection—the wall became the most iconic symbol of the occupation, to the extent that the international court of justice ruled that it constituted a human rights violation. Time will tell whether or not this was a meaningful landmark. [25]

As Sharon waited in his jet, Washington gave its support to a scheme that left most of the West Bank in Israeli hands and all of the refugees in exile—and gave its tacit agreement to the wall. Sharon chose the ideal US president as a potential ally for his new plans. President George W. Bush was heavily influenced by Christian Zionists, and maybe even shared their view that the presence of the Jews in the Holy Land was part of the fulfilment of a doomsday scenario that might inaugurate the Second Coming of Christ. Bush’s more secular neocon advisers had been impressed by the war against Hamas, which accompanied Israel’s promises of eviction and peace. The seemingly successful Israeli operations—mostly the targeted assassinations in 2004—were a proof by proxy that America’s own “war against terror” was bound to triumph. In truth, Israel’s “success” was a cynical distortion of the facts on the ground. The relative decline in Palestinian guerrilla and terror activity was achieved by curfews and closures and by confining more than 2 million people in their homes without work or food for protracted periods of time. Even neoconservatives should have been able to grasp that this was not going to provide a long-term solution to the hostility and violence provoked by an occupying power, whether in Iraq or Palestine.

Sharon’s plan was approved by Bush’s spin doctors, who were able to present it as another step towards peace and use it as a distraction from the growing debacle in Iraq. It was probably also acceptable to more even-handed advisers, who were so desperate to see some progress that they persuaded themselves that the plan offered a chance for peace and a better future. These people long ago forgot how to distinguish between the mesmerizing power of language and the reality it purports to describe. As long as the plan contained the magic term “withdrawal,” it was seen as essentially a good thing even by some usually cool-headed journalists in the United States, by the leaders of the Israeli Labor party (bent on joining Sharon’s government in the name of the sacred consensus), and by the newly elected leader of the Israeli left party, Meretz, Yossi Beilin. [26]

By the end of 2004, Sharon knew he had no reason to fear outside pressure. The governments of Europe and the United States were unwilling or unable to stop the occupation and prevent the further destruction of the Palestinians. Those Israelis who were willing to take part in anti-occupation movements were outnumbered and demoralized in the face of the new consensus. It is not surprising that, around that time, civil societies in Europe and in the United States woke up to the possibility of playing a major role in the conflict and were galvanized around the idea of the Boycott, Divestments and Sanctions movement. Quite a few organizations, unions, and individuals were committed to a new public effort, vowing to do all they could to make the Israelis understand that policies such as Sharon’s came at a price.

Since then, from the academic boycott to economic sanctions, every possible means has been attempted in the West. The message at home was also clear: their governments were no less responsible than Israel for the past, present, and future catastrophes of the Palestinian people. The BDS movement demanded a new policy to counter Sharon’s unilateral strategy, not only for moral or historical reasons, but also for the sake of the West’s security and even survival. As the violence since the events of September 11, 2001 has so painfully shown, the Palestine conflict undermined the multicultural fabric of Western society, as it pushed the United States and the Muslim world further and further apart and into a nightmarish relationship. Putting pressure on Israel seemed a small price to pay for the sake of global peace, regional stability, and reconciliation in Palestine.

Thus, the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza was not part of a peace plan. According to the official narrative it was a gesture of peace that the ungrateful Palestinians responded to first by electing Hamas, and then by launching missiles into Israel. Ergo, there was no point or wisdom in any further withdrawal from any occupied Palestinian territory. All Israel could do was defend itself. Moreover, the “trauma” that “nearly led to a civil war” was meant to persuade Israeli society that it is not an episode worth repeating.

Myth #3—Was the War on Gaza a War of Self-Defense?

Although I have coauthored a book (with Noam Chomsky) under the title The War on Gaza, I am not sure that “war” is the right term to describe what happened in the various Israeli assaults on the Strip, beginning in 2006. In fact, after the onset of Operation Cast Lead in 2009, I have opted to call the Israeli policy an incremental genocide. I hesitated before using this highly charged term, and yet cannot find another to accurately describe what happened. Since the responses I received, among others from some leading human rights activists, indicated that a certain unease accompanies such usage of the term, I was inclined to rethink it for a while, but came back to employing it recently with an even stronger conviction: it is the only appropriate way of describing what the Israeli army has been doing in the Gaza Strip since 2006.

On December 28, 2006, the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem published its annual report on the atrocities in the occupied territories. In that year Israeli forces killed 660 citizens, more than triple that of the previous year when around 200 Palestinians were killed. According to B’Tselem, in 2006, 141 children were among the dead. Most of the casualties were from the Gaza Strip, where the Israeli forces demolished almost 300 houses and crushed entire families. This means that since 2000, almost 4,000 Palestinians have been killed by Israeli forces, half of them children; more than 20,000 were wounded. [27]

B’Tselem is a conservative organization, and the numbers of the dead and injured may be higher. However, the issue is not just about the escalating intentional killing, it is about the strategy behind such acts. Throughout the last decade, Israeli policy makers faced two very different realities in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. In the former, they were closer than ever to completing the construction of their eastern border. The internal ideological debate was over, and the master plan for annexing half of the West Bank was being implemented at an escalating pace. The last phase was delayed due to the promises made by Israel, under the terms of the Road Map, not to build any new settlements. But the policy makers quickly found two ways of circumventing this alleged prohibition. First they redefined a third of the West Bank as part of Greater Jerusalem, which allowed them to build towns and community centers within this new annexed area. Secondly, they expanded old settlements to such proportions that there was no need to build new ones.

Overall, the settlements, the army bases, the roads, and the wall put Israel into a po

sition to officially annex almost half of the West Bank whenever it deemed it necessary. Within these territories there were a considerable number of Palestinians, against whom the Israeli authorities would continue to implement slow and creeping transfer policies. This was too boring a subject for the Western media to bother with, and too elusive for human rights organizations to make a general point about them. There was no rush as far as the Israelis were concerned—they had the upper hand: the daily abuse and dehumanization exercised by the dual mechanism of the army and the bureaucracy was as effective as ever in contributing to the dispossession process

Sharon’s strategic thinking was accepted by everyone who joined his last government, as well has his successor Ehud Olmert. Sharon even left the Likud and founded a centrist party, Kadima, that reflected this consensus on the policy towards the occupied territories. [28] On the other hand, neither Sharon nor anyone who followed him could offer a clear Israeli strategy vis-à-vis the Gaza Strip. In the eyes of the Israelis, the Strip is a very different geopolitical entity to that of the West Bank. It remains in the hands of Hamas, while the Palestinian Authority seems to run the fragmented West Bank with Israeli and American blessing. There is no chunk of land in the Strip that Israel covets and there is no hinterland, like Jordan, into which it can expel the Palestinians. Ethnic cleansing as the means to a solution is ineffective here.

The earliest strategy adopted in the Strip was the ghettoization of the Palestinians, but this was not working. The besieged community expressed its will to life by firing primitive missiles into Israel. The next attack on this community was often even more horrific and barbaric. On September 12, 2005, Israeli forces left the Gaza Strip. Simultaneously, the Israeli army invaded the town of Tul-Karim, made arrests on a massive scale, especially activists of the Islamic Jihad, an ally of Hamas, and killed a few of its people. The organization launched nine missiles that killed no one. Israel responded with Operation “First Rain.” [29] It is worth dwelling for a moment on the nature of that operation. Inspired by punitive measures adopted first by colonialist powers, then by dictatorships, against rebellious imprisoned or banished communities, “First Rain” began with supersonic jets flying over Gaza to terrorize the entire population. This was followed by the heavy bombardment of vast areas from sea, sky, and land. The logic, the Israeli army spokespersons explained, was to build up a pressure that would weaken the community’s support for the rocket launchers. [30] As was to be expected, not least by the Israelis, the operation only increased the support for the fighters and gave extra impetus to their next attempt. The real purpose of that particular operation was experimental. The Israeli generals wanted to know how such operations might be received at home, in the region generally, and in the wider world. When the international condemnation proved to be very limited and short-lived, they were satisfied with the result.

“Since “First Rain” all subsequent operations have followed a similar pattern. The difference has been in their escalation: more firepower, more causalities, and more collateral damage, and, as expected, more Qassam missiles in response. Another dimension was added after 2006 when the Israelis employed the more sinister means of imposing a tight siege on the people of the Strip through boycott and blockade. The capturing of the IDF soldier, Gilad Shalit, in June 2006 did not change the balance of power between Hamas and Israel, but it nonetheless provided an opportunity for the Israelis to escalate even further their tactical and allegedly punitive missions. After all, there was no strategic clarity over what to do beyond continuing with the endless cycle of punitive actions.

The Israelis also continued to give absurd, indeed sinister, names to their operations. “First Rain” was succeeded by “Summer Rains,” the name given to the punitive operations that began in June 2006. “Summer Rains” brought a novel component: a land invasion into parts of the Gaza Strip. This enabled the army to kill citizens even more effectively and to present this as a consequence of heavy fighting within dense populated areas; that is, as an inevitable result of the circumstances rather than of Israeli policy. With the end of the summer came operation “Autumn Clouds,” which was even more efficient: on November 1, 2006, seventy civilians were killed in less than forty-eight hours. By the end of that month, almost 200 had been killed, half of them children and women. Some of this activity ran in parallel to the Israeli attacks on Lebanon, making it easier to complete these operations without much external attention, let alone criticism

From “First Rain” to “Autumn Clouds” one can see escalation in every area. Firstly, there was the disappearance of the distinction between “civilian” and “non-civilian” targets: the senseless killing had turned the population at large into the main target of the operation. Secondly, there was the escalation in the employment of every possible killing machine the Israeli army possesses. Thirdly, there was the conspicuous rise in the number of casualties. Finally, and most importantly, the operations gradually crystallized into a strategy, indicating the way Israel intends to solve the problem of the Gaza Strip in the future: through a measured genocidal policy. The people of the Strip, however, continued to resist. This led to further genocidal Israeli operations, but still today a failure to reoccupy the region.

In 2008, the “Summer” and the “Autumn” operations were succeeded by operation “Hot Winter.” As anticipated, the new round of attacks caused even more civilian deaths, more than 100 in the Gaza Strip, which was bombarded once more from air, sea, and land, and also invaded. This time at least, it seemed for a moment that the international community was paying attention. The EU and the UN condemned Israel for its “disproportionate use of force,” and accused it of violating international law; the American criticism was “balanced.” However, it was enough to lead to a ceasefire, one of many, that would occasionally be violated by another Israeli attack. [31] Hamas was willing to prolong the ceasefire, and authorized the strategy in religious terms, calling it tahadiah—meaning a lull in Arabic, and ideologically a very long period of peace. It also succeeded in convincing most factions to stop launching rockets into Israel. Mark Regev, the Israeli government spokesperson, admitted as much himself. [32]

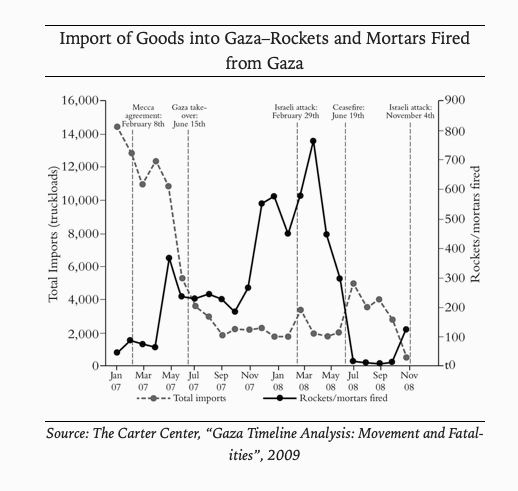

The success of the ceasefire might have been assured had there been a genuine easing of the Israeli siege. Practically this meant increasing the amount of goods allowed into the Strip and easing the movement of people in and out. Yet Israel did not comply with its promises in this regard. Israeli officials were very candid when they told their US counterparts that the plan was to keep the Gaza economy “on the brink of collapse.” [33] There was a direct correlation between the intensity of the siege and the intensity of the rocket launches into Israel, as the accompanying diagram prepared by the Carter Peace Center illustrates so well.

Israel broke the ceasefire on November 4, 2008, on the pretext that it had exposed a tunnel excavated by Hamas—planned, so they claimed, for another abduction operation. Hamas had been building tunnels out of the Gaza ghetto in order to bring in food, move people out, and indeed as part of its resistance strategy. Using a tunnel as a pretext for violating the ceasefire would be akin to a Hamas decision to violate it because Israel has military bases near the border. Hamas officials claimed that tunnel in question had been built for defensive reasons. They never shied away from boasting about a different function in other cases, so this might be true. The Irish Palestine solidarity group Sadaka published a very detailed report compiling evidence showing that Israeli officers knew there was no danger whatsoever from the tunnel. The government just needed a pretext for yet another attempt to destroy Hamas. [34]

Hamas responded to the Israeli assault with a barrage of missiles that injured no one and killed no one. Israel stopped its attack for a short period, demanding that Hamas agree to a ceasefire under its conditions. Hamas’s refusal led to the infamous “Cast Lead” operation at the end of 2008 (the code names were now changed to even more ominous ones). The preliminary bombardment this time was unprecedented—it reminded many of the carpet bombing of Iraq in 2003. The main target was the civilian infrastructure; nothing was spared—hospitals, schools, mosques—everything was hit and destroyed. Hamas responded by launching missiles into Israeli towns not targeted before, such as Beersheba and Ashdod. There were a few civilian casualties, but most of the Israelis killed, thirteen in total, were soldiers killed by friendly fire. In sharp contrast, 1,500 Palestinians lost their lives in the operation. [35]

A new cynical dimension was now added: international and Arab donors promised aid running into the billions to rebuild what Israel would only destroy again in the future. Even the worst disaster can be profitable.

The next round came in 2012 with two operations: “Returning Echo,” which was smaller in comparison to the previous attacks, and the more significant “Pillar of Defense” in July 2012, which brought an end to the social protest movement of that summer, with its potential to bring down the government for the failure of its economic and social policies. There is nothing like a war in the south to convince young Israelis to stop protesting and go out and defend the homeland. It had worked before, and it worked this time as well.

In 2012, Hamas reached Tel Aviv for the first time—with missiles that caused little damage and no casualties. Meanwhile, with the familiar imbalance, 200 Palestinians were killed, including tens of children. This was not a bad year for Israel. The exhausted EU and US governments did not even condemn the 2012 attacks; in fact they repeatedly invoked “Israel’s right to defend itself.” No wonder that two years later the Israelis understood that they could go even further. Operation “Protective Edge,” in the summer of 2014, had been in the planning for two years; the abduction and killing of three settlers in the West Bank provided the pretext for its execution, during which 2,200 Palestinians were killed. Israel itself was paralyzed for a while, as Hamas’s rockets even reached Ben-Gurion airport.

For the first time, the Israeli army fought face to face with the Palestinian guerrillas in the Strip, and lost sixty-six soldiers in the process. In this battle between desperate Palestinians, their backs to their wall, enraged by a long and cruel siege, and the Israeli army, the former had the upper hand. The situation was like that of a police force entering a maximum security prison it had controlled mainly from outside, only to be faced with the desperation and resilience of prisoners who have been systematically starved and strangulated. It is frightening to think what Israel’s operational conclusions will be after this clash with brave Hamas fighters.

The war in Syria and the resulting refugee crisis did not leave much space for international action or interest in Gaza. However, it seems everything is poised for yet another round of attacks against the people of the Strip. The UN has predicted that, at the current rate of destruction, by 2020 the Strip will have become uninhabitable. This will be brought about not only by military force but also by what the UN calls “de-development”—a process whereby development is reversed:

Three Israeli military operations in the past six years, in addition to eight years of economic blockade, have ravaged the already debilitated infrastructure of Gaza, shattered its productive base, left no time for meaningful reconstruction or economic recovery and impoverished the Palestinian population in Gaza, rendering their economic wellbeing worse than the level of two decades previous.

This death sentence has become even more likely since the military coup in Egypt. The new regime there has now closed the only opening Gaza had outside of Israel. Since 2010, civil society organizations have sent flotillas to show solidarity and break the siege. One of them was viciously attacked by Israeli commandoes, who killed nine of the passengers on board the Mavi Marmara and arrested the others. Other flotillas were treated better. However, the 2020 prospect is still there, and it seems that to prevent this infliction of a slow death the people of Gaza will need more than peaceful flotillas to persuade the Israelis to relent.

Endnotes

1. Ilan Pappe, “The Loner Desparado: Oppression, Nationalism and Islam in Occupied Palestine,” in Marco Demchiles (ed.), A Struggle to Define a Nation (forthcoming with Gorgias Press).

2. Pappe, The Idea of Israel, pp. 27–47.

3. Ibid, pp. 153–78.

4. A refreshing view on Hamas can be found in Sara Roy, Hamas and Civil Society in Gaza: Engaging the Islamist Social Sector, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

5. Yehuda Lukacs, Israel, Jordan, and the Peace Process, Albany: Syracuse University Press, 1999, p. 141.

6. Quoted in Andrew Higgins, “How Israel Helped to Spawn Hamas,” Wall Street Journal, January 24, 2009.

7. Shlomi Eldar, To Know the Hamas, Tel Aviv: Keter, 2012 (Hebrew).

8. Ishaan Tharoor, “How Israel Helped to Create Hamas,” Washington Post, July 30, 2014.

9. Chabon in an interview with Haaretz, April 25, 2016.

10. For a good analysis of how Netanyahu employs the “clash of civilizations” by a university student, see Joshua R. Fattal, “Israel vs. Hamas: A Clash of Civilizations?,” The World Post, August 22, 2014, at huffingtonpost.com.

11. “Hamas Accuses Fatah over Attack,” Al Jazeera, December 15, 2006.

12. Ibrahim Razzaq, “Reporter’s Family was Caught in the Gunfire,” Boston Globe, May 17, 2007—one of many eyewitness accounts of those difficult days.

13. “Palestine Papers: UK’s MI6 ‘tried to weaken Hamas,'” BBC News, January 25, 2011, at bbc.co.uk.

14. Ian Black, “Palestine Papers Reveal MI6 Drew up Plan for Crackdown on Hamas,” Guardian, January 25, 2011.

15. A taste of his views can be found in Yuval Steinitz, “How Palestinian Hate Prevents Peace,” New York Times, October 15, 2013.

16. Reshet […]

17. Benny Morris, Channel One, April 18, 2004, and see Joel Beinin, “No More Tears: Benny Morris and the Road Back from Liberal Zionism,” MERIP, 230 (Spring 2004).

18. Pappe, “Revisiting 1967.”

19. Ari Shavit, “PM Aide: Gaza Plan Aims to Freeze the Peace Process,” Haaretz, October 6, 2004.

20. Haaretz, April 17, 2004.

21. Pappe, Revisiting 1967.

22. For an excellent analysis written on the day itself, see Ali Abunimah, “Why All the Fuss About the Bush–Sharon Meeting,” Electronic Intifada, April 14, 2014.

23. Quoted in Yediot Ahronoth, April 22, 2014.

24. See “Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,” on the ICJ website, icj-cij.org.

25. At first, in March 2004, Beilin was against the disengagement, but from July 2004 he openly supported it (Channel One interview, July 4, 2004).

26. See the fatalities statistics on B’Tselem’s website, btselem.org.

27. Leslie Susser, “The Rise and Fall of the Kadima Party,” Jerusalem Post, August 8, 2012.

28. John Dugard, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of the Human Rights in the Palestinian Territories Occupied by Israel since 1967, UN Commission on Human Rights, Geneva, March 3, 2005.

29. See the analysis by Roni Sofer in Ma’ariv, September 27, 2005.

30. Anne Penketh, “US and Arab States Clash at the UN Security Council,” Independent, March 3, 2008.

31. David Morrison, The Israel-Hamas Ceasefire, Sadaka, 2nd edition, March 2010, at web.archive.org.

32. “WikiLeaks: Israel Aimed to Keep Gaza Economy on the Brink of Collapse,” Reuters, January 5, 2011.

33. Morrison, The Israel-Hamas Ceasefire.

34. See the B’Tselem report “Fatalities during Operation Cast Lead,” at btselem.org.

35. “Gaza Could Become Uninhabitable in Less Than Five Years Due to Ongoing ‘De-development’,” UN News Centre, September 1, 2015, at un.org.”