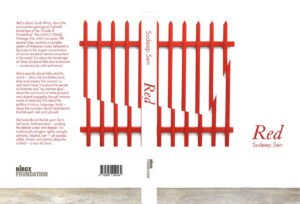

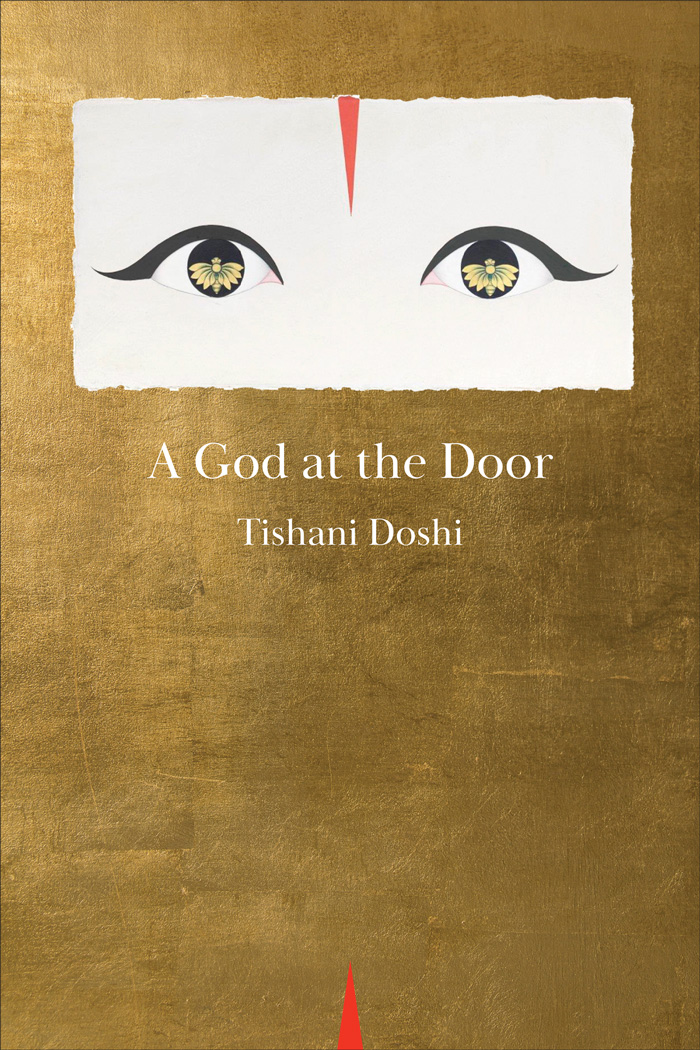

A God at the Door, poems by Tishani Doshi

Copper Canyon Press, 2021

ISBN 9781556594526

Survival

Dear ones who are still alive, I fear we may have overthought

things. It is not always a war between celebration and lament.

Now we know death is circuitous, not just a matter of hiding

in the dark, or under a bed, not even a slingshot for our loved

ones to carry, it changes nothing. Ask me to build a wall

and I will build it straight. When the end came, were you

watching TV or picnicking in a field with friends? Was the tablecloth

white, did you stay silent or fight? I hope by now you’ve given up

the fur coat, the frequent-flier miles. In the hours of waiting,

I heard a legend about a woman who was carried off by winds,

a love ballet between her and the gods, which involved only minor

mutilations. How I long to be a legend. To stand at the dock

and stare at this or that creature who survived. Examine

its nest, marvel at a tusk that can rake the seafloor for food.

Hope is a noose around my neck. I have traded in my rollerblades

for a quill. Here is the boat, the journey, the camp. If we want

to arrive we must push someone off the side. It is impossible

to feel benign. How many refugees does it take to build

a mansion? I ask again, shall we wait or run?

Here is winter, the dense pack ice. Touch it. It is a reminder

of our devastation. A kind of worship, an incantation.

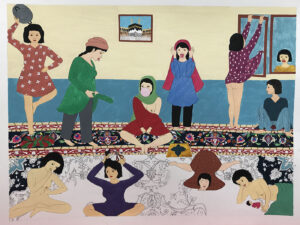

After a Shooting in a Maternity Clinic

in Kabul

No one forgets there’s a war going on,

but there are moments you could be forgiven

for believing the city is still an orchard,

a place where you could make a thing grow.

There is always a pile of rubble from which

some desperate person struggles to rise,

while another person wraps a shawl

around their shoulders and roasts

marshmallows over a fire.

This is not that.

This is not bomb dropping from sky,

human shield, hostages in a stream, child

picking up toy that explodes in her hands—

although there’s always that—hope is a booby trap.

This is the house you were brought to after crossing

a river, leaving the mountains and burnt fields

behind. A place of safety where you

could be alone with your own

startling power.

Not Why were you out? And why

wasn’t your face covered? And who told you

to climb into that rickshaw? But Here, prepare

for this most ordinary thing, a birth. And this is not

to ask what it means never to see someone again,

but to ask what it means not to make it past

the first checkpoint of your mother’s gates.

Never mind all the wild places

outside—

the mud-brick villages, the valleys and harvests

and glasses of green tea. Or even to say I am here

to claim the child of Suraya, because you know

this to be impossible. Even if you could bring a man

to recover your sister’s corpse and the newborn,

where do you go from here? You still have

to consider the bodies, the bullet-ridden

walls, still have to find the small

window of this house and take

in the panorama.

See—it is raining outside and men weep

for their wives, and perhaps the entire world

is an orchard that has detonated its crimson fruits,

its pomegranates and poppies and tart mulberries

to wash these floors red, and those of us who stand

outside this house know that nothing will flourish

here again. Like crowds who gather

for an execution, we can only ask,

what does it mean to be born

in a graveyard, to enter

the world, saying,

Oh thief, oh life.

Self

And when they ask what kind of animal

would you be, I always say gazelle or lark,

never cockroach, even though they’ll outlast

us all. Once I dreamed I had a body with two

heads like those ancient figures from the Zarqa

River—bitumen eyes, trunks of reed and hydrated

lime, built thick and flat without genitals, nothing

shameful to eject except tears. We all want to be

monuments but can’t help shoving our fingers

in dirt. Imagine a life in childhood—one face

to the womb, another to the future. What we remember

is the road, peering through a lattice at dusk,

the trauma of burial. Will we have terra-cotta

armies to take us through, will we be alone

with the maggots? How good the rain is

after a failed romance. Never mind the muddy

bloomers. We are appalled by life and still,

any chance we get we emerge from the earth

like cicadas to sing and fuck for a moment

of triumph. The shock we carry is that the world

doesn’t need us. Even so, we go collecting parts—

an afternoon by the sea, a game of hopping on

and off scales, nose low to the ground, looking

for that other glove to complete us.

Here I am, globe, spinning planet.

Tell me, Why are you not astonished?