Ammiel Alcalay

I. Brief Biography of a Poet

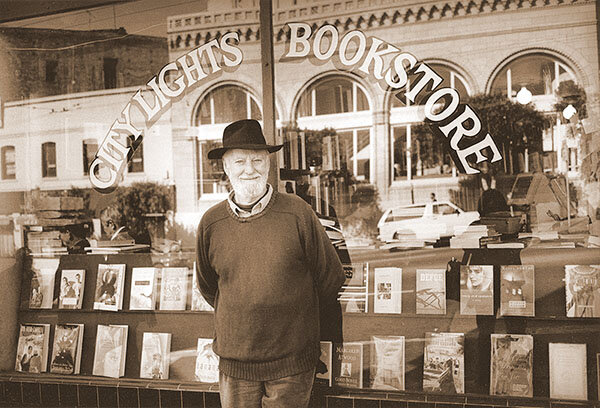

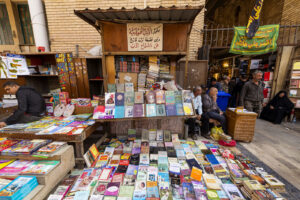

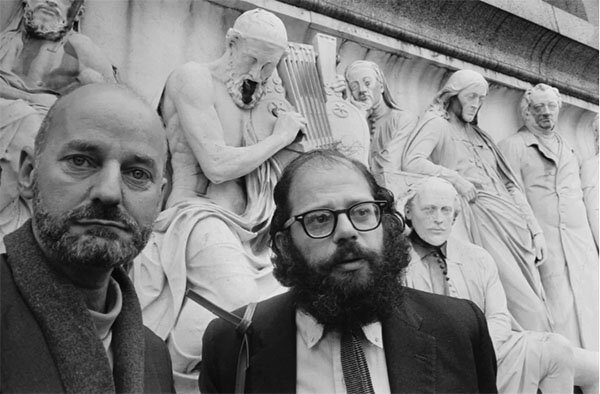

Newspapers all over the world have already published detailed and generous notices in appreciation of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a truly unique cultural figure whose life and work will continue to resonate for a long time to come. Many of the bare facts of his life are well-known: his very transitory childhood, with the death of his father, an Italian immigrant from Brescia, prior to his birth, and the institutionalization of his mother, Clemence Albertine Mendes-Monsanto, not long after the death of her husband. Moving between New York and France, between orphanages and the care of relatives, Lawrence eventually ended up in a wealthy home where his aunt Emily Monsanto had gone to work as a governess. When his aunt disappeared, Lawrence remained with his new family and his more formal education began, taking him to an exclusive boarding school in Massachusetts and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, before enlisting in the US Navy in 1941. He would go on to command a patrol boat during the invasion of D-Day and find himself in Nagasaki peering at the unearthly destruction caused by the atom bomb. With money from the GI Bill, he went on to complete a master’s degree at Columbia University before going to Paris where he finished a doctorate at the Sorbonne in 1949. After moving to San Francisco, he fortuitously met Peter Martin, then a professor of Sociology at San Francisco State and the son of Italian anarchist Carlo Tresca, and they found themselves opening the first paperback bookshop in the US, calling it City Lights, after the Charlie Chaplin film. Soon came the famous Six Gallery reading, the publication of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, followed by the obscenity trial, and the public emergence of the Beat Generation. The rest is history.

II. City Lights

My own relationship to City Lights started, like so many others, with my first exposure, as a teenager, to some of the Pocket Poets: I remember, in particular, Ferlinghetti’s own Pictures from the Gone World, Kenneth Patchen’s Poems of Humor and Protest, Gregory Corso’s Gasoline and, of course, Howl itself. Though I had spent time in the bookshop during a half year or so of living in San Francisco circa 1974, I was working in an auto body shop and not, in any sense, a “recognized” writer. Besides reading City Lights books, there would be a very long detour before I personally reconnected to the shop, the press, and, eventually Ferlinghetti himself, as well as co-owner and publisher Nancy Peters and the rest of the quite small staff running the show. Hearing of his death on February 22nd has put it all in perspective and it feels like a story worth telling.

III. Iraq

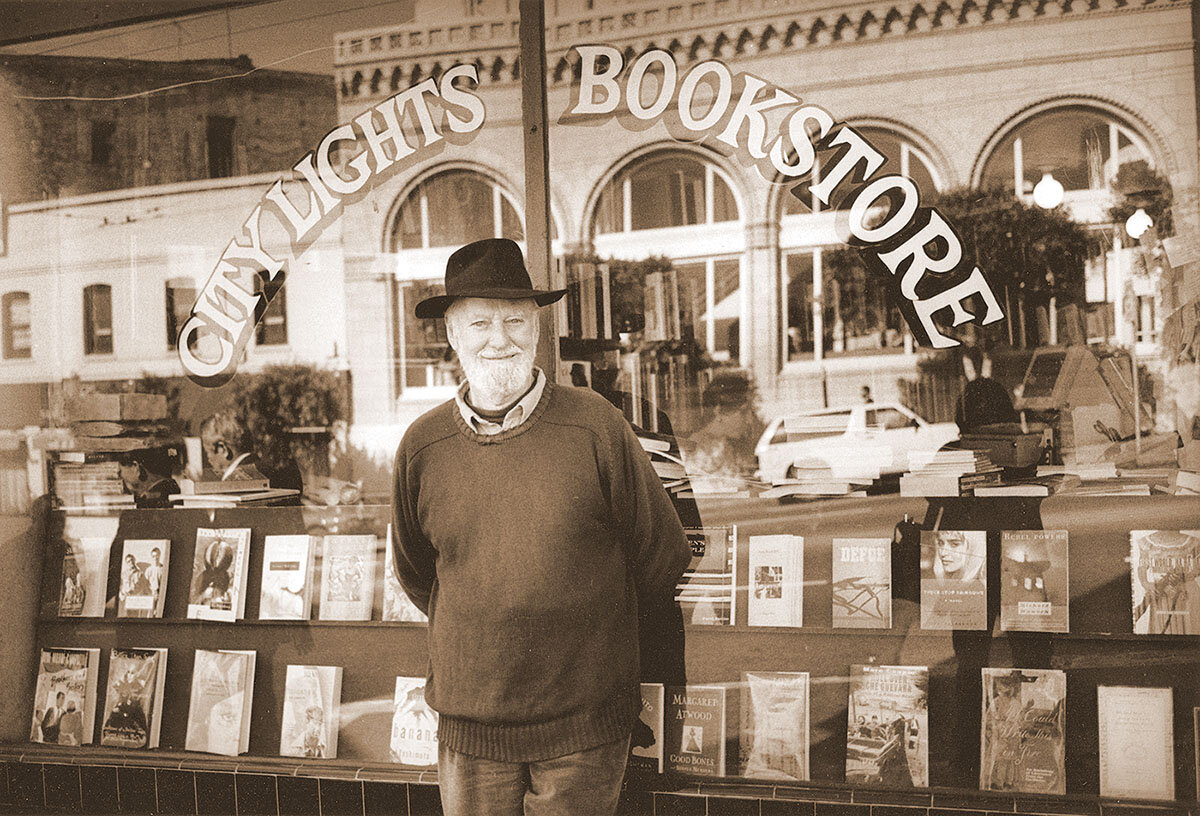

I have spent more than a little time pondering the shameful (and shameless) rehabilitation of George W. Bush over the course of the 2020 election process and the installment of the new American administration. Iraq, and the continuing US role in its destruction, remains the massive and unalterable abyss cutting off all rational political discourse, all ability to connect any dots over the course of events these past thirty years, since the first invasion of Iraq in 1990. And yet, when I heard about Lawrence’s passing at the age of 101, it was one of the first things I thought of because I remember with great clarity and fondness the welcome I got from Lawrence, Nancy Peters, Bob Sharrard, and everyone at City Lights in the build-up to the Gulf War. I had returned to the US from six years in Jerusalem and environs and was having a hard time finding my literary/political footing in New York. As I tried publishing texts that dove directly into the turmoil of the region I had returned from and the intense political involvement of those years, I was met with hostility, incredulity, or both! At City Lights, they were in the process of mobilizing writers and artists against the invasion, an activity I was more than happy to be recruited for. With this initial welcome, I soon came to understand that City Lights could be a home for the kind of work I was doing, and I felt an enormous sense of relief and gratitude as it empowered me to not only publish many hybrid works of my own but help bring other books to the press, including one of the first contemporary Iraqi novels published in the US, Sinan Antoon’s brilliant I’jaam: An Iraqi Rhapsody.

IV. A Visionary Publisher

Though we only briefly alluded to a common Sephardic heritage, I’ve often wondered whether that part of Lawrence may have predisposed him towards my work. He was certainly aware of it, though given the complexity of his upbringing it was hard to tell what it actually might have meant to him. Regardless, when it came time to think about a publisher for Keys to the Garden, an anthology I edited and co-translated that broke new ground— peopled as it was by contemporary Iraqi, Yemenite, North African, Turkish, Iranian and Indian writers who just happened to be Jewish Israelis—it was to City Lights that my immediate thoughts went. My logic—and I feel it has been borne out—was that the limbs joining mainstream Israeli writers with mainstream US publishers, needed to be severed, with extreme prejudice. The idea being that such books—by and for the mainstream—had no possibility of effecting writing at its production point, among other writers, among emerging writers. But by publishing with City Lights, perhaps, finally, such writing might be seen for itself, and not just as a surrogate for nationalist propaganda and part of the US’s favorite nation status in the form of Israel. In fact, because Keys to the Garden was the first collection of its kind in any language, it has gone on to have disproportionate influence on the Israeli cultural scene as well as throughout the region, making many great and unknown writers with roots in the Arab world finally available to Arab readers. It was followed up with a co-translation (by myself and Oz Shelach), of Outcast, a novel by Baghdad born Shimon Ballas, which remains the only book of this major novelist in English. Over the years I would go on to publish a number of other books with City Lights, titles of my own as well as shepherding in work by Juan Goytisolo, Abdellatif Laabi, and many others. These would be added to books by Tahar Ben Jelloun, Etel Adnan, Nawal el-Saadawi, Mohammed Mrabet, Paul Bowles, et alia, creating a very useful and idiosyncratic affinity group of books from and about the region. In addition, during the wars of ex-Yugoslavia, I ended up being the only translator consistently working with material from Bosnia. While many timely and important texts that I translated for mainstream publishers have gone out of print, Semezdin Mehmedinović’s classic work from the siege, Sarajevo Blues, like all the other titles I worked on for City Lights, remains in print.

V. San Francisco

Whenever I had the chance to visit or spend a longer period of time in San Francisco, City Lights always felt like home base. Throughout the course of all these different and varied projects, Lawrence was always attentive, curious, informed, and supportive, even as he and Nancy were less present and Elaine Katzenberger, now Executive Director, took on more and more. As our unique archival publishing project, Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, a student edited series that publishes extra-poetic materials by major and lesser known 20th c. figures got underway, and we began doing collaborative books, City Lights became one of our first partners, and they continue to be. One day I remember going into the office upstairs and catching Lawrence alone at his desk with a pile of Lost & Founds, intently reading. We spoke for a while and he told me how much he enjoyed it when a new batch came in. Needless to say, it was an incredibly meaningful and satisfying moment, one of many that I will treasure as I think of Lawrence today and his continuing journey.

February 23, 2021

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more