Continuously displaced Gazans redefine the meaning of home In Osama Kahlout’s photographs from the war.

A couple of weeks ago I had a call with my mother who resides in the occupied West Bank. She said that she almost witnessed the killing of one of our neighbors living in a building behind my parents’ apartment in Ramallah. A young Palestinian man was shot dead by the Israeli occupation army while walking home. She also said that another neighbor who had been arrested recently is expected to have their home demolished by the Israeli army soon.

She added, “Each night we go to bed expecting to wake up a short while later due to night raids and possibly to the sound of explosions used by the army to destroy houses.”

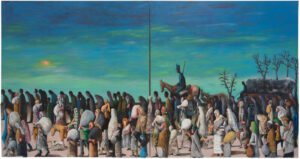

This tool of collective punishment has been used for so many years, dating back to the British Mandate period in Palestine. The house or the home may be one of the central pillars in Palestinian life connected to family and one’s place of birth and origin. Since the Nakba, and 76 years of continuous Israeli colonization, the tent has emerged not as a metaphorical object but as an alternative home forced on Palestinians, who were displaced from their towns and villages as a result of the creation of the Israeli state. Despite the passing of many decades, the Nakba remains a continuous event, as increasing Israeli assaults take place against Palestinians inside and outside Palestine, but especially in the Gaza Strip.

The events I mentioned earlier happened in my hometown of Ramallah, considered the “quietest” area of the West Bank, in what became Area A after the 1993 Oslo Accords. Despite the brutality of such events, they do not compare to the scale of Israeli destruction of homes, dreams, and memories in Gaza since October 8, 2023. Over seven months of genocide have passed during which civilians tried every way possible to protect themselves from the atrocities of the war. Browsing through the Instagram page of Gazan photojournalist Osama Kahlout, the density of newly created camps to accommodate displaced Gazans can be seen, but also the creative structures they have made to shelter themselves or carry out daily activities that people in other countries take for granted. Kahlout not only documents tent structures; he also documents the stories of displaced families and those who are in urgent need of medical aid or evacuation for proper treatment. He calls on people following his pages to help support these families.

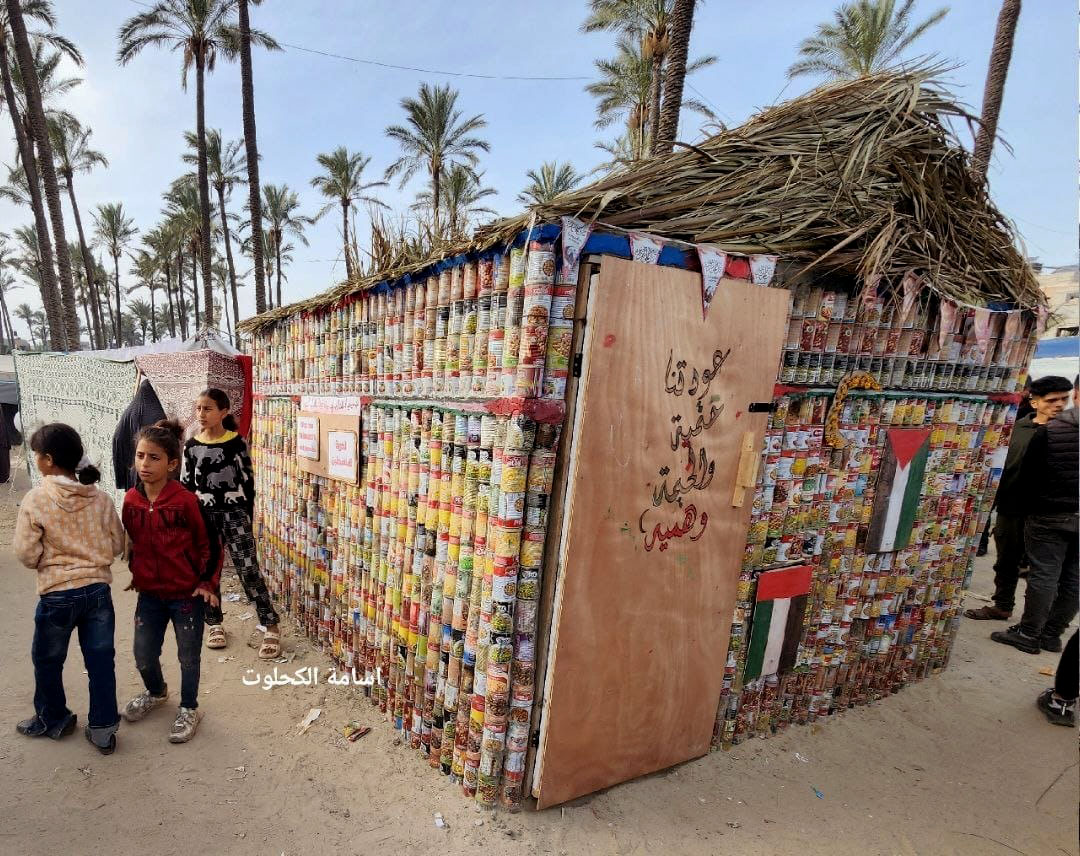

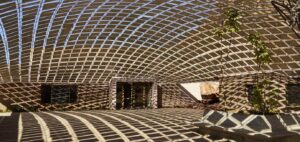

Despite these attempts to carry on with daily life, Gazans in southern and central Gaza Strip have tried to return to their homes in Gaza City and other areas in the north, where they hoped to salvage a life for themselves and their families in their homes or in the remains of their houses. In Deir al Balah, in the central Strip, thousands of refugees had set up tents near the sea. After the Israeli military offensive of Rafah in May, thousands more were forcibly displaced again to areas like Deir al Balah and Nussairat. One of the structures people created was made of food tin cans, which not only reflected on Gazans’ refugee experiences, but also the poor food quality they are receiving with growing difficulty. In an interview conducted by Kahlout, Palestinian woman Dalia Al Afifi told the story of the “tin can” tent. She explained that she and a group of other refugees, including architects, resolved to challenge their current reality of displacement.

“We decided to break the status of pain and sadness five months after the start of the war. Thinking outside the box, we used tins, which are the main source of aid arriving at the Gaza Strip. Hence, we decided to recycle the tins.”

Al Afifi added that she came up with this idea, as the prices of tents had been constantly increasing, reaching 1800 NIS — equivalent of $482 USD. She said that these tents are not only to send a message about Gaza’s reality to the entire world, but they are also used to accommodate newly arriving refugees for a few days until they find a tent of their own. Al Afifi went on to say that according to architect Abdallah Thabet, who helped her design the tent, around 13,000 tin cans were used for this structure. The tent was constructed with the help of a team of refugees displaced from different areas across the Gaza Strip.

The question remains today, how many more tents and tin cans would Deir al Balah need to accommodate the thousands arriving from Rafah for safety?

Taking a closer look at tents in Gaza, one can see different initiatives started by refugees and captured by Kahlout’s lens. One is Khaymat Iqra’, the “reading tent” in Arabic, initiated by the Rowad Al Amal Center for Education and Training. The center serves the middle area of the Gaza Strip and had recently started their initiative creating educational tents, starting with Khaymat Iqra’.

Another similar tent called Khaymat Al-Amal, “the Hope Tent,” was also created in the shelter areas by the beach area in Deir al Balah. These projects are seen by many Gazans as temporary education points that serve children and allow some space for debriefing and unofficial schooling. The founder of the Hope Tent, Aqil Qreaiqea said that the tent started after seven months of the war to reclaim childhood in Gaza and bring education back into children’s lives. Qreaiqea went around the camp to see if people were ready to take part in the initiative. Luckily many welcomed it and several refugees joined forces to offer their expertise in education, teaching, and psychology. This alternative school came together in Al Awda-return-refugee camp uniting collective efforts in the camp with support of donors outside Palestine. Qreaiqea, a former accountant at al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City, had no experience in education but he organized efforts and experiences in the camp and reached out for support to offer this space for children. The Hope Tent serves 200 refugee students from different age groups and runs day and evening shifts with even more demand as Gazans arrive from Rafah.

Qreaiqea explained that students of the Hope Tent had organized an event commemorating Nakba Day and had prepared a full program on their own to remember the atrocities of the past while experiencing the horrors of the present. Although seen as positive alternatives for Gazan children deprived of schooling for over seven months, the priority for many Gazans remains safely going to their homes and securing a dignified life for their families.

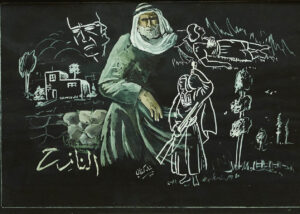

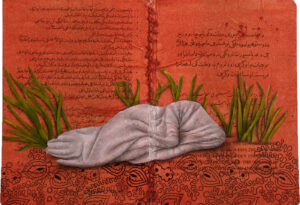

Another form of creativity has been documented in Kahlout’s photographs and stories. In this case, homes in Gaza do not only signify family and safety, but places in which Gazans create art. Kahlout features young artist Muna Hamoudeh who took refuge from Beit Lahia in the northern Strip and ended up in a school in Deir al Balah. Hamoudeh had dreamed of starting an art center in her home where she could exhibit her artworks. However, Israeli missiles destroyed her home and all her works. Instead of starting a gallery there, Muna has begun drawing murals on the walls of the school where she took shelter. During such horrific circumstances, art is perhaps the last thing one thinks of amid a televised genocide. However, it has been taking place in tents and shelters. For instance, artists Basel El Maqosui and Maisara Baroud have been producing art with simple materials. El Maqosui, who recently left Rafah due to the Israeli military offensive, provided space and art tools during his refuge and hosted groups of children for art activities. In posts he shared on social media, he revealed, “I draw to remain human, sensitive, and awake, so that the war doesn’t claim my humanity and dignity.”

Ironically he also describes the places where he takes refuge as art residencies. On his last displacement he said, “We are leaving from the ‘Rafah residency’ to ‘Deir al Balah art residency.’” Baroud has also been prolific in drawing his series, I Am Still Alive, through which he kept drawing and posting on social media to inform friends of his survival each day. Baroud had to evacuate Rafah with thousands of others while his drawings circulated around the world from, Gallery Zawyeh of Ramallah in the Occupied West Bank to Palazzo Mora in Venice.

These stories are a brief glimpse of daily life in Gaza where Palestinians find their way to creativity in harsh and unacceptable human-made conditions. From creating new tent structures to establishing education initiatives to making art, Gazans practice daily life in extraordinary circumstances. Such practices, as many Gazans have expressed, are not an acceptance of the new refugee reality, but rather a reminder that returning home is essential to practice these activities and many other ones in dignity.

These “home” activities are in some ways manifestations of the words of Gazan poet Mosab Abu Toha:

What is home

it is the shade of trees on my way to school before they were uprooted.

It is my grandparents’ black-and-white wedding photo before the walls crumbled.

It is my uncle’s prayer rug, where dozens of ants slept on wintry nights, before it was looted and put in a museum.

It is the oven my mother used to bake bread and roast chicken before a bomb reduced our house to ashes.

It is the café where I watched football matches and played —

My child stops me: Can a four-letter word hold all of these?