Give to me the reed (nay) and sing thou!

Forget all the cures and ills.

Mankind is like verses written

Upon the surface of the rills.

—Gibran Khalil Gibran, The Procession

Reem Halasa

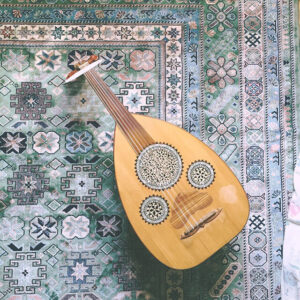

There’s a tune that calls to the heart, that speaks to the yearning and sorrow of the soul. It comes from the reed flute, or nay (also ney). In Arabic the word “Aneen,” or moaning, is often used to describe the mesmerizing nay-created tune that unites the human spirit with both nature and the divine.

The nay is among the oldest wind instruments known to civilization, and it is deeply woven into Middle Eastern popular culture and musical heritage. But with past colonial influences and contemporary Western cultural hegemony, our societies are losing their connection to this rich heritage, and traditions such as folk music are losing their hold and disappearing from our consciousness.

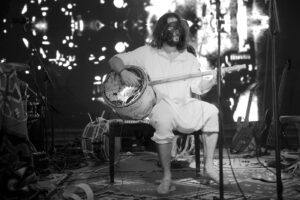

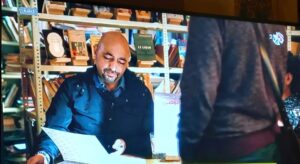

Rabee’ Zureikat is on a mission to restore severed links to the Arab past and revive our musical heritage for future generations. Fueled by his infatuation with the music of the nay, he wanted to learn to play this instrument, but his journey proved more arduous than it had to be.

In 2016, Zureikat embarked on a quest to acquire a nay. He searched everywhere in his native Jordan but came up empty-handed. At that time, Jordan had only a handful of nay players. Eventually, he ordered the instrument from Syria. Zureikat was perplexed but his quest didn’t end there. “I couldn’t believe that an instrument ingrained in our heritage and made of natural resources from our land was nowhere to be found.”

His ordeal ignited his drive to learn to handcraft the nay and not just learn how to play it. “Our ancestors used to make their own instruments, so surely we have the materials in our natural environment,” says Zureikat of his thinking at the time.

He knew that the hollow reed, which is used in crafting the nay, was historically native to the Jordan Valley. So, he went on a journey to find the right hollow reed to use in his craft. For months, he experimented with a variety of reeds in a small workshop in Amman. Through trial and error, he eventually mastered the art of making a finely tuned nay. Zureikat took his newfound passion across Jordan, sharing his skills with young people from different communities in hands-on workshops on how to fashion a nay from local resources, and teaching them the basics of playing their new instrument.

Through his work with marginalized communities, he noticed that children often miss out on the cultural and musical experiences to which their counterparts of higher economic status are accustomed. His workshops offered members of these communities a way to enrich their daily lives with music.

“I wanted to teach children how to craft their own nay with resources from their environment at the lowest costs,” says Zureikat. These raw materials can be hollow reed, or a more accessible plastic piping with the right diameter. Before concluding a workshop, he would leave the community simple tools to practice the craft.

Now his students are becoming the teachers; they continue his mission and teach others in their communities how to make and play the instrument. “New generations are learning our music heritage and the old songs their ancestors used to sing on different occasions,” Zureikat says.

In 2017, he co-founded Bait Al Nai (House of Nay) with fellow nay enthusiasts Laith Suleiman, Serene Huleileh, and Raed Asfour in Jabal Al-Weibdeh — one of Amman’s oldest neighborhoods and a well-known hub for arts and culture. Bait Al Nai quickly became a cultural fixture.

Zureikat and his colleagues are dedicated to bringing the public closer to the experience of nay music by teaching people how to play the instrument itself, and even how to craft it on their own. Bait Al Nai became the meeting point of people who are passionate about traditional music and the nay instrument, a place where they can enjoy musical evenings and collaborations with local and regional musicians.

With a modest workshop and a handful of tools, Bait Al Nai produces finely handcrafted reed flutes, and these instruments are bringing joy to people around the world.

The nay is dubbed the “mother of all wind instruments,” as it goes back at least 4,500 years. In the Great Pyramids of Giza, there are depictions of musicians playing the nay, as it was an important instrument used in religious ceremonies and social celebrations. Excavations in the ancient Sumerian city of Ur (southern Iraq) have revealed curious-looking flutes made of bones of large birds.

In Sufi tradition, the nay is an important instrument. It is said that it speaks to humankind’s love for and longing to be with God, and its soulful tune often accompanies lamentations about being separated from the divine. The nay is mentioned in Sufi literature and poetry; a great example is “Masnavi” by the Sufi master Jalaluddin Rumi; “Masnavi” opens with the words “Bişnev ez ney,” Persian for “listen to the nay.” The major theme of the poem is separation from a place or from the divine. “Listen to the nay, how it complains and tells the tales of separation pains.”

In more recent Levantine literature, the nay is mentioned in popular poetry, such as in Gibran Khalil Gibran’s book The Procession, with a repeating stanza beginning with “Give to me the nay and sing.” The poem became popular when the Lebanese singer Fairouz sang it in the 1970s, and it has ingrained itself in the minds of generations.

Music is influenced by the natural environment and cultural identity of the people, and the traditional nay played a major role in popular Arabic music; great musicians used it at times for an introductory tune to their ballads, one that would create a soulful experience.

Among the modern nay masters beyond Jordan are Turkish world music star Omar Faruk Tekbilek, Lebanese maestro Ali Jihad Racy, and Iran’s revered Mohammad Musavi.

The humble nay was always the instrument of the common man, a storytelling tool of tales of strife, loneliness, love, betrayal, remorse, and separation. It has been used by farmers in the fields, shepherds in the pastures, and folk musicians performing at communal celebrations.

Zureikat believes music is meant to be celebratory, an instinctive expression that transcends rules and music sheets. “The beauty of folk music is that it is inclusive; it brings the community together and anyone can participate and express themselves without judgment,” he says.

Bait Al Nai seeks to revive the lost art of handcrafting musical instruments and grew out of an initiative Zureikat started in 2007 called Zikra for Popular Learning, which aims to bridge the gap between urban and rural communities, and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and skills such as building basic homes using traditional practices, food preservation, and crafting tools, toys, utensils and even musical instruments using available resources and recycled materials.

Zikra (memory in Arabic) initiative ran with the slogan “we exchange to change” and it is based on promoting equity between rural and urban communities through cultural exchange, and aims to challenge the traditional perception of charity, where one party becomes the hero for saving victims of poverty, which is often demeaning to the poor communities, as Zureikat witnessed in his own charity work. He believes that these communities though poor have something to offer and share from their own lives, and that’s where the philosophy behind the initiative started.

To learn more about Bait Al Nai’s work, visit @Bait_Al_Nay and@Zikra_for_popular_learning on Instagram.