America’s Race Problem is Its Caste System

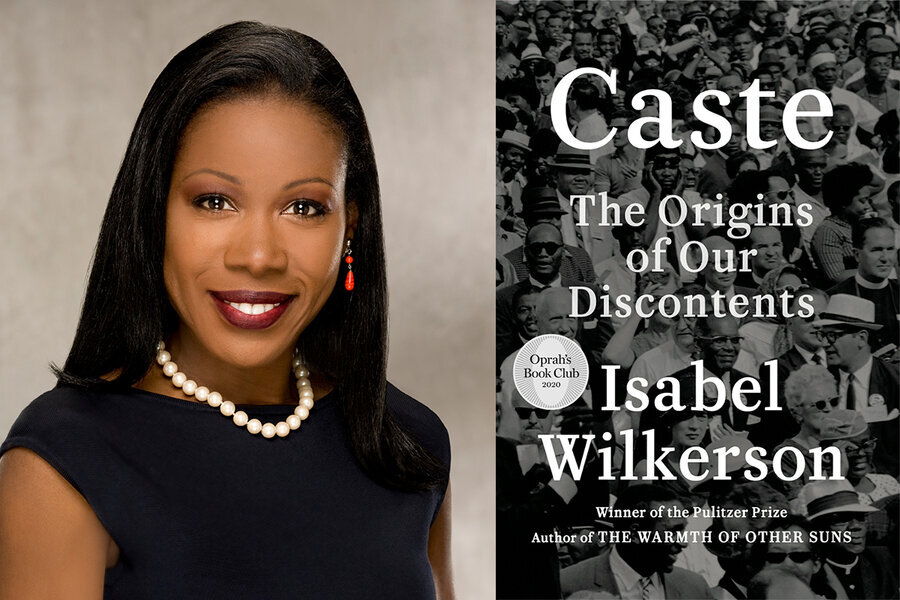

I’m reading Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson. It’s both profound and sublimely easy to read, and strikes me as the most important book I have read recently and perhaps ever. In it, Wilkerson looks at race in the United States—noting that race is an arbitrary and artificial construct—and argues that caste, not race, is the real issue at hand and the structure that the status quo works so hard to preserve. “Caste is the bones. Race is the skin,” Wilkerson states. “Race is what we see, the physical traits that have been given arbitrary meaning and becomes shorthand for who a person is. Caste is the powerful infrastructure that holds each group in its place.” Wilkerson compares the caste system in the US to India and Nazi Germany, which used American racial purity laws as the basis for their own biases.

Those who have already thought and read about these issues will perhaps not find so much new in terms of the information Wilkerson presents, but will likely have many ‘aha’ moments in terms of the connections she draws and the conclusions she makes. Reading the book feels a bit like watching an image emerge in a bath of photographic developer solution; it limns and clarifies what one already knew, and suddenly both recent and past US history make a bit more sense. When we dispatch of the idea of black and white, we see that everyone in the US, particularly more recent immigrants, is placed into the hierarchy of caste, and the notion of social mobility takes on a decidedly different hue. —Monique El-Faizy

The End of Racism

I’ve just read two new novels that call into question how I think about narrative fiction vs. autobiography and memoir, and how I negotiate my own identity—they are Homeland Elegies by Ayad Akhtar (2013 Pulitzer for the play Disgraced), and Track Changes by Sayed Kashua (creator of the hit Israeli TV series “Arab Labor” and author of the novels Dancing Arabs and Second Skin). In both of these very personal stories, the first-person narrator is an atheist or agnostic Muslim who navigates between racist America and not (or no longer) fitting in back in their homeland (Pakistan and Palestine/Israel respectively). While reading these novels I felt incensed by the anti-Muslim suspicion shouldered by the narrators and engineered by Americans and Israelis. It very much put me in mind of the Black Lives Matter movement and how so many of us have been out on the streets, worldwide, trying to change our racist and white supremacist reality. And here I had been thinking that, hell, I read James Baldwin and Franz Fanon in my youth, since then the world has progressed enormously. After all, the USA has had a Black president, and nearly half the population of my native country is now non-white. But progress is always one step forward, two steps backward. Humankind evolves very slowly, over decades and millennia, and the slow pace of change is painstaking. After finishing Homeland Elegies and Track Changes, I asked myself, how can we speed up intellectual evolution? When will we relegate racism to the trash bin of laughable theories, like the flat earth or homosexuality as a lifestyle choice? —Jordan Elgrably

The War Correspondent and the Poets

I just handed in my latest book about Christians in the Middle East, called The Vanishing, to my publishers (it will be published next Spring). The last book I read relating to that research was a French document given to me in Gaza about the Christian settlement there going back to the 4th century, written by a priest at the small embattled church there. My next book will be about moral injury and the concept of evil—in relation to war crimes—so I am reading Dr. Bassel van der Kork’s excellent The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Body and the Healing of Trauma. On my list is to re-read Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil as well as Gitta Sereny’s Into that Darkness and The Healing Wound. Dr. Jonathan Shea’s Achilles in Vietnam is an important reference for me.

For pure pleasure, I am watching “Le Bureau des Légendes” (Le Bureau), which is about the undercover unit of the French intelligence service, the DGSE devoted to field workers who work for years, and it takes my mind off work. I was selected to be a judge for the LA Times Book Prize, and I was sent dozens of non-fiction books to read; the one I am enjoying the most is called The Equivalents by Maggie Doherty, a story of female friendship in the 1960s centered around the poets and writers who attended the Bunting Institute at Radcliffe College. This included great poets like the late Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath, Maxine Kumin, Tillie Olsen, and their interaction with greats like Robert Lowell. It’s a wonderful window into what life was like for women struggling to combine work, motherhood, and other responsibilities while trying to write.

I always read poetry—by Wallace Stevens, Robert Lowell, Hart Crane and Walt Whitman. It soothes and inspires me. —Janine Di Giovanni