The traveling exhibition Portraits of France puts the role of immigrants from all over the world at the center of French history. An overview of an essential historical approach.

Laëtitia Soula

318 names, portraits, faces, regards. They follow one another throughout the panels and have one thing in common: these people of immigrant origin have left their mark on French history.

At a time when the extreme right won more than 13 million votes in the second round of last year’s presidential elections, crossing paths with these Portraits of France is invigorating for the soul. They serve as a reminder that post-war France has yet to elect an extreme rightwing candidate to the Elysées, though that has been a specter ever since Jean-Marie Le Pen brought the Front National party into the national French consciousness. These portraits of immigrants reveal an essential truth about ourselves, which is many of us are the sons and daughters of migrants and nomads, with roots here and there.

The world has never truly been isolationist; crossing borders from one place to the next is in our DNA.

National narrative and collective memory

As a country of human rights, a land of asylum for refugees, and a socialist state when it comes to education and healthcare, France is known for its defense of freedom. For this reason, it is incumbent upon us to recall the contribution of the nation’s immigrant populations, who tend to be left out of the official narrative.

Conceived by the National Museum of Natural History and the Achac research group, Portraits of France began its tour at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris in 2021-2022, passing through Clichy-sous-Bois and Reims, before reaching the site of La Grave in Toulouse in 2023, then Isère. It continues to tour.

The initiative, backed by Macron’s administration, aims to present strong stories, exemplary careers and courageous commitments, giving pride of place to the immigrants the exhibition features so that they become part of our collective memory.

Journey of life

Working on colonial and post-colonial representations, discourses and imaginaries, as well as on migratory flows, the researchers of the Achac group have been able to restore the substance of these life paths. We travel from the French Revolution to the Belle Epoque, from the Great War to the Roaring Twenties, from the Second World War to the end of the colonial empire, from black and white France to the 21st century, encountering the challenges and issues of each of these periods.

The migratory stories continue throughout history, like a national chronicle open to the reality of the world. The commitment is intellectual, cultural, artistic, political, union, military or associative. The duty of memory urges exhibition viewers to recognize the work of these women and men from elsewhere, whose portraits tell us about their genius and their struggles.

Famous, infamous and forgotten names

Among the political women to remember is the Franco-Peruvian Flora Tristan (1803-1844), a figure of social struggle, creator of the newspaper L’Union Ouvrière, one of the mothers of modern feminism. Committed to socialist ideas and against slavery, she wrote a manifesto on “The need to welcome foreign women,” and she decided to flee domestic violence, escaping an assassination attempt by her former spouse, and campaigned for the legalization of divorce.

Belgian politician Anne-Josèphe Théroigne de Méricourt (1762-1817), the only woman in the galleries of the French Assembly during the Revolution in 1789, advocated for the expansion of civil rights. She campaigned for the abolition of slavery, for the right of women to bear arms and to run for office.

Household names include the Polish physicist and chemist Marie Curie (1867-1934), the Romanian writer Tristan Tzara (1896-1963), and the Greek singer, actress and politician Melina Mercouri (1920-1994). The actor Louis de Funès (1914-1983) came from a family of Spanish immigrants, and the painter Pablo Picasso was refused French nationality in 1940.

Austria gave us the actress Romy Schneider (1938-1982) and Italy, the actor and singer Yves Montand (1921-1991), whose real name was Ivo Livi; the writer and cartoonist François Cavanna (1923-2014) and the actor and singer Serge Reggiani (1922-2004).

Born in Argentina, the novelist Joseph Kessel was stateless before obtaining French citizenship. Charles Aznavour (1924-2018), for his part, was born on the road, in exile, to his stateless Armenian parents, who were fleeing the genocide. Born in Tunisia, cartoonist Georges Wolinski (1934-2015), who had a Polish father and a Franco-Italian mother, made his mark on the French press before he was murdered by Islamist terrorists in the 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris.

The dark hours

Some of these stalwarts have built the history of the country in spite of the egregious treatment of a France mired in its dark hours (slavery, wars, colonization, extremism, racism, xenophobia). One thinks of the Senegalese Jean-Baptiste Belley (1750-1805), sold as a slave and forcibly enlisted in the French army: a militant for the abolition of slavery, a little-known figure of the French Revolution, he became the first black deputy in French history.

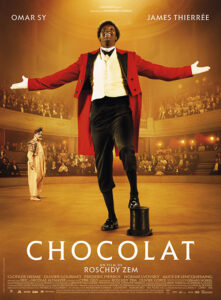

One thinks of the Cuban pantomime actor Rafael Padilla (1867-1917), known by his artist name Chocolat, who was born a slave and ended his life in misery.

There is also the Tunisian human rights activist Saïd Bouziri (1947-2009), who participated in the founding of the Arab Workers Movement. Targeted by the Marcellin-Fontanet circular and an expulsion order because of his activism, he had to go on hunger strike to assert his rights to the French authorities.

One thinks of the fate of the Harkis, the massacre of Italians in Aigues-Mortes in 1893, the Spanish refugees fleeing Franco’s regime at the end of the 1930s, parked in concentration camps, the massacre of Algerians in Paris in October 1961 and the repression in the Charonne metro station in 1962.

One thinks of the swimming champion Alfred Nakache (1915-1983), born in Algeria, victim of the anti-Semitic laws of Vichy. He swam in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin with the French swim team. In the early ‘40s, he was dismissed from his teaching job and stripped of his French citizenship, excluded from swimming competitions because he was Jewish.

Nakache was deported to Auschwitz in 1944 where his wife and two-year-old daughter died. He continued to swim at the concentration camp where he became known as the “swimmer of Auschwitz.” Freed in 1945, he returned to the south of France debilitated from deportation, yet rebuilt himself and began competing again. Renowned for his courage and resilience, Alfred Nakache was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

From Algeria

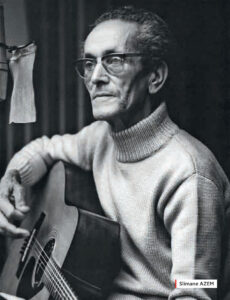

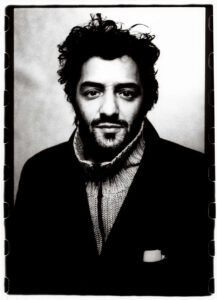

Among these portraits of France, we find the politician Messali Hadj (1898-1974), a figure of Algerian independence, the writer Mouloud Feraoun (1913-1962) murdered by the OAS in Algiers, and Slimane Azem (1918-1983), who sang of exile and love for Algeria. The exhibition includes Franco-Algerian rocker Rachid Taha (1958-2018) of the group Carte de Séjour, who in 1986 gave an Arab accent to Charles Trenet’s “Douce France.” An adept of fusion, mixing rock, punk, raï or chaâbi, he denounced in his songs xenophobia, hatred of the foreigner. His legacy is the Algerian-French singer-songwriter Souad Massi, who continues to write and sing in Arabic, French and Amazigh, enchanting fans worldwide.

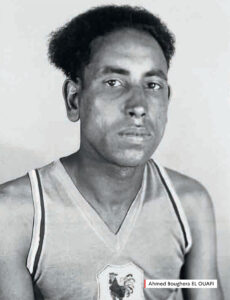

A friend of Pierre Bourdieu, the sociologist Abdelmalek Sayad (1933-1998), nicknamed “the Socrates of Algeria,” gave a human perspective on the history of migration. As for Ahmed Boughera El Ouafi (1898-1959), athlete and worker champion of the marathon of the Olympic Games in Amsterdam in 1928 under the colors of France, he would be forgotten by history and ended his life in misery.

Among the artists and intellectuals from Algeria, we should mention the musician and singer Cheikha Remitti (1923-2006), revered as the queen of raï, who provoked the puritans by tackling themes such as love, alcohol, carnal pleasure, freedom or feminism.

Novelist Assia Djebar (1936-2015), pen name of Fatima-Zohra Imalhayène, was the first Algerian woman to enter the French Academy. Appointed Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, she claimed to write “with a sense of urgency against regression and misogyny,” illustrating the lives of emancipated heroines.

As for the diva of Arabic song Ouarda Ftouki (1939-2012), nicknamed Warda al-Djazaïria and called “the Algerian rose,” she married a man who forbade her to sing. Known in particular for her patriotic songs, she would sing again after her divorce. She was quoted as saying, “It’s in Paris that I learned to love my country, which is Algeria, and Egypt, and to love music.”

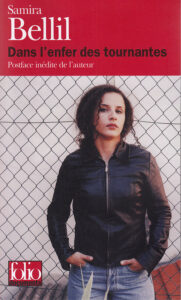

The exhibition puts us in mind of so many women who were confronted with violence, like Samira Bellil (1972-2004), victim of misogynistic criminals, who upset public opinion in 2002 when she denounced gang rapes in her book Dans l’enfer des tournantes (In the Hell of Rotations), a book in which she paid homage to the neuropsychiatrist Boris Cyrulnik, who was marked as a child by the deportation of his parents, immigrants from Ukraine and Poland.

Moudjahida

A famous lawyer, Gisèle Halimi (1927-2020), born in Tunisia, is known for having supported the nationalist militants of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) against the French army. Dreaming of changing the relationship between women and men, she notably defended the moudjahida Djamila Boupacha. Halimi also signed the manifesto of the 343 to obtain the legalization of abortion, and won the Bobigny trial with the release of a young girl charged with having had a clandestine abortion after being raped.

Gisèle Halimi, born Zeiza Taïeb, defended the oppressed. Her specialty? Conducting media trials to move public opinion and obtain major advances in legislation.

In song, Dalida (1933-1987), from Egypt, evoked migration and travel in the song “Salma Ya Salama” and in “Les Gitans,” a ballad about wanderers who have no borders; she celebrated the children of Piraeus and the dance of Zorba. Shortly before she committed suicide, she was in the film The Sixth Day by the Egyptian director Youssef Chahine, adapted from the novel by the French writer of Syrian-Lebanese origin Andrée Chedid.

The exhibition also transports us to Senegal, with the boxer Amadou M’barick Fall (1897-1925), known as Battling Siki and the poet, writer and politician Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001) who developed the concept of negritude of Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), writer and politician from Martinique who was inducted into the Pantheon in 2011.

“Paris, my home”

Among the personalities from the United States, you’ll find the dancers Loïe Fuller (1862-1928), known for her serpentine dance; Isadora Duncan (1877-1927); and Josephine Baker (1906-1975), who became a Resistance fighter in the 1940s, later decorated with the Legion of Honor. Baker was committed to Martin Luther King, Jr’s fight for civil rights, and became the first black woman inducted into the Pantheon in 2021.

There are also the photographers Man Ray (1890-1976) and Berenice Abbott (1998-1991), and the poet and writer Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) who said: “America is my country and Paris my home.”

Immigration, integration, identity issues, quarrels of memory: the exhibition brings out the shocks of history, tragic, glorious or fraternal, and the opening to the world.

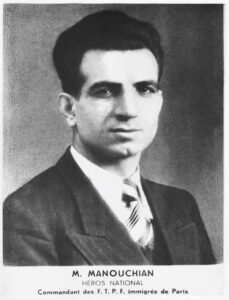

In recent years, there have been calls for the Armenian Resistance fighter Missak Manouchian (1906-1944), a worker and poet who was handed over to the Germans by the French police and shot along with his comrades featured on the Affiche Rouge (Red Poster), to be included in the Pantheon. Sad consolation, as well as this Medal of the French Resistance awarded posthumously in 1947.

Sadness written under the pen of the poet Louis Aragon in 1955, who in his “Strophes pour se souvenir,” pays tribute to “23 strangers and yet our brothers.”

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)