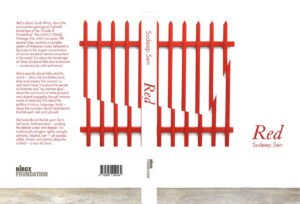

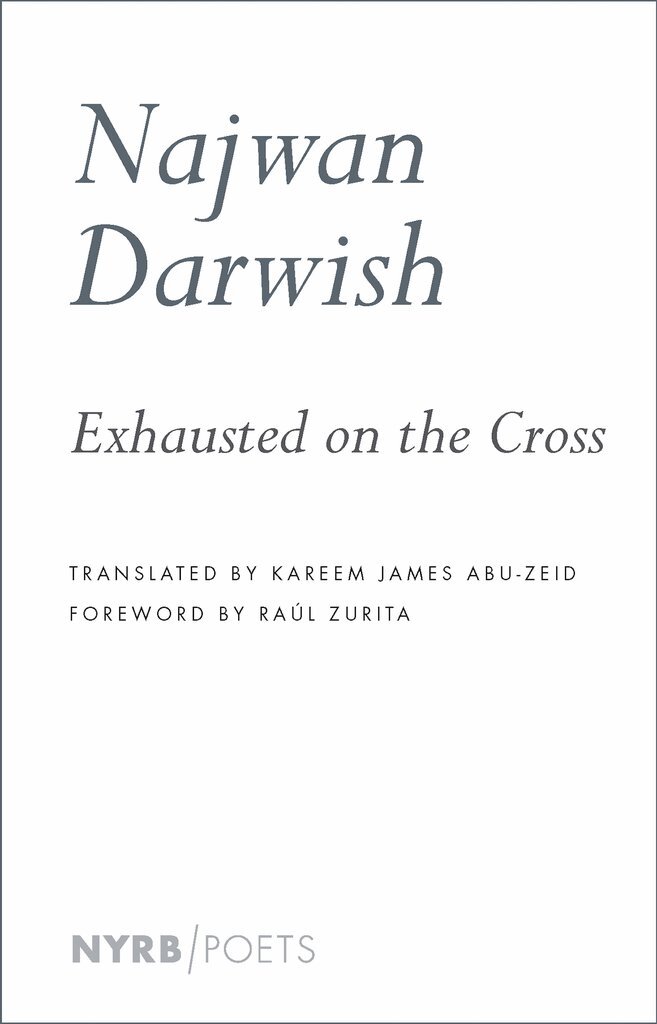

Exhausted on the Cross by Najwan Darwish

Translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid

NYRB Books 2021

ISBN 9781682375526

Patrick James Dunagan

Poetry’s role highlighting human rights abuses under despotic regimes has a lengthy recorded history, dating at least as far back as ancient Greece, evident in such works as Sophocles’ Antigone. Across ensuing centuries, untold numbers of poets have written from under the weight of oppressive circumstances, giving voice to those suffering through life under the harshest of conditions.

The poems of Najwan Darwish continue this lineage. His first published collection of poetry translated to appear in English, Nothing More to Lose (translated by Kareem James Abu-Zeid and also published by NYRB in 2014) received positive acclaim from reviewers in the States, who saw it as marking a fresh turn in Arabic poetry, for its pared down, often raw confrontation of the universal injustice inflicted upon Palestine. This raw sparseness, bereft of much if any flourish in terms of style, traditional or otherwise, along with his lack of abidance to classical Arabic metrics, sustained mostly by way of palpable forthright statement alone sets Darwish (no relation to Mahmoud Darwish) apart from predecessors. There is little of enticement directed towards readers.

Exhausted on the Cross, his second collection, also translated into English by Abu-Zeid, expands upon his previous work while continuing to convey direct testament of the imagination as ravaged by the brutal ongoing realities of daily life faced by the Palestinian people. Living on divided land, with many families split apart for generations now, the state of occupation echoes as if endless. Darwish shows that it no longer manifests as a disruption but instead as a defining sense of normality. He does not employ literary devices or probe his possible inner struggles over whether to embrace a Western, modernized identity. Though he went to school for medicine but abandoned the profession to work as a cultural journalist with Al Araby Al Jadeed (The New Arab) based in London, no autobiographical fragments of his life appear in the poems. His attention remains focused upon the land of his birth and the devastation occurring there.

Exhausted on the Cross is introduced with a bracing and remarkable foreword by Chilean poet Raúl Zurita, who like a wary traveler, signals the rough journey ahead:

The characters that move through the seven sections that make up this book are exhausted, exhausted in an infinity of crosses that rise in an infinity of places. Expelled from their ancestral land, permanently besieged and persecuted, women who have lost everything—their houses, their neighborhoods, their children—make present to others, to me, to you, to the reader, that in this land of victims and perpetrators, displaced and disappeared, all the rest of us are survivors. And if we can affirm that we are facing political poetry, it is because we do it as survivors of an unfinished war. Far removed from any pathos or self-pity and, on the contrary, endowed with a stirring familiarity with everything it names, a familiarity that often resorts to irony and humor, Najwan Darwish’s poetry travels through the villages, landscapes, neighborhoods, cities, and towns of a history that is three millennia old, one that, in each of its corners, preserves the remains of a permanently shattered eternity, as if there were an underlying god, not named, who took pleasure in weaving together suffering and misfortune.

Born in 1978, and having lived through both intifadas, Darwish has come of age as a poet while Palestinians grapple with the continuous inertia of the situation even after decades of unrelenting struggle, political as well as militant, in blunt recognition there is not much hope of any change. As a result, the outlook his poetry offers is, not surprisingly, quite bleak.

“It was all for nothing,

it was all

without merit,

without reward”

(“As for These” 69)

Forced to bear daily witness to devastating events without any offer of just remediation, he regularly evokes in his work the helpless travesty of the circumstances.

“The sea:

hope embroiled with despair,

despair distilled from hope.”

(“The Sea” 68)

Nobody deserves such a life as testified to by these poems, least of all children. Darwish acknowledges the harsh reality greeting those innocently born into the midst of a conflict that remains nothing less than an undeclared war receiving global condemnation. Traditional Palestinian families are routinely set upon by soldiers and settlers, and children as well as adults are manhandled, shot, killed or arrested without charge and held in “administrative detention,” which is completely illegal in democracies that abide by the rule of law, respecting the writ of habeas corpus.

Israel frequently declares itself the only democracy in the Middle East, but what distinguishes a democracy from surrounding autocracies if it continues to practice such horrors? (The same question applies to U.S. drone attacks and other endlessly ongoing military provocations ever on the rise since 9/11.)

Children remain one of Darwish’s central tropes:

“the children born amid the shelling

in these sullen hospitals

are simply companions

joining this family we’ve created

from the ruins of our families.”

(“Family” 84)

The perseverance of Palestinians is remarkable in terms of their character, their strength. Life continues, no matter how many are arrested without charge in the West Bank or killed during the sieges of Gaza. Even in conditions of outright war in the streets. Palestinians as a people have had little choice since 1948 but to resist. Their refusal to cower or fade away reflects an essential nature at the heart of all human character (also demonstrated by the actions of Antigone): Defiance. As Darwish insists, “Fate’s never heard me sigh.” (90) Even as no relief arrives, Palestinians carry on buoyed by way of their unbridled resistance:

“Fate wrecked us,

but still we emerge from the rubble

with satisfaction on our faces.”

(“From the Rubble” 90)

What is wrong is and always will be wrong. The suffering of Palestinians unites their struggle with so many others who have endured across humanity’s vast history. As Darwish puts it:

“People are simply people.

Peel off the languages, and all you’ll find

is women and men.”

(“In Constantinople” 88)

Groupings formed by nationality or religion consistently fail to recognize the greater commonality of existence — an argument driven home in “Visiting Hafez”:

“‘Arabs’ and ‘Persians’—what nonsense is this?

When I look in the mirror, I see only your faces

coming to me from Syria, cleansed by the dawn

and the soil of Maysalun.

They’re plundering the museums

while our sun, still black, floats on Baghdad’s river.

Arabs and Persians, after all of this!” (14-15)

Poetry will not resolve these issues. Perhaps nothing will. Yet Darwish’s poems do at least convey some element of the abysmal grief, shock and sorrow with which millions go about their daily lives in an area of the world heralded for its beauty as well as historical and cultural riches. Sadly, this has now become an old story. One bearing repeated voicing.

Abu-Zeid has undeniably secured a place for Darwish’s poems among non-Arabic readers, his translation providing ready access to an Anglophone audience that is destined to grow in size and who would otherwise have no idea that such poetry in Arabic exists. This is a major accomplishment. However he has also made one slight yet rather regrettable alteration to the ordering of sections in Exhausted on the Cross compared to Darwish’s original 2018 collection Ta‘iba al-mu‘allaqun. Stepping a bit outside his role as translator, he flipped the book’s first two opening sections. As he describes, “the Arabic begins with the section “With the Kaaba on Its Back,” but I felt the poems of “An Ancient Breeze from Wadi Salib” would be better suited to open the book in English, due to their wide-ranging themes and geographies, and Darwish was gracious enough to agree to make this change.” (125)

Although Darwish gave approval and the difference may seem slight, it nevertheless alters how the reader enters into the poems. Of course, this does not detract from the importance and power of Darwish’s work. Nonetheless it feels as if Abu-Zeid made the change to situate Darwish’s book for the non-poetry reader, those more interested in geopolitics i.e. looking for “wide-ranging themes and geographies” surrounding the work, rather than the sustained lyric voice bared of all but sorrow commonly raised across the work as whole.

In effect, reading the opening poems as arranged by Abu-Zeid slightly misleads the reader as to the rest of the book. Darwish’s original opening poem, “Pass It”, is a first-person lyric declaration of sacrificial acceptance of one’s fate (reading in part): “Pass it to me, I said”[…] “Pass me this hazy bit of sky / hung / above a sea that’s been dead since forever”[…] “Pass me this pit in the earth”[…] “pass me my death.”(25) It has none of the exoticism of locale paraded forth in Abu-Zeid’s alternate opening poem, “Mount Carmel”, for example “and some mornings the call to prayer / comes in quietly from the Istiqlal Mosque (borne / on an ancient breeze from Wadi Salib)”. (3) It is not as if the poems do not belong in the book but they clearly do not situate the reader in quite the same experience as the rest.

Darwish’s original ordering also presents the title poem as closing the book’s first section. The final lines offer a benediction of sorts over what is to follow: “Bring me down, / let me have my rest.” (36) Yet of course, there is no rest for the speaker in Darwish’s poems. With the poems of his original opening restored to place, the gambit propelling the rest of them onward is clear. As a poem appearing later in the book states: “I advance in defeat.” (“In Defeat” 59)

Continually forced forward, the poet must also look back with the rest of his people on all that has been lost. What awaits upon tomorrow, remaining the unknown factor, will not stop the determination never to give up the struggle for liberation.

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)