In an interview with curator Nadine Khalil, we discover the artists on display in Dubai in the exhibition, I Can No Longer Produce the Limits of My Own Body, on view at the NIKA Gallery through the 24th of February, 2024.

Naima Morelli

In the middle of the gallery NIKA Project in Dubai space stands a series of objects encrusted in a red, blood-like substance. A chair, a pair of shoes, and behind it, several frames. On the wall, a video shows a woman breaking out from a big vase, like a little chick born out of an egg.

This is a work by Sara Niroobakhsh, an Iranian artist working with performance and installation, mostly around the theme of the feminine psyche. The broken vase exposing the half-naked body of the performer is a powerful image of shattered intimacy. And it is precisely the disappearance of an intimate dimension that is one of the central themes in the show “I Can No Longer Produce the Limits of My Own Body” at NIKA Projects Space in Dubai, curated by Nadine Khalil.

The evocative show’s title has been inspired by a quote by Jean Baudrillard, from his 1987 book The Ecstasy of Communication: “It is the end of interiority and intimacy, the overexposure and transparency of the world which traverses him without obstacle. He can no longer produce the limits of his own being, can no longer play nor stage himself, can no longer produce himself as a mirror.”

Khalil says her choice of works offer a subversive take on the French sociologist’s statement. “At a time of live-streamed genocide and mutilation in Palestine, I argue that the body is not singular but multiple, a fugitive form that is embedded within non-human and natural worlds,” says Khalil.

The Dubai show illustrates this concept by featuring seven artists — mostly female, mostly from the Arab world — working on the body in the era of technology. Liane Al Ghusain, Mirna Bamieh, Isaac Sullivan, Dalia Khalife, Sara Niroobakhsh, Lilia Ziamou, and Christiane Peschek are all artists who test the physical and conceptual limits of the body with their art.

Bodies in the Middle East

For Khalil, the show is coming full circle with her research around the body. She recalls her first encounter with feminist art as a 23-year-old student of anthropology. The soon-to-be curator found herself in a museum show for the first time in NYC, entitled Here is Elsewhere, curated by Mona Hatoum. She remembers her amazement at the time in observing how the expressions of women’s struggles elsewhere resonated with Hatoum’s own sensibility as a diasporic Palestinian artist.

“I still remember how it felt inside my body when apprehending art by Cindy Sherman and Kiki Smith dealing with sexuality and the body politic, and especially Ana Mendieta’s shape-shifting Facial Cosmetic Variations,” she says. “It was a moment that took me outside myself and enabled me to develop a spatial sensitivity around art and what it can do on a visceral level.”

But can these types of works tied to body politics be exhibited in the Middle East like they are in the Western world? According to writer and activist Shereen El Feki, author of the book Sex and the Citadel, the Arab world, while being very diverse, is characterized by three major taboo themes: politics, religion, and sex: “No matter where you are in the Arab region you are somewhere on this spectrum of the forbidden,” she writes. “Religious, secular, and political authorities have used sex as a tool of social control through the ages. Those in power have always sought to control female sexuality because it is central to reproduction,” the author explained in an interview when the book came out.

But precisely because of these boundaries and cultural norms, the body constitutes the perfect lens for examining the region’s complex social landscape. And art is the ideal medium to articulate reflections around the body.

Nadine Khalil notes that when it comes to approaching the body and body-centered narratives through art, what can be considered “radical” in the region is quite varied, from the more explicit and political (for example in the Levant) to far less so in the Gulf.

The curator engaged in conversations with all the artists in the show, taking the context into account. “More often than not we sought to push boundaries, to respond to them, always with openness and respect, rather than allying ourselves with any entrenched ideology,” says participating artist Lilia Ziamou.

The body’s transformations

A Greek and American interdisciplinary artist based in New York City, with a background in the areas of innovation, technology, and design, Ziamou has always been interested in the physio-biological and the transformative-digital.

“In my work, I’m intertwining the concrete and the imagined or imaginable, the stark evidence of an anatomy and the dynamics of technological layering,” she says. “I’m casting the body not as a sum of its limits but as an unbounded, multiple entity, freely ‘embodying’ its potentialities.”

Her work spans sculpture, installation, photography, digital paintings, and digital drawings. In the Dubai show she had a series of drawings called The Bone as Flesh, where delicate digital drawings play on ambiguity: is it tender flesh we are looking for? Or hard bones? Is it desire, or death that is evoked?

The artist seems to be asking: What is essential to the body? Does essence require that something remains unchanged through time, or can its components bend and morph as the body enters new contexts? “In my art practice, I use advanced technologies to re-contextualize what makes a body itself or not itself, or both itself and not itself, at once,” she explains.

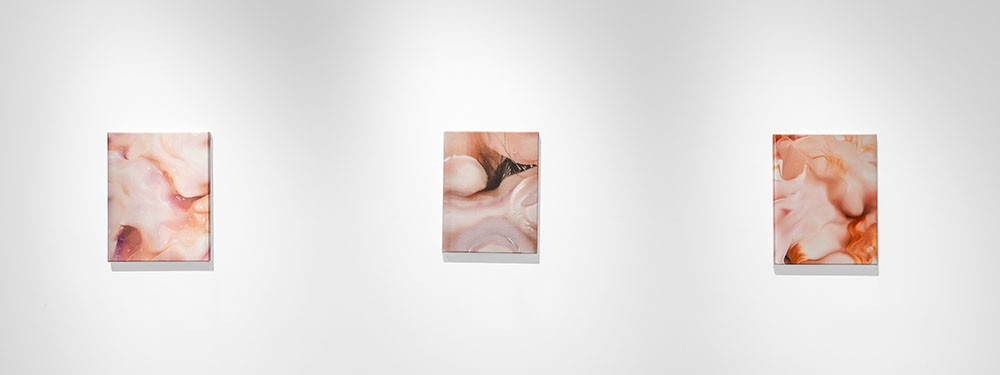

The modification of the body through modern technology is also central in the abstract images of Christiane Peschek, an artist in the show who deconstructs the concept of the White Male Western Man of Reason. Her images can be interpreted as amasses of flesh, or clouds, and investigate the meaning of intimacy when it comes to the interaction between humans and technology. Her process consists of retouching selfies by using filters and self-optimization tools. After being over-optimized excessively, by applying over 400 filters, the final image is vanished, blurred.

“I feel it’s crucial to be blurry and undefined in a society of hyperdefinition and over-exposure,” she says. “With my work, I’m observing the abyss and possibilities of an online intertwined lifestyle.”

Intimate stories for the Arab world

In her choice of artists, Nadine Khalil says that she was interested in works that embodied performativity in the region she is immersed in that is looking outwards. She admits that the show features predominantly women-centric perspectives, however the works in I Can No Longer Produce the Limits of My Own Body are not about the gendered body per se. According to her curatorial statement: “Rather, they take a post-human perspective of entanglement and fluidity and interrogate the notion of boundaries by creating unique and site-specific architectures of occupying space, whether this is building a kitchen for fermentation or creating the material manifestations of grief.”

In the former, Khalil is specifically alluding to an immersive work especially commissioned for the show, “Sour Things: The Kitchen” by Palestinian artist Mirna Bamieh with a sound composition made in collaboration with UAE-based artist Isaac Sullivan, called “Open Your Mouth,” in which he multiplies her texts and vocals to create a polyphonic subjectivity.

“Its components position fermentation to sharpen the senses, going in and out of verses, making the senses sharper, and the listening more attuned and applicable,” says the artist. “‘Sour Things’ references the multiplicity of meanings of the taste sensations produced by acids and characteristics of foods, such as ‘sour’ which can also be used to describe the expression on one’s face; the smell of one’s breath, or the feeling one has towards the undesired outcome of a particular situation.”

In this sense, the body is absent, and yet it expands into a kitchen: “The body becomes a stage of rawness, in which revealing and confessing is constructed overeating, devouring on one hand, preservation, transformation, and decay on the other,” continues Bamieh. “The excess will reveal its sourness if only one looks long enough.”

The political body

Khalil notes how today individual and collective bodies have become overexposed, mediated, and circulated via information networks.

A work that deals with this idea is by Palestinian-Kuwaiti artist Liane Al Ghusain, whose artistic research centers around the fields of mysticism, feminism, post-colonialism, and science fiction.

For the show, she created 29 stitched clay amulets for each of the Palestinian women imprisoned in illegal occupier prisons as of January 2023. “It is a response to the conditions of female political prisoners, who although less subjected to torture like male prisoners, are cuffed to hospital beds by their hands and feet while giving birth,” recounts the artist.

The amulets are made from pink stoneware and represent abstracted wombs. Carved on the insides of the wombs are a series of letters and numbers; they have been inserted with pieces of paper, to mimic ancient spell-binding rituals for protection from Palestine and surrounding regions. Each amulet contains one of the names of the prisoners and is bound with iron-oxide dyed and hand-knotted thread.

The intimate connection with ourselves

“I Can No Longer Produce the Limits of My Own Body” doesn’t give us easy answers, but rather elicits different — and difficult — questions: “With this show, I’m interrogating the limits of our emotional, technological, and environmental bodies,” says Khalil. “The artists seem to be asking: how can we find languages for the body, which in turn collaborates with AI, living bacteria, and movement?”

In her curatorial process, Khalil finds that the artworks and artists teach her, rather than the other way around: “I always start from the ground up, looking at artistic practices as the main source of research and theory,” she says. “In the show, you will find artists who comment on structures and collapse in Lebanon and Palestine, but there are also very personal stories about corporeality, care, exhaustion and how to grieve a mother.”

“I looked for works that performed and signified this quest for otherness inside ourselves, a sense of being-in-the-world that was entangled and hybrid,” she says. “I’m interested in a notion of embodiment that points to seepage between biocultural categories.”

In this sense, the performative work of Dalia Khalife gives us a last insight that summarizes the show. It is a performance set against the backdrop of her life-size digital avatar of herself, exploring sweat as a political and paradoxical condition. In her movements, the artist embodies the extremity of states of ecstasy, abjection, elation, and grief.

In these states of testing the boundaries and physical limits of our own body, we can perhaps reach a real knowing of our human substance, a key into intimacy. An intimacy, a closeness with ourselves.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)