Gezi Park has become a ghost. But a ghost, by its very nature, being neither alive nor dead, cannot easily disappear. The memory of modern Turkey is not only a memory of violence, but also a memory of protests across generations.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The Gezi Park protests began in Istanbul in June 2013 and over a period of three months, spread throughout the country like wildfire. What began as a demonstration for environmental justice quickly morphed into a nation-wide uprising against authoritarian rule. A decade later, this moment seems buried in the deep past, but for those who lived through it, the Gezi Park protests practically transformed life in Turkey forever. The aftermath of the events is so confusing that we can no longer simply look at chronology to understand the genesis here, yet a decade of contemporary art in Turkey since then either advanced the events, attempted to process them or articulated the reality that they created. This story of art is perhaps not reliable as historiography, but it can give some insights about a moment in time that defines where we are today.

January–May 2013: Remembering the Past

It was a time of true effervescence for Istanbul, when it felt dynamic and energetic, although still somewhat unfree, and pressure was growing. As someone who had been in the country for only a few months, it was hard for me to explain where the asphyxiation came from. At the opening of Envy, Enmity, Embarrassment at the old ARTER (since relocated to a white cube museum) on the pedestrian Istiklal Street, the crowds were huge, and the moment was both tense and exciting. Hale Tenger’s installation “I Know People Like This III,” (2013) formed a narrow walk-through labyrinth at the entrance, and the assembled lightboxes serving as walls displayed a terrifying but discreetly sanitized journey though scenarios of violence in the public space in Turkey, from the Istanbul pogroms against minorities in 1955 to the military coup in 1980, and the protests in Diyarbakır that took place shortly before the installation was completed.

Photographs were sourced from archives, newspapers, and journalists, and printed on see-through clinical X-ray films, giving them a halo of strangeness and distance. But the images were not distant at all. These monumental juxtapositions of political violence, present in everyday images, felt retrospectively as if they exposed a fragment of the archive of cruelty that would soon be unleashed. While the situation was still apparently normal in Istanbul, the Kurdish-dominated east of the country was restive, as always, and the hand of oppression was never absent. One night, a number of pedestrians congregated around a street musician in front of the window of the installation, listening to a song I can’t remember now, not paying much attention to the lightboxes glowing in the dark with the translucent images. But it was perhaps the images that were staring at them, in a latent stage, about to reawaken in the following months. By the time the events of Gezi Park took place, a few months later, the lightboxes were already gone, but the images of violence in the public space in Turkey have never ceased accumulating.

When Lebanese artist and historian Gregory Buchakjian visited Istanbul later in the spring, we met with Hale Tenger at a restaurant in Karaköy. He was familiar with Tenger’s videowork “Beirut” (2005-2007), which shows the windows of the St. Georges Hotel, in front of which Rafik Hariri was assassinated by a bomb in 2005. Harmoniously fluttering white curtains are contrasted with the haunting sounds of war, pointing us at a dramatic interruption. The conversation centered on the shared fates of both countries, between political assassinations, protests, and unsolved crimes. Buchakjian showed us his work-in-progress, a long series of photographs documenting the architectural heritage of Beirut, destroyed by reconstructions, demolition, and amnesia. At the time, he was expectedly mesmerized by the abandoned and dilapidated houses on Tarlabașı Boulevard in Istanbul, once upon a time occupied by Christians and Jews.

Buchakjian’s instinct was to immediately photograph their fading presence, and their status as a ghost, while wondering who their inhabitants might have been. He photographed the buildings for the unpublished series Ghost City (2013) at the last minute before their demolition. In the aftermath of Gezi Park, which started as a protest about public space, the built environment and dispossession, entire rows of these houses were demolished to make space for a failed real estate project that still stands there empty. This process resembled the reconstruction of downtown Beirut in the postwar era and that Buchakjian had documented in his work.

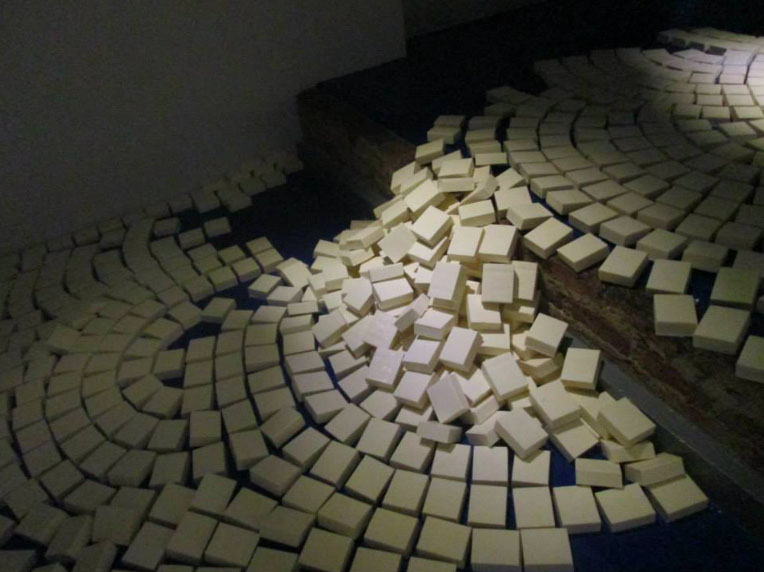

The dispossession in fact happened and has been happening continuously. A 15-minute walk from Tarlabașı, in the neighborhood of Pangaltı, a historical hammam of the same name was demolished in 1995 with the promise that it would be rebuilt, but a hotel rose in its stead. During that same spring, Greek-Armenian artist Hera Büyüktașçıyan, was concluding an investigation into the traces of the site, in the absence of any documents other than a tiny white and black photograph from the 1970s, as a part of a residency at PiST, a local art space that closed its doors in 2013.

Büyüktașçıyan, who was born in the neighborhood, home to the remnants of the Greek and Armenian communities, sought out a site-specific placement that would be both mental and physical: She reconstructed the imagined interior of the hammam entirely on bars of Turkish bath soap, with their characteristic citrus fragrance. This reconstruction, titled In Situ (2013), making reference to an archaeological artifact that has not been moved from its original place of deposition, was a psychogeography of a place that had become invisible, but that could still be conjured up through the imagination. On the opening night, I visited the exhibition alongside Hale Tenger and other members of the arts community. Little did Büyüktașçıyan imagine at the time that protests would engulf the city a week later. She recalled years afterward that a gesture of transformation of urban material into active memory, similar to In Situ, took place during the protests: local residents erected makeshift barricades around Gezi against police repression, using materials from the urban fabric itself, changing the meaning of spatial memory in the process.

Deniz Goran’s New Novel Contrasts Art and the Gezi Park Protests

June–September 2013: Gezi Park and the 13th Istanbul Biennial

We didn’t experience the beginning of the Gezi Park protests as anything like the news coverage imagined it. On the 28th of May, some 50 environmentalists gathered around the park to prevent its demolition and the construction of a planned shopping mall. The next day, a conference on the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze took place at Akbank Sanat, followed by a dinner on Kartal St., which was then a meeting point for the arts community, and a visit to the park with artists Seza Paker, Burak Arıkan, and art critic Ali Akay, where crowds were beginning to grow. The atmosphere was cheerful and that night ended at the upscale Reina nightclub (it sounds almost like a comedy, told from the perspective of today). By the next morning, the situation had escalated and the country had changed: The protest camp was raided by the authorities on that day, as protests spread like wildfire throughout the country. The following two weeks, the park would be occupied by protesters, until it was cordoned off by police on June 16th, even though protests continued throughout the summer.

The story is well-known; books have been written about it.

On May 30th, while escaping from the smoke of teargas raining on Taksim Square, I snapped a picture of a protester holding a banner that read “What if they demolish Central Park, Hyde Park, or Tiergarten to build a mall?” Although it might seem naive today, that was in fact the starting point — opposition to the destruction of public space. Many artists were active in the protests and the spirit of this moment continued to reverberate in Turkish art through the following decade. Soon enough, the themes and icons of Gezi Park (penguins, the woman in red, the protester fighting the police) became a subject for art. Most of these images have been forgotten today.

The 13th Istanbul Biennial, Mom, Am I Barbarian? — the title was borrowed from Turkish poet Lale Müldür — took place that year, curated by the late Fulya Erdemci. It was planned long before the events of Gezi Park and centered on notions such as a democratic public space and living together, and the idea of an agonistic public space borrowed from philosophers Hannah Arendt and Chantal Mouffe: the acceptance of permanent conflict and ongoing renegotiation as a potentially positive aspect of modern politics.

But as disturbances unfolded in the city, the biennial withdrew from public space and distributed its exhibits throughout art institutions in the city center. Erdemci’s reasoning was that it was problematic to stage a biennial in public while people were still fighting for their right to those very spaces. The controversy over the relationship of the biennial to Gezi obscured most of its content, despite the fact that it included works by major figures such as Gordon Matta-Clark, Hito Steyerl, and Thomas Hirschhorn.

Separated from the events by a decade, it becomes difficult to remember today moments in the biennial that served as catalysts of the present moment then, overwhelmed as we are by both journalistic images and the never-ending cycles of contemporary art, but two little known artworks were in fact unforgettable: Murat Akagündüz’s haunting five-screen video “Stream” (2013), consisted of reflections of the moon on the water of the five largest dams built upon the Euphrates River (Keban, Uzunçayır, Atatürk, Birecik and Karkamış). This subtle hypnotic work was quietly indicative of the destruction — ecological, archaeological, urban, social, hydric, that would take place all over the country in the following decade, from mining disasters to fire forests, poisoned bodies of water, the proposed Istanbul canal, and, most importantly, the flooding of the city of Hasankeyf and its archaeological sites in 2019.

The project “A Book of Songs and Places” (2013), by Lebanese artist Maxime Hourani, is virtually forgotten today; a series of workshops during which musicians led songwriting sessions for artists and social scientists, and looked at various geographic areas on the periphery of Istanbul, where urban development was transforming rural “wastelands,” and expanding the power of capital under the pretext of city planning. Hourani’s work reflected on how communities can conduct research on their own socio-political conditions, armed with non-traditional tools such as art, sound, and spatial surveys. It couldn’t have been more timely then, even though, as in the case of Akagündüz, it was grounded in long existing conditions.

Looking back at Gezi, I made a mistake when I told The Guardian then that the biennial wasn’t engaging with the protests and the public. Curator Fulya Erdemci corrected me in a short interview I conducted with her, shortly afterwards, when she soberly affirmed: “There’s no direct connection between the biennial and the events of Gezi. It’s too premature, we’re living through it, and I don’t want premature formulations. Art has the capacity to foresee, and before returning to Istanbul I knew we had to touch on the public democratic space, on politics, and on the burning urban transformation, but there was no specific attempt to make this connection. It’s too soon. Maybe in five or ten years.” But ten years elapsed, Erdemci passed away in 2022, and rapacious urban transformation continued unmolested.

April–September 2015: The Golden Era of SALT and the 14th Istanbul Biennial

The Gezi Park protests lasted for about three months in 2013, but the after effects lingered for much longer, and sporadic protests would happen occasionally. Right after the protests, SALT, one of Turkey’s major art institutions, experienced a golden age, holding major exhibitions for Gülsün Karamustafa, Christian Marclay, and Akram Zaatari, among others. In 2015, it presented the most poignant exhibitions about contemporary Turkey in recent memory.

A Century of Centuries, curated by November Paynter, explored the violent legacy of the “long century” of European colonialism from the 1860s to the present. In the exhibition, Didem Pekün’s video essay “Of Dice and Men” (2011-ongoing) was one of the first artworks to address the historical ruptures of 2013 as part of a larger story: from an anti-austerity demonstration in London in 2011 to raw footage from Gezi, the artist reflected on the possibility of co-existing with so much violence, moving back and forth in time. Pekün saw the protests not as an exceptional and isolated event, but as part of a global wave of movements reflecting the uncertainty of the present.

The exhibition happened to coincide with the 100th annual commemoration of the Armenian Genocide in Istanbul (now banned), something that echoed throughout the exhibition. For example, Büyüktașçıyan explored the history of the Siniosoğlu Apartment, where SALT is located, previously inhabited by Istanbul Greeks, and Dilek Winchester displayed blackboards with Ottoman dialects written in minority alphabets such as Armeno-Turkish or Karamanlidika, languages absent from the official literary history. On the day of the memorial, demonstrators marching in recognition of the centennial; passing in front of the building were closely followed by Turkish nationalists. Both groups were separated only by a thin police barrier. The nationalists’ threatening chants could be heard all the way to Taksim Square, where Hale Tenger’s sculpture “Wishing Tree,” (2015) commissioned by writer Nancy Kricorian and philanthropist Osman Kavala (in prison since October 2017), enabled passersby to tie strips of fabric in commemoration of the victims. The day ended uneventfully, but it felt as if the fabric of reality could easily wither. That night in Istanbul was intoxicating: protests, remembrance, street brawls, nightlife, all at once.

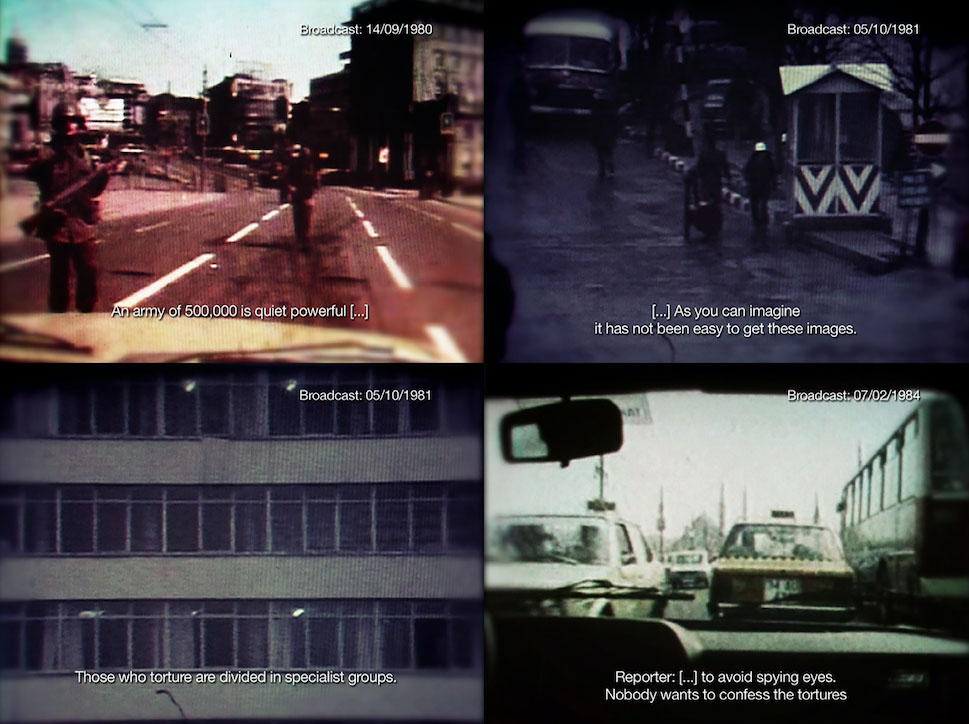

A few months later came the exhibition How Did We Get Here? which was meant to investigate the political background of contemporary Turkey, based on artworks and archival material such as popular magazines, banned books and TV shows. In the exhibition, Barıș Doğrusöz’s video installation “Heure de Paris: Separation” (2011) combined television footage from French and Turkish news during the 1980s, giving a truly disheartening impression of the media environment during a time when it was not permitted to film news in the country, and Turkey was presented with maps or through images obtained illegally, often filmed inside moving cars. The news items of 2015 shockingly resembled those of that earlier decade: martial law, pacification operations, and curfews in the Kurdish-dominated east. As the government’s grip on the media has grown increasingly tighter in recent years, we see the present projected backwards, and feel the uncanny continuity of violence and unrest in the country. Today, Turkey is one of the most unfree countries for journalists and has the most suppressed media in its history.

Another media broadcast appeared in the How Did We Get Here? exhibition: a recording of a football match in 1981, but one interrupted by the news of how many terrorists have been arrested, jailed, or killed. It’s part of Hale Tenger’s installation “The Closet” (1997-2015), a reconstruction of a work from 1997. Three rooms resemble a strangely shaped modernist apartment, with familiar smells of old, and a radio in the salon. The apartment is empty, plates are on the table, and one is left wondering what happened to the people living in this apartment, and whether they had to leave in a rush. In a conversation with the artist around that time, she revealed that reassembling the work didn’t feel too different from assembling it in 1997. She then circled back to the present: “How did we get here? Where? Where exactly did we get?” Although these two exhibitions captured so well the continuum between the present and the past exposed by Gezi, they also marked the end of this golden age in Turkish contemporary art. Soon after this exhibition, SALT Beyoğlu shut its doors. By the time the institution reopened two years later, the momentum for Turkish contemporary art that had begun in the 2000s had been partially lost.

A similar story can be told about the 14th Istanbul Biennial, Saltwater, held around the same time and curated by one of the most important living curators, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. Hers was a mega-biennial model: an enormous contemporary art show, covering the entire city and sprawling across dozens of locations, from the village of Rumelifeneri near the Black Sea to the Princes’ Islands, and including major artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Pierre Huyghe, and Theaster Gates. But it was so large and so ambitious that it couldn’t be properly digested in the urban chaos that is Istanbul. Some poetic moments were memorable, such as Haig Aivazian’s moving performance with the choir of the Holy Trinity Armenian Church at the Galata Greek School (very few people have memory of it), or Ed Atkins’ video “Hisser” (2015), which told the dramatic story of a man who fell down a sinkhole, exhibited in the crumbling Palazzo Rizzo on the island of Büyükada. The agonizing sound of the piece made the entire house shake, as if it were a metaphor for the entire country. It would be the last grand biennial.

December 2016-September 2019: Uncertain Times

The end of 2015 and most of 2016 was a period marked by more violence, including several major terror attacks, harsher censorship of the press, an unsuccessful coup, and even a military incursion into Syria. Protests had long died out, and after the state of emergency and heavy militarization, they were technically impossible. There was little encouragement to remain in the country, and a major exodus of members from the arts community began. In Istanbul at the end of 2016, I came across Bilge Friedlaender’s exhibition Words, Numbers, Lines (2016) at ARTER. The late Turkish-American artist is the only representative of minimalist abstraction in the Turkish canon, and her delicate works on paper, while created during the 1970s and 1980s, contained nothing of the heavy weight of the historically informed practices of the previous decade — her work was imbued with references to modern art, antiquity, and eco-feminism. But there was something disquieting about this beauty and fragility that timidly encapsulated the anxiety in the city.

It transmitted the eerie feeling that something could happen at any moment and suddenly disrupt the (already tense) order of the street. On the yellowing surfaces of neatly folded and crumpled paper, signs of striation would appear: On closer view, subtle lines on pencil or torn paper would become cracks, and enormous ruptures, atomization, chaos. Two days later, shortly after New Year’s eve, a mass shooting killed 39 people at the same Reina nightclub in Örtakoy where I had ended up on the first night of the Gezi Park protests on May 29th, 2013, and shuttered the club for good. The Islamic State claimed responsibility. A chapter closed, and an even darker page had turned.

2017 was a strange year: Not only did a referendum further solidify the harsh and reactionary response to the events of 2013, with the state of emergency continuing, but we also witnessed an artistic rebirth of a different kind. It was largely based on the art market, heavy in self-censorship and rich in cool abstraction. Another biennial took place, museums relocated into sleek modern spaces, and new galleries opened their doors. But it was another country.

When the Sharjah Biennial opened a chapter in Istanbul in 2017 at the Abud Efendi Mansion in Istanbul, Kurdish artist Pınar Ӧğrenci presented her video installation “Only Dead Fish Go With the Flow” (2017). It is an act of poetic bravado, consisting of a film projected on domestic objects and irregular surfaces, depicting the migration of pearl mullet fish from Lake Van to fresh waters every year in springtime. The metaphor is one of survival and adaptation, and it translates into the bitter realities of migration, displacement, and survival that have shaped Turkey. In 2015, Ӧğrenci, among other members of the peace initiative “Barıș İçin Yürüyorum” (I Am Walking for Peace), was arrested in Sur, one of the central districts of Diyarbakır, and released a number of days later. There began a series of trumped-up charges and court cases, which prompted Ӧğrenci to leave the country.

Right before the Covid-19 pandemic, a sense of normalization returned in which this new reality was accepted as unquestionably true and unchangeable. But an important voice of dissent from this period was Alper Turan and his curatorial projects on the histories of HIV in Turkey: first Positive Space (2018), at the American Hospital but also HIV Stories: Living Politics (2020), held at the Drama Queer collective, and in fact the last exhibition to open in Istanbul before the pandemic. The latter featured a touching video by Leman Sevda Daricioğlu, “Ziyaret” (2020), a visit to the grave of Murtaza Elgin, the first person diagnosed with HIV in Turkey in 1985.

Images of violence have accumulated in Turkey over the last decade since the Gezi Park protests, probably faster than at any other point in history.

The exhibition When the Present Is History (2019), a proposal by Greek curator Daphne Vitali at DEPO, explored the process in artistic practices through which the present suddenly becomes the past: how is it possible to say something meaningful about the present amidst so much uncertainty and turmoil? A number of artists in the exhibition worked with documents from the near present and attempted to reassemble them as if they were historical events, even though they are still ongoing. Banu Cennetoğlu’s “14.05.2019,” (2019) for example, gathered hundreds of local newspapers published in Turkey on a certain day chosen randomly, and collected them into several bound volumes, creating an archive of an undefined moment in the country, one for which a history hasn’t been written yet.

This archival fever isn’t simply a matter of record-keeping, but examines how information (and disinformation) is disseminated through the media, and the ways in which amidst so much disruption, a loss of memory happens almost immediately. Cennetoğlu’s bound newspapers reconnect here with Hale Tenger’s photographic archive, manifesting an underlying tension between historical documents and the present: when does a historical event end and the archive begin? Images of violence have accumulated in Turkey over the last decade since the Gezi Park protests, probably faster than at any other point in history.

The accumulation creates a paradox in the sense that it becomes difficult to read memory, not because there’s an absence of remembrance, but because we are overwhelmed by the sheer size of the archive and can no longer make sense of it. Amidst this confusion, the material that artists are working with is not so much the past as it is a state of latency, something being there, present, but not completely visible, or existing in a ghostly form.

Under certain conditions, these moments in time can become reactivated, but it can never be predicted when. This quality of latency applies to every historical process: cycles of violence, waves of protests, moments of liberation.

Epilogue:

Physical traces of Gezi Park are nearly nonexistent today: The park remains off limits to the public a decade later, and although no development took place on the site, intrigues at the level of municipal politics suggest that the park could still become the next target in a rhetoric of conquest, now a signature of the ruler’s sovereignty, expressed through the destruction or transformation of secular or republican symbols. The iconic images of Gezi have long disappeared from political imagery, and although the movement still holds certain emotional value for dissidents in Turkey, the mention of the events is a rare occurrence nowadays. Gezi Park has become a ghost. But a ghost, by its very nature, being neither alive nor dead, cannot easily disappear. The memory of modern Turkey is not only a memory of violence, but also a memory of protests across generations.

In 2019, sociologists Cihan Erdal and Derya Fırat wrote in a compelling and still untranslated essay (penned a year before Erdal himself faced political persecution), about the politics of ghosts in relation to protests movements and Gezi Park, making reference to an idea of Jacques Derrida, that ghosts today are not supernatural beings but simply the return and persistence of elements from the past. In their view, protests movements, even when their goals are defeated, do not die easily because every time they establish a new, radical imagination of time, disrupting the abstract present of capitalism, by means of quoting each other: different historical moments and social movements, such as Occupy, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the anti-Iraq war protests of 2003, the Jornadas de Protesta Nacional in Chile, or Gezi, speak to each other through symbols of earlier events.

These symbols carry traces of other struggles: when Taksim Square, one of the epicenters of the Gezi Park protests, was banned for workers in 1979, the symbols of the left factions were hung on Konak Square in the city of Izmir, a gesture that was repeated in 2013 on the facade of the Atatürk Cultural Center. The center was demolished in 2018, as part of a plan to demolish any physical memory of the Gezi Park movement, but these banners might yet reappear elsewhere, sooner or later, we can never know when. Artists in Turkey continue to articulate dissent not necessarily through these political symbols alone, but also through extended dialogues with the strategies of different generations of artists, who tackled similar historical moments, shedding light on our continuity with the past. The archive is not simply accumulation, but also interpretation.

In recent exhibitions, Kurdish artists have continued to engage in this transtemporal dialogue. The installation “Harvest of Time” (2023) by Fatoș Irwen, who spent three years in prison right before the pandemic, was shown at the Zilberman Gallery in Berlin, and nearly coincided with the February 6th earthquakes; the room is filled with earth and planted with cobs made out of hair, creating a human field for harvesting, where the fates of peoples and lands in her native Diyarbakır merge, not unlike the earthquake region. Ateș Alpar was only 20 years old during the events of Gezi, but the tragic story he tells through photography and video in his exhibition The Stone Shell is Silent (2023), at Merdiven Art Space, recalls the demands for environmental justice at Gezi Park: the intentional flooding of Hasankeyf and its archaeological sites dating back 12,000 years, in order to make space for the Ilısu Dam, is a chilling account of cultural and natural destruction intertwined with political and economic interests that reconnects with Akagündüz’s reflections of the moon on the water of the dams, a decade earlier.

According to Erdal and Fırat, “We think that memory should be reconstructed today and considered as a radical invitation to democratize the relationship between generations in political space.” In other words, the instability of remembrance triggered by the infinitely expanding archive of injustice, calls for artists to constantly rework, reorganize, and reassemble what remains from the past in the present, almost obsessively, in order to not lose sight of the present moment, before it quickly fades from view, and so that other generations can rework this archive once again, based on their knowledge of the future.

The ghost of Gezi Park contains no arrow of direction right now and is frozen somewhere in the past, but it also contains the knowledge, the possibility that it can thaw at any moment. In spite of the circumstances, the future remains nonetheless open.