Our guest columnist Sherifa Zuhur is a scholar and musician who plays five-string violin in San Francisco Bay Area’s Aswat Ensemble, which features a section of six to seven ‘ud players. Aswat has performed Arabic, Turkish, Palestinian, Sudanese and Nubian music, including a few compositions by the superlative Egyptian-born ‘udist Hamza al-Din (1929-2006) who emphasized the instrument’s spirituality, and the Nubian musical tradition. The ensemble is preparing a concert of Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan music led by Dr. Salaheddine Bedoui, who plays violin and ‘ud. “We are inspired by ‘ud masters, past and present,” Zuhur declares. —Ed.

Sherifa Zuhur

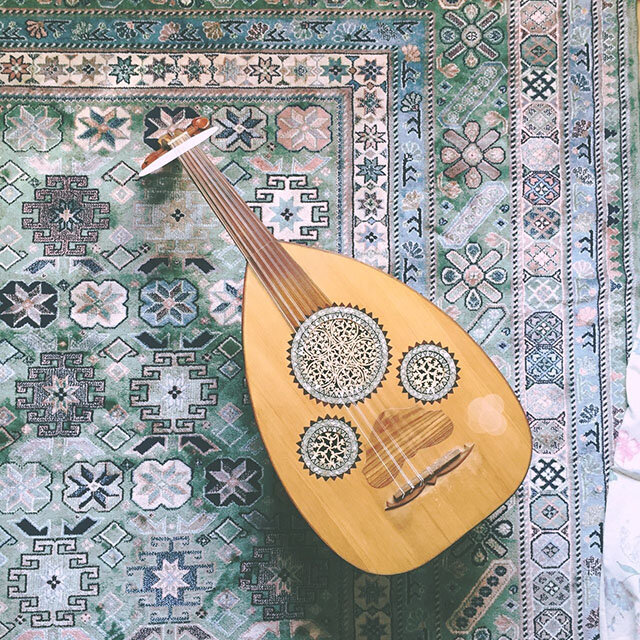

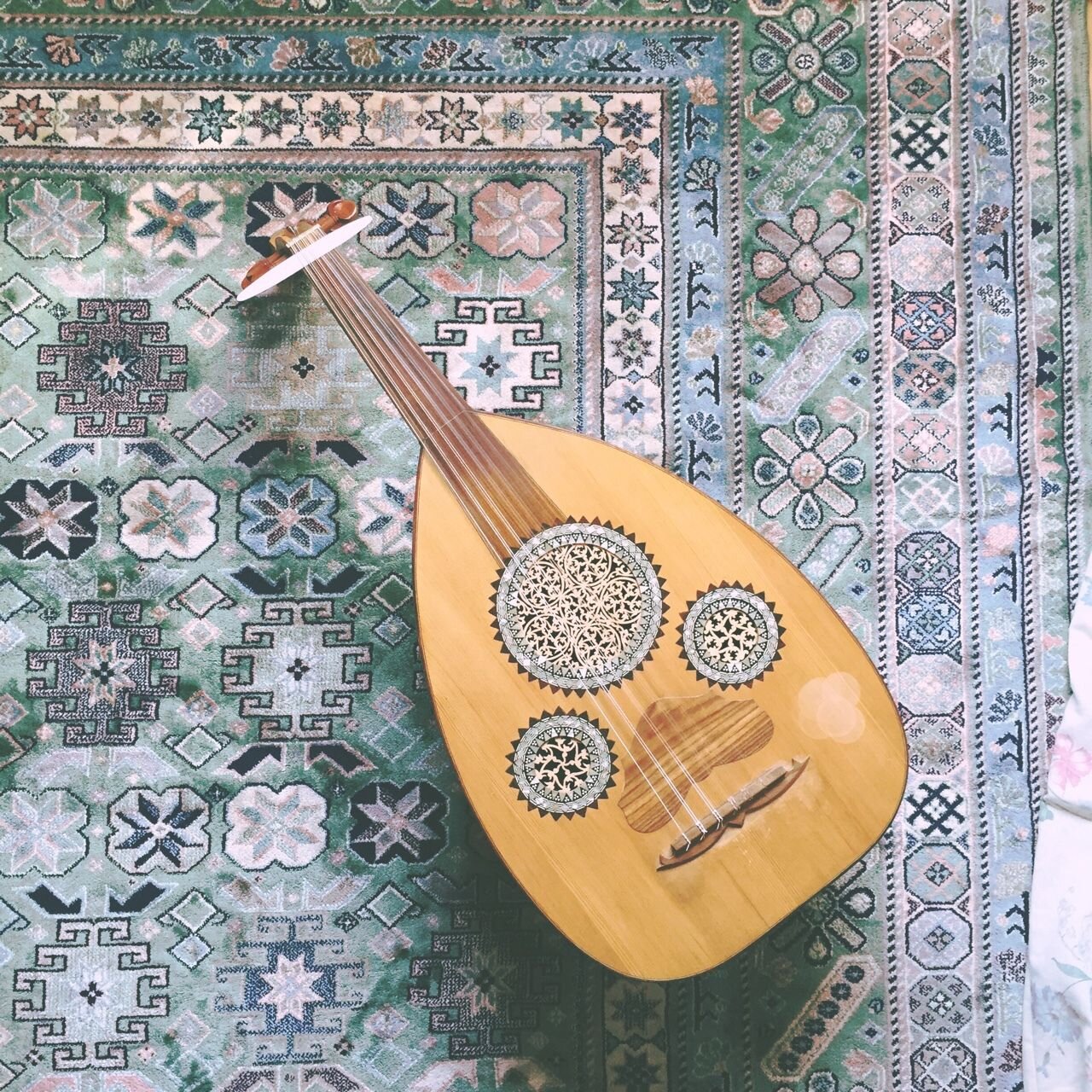

Musicians embrace a deep intimacy with their instruments, and the ‘ud (oud) has a particular warm tonal character that lends itself to a lifelong love affair. In Arabic, a great ‘awwadi (‘udist) makes his instrument resonant, as in the title of a song performed by Lebanese singer Fairuz, “‘Udak ranan,” (Your ‘ud is resonant). The lyrics continue “Strum and keep strumming/Tell me this tune is for you/A true song and more beautiful than words/Play a tune that enters my heart.”

Syrian refugee Bassel Al Qatreeb fled his home town of Salamiyah and now lives in Leipzig, Germany, where he performs on his ‘ud and serves as a cultural ambassador, including as the resident ‘udist with the Leipzig Orchestra, where Arab quarter tones blend with classical music. “The ‘ud is a special language for me when I can’t express myself in German,” says Al Qatreeb. Another Syrian refugee, Mohamad Zatari, is a composer and ‘ud player from Aleppo who now lives in Bucharest, Romania, where he also seeks to bridge eastern and western musical traditions. His performances have included a fusion of Arabic, Persian and Romanian music. Zatari learned the ‘ud from teachers in Syria where, he says, “a mentor teaches you music, philosophy and morals.”

Arab Shaman: Remembering Hani Naser, by John Densmore

The ‘ud, a wooden instrument of beauty, is a short-necked plucked lute whose origins may date to the Bronze Age—one archeomusicologist at the British Museum reports that the museum has found an ‘ud dating from the Uruk Period, roughly 3,500-3,200 BC. The ‘ud is prominently featured in Arabic, Turkish, North African, Armenian and Iranian music to accompany the voice, in ensembles, and as a solo instrument. From the Middle East and North Africa to its immigrant communities abroad, ‘ud players can be found in current popular hits and regional folk styles, and maintain the music’s soul with their improvisational skills.

Many great Arabic singers relied on wonderful ‘ud players, but some of these are perhaps now more famous as composers. This was the case with Muhammad al-Qasabji (1892-1966) and Riyadh al-Sunbati (1906-1981) who accompanied and composed for Umm Kulthum (1900-1975) but were ‘ud masters in their own right.

Farid al-Atrash (1915-1974), of Syrian Druze origin, spent much of his career in Egypt, and was famous as a composer and singing star in films, as well as recording and performing. He was known as the prince of ‘ud for his masterful playing and improvisations (taqasim) which explore the potential of the subtle Arabic tonal modes (maqamat). Among his taqasim was one based on Isaac Albéniz‘ Asturias (known as “Leyenda”). His ‘ud replaced the piano line and fused a flamenco inspiration with Arabic musicality.

Al-Atrash played a wide spectrum of compositions ranging from complex and traditional Arabic-style pieces to others based on folk melodies to more modernist linear pieces for large ensembles. Because he sang and played in both Egyptian and Levantine styles, his legacy was particularly rich, unforgettable songs being “Awwil Hamsah” and “al-Rabi‘ah,” in addition to many compositions for dance.

Aleppo, Syria produced an intricate and beautiful repertoire of vocal music accompanied by takht (small ensemble) or orchestra including the ‘ud. The excellent Syrian ‘ud player Amer Ammouri has performed with the Syrian master singer of the Aleppine qudud, Sabah Fakhri. Ammouri produced several CDs of taqasim.

Egypt remains a center of Arabic music and recording, although the explosion of pop music post-1975 tended to discourage the ‘ud. Shaykh Imam (1918-1995), frequently teaming with poet Ahmad Fu’ad Negm (1929-2013) created a repertoire in which the ‘ud dominates voicing concerns of the poor, working classes and revolutionary causes in Egypt, and also of Palestine. George Michel (1970-1990s) is very well-known to Arabic musicians, for his masterful technique. He became a professor at the Cairo University of Music.

Lebanon’s musicians like Wadi’ al-Safi (1921-2013) played the ‘ud onstage to accompany his singing, and the Rahbani brothers, Assi (1923-1986) and Mansour (1925-2009) included the ‘ud in their compositions incorporating Lebanese folk melodies and instruments. In Lebanon, Arabic music has since simultaneously veered into pop music and maintained its connection to classical Arabic music. Marcel Khalife (b. 1950) who plays the ‘ud, studied at the National Conservatory of Music in Beirut, taught there and elsewhere, and started an ensemble, Mayadeen in his native town Amchit. He toured widely internationally, gaining renown for compositions and arrangements of folkloric and nationalistic lyrics, including for the Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish. He composed for dance ensembles including Caracalla, and for film soundtracks. His publications on Arabic music range from compositions for traditional Arab instruments to an ‘ud methodology, and music theory.

Charbel Rouhana (b. 1965) is perceived as one of the finest ‘ud players in Lebanon for his delicacy and sensitivity. He joined Marcel Khalife’s first band Mayadeen and created an ‘ud method used at the national conservatory. Among his notable duets was one with Khalife in the 1995 album Jadal. Another was on Doux Zen with Elie Khoury, which has a classical feeling followed by discord in a fugue-like final [q]aflat (ending cadenza).

Other compositions have an experimental feeling. Rouhana was part of musical projects like his 2007 Beirut Oriental Ensemble and Tarab Safar, which includes a great deal of fusion. His composition “al-Quds” was presented in fall of 2020 and with his brother, Boutros Rouhana, a song for Beirut, to memorialize the city following the August 2020 explosion there.

The Assyrian-Iraqi Munir Bashir (1930-1997) taught in Baghdad, then performed in Beirut, and then settled in Budapest, Hungary where he completed a doctorate in musicology at the Franz Liszt Conservatory under Zoltan Kodaly. After 1973, he founded the Iraqi Traditional Music Group and led the Babylon International Festival of dance, music and theater for some years, though he mainly performed in Europe. His brother Jamil Bashir was an excellent ‘ud player and vocalist, and his son Omar was presented as an heir to his style.

Naseer Shamma, born 1963 in al-Kut, Iraq, is a renowned ‘ud master, and UNESCO Artist for Peace. He relocated to Cairo, Egypt, performing numerous concert projects involving music “readings” and improvisations inspired by modern poetry. Among these is “From the Heart”.

Shamma created many soundtracks for Iraqi and Arab plays, a ballet, Shahrazad, film soundtracks and collaborations with visual artists. He founded various orchestras including the Orchestra al-Sharq with 70 musicians and then the Arabic Oud House in Tunis in 1993 and in Egypt in 1998.

Shamma subsequently created branches of the Arabic Oud House in Abu Dhabi, in Constantine, Algeria and at the library in Alexandria, Egypt.

Shamma’s first female student was Sherine Touhamy, who taught at the Oud House in Cairo after graduating, and since 2009 at Bait al-Oud in Abu Dhabi. She also heads a female band, Najmaat. Here she plays a masterful version of Farid al-Atrash’s “Touta”.

Hazem Shaheen, of Alexandria Egypt, also a graduate of House of the Oud was awarded Best Oud Player in the Arab world, in Beirut in 2002. He is a founding member of the Eskendarella ensemble in Egypt which has popularized some revolutionary songs of Sayyid Darwish and Imam Shaykh, mentioned above.

Another preserver of the ‘ud style of Iraq is Yair Dalal (b. 1955) whose family emigrated from Baghdad to Israel where he performs, teaches and works to preserve Iraqi and Iraqi-Jewish music. He has produced 14 albums.

Sakher Hattar (b. 1963) is a well-known ‘ud master in Jordan, where he plays solo and with al-Nagham al-Arabi ensemble, and heads the Arabic music department at the National Conservatory of music. He has also served as faculty for the ‘ud at Simon Shaheen’s retreat, as did the late Bassam Saba (1958-2020) of Lebanon. Bassam played four instruments including the ‘ud, and his multi-instrumentality infused his playing. He co-founded the New York Arabic Orchestra and returned to Lebanon to direct the National Conservatory of Music.

Naser Musa is a Jordanian of Palestinian descent who moved to the U.S. in 1982, and is considered an excellent ‘ud player. He has played with the Qadim Ensemble and toured with the Persian band, Niyaz along with singer Azam Ali and with the Senegalese singer Youssou N’Dour.

Omar Abbad is a Jordanian ‘ud player, who spent time in the United States and returned to Amman where he performs and teaches at the Jordan Academy of Music. He is also known for his ‘ud teaching method.

Nina Boukatchian, born in Lebanon, and raised in Sweden, studied at the Arab Music Institute in Cairo and is based in the UAE. Her recordings can be found under the name, Nina Oud. Here she plays and sings “Lamouni ya gharou minni”.

The ‘ud is essential to Turkish classical music, and to the Ottoman musical tradition in Arab countries, where in the 19th and early 20th centuries it was mostly played by women. It was estimated that 70% of young women played the ‘ud in Istanbul early in the twentieth century as a prerequisite to marriage (as was true elsewhere in the Levant). Among them were Hamiyet Yushteges (1915-1996), who was also a singer and actress, and Mary Goshtigian.

Cinuçen Tanrikorur (1938-2000) an ‘ud master, became the director of Turkish classical music at Ankara Radio and is considered the greatest composer of the Turkish classical tradition, with over 500 instrumental and vocal compositions. Yurdal Tockan, ‘udist and composer who plays with Göksel Baktagir and others, is a sensitive performer with a great dynamic range as in Nihavend Saz Sama’i.

The ‘ud is central to the musical tradition of the Arabian peninsula. Muhammad ‘Abdu (b. 1949) began his career in the 1960s, singing in a traditional style and is considered a great master of the ‘ud. He is a superstar in Saudi Arabia, but the Kingdom did not permit live concerts for many years until 2017. He sometimes performs with a huge orchestra, showcasing his voice, rather than the ‘ud; but otherwise played the ‘ud while singing, in the traditional Arabian majlis setting.

Faysal Alawi of Lahj, Yemen illustrates the use of voice and ‘ud in musiqa sha’bi, or folk music which differs from area to area.

Abadi al-Johar is a virtuoistic ‘udist, singer and composer, beloved by audiences in Saudi Arabia. He was given the title of Ikhtabout al-‘ud (Octopus of the Oud) by the late, great singer, Talal Maddah. He wields some of the Spanish inspiration in improvisation as presented by Farid al-Atrash in this performance.

Tuha (Fathiya Hassan Ahmad Yahya) was born in 1934 in Hasa and moved to Mecca at age five. She began playing the ‘ud and singing as a girl, encouraged by her father and brother, who played. She became famous in Jidda, as a singer and ‘udist in weddings, in which the festivities are segregated. She composed hundreds of songs, 300 of which have not been recorded, and collaborated with the great singer Talal Maddah.

Le Trio Joubran are from Nazareth, Palestinians from inside the Green Line, and are unique as an ‘ud trio, first performing together in 2003. They are Samir (b. 1973), Wissam (b. 1983) also a luthier like his father, and ‘Adnan (b. 1985). The two elder brothers were a duo prior to teaming up with their younger brother. Their performance style is fiery, electrifying, and experimental. Here they performed live at the Olympia in 2016.

Their recent recording, The Long March produced by Renaud Letang is more cerebral but also modernist. Like other ‘ud masters featured here, they have plunged into dialogue in the world music scene, most recently in the single “Ascent” with Iranian vocalist Alireza Qorbani.

Kamilya Jubran, born in Akka, studied Arabic music at the Jerusalem conservatory. She sang with the East Jerusalem-based musical group Sabreen, playing the qanun from 1982-2002. She has performed as an ‘udist and vocalist since the early 2000s, in concert and recording six albums, most recently with Werner Hasler in the band Wa. Her very distinctive vocal style can dominate as in Bahabb al-bahr and her latest album veers into the experimental and rap/techno.

In the United States, there were many ‘ud masters prior to the dying down of live venues. Most relied on nightclub or restaurant performances, weddings or parties, often doubling as a vocalist and working outside of music to make ends meet. Of the ‘udists of the previous generation in California were George Khayat, Maroun Saba, Maurice Saba, Adel Sirhan, Najib Khoury, Suhail Nasser, ‘Ali Vassal, Hani Naser, Fadil Shahin, the two George Eliases and Abdullah Qdouh. Fadil manages a restaurant/club and his nephews carry on the musical tradition in their own nightclub.

The Armenian American communities produced many fine ‘udists. Aspects of both Turkish and Arabic styles are preserved through these, as well as Armenian heritage: John Belizikjian (1948-2015) who played in symphonic venues, and nightclubs, in “Armenian Medley”; Haig Manoukian (1941-2014) in California; Richard Hagopian (b. 1937); George Mgrdichian (1935- 2006) who also began in nightclubs; and John Berberian (b. 1941) who began his career in Massachusetts. Carrying on that same tradition is Boston-born Brian Ansbigian. Ara Dinkjian similarly began his career as an ‘ud player accompanying his father, a folk singer.

In 1979, the Lebanese scholar ‘Ali Jihad Racy (b. 1943) established a Near Eastern ethnomusicology ensemble at the University of California, Los Angeles which provided a more formal approach to classical Arabic music and training many from outside the Middle East. Racy’s students established similar ensembles elsewhere in the U.S. (I started one sponsored by Harvard University and MIT in Boston). These ensembles were supplemented by excellent community musicians and benefited from the interest in world music in their audiences.

Palestinian-American Simon Shaheen (b. 1955) studied the ‘ud with his father, Hikmat, a teacher, composer and conductor, and then violin from an early age. He also went to the Academy of Music in Jerusalem, the Manhattan School of Music and Columbia University. Shaheen is at the forefront of his generation on both instruments. He started out performing in the nightclub/restaurant scene in New York and successfully transitioned to presenting traditional Arabic music in concert settings, first with the New York based Near East Ensemble; and in performances involving fusion and improvisation with other master-musicians. Here he plays Alcantara.

Since 1997, Shaheen has led a summer Arabic music retreat at Mt. Holoyoke College in Massachusetts, with a roster of excellent instructors including the previously-mentioned A.J. Racy, Sakher Hattar and the late Bassam Saba. They have nurtured the growth of a new generation of performers. The camp often sponsored some very young musicians from the MENA to attend. Simon’s brothers Najib and William are excellent ‘ud players; Najib sometimes reminiscent of al-Sunbati with a preference for the lower notes, and he is a luthier.

Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan music all employ the ‘ud in a vital role, and in many genres, some less well-known to the West and the Arab East. A highly regarded ‘udist is Moroccan, Nasser Houari (b. 1975) who studied at the Conservatoire National de Musique et de Danse de Rabat. He plays in various styles, in a taqsim in maqam Rast (left) or here in a more lyrical and Moroccan style. Non-traditionalists might prefer Dhafer Youssef of Tunisia (b. 1967) whose output is better described as jazz ‘ud.

A must-mention is the late Egyptian-born ‘udist Hamza al-Din (1929–2006) who emphasized the instrument’s spirituality. Hamza al-Din’s mission was to preserve and explore traditional (pentatonic) Nubian music which is played in both the Sudan and Egypt. He also experimented with fusion, collaborating with such artists as the Grateful Dead and Kronos Quartet.

The ‘ud has also played a role in Persian classical and ethnic folkloric music traditions. These forms are distinct from Arabic music and complement a differing singing style. In addition to the ‘ud, the barbat, probably originating in Central Asia, has been revived. With a smaller body than the ‘ud, it has a longer neck and a more airy sound. A long list of great barbat or ‘ud players extends from Abdolvahab Shahidi born in 1914 (or 1922) up to Mansour Nariman (1933-2015) improvising here in Mahour; Hossein Behrouzinia (b. 1962) Mohamed Firouzi (b. 1958) Negar Bouban (b. 1973) and many others.

Female performers, under the rules of the Islamic Republic may not sing, but there are several excellent women ‘udists, among them Negar Bouban (b. 1973), Yasamin Shahhosseini (b. 1992) and Fatemeh Dehghani (b. 1996). Bouban has played with many ensembles, and frequently performed as a soloist. She has produced five albums, and also teaches at the conservatory and has published an ‘ud method. Yasamin Shahhosseini is a highly regarded younger ‘udist who released Gazar and can be heard here.

Traditional Greek music has also included the ‘ud (the outi) as played by singer/composer Grigoris Asikis (1890 – 1966) and Agapio Toumbolis (Hagop Stambulyan, 1891-1965) who played in a Smyrna-style trio with Roza Eskanazi and others.

Despite the popularity and ease of the keyboard, nothing will replace the ‘ud for its aficianados. Fairuz’ song “‘Udak Ranan,” concludes: “Strum and strum hard until you wake up everyone. Night is not for sleeping here, it’s for staying up late. You play so well, play for us!”