The first steps away from wasta and Za’im are always difficult, if not impossible to take. A selfish loser walks away from wasta and the Za’im nefarious agenda he created and instrumentalized.

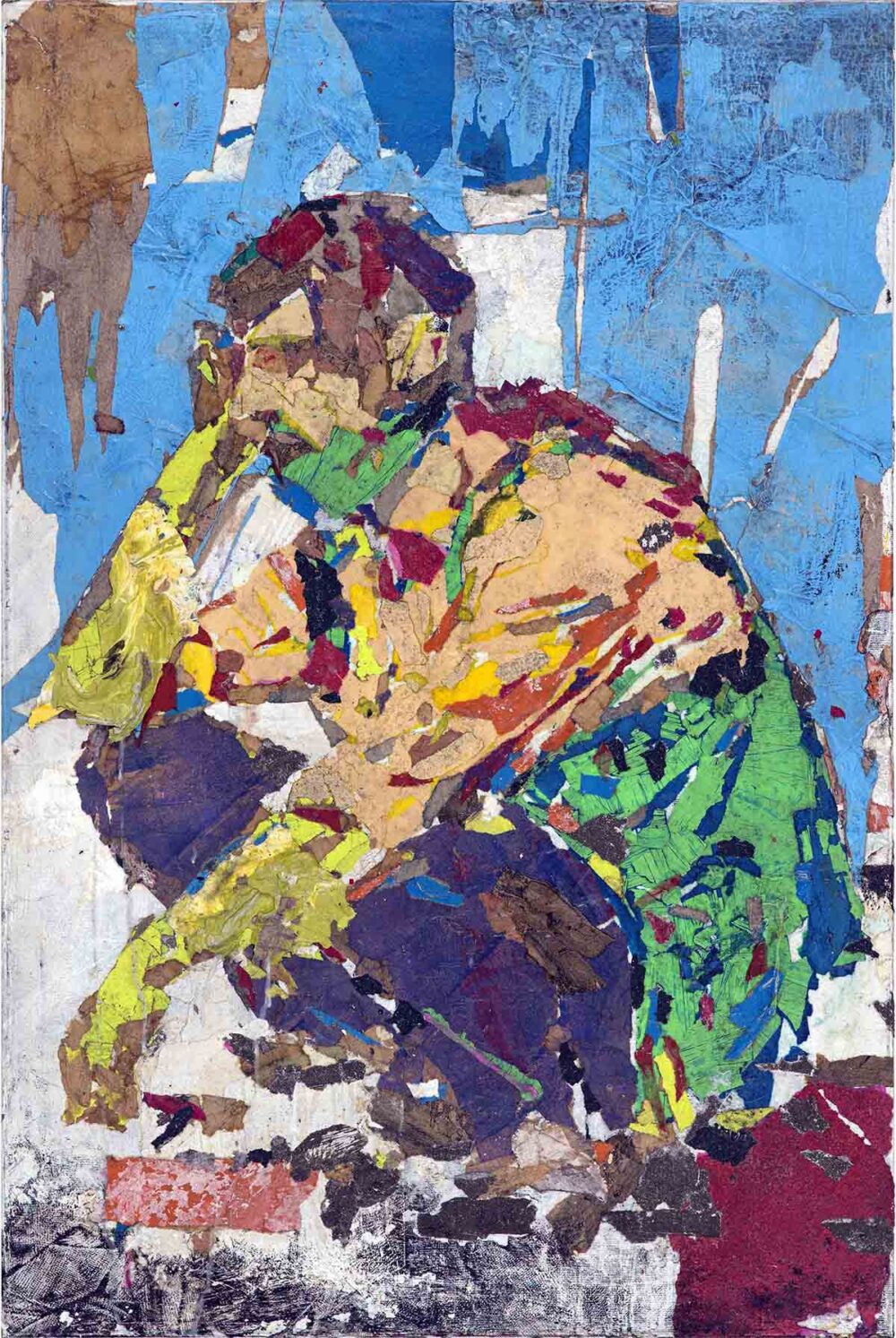

Youssef Manessa

You stand there, waiting, at the far end of the dock, in the midnight heat, just out of the view of the slack-jawed patrolman who’s been paid not to look your way. In between audible prayers meant to dispel suspicion, he rocks back and forth on his lame leg as if he’s expecting to be caught and needs to come up with a story on the spot, one plausible enough to get him out of the jail time his party might force him into if this looked too bad in the papers they don’t own.

Handheld through life, you’d think he would’ve had this rhythm down by now. But whenever he’s in a situation like this, he’s taken back to those moments, when his aging mother violently shook him with bloodshot eyes and whiskey breath whenever he embarrassed her with that lisp of his in front of the neighbors she didn’t like. These same neighbors who looked like him and talked like him, but who pushed him and kicked him in that dead field right over there that they would call a playground because they were strong and he was weak, and there was nothing better to do. That’s not to mention the father who was never there, the older brother who got in with the wrong crowd, and the little sister who liked boys just a little too early. Because it never stops, and it’ll never stop, going on and on like this for hours and hours until he’s inevitably caught.

But this time.

This very last time.

They told him there couldn’t be any more mistakes and that he had to figure something out.

Or else they would.

So, to calm his nerves, he pulls out the pre-rolled cannabis he stole from his son’s drawer, hoping he can pass it off as a cigarette if anyone took the time out of their day to talk to him. But, for some reason, you watch him burn his thumb for the second time, fidgeting with a lighter that he knew was faulty. You thought you would find it funny the first time, but you know it’s hard to laugh on an empty stomach that’s only been fed platitudes and false promises. It isn’t until the third time that you know that you’re not laughing, not because you’re about to collapse, but because, in spite of yourself, you feel sorry for him.

And now that you’re finally aware you’ve been glaring at him with your one good eye for longer than you’re willing to admit, you can’t help but wonder how either of you ended up where you are now and who you knew to end up that way.

You know you shouldn’t think like this. You know it won’t change anything. You know they’re right about it not changing anything. Because, of course, they’re right. They’re absolutely right.

But they’re wrong.

They’re wrong.

They’re absolutely wrong.

And for the first time in your miserable life, you realize something: This man needs this.

This wasta that you voted in, with pride, knowing what you were voting in, knowing who you were voting in, but never got yourself and then ranted about for years to whoever would lend you their ears.

And when you get this, when you finally get this, you’re not upset.

You’re not angry.

You’re done.

You’re just done … with this … with all of this …

Because at that moment, you also realize that this is a man who can only make it in a country like this. In a country where your future is your father’s past, and your father’s father’s past, and his father’s before him. In a country where your mothers only married them for the same reasons, your grandmothers gave birth to them. In a country where they’ll all have to be left behind, in one way or another, and you can pretend that’s not what you really want.

And after this precious, fleeting moment, you finally understand the one thing that all the platitudes and false promises never bothered to explain, that you being here tonight in the midnight heat, just out of the view of the slack-jawed patrolman, is just as much about him as it is about you.

Men like him are the reason and the only way a system like this is created.

But he doesn’t realize that. He never will. All his life, he’s been told things. Too many things. Things that made him feel at ease when it wasn’t warranted. Things that made him feel good when he didn’t deserve it.

But that doesn’t matter now because you’ve been told a lot of things, too.

You’ve been told that across this narrow sea, a land of opportunity awaits you. A land where you’re allowed to live the life that they wouldn’t let live here and that you sometimes wondered if you ever really wanted. A land where you can finally be the man you always said you were even though, in those rare instances when you’re honest with yourself, you know that can never be.

And you don’t know what this land looks like. And you don’t understand what it sounds like. And you can’t even pronounce its name. But you still stand there, waiting, in spite of your concerns, your very reasonable concerns, because what’s really waiting there behind you?

A future curtailed on the promise that the degree that was purchased for you from the university you never attended would open doors; a career of odd jobs and demeaning favors in exchange for the next odd job and demeaning favor; a community that has long since abandoned any pretext that the vision that your son fought for, that your son died for, just like your father did, was anything but an attempt to enrich whoever was signing those checks.

And now, you’re stuck, stuck in a way that the Za’im won’t pull you out of without it costing you more, but you have nothing more to give. All you have to go back to is a cramped apartment with stained walls and cracked floors where you live on top of your father, and your father’s father, and his father before him in the same room you grew up in, but that now houses your wife and daughters.

A wife and kids that you say you love, that you say you’d do anything for, that you said you did everything for, but you know, you’ve always known, it’s only a matter of time.

Because even though you said you were coming back, you aren’t.

You never were.

And that’s why when you finally get on that rusted ship that’s so slightly off-center as to make you worry about your chances, you take a deep breath and never look back.

*Coersion and bribery underpin the corrupt patronage in Lebanon, known as Zuama clientalism or the Za’im system.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)