In Waking Up to My Distorted City, a bilingual book with essays and photographs, Hisham Bustani attempts to explore his ambiguous relationship with his hometown Amman and his obsessive attachment to the city’s past, reconstructing it through memories of his childhood and adolescence, as well as the recollections of his father and aunt, all coalescing into a lens through which the city’s current crisis can be read. Linda Al Khoury’s photos in My Distorted City reflect the urban transformations that occurred in Amman during the period when her spatial memory was forming. Through visual storytelling, Linda’s photographs document the rapid and disorganized changes that were inflicted on the city. The two of them combined their projects under one title, Waking Up to My Distorted City, which celebrated its launch last month in Amman, Jordan.

The Markaz Review: Where did the idea for the book morph from?

Hisham Bustani: The idea for the book came from a contradictory relationship I have with Amman; on one hand, I have this deep connection and love for this city, that stems from my own childhood and teenage memories, but also from my father’s and aunt’s memories — both born in Amman in 1937 and 1919, respectively. My own childhood-teenage memories construct the city as a playground, a non-restricted free space, something that you own and feel free to roam and participate in. My father’s and aunt’s memories construct the city as something intimate, something you are born into, and carry with you as a personal and collective history. It also portrays an Amman that was, one characterized by social diversity and closely-knit neighborhoods of one-story limestone houses, a city as it was before its Sayl (river) was “assassinated,” buried under a concrete ceiling, its waters redirected into especially-built underground canals, on top of which a street has emerged from allowing the concrete and the black asphalt to rise and grow over the ground. Aptly, the area is now known as Saqf al-Sayl, “the river’s ceiling.” On the other side, there’s a relationship of bitterness, alienation, restriction, which all comes from a later adult interaction with the city and its ruling authority, when a critical perspective replaced childhood’s innocence. There was (and still is) an authoritarian intervention to exclude me and what I represent, sometimes by force (the latest episode: banning the launch of one of my books in 2021). The “open playground” of my childhood has turned into an ever-constricting prison cell whose walls I must fight and continually push back against to maintain my own space and place within it. The book is one aspect of that fight.

LINDA AL KHOURY: In 2015 there was a proposal for a project called Tashbeek, a collaboration and networking project that twinned artists from different creative fields to present a collaborative piece of work. When Hisham and I decided to participate in Tashbeek, I had already started to work on my city project and discussing it with Hisham, the idea for a book was born. This book is important because it opens people’s eyes to the distortion that is happening to their city right before their eyes, a distortion that is isolating the inhabitants so that they feel exiled at home, far removed from the decision-making process, their city’s lands up for sale for the highest buyer.

TMR: Let’s talk about the book’s title, what constitutes a “distorted” city?

HISHAM BUSTANI: The book’s title is a combination of two project titles (my texts and Linda’s photography) that are separate yet united in their theme and the cover that binds them. Even the choice of pages (80gm bulky yellowish paper for the texts, 150gm photo-quality matt paper for the photographs) stresses this separation since the projects are intended to be taken in as complete bodies of work that are in discussion with each other, each adding additional perspectives to the other, opening new angles for a reader. The overall title of the book is Waking Up to My Distorted City. Linda’s project is titled: My Distorted City; while mine carries the title of Waking Up to My City, which also contains a gloomy element of a continuous, daily revelation(s) to a never-ending transformation of Amman, and, as I explained in the answer of the first question, the ever-constricting walls that define my space (and place) within it. This is the kind of distortion that I engage with, a distortion between the inhabitants of Amman and the relational meaning of their city to them, and to me. It is peculiar, from this angle, to note that Linda’s photographs have not a single human in any of them. This perfectly reflects the distortion I explore in my texts and shows how the two projects engage and complement each other.

LINDA AL KHOURY: The book’s title created quite a buzz when it was released. Some readers objected to the use of the word “distortion” to describe the city of Amman. They found it harsh and even cruel. But I disagree with all of them. I am, by nature, a very visual person and rely very heavily on my spatial memory to get me from point A to point B. I have an acute sense of place and space and can remember minute details of a place from one visit. That said, I am very quick to pick up any change to my surroundings — whether it’s the demolition of a building or uprooting of a single shrub, you bet I’ll notice it. As a child, I was allowed to roam the streets of Amman very freely. Twenty years ago, I was one of quite possibly a handful of people to cycle around the city. This intimate interaction with the old city bound me to it and as I investigated its alleys, staircases, and streets, I was absorbing all the details into my memory. What I’m trying to say is that my spatial memory itself was shaped by all the places that I discovered and experienced, particularly Jabal Amman and Rainbow Street in particular, where my grandmother’s house was located in addition to my school and school friends’ houses, the church and the community center where I practiced Taekwondo.

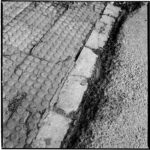

That’s why when the municipality began introducing the first changes to Rainbow Street, by overlaying the concrete with cobblestones to change it to a pedestrian area, not only did it feel like a distortion to the place, but it also felt like a personal violent erasure of my spatial memory. Worse, the erasure appeared to be sporadic, without rhyme or reason. A defacing, mutilation, of the city that contradicted its culture and urban character was taking place right before my eyes and it was only a matter of time before these projects proved flawed and were stopped. Sadly, this was happening all around the city. There are countless projects that pop up now under the guise of modernity that have no place within the culture of the place.

TMR: What were the key morphological shifts/distortions that Linda and yourself wanted to highlight in the book?

HISHAM BUSTANI: I am interested in the socio-morphology of Amman. How spaces and places were used and felt as communal, collective, interactive spaces, and how that changed over time through authoritarian and neoliberal interventions designed to alienate and push people into separate, isolated emotional-physical enclaves. Take Daraj Far’oun (the popular name then for the Roman Theater, located in the heart of the city), which was a collective space for communal celebrations. My aunt and father tell stories about how Amman would gather there to interact, play and mark the Eid festivities. Now, it’s a closed, controlled “archeological” site with the surrounding spaces and plazas fenced in. A police patrol car is stationed at each one of its three entrances. This besiegement signals that the people of Amman no longer own their space and time.

The Sayl is another major socio-morphological change. Amman was historically called “the city of waters,” and the water still lives on in toponyms like Ras al-’Ein (the spring’s head, its starting point) and Saqf al-Sayl, which has now transformed into a concrete and asphalt monstrosity. The water was part of Amman’s everyday life: our family received their water supply from a spring that poured into the Sayl situated next to their home, where my father learned to swim. Every day, and on foot, he crossed the bridge to get to school and back, and later again to reach his father’s shop in Talal Street before making his way back home again. Furthermore, my grandfather convened with other merchants from the souq at the end of each working day at al-Manshiyya coffee house, which was set up along the Sayl’s bank. As such, the Sayl was the symbol of the city’s closeness, its communal embrace. Its assembling magnet. By “assassinating” it, they condemned the city to fragmentation.

LINDA AL KHOURY: My collection of photographs reflects the incoherent transformations in light of these various distortions inflicted on my city. This proliferation of unstructured and random city planning is a distortion. For example, take the area of the 3rd circle. This was once a quiet suburban neighborhood, known for its villas that were built between the 20s and 50s. It has now been transformed into a chaotic and traffic-congested area due to municipal permits allowing for the construction of several storied hospitals in this tight residential area. Once there was no more land to build on, they allowed permits that stripped down the old villas in order to convert them to offices or even to demolish them entirely to allow for glass towers in their place. Stripped of most of the trees, it now looks ugly and grotesque. The area has become so crowded now and bears no resemblance to Amman’s beautiful stone architecture that it is famous for. Even the hilly skyline that was Amman’s key feature is no longer what it used to be.

TMR: What do you see as the driving forces behind the distortion of the city of Amman?

HISHAM BUSTANI: There are many factors affecting the transformation of the city, but the main one, the most powerful and significant, is authoritarian intervention. Every ruler of the city demands that history should begin with their arrival, disregarding everything that had come before. This erasure is a key concept in how the authorities deal with Amman. There is no respect for places of historic, social, and architectural significance. Any landmark, of any significance, can be torn down in a second and replaced with a glass-and-steel structure. When an Ammani reads Abdul Rahman Munif’s Story of a City: A Childhood in Amman (trans. Samira Kawar), they are surprised to discover that only a few of the places mentioned in the book remain today. There is no continuity. Even Munif, himself an influential writer in Arabic literature and the author of one of the most important books on Amman, has been erased from the city.

Another factor affecting the city is how it is continuously controlled, designed, and redesigned which has led to a chronic and deepening sense of estrangement for its inhabitants. Building barriers prevents an integration between peoples and places, disallows the communality of a space. Control is a major aspect of contemporary Amman, which is now littered with surveillance cameras, its public plazas fenced or redesigned to include structures that prevent the crowd assemblies. Police are always being deployed to public spaces to set up wire or concrete fences locking in the area, and putting an end to any form of civil protest. Otherwise, many less threatening communal spaces are left to rot and look like a dump — a case in point is Amman’s staircases (characteristic of Amman’s hilly topography) which are heavily littered with garbage.

Consumerism and cosmopolitanism — which are not unique to Amman — are destroying not only how the city feels, but how it looks, leaving behind ugly scars in their wake. The two abandoned glass towers on the 6th circle for example, built on what used to be the neighborhood’s park, is a daily reminder of how Amman’s esthetics are ignored, intentionally malformed, and stand as proof that the city’s citizens are insignificant. They don’t count. These towers are a massive insult to Ammanis and Amman, maintained as such to keep people small and humiliated in their city. Abdali’s glass and steel Boulevard is another of these projects, dubbed by its makers “The New Downtown” to replace what people always referred to as Wasat al-Balad — the heart of the city — where water used to flow. Now, this “heart” is besieged with private security on all entrances, preventing non-refined-looking citizens from accessing this sterile, extremely controlled, neoliberal haven.

LINDA AL KHOURY: A lot of Amman’s beautiful old buildings have been demolished to make way for glass towers because they are cheaper to build. I find this grotesque not only because the structures are desolate and devoid of human presence and warmth, but also because in a country like Jordan, a parched nation, maintaining the cleanliness of those windows is a challenging task, which further adds to the distortion and the slovenly appearance of the city. That’s not forgetting the energy expenditure that goes into warming them up in the winter and cooling them down in the summer. But there is also a visual distortion or grotesqueness because of the jarring contrast between the old and the new. There is no harmony in the architectural designs nor in the planning of the city.

TMR: How would you describe this collaboration?

HISHAM BUSTANI: This collaboration between text and photograph was a discussion of themes rather than a molding of forms. It was intended that each artist should work individually and separately, each, exploring their own personal relationship with Amman and its transformations. There was no intention of alignment. On the contrary, we wanted each artistic project (the text collection and the photo album) to stand alone, separate from each other, yet with an obvious and tangible continuity, as each part introduces new layers of understanding and interacting with the other.

The bilingual choice for the project was also a crucial and peculiar aspect of the project. Amman is now full of ajaneb — white migrant laborers who work in international organizations and NGOs, usually with a superficial and limited connection to the city and its citizens, who lock themselves in gentrified “authentic” neighborhoods like Jabal al-Lweibdeh, some never learning a sentence in Arabic during their years-long stay. The book is an attempt to engage those residents in Amman as well to draw their attention to their role in their temporary, transitory city, and their long-term effect on it.

In that regard, I want to commend the work of the excellent literary translators — Addie Leak, Nariman Youssef, Alice Guthrie, Thoraya El-Rayyes, and Maia Tabet — for taking every care to maintain the unique artistic style that I applied in the Arabic text, maintaining intact almost all of the nuances, hidden and dual meanings, in addition to the special local contexts. Nariman and Addie also contributed to the overall editing and proofreading. Thoraya is an Ammani herself, and Addie lived in Amman for a number of years, and is married to an Ammani, and between them, in addition to the wonderful work of Nariman, Alice and Maia, a very specific, and rare, form of biculturality was achieved in the translation.

LINDA AL KHOURY: When we took the decision to publish the book, and were ready to do so, we decided straight away that a bilingual version is important as Hisham said. Another bifold nature is that the book’s creative content targets two audiences, avid photographers and literary intellectuals. We were very excited at trying out this innovative idea of combining the two perspectives in one book. The book should be looked at as two separate books in conversation with each other about a common theme which is the distortion of the city.