In January, the fires of southern California, wild and manmade, ravaged the southland as never before, creating thousands of new homeless refugees and billions in property damage. Many of our friends — musicians, writers, artists, filmmakers et alia — lost their homes. Our contributing editor Francisco Letelier has been here before, and connects the devastation of climate change with the decimation of Gaza, and other disasters over time.

In January 1959, I was in my mother’s womb when an earthquake struck the central coast of Chile, causing widespread mudslides and fires propelled by hot eastern puelche winds coming off the Andes (puelche means east in Mapudungun, the language of the Mapuche, the largest indigenous group in Chile). In May of 1960, another, stronger earthquake struck. Measured at 9.5, it was the most powerful earthquake ever recorded, causing a tsunami that devastated the coast of Chile and unleashed damage across the Pacific to Hawaii, Japan and the Philippines.

My grandfather, Alfredo Morel, died before I was born, and my mother told me about the great sadness that accompanied us during my gestation. I was born between the shaking that presaged her father’s untimely death and the “big one” that predicted our departure from Chile. My father lost his government job when the conservative regime of Arturo Alessandri culled opponents from its ranks and we left in search of a new life in the United States. I was less than a year old as we entered New York Harbor on the Santa Rosa cruise liner and made our way past the Statue of Liberty.

When the Santa Ana winds begin in Southern California over the fall, I feel their particular power. The continuing destruction, death and bombing in Gaza and the subsequent election of Donald Trump has pushed me into a silence of deep grief and anger that finds me retreating to the shelter of the surrounding mountains.

Early in December 2024, I come down with the flu. A few days later, I think I’ve recovered enough to take a hike up Santa Inez Canyon in the Santa Monica Mountains, above Pacific Palisades, a neighborhood of Los Angeles, but I soon turn back, feeling feverish on the way home.

The legendary Santa Ana winds are sometimes called “devil winds.” Dry and desiccating, the winds affect behavior and mood. Besides dust and embers, the wildfire-instigating winds also carry spores and fungus that can lead to valley fever, an illness that presents in a host of flu-like symptoms, including rashes and pneumonia.

During the holidays, as I try to sooth my lungs, I think of Bethlehem, refugees and fire; it’s a less than joyful holiday. As the Santa Ana winds blow, they bring an unquenchable bout of cold coastal fog, even as the hot winds heat and dry the neighboring hills and mountains. I develop bronchitis and soon I am diagnosed with pneumonia.

Slowly recovering from my illness, I am on the beach at 10:30 am on January 7, 2025. It’s low tide in Venice, California, and the winds are picking up, when towards the northeast, I notice a plume of smoke in the mountains. In only ten minutes the column grows larger. At that distance, a few miles away, the flames seem to be almost a hundred feet high. I can’t pinpoint the location, but calculate it’s a place I know well. I make a short video with my phone, guessing the fire will be historic. The fire predictably grows with the increasing winds, covering the horizon with billows of smoke

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area covers 153,075 acres, and is the world’s largest urban national park. I have a forty-year long relationship with its trails, chaparral and forests. I go there often, including yearly trips with my sons to an isolated place where we renew our relationship to the earth and one other.

Los Angeles has communities from all over the world. The original inhabitants, Kizh (Tongva), Chumash and Tataviam, lived in this place for centuries and are still here. The city of Nuestra Señora de La Reina de Los Angeles was founded by a small group of 22 people in 1781: two were black, two were from Spain, four were indigenous from Mexico and the rest were multiracial combinations. The people living in the city today look much like the founders and original inhabitants, and the vast majority of us understand the notion of refuge. Los Angeles, Santa Monica and other places in California are sanctuary cities in a sanctuary state, limiting cooperation with federal immigration authorities and prohibiting city resources from being used for immigration enforcement. Soon many of us will be seeking some type of refuge.

The Palisades Fire is not the only fire that is ignited on that day. The Eaton Fire ravaged the city of Altadena at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains, a place recognized for its cultural diversity, with a long-established Black community where many artists live. The Altadena library, through efforts of community members and firefighters, is still standing.

The last time I saw my friend, Black writer Peter Harris, was at the Altadena library. A National Book Award winner, Peter was one of the poet laureates of the city when he died last fall. I translated into Spanish and illustrated one of his last books, Safe Arms, Twenty Love and Erotic Poems, inspired by Pablo Neruda’s, Twenty Love Poems and Song of Despair. Neruda, the Chilean Nobel Prize-winning revolutionary poet was poisoned by the military rulers of Chile in the months after the 1973 coup that led to my family’s second exile. There is never a guarantee of the future, but while alive, Neruda crafted a vision of the Americas driven by geography and acknowledgement of our indigenous roots while honoring the many cultures that populate the Americas. Neruda was inspired by our mixed ancestry and certainly celebrated the population of Palestinians in Chile who are part of our inherited national identity. The 500,000 people of Palestinian descent make it the largest population of Palestinians outside the Arab world. Both Neruda and Peter Harris knew that the identity of the American continents is an ever simmering battle with lines of skirmish that move like storms from Danish Greenland (yes, it’s a part of North America) through Canada, and south through a diversity of cultures, geographies and histories.

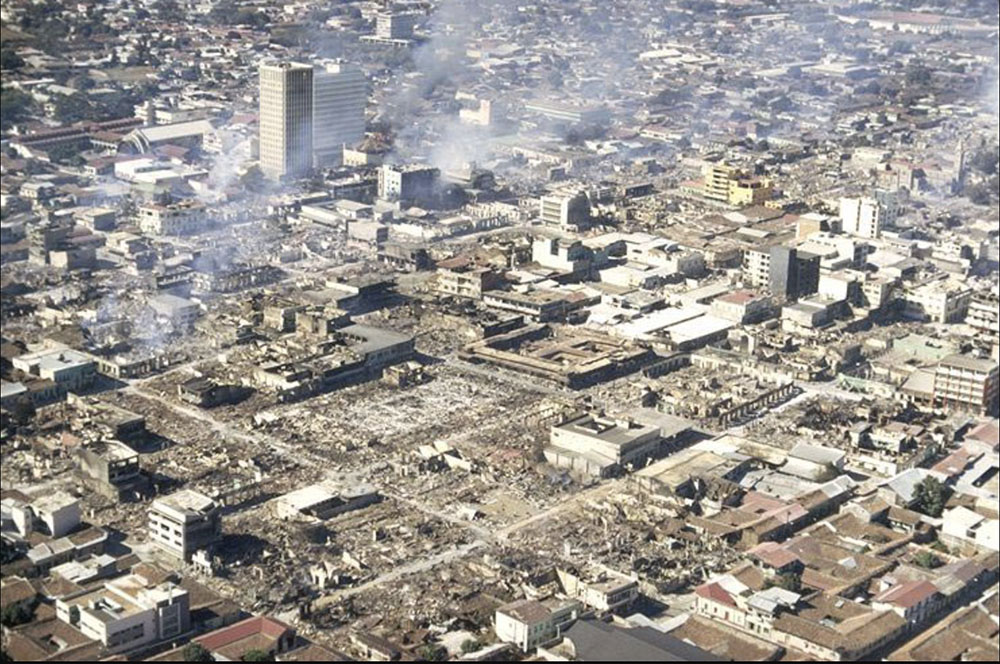

As we land in Managua, Nicaragua, we see miles of rubble and smoldering fires. The 1972 earthquake destroyed the city in 30 seconds and cracks run the length of the runway. I am 12 years old, flying from Santiago to Washington DC after a winter visit in Chile. The Chilean air force plane, sent by the socialist government of Salvador Allende, is loaded with relief supplies for the people of the destroyed city. Homes, mostly built from Taquezal, a construction system in which a cane frame is filled with stones, mud, and grass, have all collapsed. 10,000 people have been found in the rubble but the death count is higher and the smell of death lingers in ruins and the airport tarmac.

At this time, Anastasio Somoza is the man in charge of the country, part of a family dictatorship and dynasty founded by his father that has lasted almost 40 years. International aid pours in after the earthquake; even the Chilean government that opposes Somoza does not hold back in helping the people of Nicaragua; there are no conditions. Later the world learns that Somoza as head of the National Guard and of the National Emergency Committee has allocated the funds and supplies to himself, his friends and family and virtually nothing to the victims of the quake.

After unloading, the plane makes two terrifying aborted attempts to take off. We have taken on new passengers and baggage, making us too heavy to gain the speed needed to lift off and clear the surrounding hills. Ironically, the new passengers are soldiers, freshly trained at the Panama Canal Zone by US advisors. In another 18 months, under orders from their military leader, Augusto Pinochet, they will kill, imprison and subjugate the government and supporters of Salvador Allende. On the third attempt on the crumbling and shortened runway, the plane barely makes it over the squat flight tower.

The discontent over a promised rebuilding that never takes place is only one of the reasons why the Sandinistas National Liberation Front gains the support to launch military initiatives against the National Guard, liberating the country in 1979. 35,000-50,000 persons die in the Nicaraguan revolutionary war.

Concerning US support for the 43-year Somoza dictatorship, in 1939, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said of the first Somoza: “He may be a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch.”

I return twice to Nicaragua, painting murals with fellow Chileans as part of the Sandinista National Literacy campaign and later with a Chicano delegation of muralists from Los Angeles. On my last tour of Managua during the covert Contra War funded by the United States, I catch dengue, a disease carried by mosquitoes. Dengue’s common name may come from the remnants of “evil-spirit sickness” in Swahili, ka-dinga pepo. But in Nicaragua, dengue fever goes by Quebranta huesos — “break-bone fever.” I almost die.

Dengue was not endemic to Nicaragua prior to the clandestine war and many suspect it was introduced as a form of warfare. 17,400 cases of dengue are reported in Nicaragua in 1985. Afterwards it spreads throughout Central America and other countries, including the United States.

Those who witness the US wars in Central America return to Los Angeles and other places like a fugitive wind, determined to kindle bridges of understanding. What we witness and how we respond might determine the future, but the effects of war follow us relentlessly there.

Seasonal fires spurred by the annual Santa Ana Winds in Southern California race down canyons and into places people make their homes. It’s nothing new, but with changing climate and drought conditions, fires have become more severe and destructive. It is sensible to bemoan the loss of an agricultural zone that once stood between urban development on the coast and the mountain born winds. Until the 1950s, LA County was the top agricultural county in the United States; everything was grown nearby. The zone is now gone, with housing developments stretching in every direction. Los Angeles has relied on water from other places for more than a century. The California Aqueduct transports water over 400 miles from the Eastern Sierras, and from the Colorado River through the Colorado River Aqueduct. Only a third of the water is groundwater pulled from beneath the surface. Over time, all sources are rending less.

I often use materials gathered in nature in my work as an artist. My relationship to the earth helps me endure this city, this country, this planet, this time. Today, smoke drifts from the mountains, and at night the glow of embers accompanies the ash. The images of ruined buildings on the news could be from anywhere; the fires have destroyed an area the size of Paris.

![92 percent 436,000 of housing units in Gaza are destroyed or damaged, in addition to 80 percent of commercial facilities. [Mahmoud Isleem Anadolu]](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/92-percent-436000-of-housing-units-in-Gaza-are-destroyed-or-damaged-in-addition-to-80-percent-of-commercial-facilities.-Mahmoud-Isleem-Anadolu.jpg)

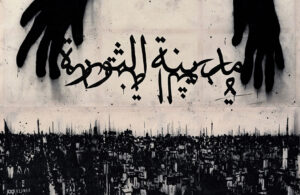

It’s hard not to think of the destruction and death in Gaza. There, the hot Khamsin east wind from the Arabian Desert shrivels plants, but it is nothing compared to the fire that now falls from the sky. In the unimaginable ruins, the east wind that blows in winter is as dangerous as the summer wind, bringing a chilling cold to people now living in tents with uncertain supplies of food, water, and heat.

In the past I carried “contraband” into youth prisons throughout Los Angeles County. They were materials that were regulated and proscribed. To my incarcerated and sometimes handcuffed students, I would explain the medicinal benefits of white sage and how it controls insects. Showing them fossils and agates, deer horn and pieces of driftwood, we’d create dream pillows filled with mugwort plant, craft dreamcatchers from willow, and weave cordage from yucca fibers, all materials gathered in the mountains. Many of the young people I worked with had never been in nature, only seen pictures of places just a few miles from their homes.

In the village of Bil’in on the West Bank of Palestine, travel is restricted; to get even a few miles away imposes a series of checkpoints and barriers most will never pass. In murals we paint the longing of people to travel to Jerusalem. Enclosed by barrier walls, there is no refuge, no place of safety. Thistle and stones, orchards and sky witness embers as old as the Nakba in the open-air prison. When Israeli forces surround us in the olive orchards of Bil’in, there is no place to retreat. Soldiers lob teargas cannisters from many directions.

In Los Angeles, as the fires grow, thousands are displaced, and we listen for mandatory orders and warnings of evacuation. Curfews are established.

The billions of dollars pledged to Israel by the United States have enabled firestorms daily for more than a year in Gaza. Creating infrastructure that responds to increasingly deadly weather patterns caused by climate change and fueled by greed would be a better use of resources.

The footage of the conflagration is terrifying. 100 mile an hour winds carry embers that light fires anywhere they land. We race to help evacuate family and friends. Smoke leaves us red-eyed and sick as we watch the news. The skies are dark. We are in shock; it’s impossible to take it in all at once. Many of us recognize the desperate and determined conviction of a mountain lion and two cubs, recorded on Topanga Canyon Blvd, singed and blackened from smoke, escaping the fires.

Our bits of wild are precious; they tie us both to the earth and to our shared humanity. When I am within the mountains, I am not in Los Angeles or the United States, but in a nation without borders, defined by what actually exists, despite human interventions. Those who love the earth understand that the vast majority of humans are interlopers, no matter our stripes. We do not speak Coyote, know no words in Sycamore, do not understand the language of olive root or desert lichen and have forgotten how to listen to the wind.

Santa Inez Canyon is now immersed in the flames of the Palisades fire. Years ago, I once heard a soft patter along the trail there. I jumped into the dry creek bed and saw a mountain lion.

I am very close to it. With its back towards me it moves like an eastern breeze, its steps creating a muffled rhythm in the fallen leaves. He has no tracking collar and perhaps it means that no wildlife wardens have ever seen him. He is an older male, his coat scratched and scarred. Skinny, with a distended belly, he seems absolutely aware. Deer inhabit the wooded corridors here. When he looks at me for the briefest of moments I can tell he isn’t interested, he’s after other game. Vulnerable, he is a survivor looking for shelter. I stand in the dappled light of oaks and sycamore and he walks out of sight. The only other lion I have seen so closely was in the far Southern Patagonia of Chile. Now, I feel my true home must be somewhere between those cats, between nature and disaster, searching for safety despite smoke and ruins.

In Los Angeles, it is said that nothing lasts. Buildings are torn down, demolished and built again. Places that have been rebuilt abound in California. Valparaiso in 1848 is the major port on the Pacific when news of gold in California arrives. Chileans are the first to hear the news, and carpenters, miners, speculators, and prostitutes all head north. During the Gold Rush, Chilean hands that know ships and lumber help rebuild the boomtown of San Francisco. Plagued by wind-driven fires it burns to ashes several times. On the heels of the Mexican American War, groups of nativist, anti-foreigner gangs known as The Hounds, lynch and hunt through communities of Chileans. Today some names echo the forgotten Chilean roots of the state I live in, but that memory has virtually disappeared.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire lasts four days leaving 80% of the city in cinders. That same year of 1906 the port of Valparaiso, Chile experiences earthquakes that unleash destructive firestorms. Brigades of firefighters are formed, many by colonies from Europe. Italians are decorated for their bravery. Civic groups and volunteers join in an international effort to rebuild.

We have only just returned to Chile, when in 1974 we enter exile the second time, escaping the Pinochet dictatorship on a ship out of Valparaiso. I try to return to live in my country a few times, during the dictatorship and afterwards, before I grasp that my home will be rebuilt in another place, with relationships and children born and forged in other fires.

After the Woolsey Fire of 2018, ridges within Topanga Sate Park are left bare and a fire cut used to contain the fire is now disappearing in sprouting chaparral. Following the cut, there is a rocky point, normally so thick with brush it is unseen and impossible to reach. The sandstone beneath is blackened by fire and full of fossils. The Topanga formation is around 20 million years old; the mountains are only around four million. It is rich with fossils, and contains a wide range of fish, sea lions and whales. Another ridge over, the Sespe formation is revealed in Red Rock Canyon. Some of the rocks formed more than 66 million years ago and contain mollusks and microfossils.

There is a staggering amount of undiscovered history out there. On the furthermost outcropping, an overhang of sheltering rocks protects ancient native grinding holes. Sometimes we are able to get a glimpse of time and people in places we once took for granted.

It is believed the Palisades Fire originated on a ridge of Temescal Canyon.

Temescal is the word for sweat lodge in the Nahuatl language of Meso-America and translates to “House of heat and steam.” In 1994, primatologist Jane Goodall visits the canyon to inaugurate the Snake Mound, an earthwork sculpture I and others create with hundreds of students from Los Angeles County. African drummers, Mayan botanists, teachers and community members turn out to support an effort that joins us globally to projects sponsored in Africa by the Jane Goodall Institute. Under a majestic sycamore tree near Temescal Creek, Dr. Goodall buries a time capsule with various messages sent into the future from children and community figures. Now the fire moves through the canyon and up the hills surrounding the site. The capsule might still be in the ground, and the magnificent tree still standing, but if not, on that day we created a memory now infused into its smoldering ruins.

In Bil’in, on the West Bank, I find a trail through crumbling sunken walls to the ruins of the old mosque. No one is there; it is a silent and abandoned place. Potsherds have been found on these grounds from ancient Greeks, the Roman Empire, the Crusades, the Ayyubid dynasty and the Mamluk and Ottoman periods. There is memory and forgetting within the ruins. In a collapsed alcove, I don’t investigate what seem to be bones. Charred cannisters of tear gas appear in the rubble.

It is hard to convey the devastation that surrounds us now, and many continue to incur great losses. Our home in Venice is full of evacuated people. My partner’s parents are great grandparents, and live only a few blocks from the fire, but are now here with us. My son’s mother loses everything when her cottage in Pacific Palisades is burnt to ashes. Both the elementary school and high school once attended by my son are devastated. Everyone knows someone who has lost a home or is currently displaced.

The blaze continues to burn through chaparral and forest, where my animal teachers — lions, coyotes, deer, owls, and hawks, snakes, frogs, and amphibians, hummingbirds and countless birds — once dwelled. They are homeless now, as so many were before this fire, and as are thousands more now who have lost everything.

It’s true, we’ve seen this kind of thing before; there have been bigger fires and greater disasters, but for those who live, dream and struggle here, this is not just another fire. We will feel this for generations. Many have lost their homes but thousands of others their livelihoods as well. Those who incur loss are also those who work, build, garden, and cook in the places that now burn. Our memories and love and livelihoods are instilled into places our hands have touched.

A friend writes me from the island of Réunion east of the island of Madagascar to inquire about my safety. The images of the fires here in Los Angeles reaching her island home remind her of the thousands who lost their lives last month on the islands of Mayotte, on the other side of Madagascar when the Chido Cyclone devastated everything. Before her message I knew very little about it.

A little more than a year ago, beginning on February 2, 2024, fires descended from the hills and through the stream valleys that run through the cities of Viña del Mar, Valparaiso, and Quilpue on the central coast of Chile. Racing into residential areas and neighborhoods, the fire covered 112 square miles and damaged or destroyed more than 14,000 buildings. According to the International Disaster database it is the fifth deadliest fire globally since 1900. Drought, heat, and high winds create a fast-moving wildfire that is exceptionally dangerous and almost impossible to fight. Conditions are worsened by eucalyptus plantations that provide lumber and short term gain, but outcompete with native trees and plants for water. Hit by flame, they go up like match sticks.

It’s the kind of fire that is increasingly frequent across the globe.

Sometimes, arsonists cause fires; or lightning or human accident. In other cases, leaders and public agencies foment conditions that lead to crisis and riots. On April 30, 1992, I also wake up to smoke and flames. The 1992 LA uprising, after the Rodney King verdict, results in riots and fires through swaths of the city. Long held anger over police violence spills into the streets. We live through that time knowing that a people held by a police force and subjected to oppression for generations may rise up in violence and anger. Under those conditions, fires will break out, becoming wilder and more unmanageable, creating generational harm not only for the occupied but also for the occupiers.

Budget allocations to the fire department in Los Angeles are under scrutiny, but more funding would not have created the systems needed to fight the Palisades Fire; they do not exist. “Municipal water delivery systems are not designed to handle fires like the Palisades Fire,” says a Fire department spokesperson. “It’s impossible to fight fire on the ground along ridges and canyons when dry fuel ignites across 35 square miles, and 80 mph winds create a cyclone of flame and embers. Even the planes and helicopters that drop water and retardant cannot fly in high winds and smoke.”

Some are ready to return and rebuild, others have nothing left and insurance companies will not cover their losses. Some may leave, but these conditions are everywhere and cover the map of the world.

As President Trump comes into office, the workforce of immigrants that would carry out the rebuilding is under attack. Only last week, 531,000 DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipients, the children of parents who entered the country illegally, suffered a setback when a federal appeals court ruled that an Obama-era amnesty program was unlawful. Others who have relied on birthright citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment are also threatened. Upon taking office, the incoming president has vowed to prioritize doing away with birthright laws and to begin the process of deporting “millions and millions.”

In 1848, Mexico lost more than half its territory to the USA when the Treaty of Guadalupe ended the expansionist Mexican American War. A century later, in 1948, the creation of the State of Israel was proclaimed. US President Harry Truman recognized Israel on the same day. Just as Palestinians have not disappeared, many mestizo, native and other people who inhabit the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming, remember the past and are in constant struggle.

There are those who suffer everywhere, and some live under conditions of violence and genocide over generations. Life is not a competition of pain and suffering, but neither is it a race towards happiness; nature shows we are best when we are in balance. What we pay attention to can depend on more than which way the wind blows. Living on a planet with a climate changed by our human societies, we can recognize the places where we can exercise judgement, apply the law, and remedy suffering.

Winds and wildfires are not bombs and rockets. In the fog of smoke and storm they might be easily confused. No one controls the clouds and wind, but some speculate on land and homes while water rights are sold and negotiated, without the participation or wisdom of rivers, trees, bees, people or history.

Profit is not a crime. In LA, real estate agents are already actively pursuing profit and local government has stepped in to control rent gouging. All is fair in business or after disasters. Rebuilding becomes a catchword for business opportunities and crisis always favors those who exploit the suffering of others, here, there, everywhere. In the hills of Los Angeles, in Palestine, in Lebanon, in the Sudan, in Chile and in California’s Central Valley, it is not a local management problem, it’s a fundamental issue we all share as human beings.

The world is burning in many places, but sadly many think they are the only ones who confront challenges. Others want to point fingers, but the wind and heat belong to no one in particular today. They create ash, they scar hearts and neighborhoods no matter the race, bank account or belief. Wherever you are, hold your loved ones close. Here at home we are alive, safe and well for today, and in today’s world that is a lot.

At the end of Sunday, January 12, after six days of growth, the Palisades Fire is reported to be largely in check. Significant gains have also been made in containing the Eaton Fire to the east. It is a beautiful sunny day in Venice, with clear blue skies, with only a faint smell of smoke, although eddies of ash cover all outdoor surfaces. The wind is picking up and even though increasingly under control, the threat of renewed blazes remains high. Flurries of white particles drift in the waning light of apocalyptic orange sunset skies, as we prepare for the return of high winds in the coming week.

The fires are made worse by decisions taken decades ago and ways of life that can lead to worse conflagrations, but communities all over Los Angeles show incredible organization. Volunteers are of all ages, races and walks of life, and there is an outpouring of donations of both money and time. Many countries lend a hand; it’s an international effort.

An indifference to what happens to others is not uncommon. Some don’t care about hostages, others are not troubled by the deaths of innocent civilians, women, and children. Some care only about the poor, and hold a special disdain for the rich. No one will know the names of myriad victims in places far away, but here movies, television and media are a local industry and it’s likely that funding campaigns, podcasts, movies and miniseries will memorialize and echo the destruction and the names of the fallen.

Nonetheless, we all breathe air that is increasingly toxic. All of us rely on threatened and contaminated water supplies. The salt water and fire retardants used to douse flame leave behind a poisonous miasma of rubble that affects us all.

We leave many things behind in life, carrying phantoms that both haunt and push us forward to build a world that will contain us. From this place of loss some will create bridges across earthquakes and fire, across bombs and struggle. How much do we have to lose before we recognize each other in the flames?

For the rest of January during a rare celestial phenomena seen only once every hundred years, the planets will align in the night sky. Here in California against the horizon at twilight, I can see Jupiter, Venus, Uranus, Mars and Saturn with the naked eye as the sun sets in the west. In a week or so, Neptune and Mercury will join the parade but shortly the show will drift as the planets continue their orbital journeys.

Our old ways of looking at the world were built for a climate we no longer have. I imagine a system that understands we are traveling through space alongside other worlds that we often cannot see. Although some think we have things figured out, there is much more we have yet to learn.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

Loved reading Francisco Letelier’s piece, an ode to a meaningful life well lived.

What a powerful account of so many periods of history. Personal accounts by Fransisco leaves me feeling, smelling, tasting and touching the fire and ashes. He teaches us to recognize our interdependence.

Francisco such a comprehensive moving piece! We all live in the shadow of history. Thank you for your deep heart and beautiful writing. I too feel the connection to those devastated by war much more personally now that I have lost my past to this fire.

Wonderful, poetic and crude as the realities he describes…..inspiring and prophetic !!!