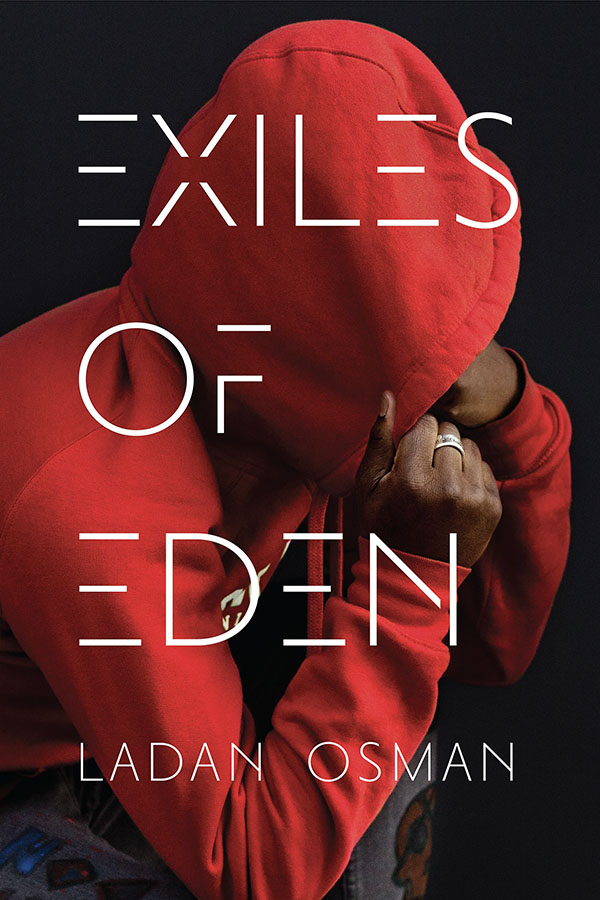

Somalian American poet Ladan Osman presents her book Exiles of Eden, which looks at the origin story of Adam, Eve, and their exile from the Garden of Eden, exploring displacement and alienation from its mythological origins to the present. In this formally experimental collection steeped in Somali narrative tradition, Osman gives voice to the experiences and traumas of displaced people over multiple generations. The characters in these poems encounter exile’s strangeness while processing the profoundly isolating experience of knowing that that once you are sent out of Eden, you can’t go back.

Ladan Osman

The sea fell on my house

The sea fell on my house

I was sweeping

and counting my cups

and rinsing my toothbrush and bracing my hinges

when the sea fell on my house.

The sea fell on my house

when I’d braced for a straight-line wind.

The sea fell on my house

and I couldn’t tell if it jumped on me or me in it

but I was filled with the minerals and matter

every beast and root on earth contain.

I couldn’t tell if it jumped in me or me in it

but I watched it fall out of my body

warm seawater from my body

onto the kitchen floor I’d just checked

for the earth-dust of winter

the brown dust of winter.

When you enter with it

don’t say, “May.”

say, “Can. Can I?”

and I’ll answer with a gesture.

Cover me with your body.

In the atmosphere between

our ribs: rain.

Rain containing the minerals

and salve

for every beast and root on earth.

Cover me and cover my cries.

My mouth a cave for the sea

to rush through

your tongue some urchin

assigned to live

off my minerals and matter.

Later, when delinquent,

refuse to move, your belly at rest

your belly a palm on my belly.

Refuse to move until another train passes

and I’ll say, “No” with a gesture.

The sea fell on my house.

The sky was paperwhite.

Just after noon.

An exact white.

Winter-salt crests and froth

on the sidewalks.

That should’ve been a warning

that the sea would fall.

The real one

not the sad sea of a snow

mound resisting spring.

The real one

fell on my house.

I couldn’t tell if pressure

was at the front of my mind

or if my mind got stopped up

underwater.

The sea fell the sea fell the sea fell

on me and I’m at ease

and thirsty

and a figure is made known

a figure made from all the minerals

and matter

of his fellow beasts, the roots he eats.

We are thirsty and at ease

and falling asleep to the mineral scent

of our contribution to the sea.

We are thirsty and at ease

and the chalk and film of the sea

is dry on our thighs and fingers

and in the juvenile curve

under our lips.

We are thirsty and at ease

we are thirsty and at ease

we are thirsty and at ease

we are thirsty and at ease and mindful of our salt

and thirsty and at ease

and resting

and assured of the yield we’ll mine.

Landscape Genocide

My mother walked Liido Beach every morning when pregnant.

I know the mineral scent of seawater wherever I am.

If the sun bakes the metal of earth, if my own damp scalp sweats,

if I hold my hennaed palms to my face.

I have said, “God. There is no god but God” into my metallic palms.

When my blood started, war started.

Ever since the war started, I dye a henna disk on each palm.

I refresh it when it browns, old blood. “God,”

into my mineral palms when the whole street was white sheets,

thin men digging graves night til dawn til night til dawn.

They paused for every single prayer.

An orb of light dragged me through a dim street, lifted me off my feet.

I shouted “This is my light!” and held it tight against my belly.

I was still, beyond known stillness,

a gravity of my own, and still I didn’t light the street.

The last thing my mother promised me was a photo of her,

five months pregnant, at the shore, backlit by the ocean.

“Go at dawn,” she’d say. The water was warmest at dawn.

At dawn, girls went to the sea in whatever they were wearing,

even if they had school later. Their mothers couldn’t keep them

from the water, from walking fully dressed into it.

There was nowhere to go but Liido.

The orb, a giant marble in my diaphragm would float with me there.

There was nowhere to go but into the sea.

Between this interior desert and the sea at the edge

of my known world, orange pekoe-tinted sand

marked with the heels and balls of firm and dazed feet.

Charred acacias facedown in the dust.

Succulents marking clusters of graves. Graves of people

and fruit-bearing trees. Bones of tall livestock,

the startling domes of camel ribs lit like a great hall

by the relentless sun. There is nowhere to go but the sea.

Between here and its mineral scent, bones of people,

small and not small, bush lions and their young,

always litters of bones at the line between known

and wild worlds. Between here and Liido, the land

in full prostration. The only song, metallic. Shells,

or whole bullets underfoot, sometimes whole piles

at the edge and center of towns put facedown

at night, at dawn, during afternoon prayer, at dusk.

Between here and Liido, the land and everything in it

in full submission to the mineral scent of our water

and blood and inability to cry anything,

not even “God! No god but God!” We go at dawn.