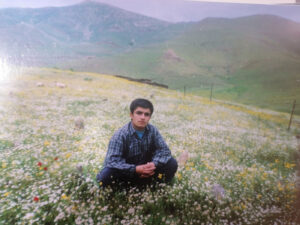

At the tender age of 13, Jassem Ghazbanpour began photographing the daily life of people in the province of Khuzestan, in southwest Iran. By 16, he was recording images in the field for the Iranian forces during the Iran–Iraq war of 1980-88. His home city, the inland port of Khorramshahr, lay only ten miles from the besieged city of Abadan. Ghazbanpour covered the gruesome aftermath of Saddam Hussein’s chemical attack on Halabja, Iraq. He went on to document the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and the war in Afghanistan.

His photographs were published in Time magazine and other international publications; they captured war’s hard living, from fighters on the move to survival in underground bunkers. As a member of Iran’s Arab minority, Ghazbanpour had access other photographers lacked. He remained a freelancer, thereby safeguarding his independence. He belongs to the generation of Iranian war photographers who followed in the footsteps of iconic black and white photographer Kaveh Golestan (1950–2003).

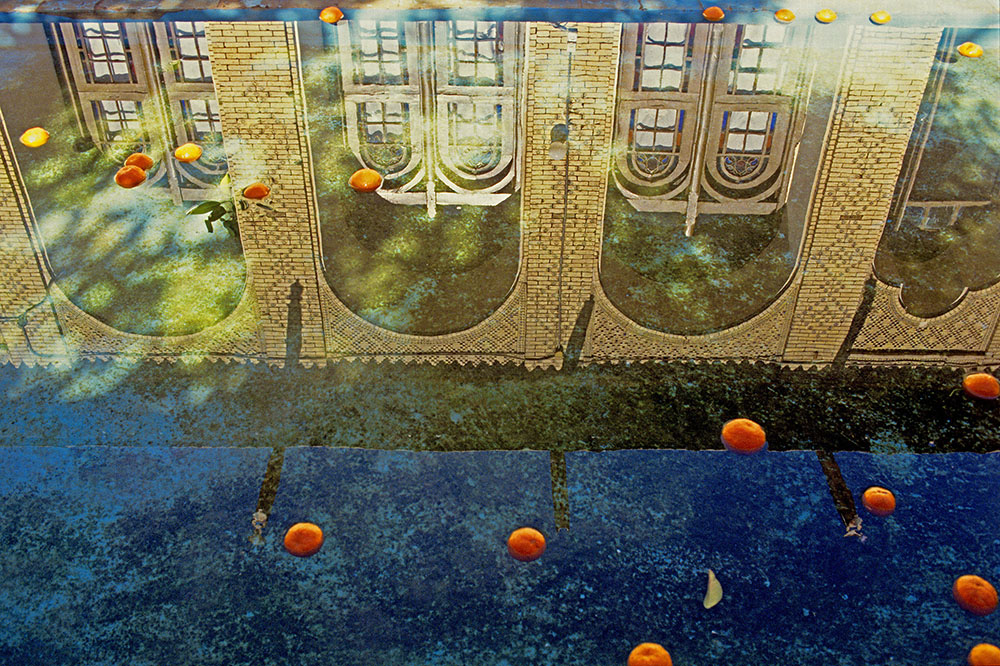

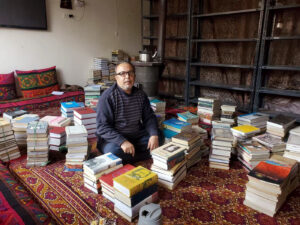

Ghazbanpour never left war reporting, but he began to narrate it in different ways, by following families or by documenting the writing and graffiti on walls, especially in Khorramshahr. He brought that same intimacy and storytelling to the photographs of home life in Iran.

Khorramshahr is about 900 miles from where he now lives with his wife Vida Zarkeshan in Tehran. It takes him between 12 and 18 hours to drive to his mother’s. And that’s not just because of the Iranian capital’s notorious traffic jams.

“It depends on Jassem, if he stops and takes photographs,” explains Zarkeshan, the English speaker in their household, who translates my questions for her husband and his answers for me. “He likes to tell the stories of his life, what’s happened to him. He wants to complete the story with photographs. He likes scenarios with a beginning, ups and downs in the middle, and an end.”

Each of the photographs shown in his Home series for TMR is part of a more extensive collection of images. Considering the experience of war that trained his eye, these photographs — whether they be of himself, his pigeons, another photographer’s house, or a makeshift shrine — take on a greater poignancy. For Ghazbanpour, home is where he points his camera.

—Malu Halasa

Special thanks to Salar Abdoh.