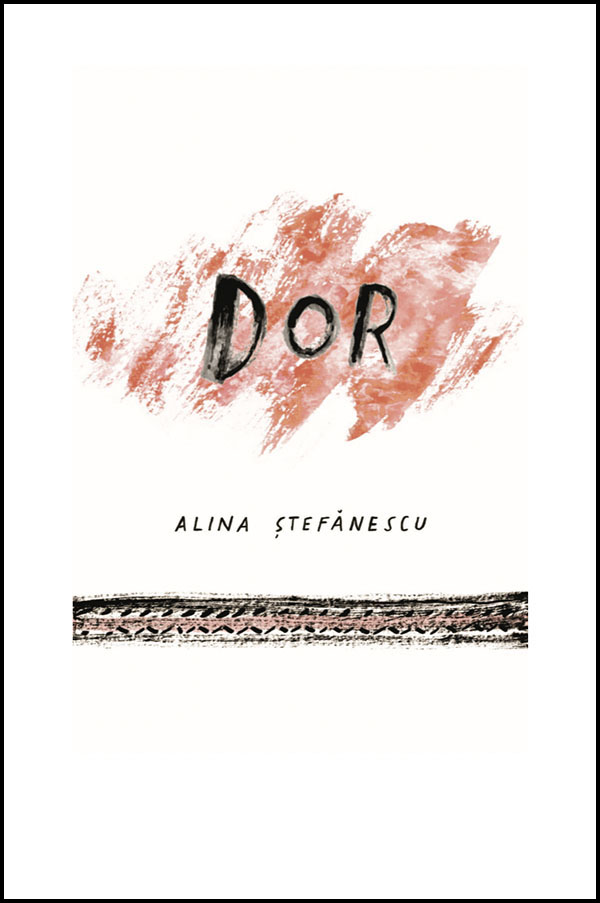

Romanian American poet Alina Stefanescu describes her new book Dor and present the poems “Playing Possum” and “My Polish Child.” As Emily Holland writes, “DOR is a compendium of desire, displacement, longing, and belonging. While the word ‘dor’ itself ‘serves as a bridge which creates its own territory from fusion,’ here Stefanescu’s words do their own act of bridging the spaces between the body and language.”

Alina Stefanescu

Playing Possum

This is my mother, newly-dead, Mom says. She died without suffering.

I fondle the photo of my maternal grandma playing possum.

A dead possum in a ditch is called roadkill.

A possum who’s just playing is not yet carcass.

The women in my family will play anything to make you wonder.

Just to see what you’d say about us then.

The woman in the photo is my namesake.

The photo taken by the man she met and married in med school.

It was he who administered the final morphine injection

when breast cancer claimed her brain. He did this

without telling their daughters. He consulted none, invited

none into the living room of the Transylvanian cottage

he drafted and built by hand. It was her green dream-house.

He did it because she wanted to remain herself.

She made him promise. She made him promise again.

She said if you love me….

He signed her request with a blue fountain pen

from Czechoslovakia. The contract hid among papers, letters,

photos he preserved, images of her naked breasts, arms raised

above her head, his Alina—winsome, hungry, amorous,

and finally, finally, faceless two gray hands

locked in languor over her chest. An orthodox cross

laid over v-shaped limbs, a flock of birds on their way to the Danube.

I am an atheist now, he announced.

But no one believed. None believed a man who hated god so faithfully

could ever come to disbelieve Himself. This was Ceausescu’s Romania.

The dictator ruled from posters with iron fists. I know hate and

hope are kindred, knit through our palms. And these lines

in my hand: a silenced mutation.

My Polish Child

I lost a child on the streets of Krakow.

Somewhere near the center of the square,

women queued with pigeons.

The ending I wanted

was illegal.

My cousin came on a train

from Romania.

Like an accordion winding down a carnival,

we tried

hard to find the absent word. Loss

layered like velvet curtains

round our lips.

The cathedral held a rat

in reserve, its eyes approaching vermillion.

I felt a color. Not an expression

of life.

Stones steamed with the imprint of ancient chariots.

I crossed my heart, told my cousin: we have always

been running, letting the next breath escape.

A couple ended an argument under neon. I held tight

the ticket. What happened is unlikely

to explain. I must have carried it

wrong.