When political ambition meets the built space, what happens when the state falters? In Iraq, buildings don’t simply reflect ideology — they absorb it, transmit it, and sometimes resist it. Especially when left unfinished. Baghdad’s Al-Rahman Mosque embodies the enduring tension between architecture, power, and collective memory.

Meriam Othman

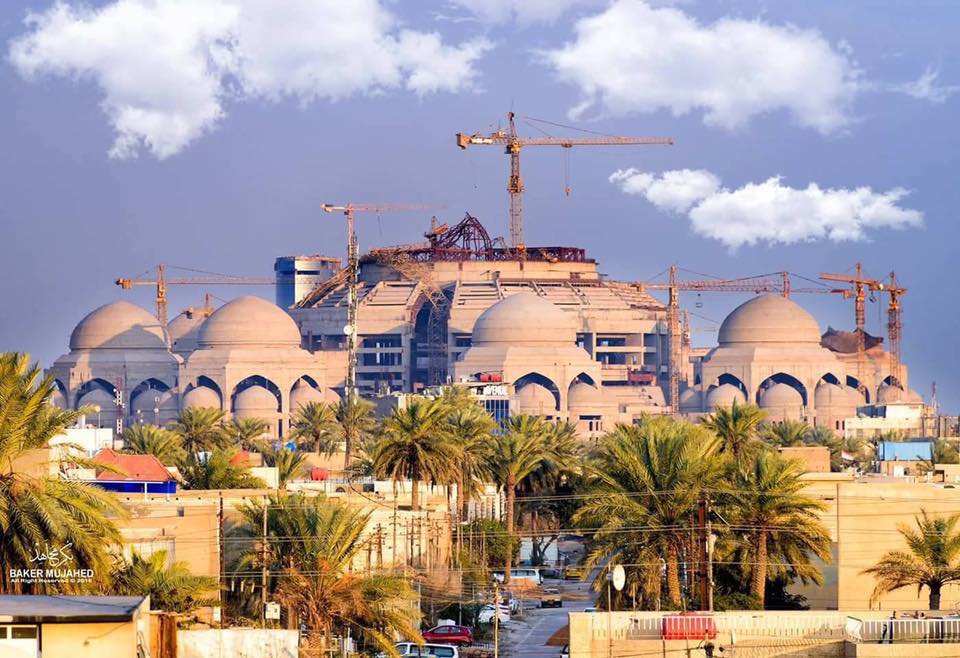

On the road to the Iraqi parliament, just beyond Baghdad’s administrative core, there is a structure that interrupts the skyline. I passed it almost daily, traveling from the Green Zone to the parliament complex for meetings. Each time we turned that corner, I found myself staring. Al-Rahman Mosque always emerged at the same point in the drive: suspended, silent, immense. A vast concrete form, it seemed to hover just outside the routines of the city, more presence than place.

From a distance, it looked less like a construction site than a question hanging over Baghdad. I never saw a single worker, not even a guard. Just cranes, frozen mid-lift, paused in a gesture that had long outlived the politics that placed them there. Still, I assumed for a long time that the mosque was simply unfinished. Its scale was too ambitious, its machinery too present, for anything else to be true — or so I thought.

One afternoon, during one of our regular drives, I turned to a security officer driving us to parliament, a native Baghdadi who had grown up in the very neighborhood where the mosque stood. I asked him when it might be completed. He didn’t answer right away. Then, with a dry laugh and a shake of the head, he said, “No one’s touched it in 20 years.”

There was no irony in his voice, only a kind of exhausted familiarity, like someone repeating a story too old to surprise anyone. The silence that followed felt almost theatrical, as if staged by the building itself. That was the moment the mosque shifted for me, from a construction site to something stranger.

Commissioned by Saddam Hussein in the late 1990s, Al-Rahman Mosque was intended to accommodate over 15,000 worshippers. It was to be one of the largest mosques in the world, built on the site of Baghdad’s old racetrack. A central dome, surrounded by cascading sets of smaller domes, would have shimmered with gold-decorated faience, an architectural composition meant to rival the Taj Mahal.

But the project stalled. The 2003 U.S.-led invasion froze the structure in place. The cranes still stand, unmoved. The domes remain unclosed. The mosque was never finished. Perhaps it never will be.

That daily encounter became something I began to anticipate. The mosque entered my imagination not as a place of worship, or even as a failed project, but as a kind of anchor — a spatial interruption that seemed to speak more about Iraq’s political and architectural memory than any meeting I was headed to.

Architecture without closure

We are used to thinking of buildings as testaments to power. Dictators build monuments to themselves; states rebrand skylines to signal stability; capitals are redesigned to perform legitimacy. But what do we make of buildings that were never finished? What happens when an architectural assertion of power is interrupted but not erased?

The relationship between politics and architecture in Iraq has, at many key moments, shaped the physical and symbolic form of its cities. From Baghdad to Karbala to Al-Najaf, urban transformation has often mirrored the shifting demands of political authority. In Al-Najaf’s Old City, for example, successive governments reconfigured the urban and architectural fabric in ways that altered not just the city’s form but its spiritual texture: architecture as theology, restructured through state intervention. In Iraq, buildings don’t simply reflect ideology — they absorb it, transmit it, and sometimes resist it. Especially when left unfinished.

There is a tendency, especially in outside interpretations, to read unfinished architecture as a sign of political failure or collapse. But this perspective assumes history follows linear paths of progress, resolution, and repair. Iraq’s urban landscape resists such framing. Baghdad itself bears the imprint of centuries of invasion and reconstruction, from the Mongol invasion in 1258 to the violence and occupation of the modern era, not as a city rebuilt from ruins, but as one continuously reassembled through shifting regimes, ideologies, and ambitions. The mosque is evidence of an architectural expression of how transformation unfolds in fragments, contradictions, and deferrals. Its very incompleteness absorbed the weight of Iraq’s shifting narratives without ever offering resolution.

The inheritance of incompletion

Al-Rahman Mosque was conceived during Saddam’s “Faith Campaign,” a strategic return to Islamic rhetoric in the 1990s where religious language was co-opted to shore up political legitimacy. Mosques were commissioned across Iraq as state-led expressions of Islamic modernity. Al-Rahman was meant to be the crown jewel.

But its legacy was never singular. After the fall of the regime, the site passed through multiple hands: taken over by armed groups aligned with Shi’a political factions, informally occupied by displaced families, and eventually claimed by the Shi’a Endowment Office amid legal disputes. Control of the site became a proxy for larger sectarian and political contests over Iraq’s religious landscape.

To complete the structure now would not simply be to build a mosque. It would mean choosing a narrative, taking a position in Iraq’s contested post-2003 identity. That makes it politically radioactive. Its very existence is a remnant of a state-led project to fuse religious authority with political spectacle; and in failing to meet Saddam’s vaulting ambition, it stands as a monument both suffused with meaning yet aching for purpose.

Rather than allowing the site to remain as a painful reminder of Iraq’s authoritarian past or a proxy in sectarian power games, it could be repurposed as a civic space that serves the everyday needs of Baghdadis. Not a shrine, nor a utopian gesture, but a public, useful, and open space where history is neither glorified nor erased — only inhabited. As someone who encountered it daily from the outside, I kept wondering what it could become if freed from the meanings imposed on it. Architecture can carry history without being trapped by it. What would it mean for Iraq to claim this site not through consensus but through imagination?

This isn’t to suggest that a building alone can overcome the complex legacies of sectarian violence or political fragmentation. In Iraq, space has often been a proxy for power, claimed, renamed, and restricted along lines of identity. Any attempt to reconceive a site like Al-Rahman Mosque would need to reckon with that history, not erase it. But perhaps that’s the point: not to pretend the divisions never existed, but to create a space where no single narrative dominates. Architecture may not heal divisions, but it can hold them — giving form to complexity.

Reclaiming or refusing?

There have been gestures: judicial rulings, compensation orders, even talk of a unified Sunni-Shi’a space. But nothing has materialized. The site remains suspended, not because no one can build, but because no one can agree on what building would mean. And even if a shared vision were reached, the central government’s limited capacity, financial, administrative, and logistical, makes large-scale intervention difficult to realize. The longer it remains undecided, the more it reveals how architecture in Iraq continues to be a site of tension and latent invention.

I often imagined what it would be like to enter the mosque, not as a worshiper but as a citizen. Could its massive halls become spaces for public gathering, for libraries, for shade and silence? Could its scale be given back to the people who live in its shadow?

Architecture is not neutral material. The political intent of the original design, its scale, its symbolism, its location, cannot be separated from the circumstances of its origin. To finish it today would require not just physical labor, but a re-articulation of Iraq’s collective narrative. That is something the current state apparatus, fractured and decentralized, is not yet equipped to deliver.

A structure in suspension

Baghdad is not a city of ruins, as it is often miscast. It is a city marked by interruption — where structures outlive the regimes that built them and unfinished projects become part of the urban landscape. These are not relics of failure; they are reminders of how history settles into the built environment without ceremony.

Al-Rahman Mosque stands not as a wound but as a witness. Some buildings are left unfinished by chance. Others, by design. And some, like this one, because their meaning remains unresolved. Walk long enough around Al-Rahman and that uncertainty becomes visible. The symmetry of its domes suggests purpose, but the rusted cranes say otherwise. It isn’t abandoned, but it isn’t active either. It holds form without function — presence without clarity.

The question now is not whether to finish it, but whether we can reimagine it honestly, locally, practically. Not as a grand monument, but as a space shaped by the city that has grown around it. That decision, like the structure itself, is still waiting.