I learned to live in pain. I sometimes wondered if the specter of global capitalism was a ghost who haunted us.

Ahmed Awadalla

At one of the work meetings, a colleague suggested an icebreaker. The colleague, a middle-aged German woman who spoke slowly and deliberately, suggested we talk about our first job as a bonding exercise. “We will discover something new about each other,” she said, her tone sounding like she had achieved a breakthrough. “Mention the job and what you learned from it,” she triumphantly added. An idea that, to my surprise, found instant appeal.

I was working as a social worker at a sexual health center in Berlin. Despite our mission to help and support people in vulnerable positions, I felt that the collegial relations were rather, let me say, icy. I was the only non-German at the office. My German was acceptable but limited. This meant I had to perform extra layers of invisible labor to overcome the language and cultural barriers. My colleagues nodded approvingly while I tried to hide my frown. I started to wonder if I indeed was the problem.

I balked at the exercise; it felt like one of those questions that often happen at the beginning of a conversation with a stranger which is meant to assess the other and put them in a box. “Where do you come from?” put me in the Middle Eastern geopolitics box, and “What do you do for a living?” puts people in a class and income box. The activity didn’t seem specifically creative or delightful. I felt, then, that perhaps I wasn’t the problem after all, but rather that this was a platitudinous attitude and obsessive desire to classify and assort. In any case, I had no option other than to join the stern smiles and play along.

The First-Job Circle of Confession opened with a colleague, who worked as a bartender and said something about the social skills he developed by interacting with drunk people. As I tried to think of an answer that was both brief and meaningful, I had a Kopfkino going through my mind:

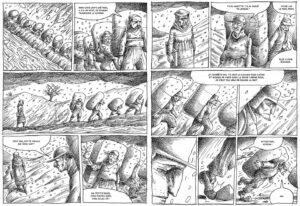

The cars dash across Salah Salem Road, one of Cairo’s main arterial streets, connecting its west side to the east. Congested by day and freely flowing by night. It was a few minutes past midnight. I had just finished my work shift and hastily packed my things to go home. I need to get to the other side to take the bus back downtown. This section of the road is dimly lit, and the drivers don’t hold back their speed. A pedestrian crossing simply doesn’t exist. I stand on the pavement, taking deep breaths, preparing for a crossing — a game one must master to survive Cairo streets. I feel like a matador dancing my way out of bull’s horns. I hold my breath and make a run for it. In the middle of the road, I twist my ankle. I hear something crack.

Mother will never understand why you had to leave

But the answers you seek will never be found at home

The love that you need will never be found at home

—Bronski Beat

My first job was my visa to move to Cairo from the stifling Upper Egyptian town where I grew up. My father died when I was 13. He was only 47 years old — a loss that I still don’t fully comprehend until now, and I haven’t written about thus far. I just knew that this meant I didn’t need his approval for my life decisions. My mother was the visa officer I had to get permission from. “I am going to find a job in Cairo,” I tried to persuade her. It didn’t make sense to her because life in Cairo is much costlier, and getting a job in our town would save expenses. More importantly, I would remain close.

She said yes, but I felt that she perceived it as abandonment. It is only temporary, I tried to reassure her. This proved to be a big lie. More than 15 years have passed since that moment, and now I no longer live in the country. I moved to Berlin, and I have no intention of a foreseeable return.

I felt selfish to leave my family behind to pursue a better life for myself. I had two younger sisters who were still at school. Someone like me was expected to stay with their family until I got married, or perhaps work to support the family financially. Instead, I left to search for like-minded people, to be able to go to the cinema, I wanted a true urban life. I also wanted to run away.

Growing up queer has shaped me in many ways. That need to excel is a feeling that has accompanied me since I was a child, as if I wanted to make up for something I lacked: my voice was high pitched (though when puberty hit it became muffled), my physique weak, my handshake loose, and my general demeanor shy and reticent. In other words, I didn’t have the classical attributes of masculinity. I had no interest in boy stuff or men’s talk. What I lacked in terms of gender performance, I made up with mental sports. I was a dreamy child who wanted to read books and watch science fiction TV series.

As a teenager, I dreamt of becoming a doctor. I like to think that watching medical dramas when I was young was a turning point. The somewhat unrealistic representations of patient-doctor relationships in American TV shows inspired me. Plus, I often felt sick, by which I mean I carried the burden of being considered sick by societal standards.

I eventually changed course. I decided to study pharmacy instead. Sometimes I marvel at the workings of my mind at that age. I was 16, an awfully early age to make a decision that majorly influences one’s future. I chose to study something I was passionate about (I was a science geek at the time), but I was also making pragmatic economic decisions. Doctors were less employable, and their training required longer years. I was working my way through independence. The plan to leave my hometown had been a project long in the making.

The job would provide justification and yield social approval. I had to prove myself — that is to prove that I could work and live independently. If I couldn’t provide for my family, then at least I shouldn’t be a burden to them. I still felt guilty and knew I would miss them terribly in Cairo, the harsh megacity where everybody seemed to be in a rush.

“Pain involves the violation or transgression of the border between

inside and outside, and it is through this transgression

that I feel the border in the first place.”

—Sara Ahmed

I found my first job through pure chance in the early weeks in Cairo. I was quickly disillusioned by the job prospects available to pharmacists. Pharmacy graduates end up working at a pharmacy, deciphering doctors’ handwritten prescriptions which seemed wildly boring. A more lucrative option was to work as a salesman for the pharmaceutical industry, a job that involved touring doctors’ offices to convince them to prescribe the company’s products. In exchange, they would receive gifts and promises of fancy medical conferences locally and abroad. These pharma representatives received cars and wore handsome suits as part of the job. To me, this failed to cover up the fact that it was a form of bribery. Neither prospect felt right for me.

At the Ministry of Health, people squeezed into crowded offices to take care of their affairs. I had gone there to apply for a pharmacist license. On a wooden announcement board, layers of paper were pinned on top of each other. I noticed an obscure advertisement for a company recruiting medical professionals with a good command of English; medical transcriptionist was the job title. I made a call, got my first interview, and quickly was accepted into the job. There was an initial on-the-job training phase where I would be paid half the salary. I was exhilarated.

When I look back at this now, I realize that the narrative of finding my job through serendipity was an error. It can’t be assumed that everyone who passes by a job board stops, looks, or applies. A certain disposition towards work is required to do so. Some people are more relaxed about finding work, while others hustle more. These attitudes don’t solely hinge upon the extent of wealth one owns, but rather on a complex set of social, psychological, and environmental factors that we sometimes bluntly call class. Social capital exerts leverage, as some rely on their connections and friends to procure employment. Others toss their fishing rods in the dark, hoping for a catch. Sometimes a certain apathy towards work stems from the deep wisdom that work will beget exploitation.

I don’t mean to claim to be self-made. I am trying to untangle the web of my life path. Egypt is a place where more than half of the population is under the poverty line and far too many children labor at a young age. I come from a family of small landowners who worked as farmers. I am the first generation that was born in the city. I achieved a level of education that was unprecedented in the family and my degree opened paths otherwise impossible. It paved a career marked by emotional and intellectual labor and being spared manual jobs. With this came a certain prestige. How one earns income can imbue more social status than actual wealth. In contrast, my tense relationship with my family meant I couldn’t financially rely on them. Coming from a town outside Cairo created a sense of urgency and commitment toward providing for myself and finding work.

Here is what happens in medical transcription: A patient meets a doctor in the United States, and upon the end, the doctors record the patient’s information, symptoms, examinations conducted, and treatment plan on an audio file. These are sent to our company and each staff member receives their lot. I am not sure why voice recording replaced written reports, but I always assumed it had to do with saving time and increasing overall productivity. We sat in the so-called computer lab, a dreary neon-lit room that fits 15 people. We face the screen, turning our backs on each other. The written reports are eventually sent back to the US. The word outsourcing was new to me. A medical transcriptionist in the United States receives the same salary as six of us in Cairo. I imagine those whose jobs became obsolete because Third World labor is cheaper.

The company kept us on a leash in hopes of renewing our contracts beyond the training phase. Our productivity was assessed based on how fast and accurately we transcribed the recordings. We had to learn the art of touch typing, i.e., without looking at the keyboard. The number of how many words per hour were flaunted on a board to maintain the competition. My maximum word count was around 50-something per minute. To further save time, pausing and playing the audio files was done through a pedal. All our limbs were involved. The pedal reminded me of my grandmother who sat in front a sewing machine, using a similar pedal, an object that seemed out of time and place.

The accuracy in transcribing relied heavily on one’s command of English. Mine was pretty good. I had begun to learn at elementary school. Thanks to the legacy of British colonialism, which laid the idea of English as capital and prestige, medical education in Egypt is taught in English. But it was my addiction to American TV shows and pop music (for example Mariah Carey’s songs) that improved my fluency.

The difficulty level of the transcription gradually increased. The doctors spoke faster and used more medical jargon. Some spoke in an American accent; others had a heavy Indian or Chinese accent. The most notorious was Dr. Ottavia, an orthopedic whom everyone hoped would not get assigned her files. She spoke so fast one could hardly discern if she was speaking of knee pain, knee sprain, or knee strain.

After months, some of the symptoms described in the recordings started to appear among us. Our dread of Dr. Ottavia started to become real. Some started to develop carpal tunnel syndrome because of the extended hours of typing. Others had back and neck pain. My ankle started to hurt and give way due to the pedal use. One night, my right knee twisted as I crossed the street to go home. That was the end of my first job and a scene that opened this confessional text.

“You united the cross and the crescent,” the Cairo orthopedic proclaimed after mentioning my diagnosis: partial damage in both the anterior cruciate ligament and the right meniscus. It was a clichéd reference to the sectarian tension between Muslims and Christians in Egypt. He ordered complete rest for one month, with which I couldn’t comply because I had another job to go to. If I had been an athlete, he would have performed a surgical intervention, the only way to achieve full recovery according to the doctor. Since I had a sedentary lifestyle (for some reason he said this in English), I should integrate a physical therapy routine into my life. I hated the sound of the word sedentary. He advised against running in the future and prescribed medicines for the pain. I never intended to be a runner, but I love to go on long walks, especially when I travel. I would live with chronic pain that constantly affects my mobility.

After my injury, I went back to the company only once to collect my last salary. I didn’t have insurance and there was no compensation, although it was a work-related injury. It’s true that I wasn’t always a diligent patient. The pain sometimes gets too much. I would start physical therapy and drop out after a few sessions. I often couldn’t afford the costs. I learned to live with pain, or more accurately to live in pain.

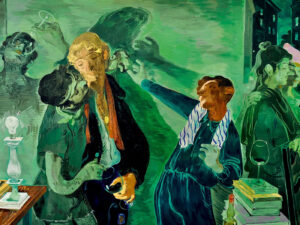

I sometimes wondered if the specter of global capitalism was a ghost who haunted us.

A direct consequence of the alienation of man from the product of his labor,

from his life activity and from his species-life, is that man is

alienated from other men. … man is alienated from his species-life means that

each man is alienated from others,

and that each of the others is likewise

alienated from human life.

—Karl Marx

Work teaches us about pain, about the things that our bodies and minds must endure in order to maintain a decent life. Some pains are more subtle than others. At one point in my first job, I was offered another position, as a pharmaceutical inspector at the Ministry of Health. It was commonly believed that one should not miss such an opportunity since, back then, the government offered permanent contracts. One could go on leave while pursuing more lucrative ventures, then eventually return to ensure a decent pension. I didn’t subscribe to this dated worldview but needed the money. I also needed to prove my worth and reassure my independence. This was attainable through more work.

I asked my supervisor at the company to be transferred to the evening shift. After leaving the office that day, I felt a pinch in my heart. I was going to miss my morning shift colleagues immensely. They were the first friends I had made in Cairo, and they felt like family. The closest relations were with women, and they seemed to like me as well. When I think about it now, I suppose one or two of them were interested in me romantically. Especially Nadine who often complained to me about her abusive husband and used to show photos on her mobile phone of herself without a headscarf.

Parting with my morning colleagues felt like another family separation. One of the earliest lessons from work was that professional ambition collides with human relations, and often must trump them. It was an introduction to a new kind of pain.

When I moved to the evening shift, I felt an increased sense of alienation. The shift was slightly shorter than the morning one. I was often tired and usually fell asleep on the long bus journey to the company. My social life became more limited. The company followed an American holiday schema; we would get days off during Western Christmas, one week before the Eastern one, and had to work during Muslim holidays, which were the most important days off to be with family and friends in Egypt.

There was also another group dynamic during the evening shift. Hatem, a tall man with a beard and glasses, and who was a psychiatrist by day and transcriber at night, assumed the role of a leader. I think people felt a sense of gravity in him because he seemed like an insightful person. I was wary of authority figures. I felt that what others saw in a leader didn’t exactly inspire me. When it was time to pray, Hatem would come and persuade me to join the group prayer. I never showed up. I, along with the only Christian colleague, stayed behind in the computer lab. My behavior made me an outsider.

Alienation is inscribed into the job of medical transcription itself. We were physicians, pharmacists, and dentists, whose training was to prepare us to care for the sick. Instead, we sat for long hours in front of screens, listening, typing, and pedaling. We listened to patient complaints and treatment plans without playing in any part of it. Karl Marx described this state of alienation that results from the division of labor. The labor becomes more and more specific and repetitive, with no connection to the outcome, only to generate profit for an elite they don’t know.

“What is your relationship to pain?” asked the osteopath whom I started seeing in Berlin. The question left me close to tears. I would describe him as a more holistic type of physical therapist. He didn’t see his role being limited to teaching physical exercises and performing various kinds of treatments. He wanted to address the beliefs that held me from healing. I spent a good deal of time thinking about his question. The answer was: I had known pain for most of my life, the pain of loss, the pain of not being able to express who I am, and the loneliness that comes with all of that. I also realized experiences of neglect can be a source of giving. Outpouring helps on others to fill the holes in our souls. It doesn’t surprise me that I wanted to have a job that has to do with health and well-being. My need to heal was projected upon others.

Perhaps I started to get comfortable with the pain. My conversation with the osteopath, reminded me that I should not let the past dictate my present. To let go of the past so I could let go of my body aches. Pain and trauma are inevitable. A large part of healing lies in revisiting the narratives of pain. In time, I was also able to redefine the narrative of what happened that night when I got injured:

It was my first job. It was midnight. I was crossing the street. In the middle of the first lane, I twisted my ankle. I heard something crack. I fell to the asphalt. Cars were speeding in my direction. I jumped onto the pavement on the other side. I survived an impending death.

I eventually found my path to several jobs that fulfilled my passion. I naturally gravitated toward helping and healing and professions. I preferred to work with people providing counseling to those who most needed it.

I still knew that estrangement was something to accompany me. At my workplace in Berlin, I was an outsider too. For someone like me, labor is entangled in complex layers of identity and human experience. If I try, would they understand? When my turn came to speak of my first job to my colleagues, I briefly explained medical transcription. I told everyone that the important thing I learned from it was to how to touch type.