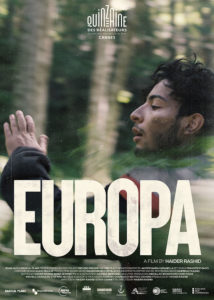

A son of Hama — a former prisoner and now a TV correspondent — takes his first steps towards his country in over a decade.

3:30 a.m. I haven’t slept in three days. I work as a main broadcaster on Arab TV, and I’m Syrian. A Syrian journalist means a constant headache. My country has been in the news headlines for 13 years. It swings between the first and last headlines according to the world’s fickle mood but it rarely leaves the bulletins.

My body is half-numb and my eyes are salty. Lack of sleep and many tears. I announced the liberation of Homs live hours ago. Two days before that I’d admitted I work for the liberation of my city Hama on air. Al Araby TV where I work is the only Arab broadcaster that has and still does support revolutions and democratic change without reservation in the Middle East.

I am the son of Hama. I say it now in a louder voice. I never before dared to do so in front of so many strangers. I was born in a city that Hafez al-Assad stigmatized after the massacre he carried out there in 1982, which the Syrians call “the events.” It is a mysterious, ambiguous description that protected them from arrest by the security services, men who also liked the name and adopted it. Hama events.

I had chosen to be a journalist against the objections of my family. My father was a simple government employee and my mother an elementary school teacher from whom I inherited a love literature and a quick temper. My father was very sad when I picked journalism. “You’ll end up as a teacher of national education,” he told me, and then stressed, “We are cursed and the security services won’t allow you to work in the state’s press institutions.”

“National Education” is not the title of a philosophy book, but rather the name of the mandatory curriculum for elementary school students that lasts until the end of university. Students learn the goals and teachings of the Baath Party; they memorize by heart the speeches of the president father. Ask any Syrian from my generation about “the meaning of the martyr in the thought of the leader,” and they will recall Hafez al-Assad’s speech on Martyrs’ Day without difficulty.

The clock strikes four in the morning.

The news is coming in fast. It seems that something is happening in Damascus. We haven’t heard a single statement from Bashar al-Assad since the military operation began a few days ago. This silence is strange, but not unusual.

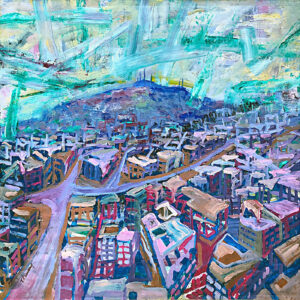

In my new apartment room, where I just moved, chaos is overwhelming. Only TV has found its way to a less crowded corner. The laptop is open on international TV screens. Twenty news alerts on WhatsApp ring together and then fall silent like an organized musical choir. I flip between the news. I send it by phone to my colleagues in the newsroom that never rests, to broadcast quickly. Everyone there is racing against time. As events accelerate, each second is pregnant with the latest developments. But so far no one knows exactly what’s happening. The armed opposition forces are rushing in without stopping, from the south and north of Damascus. Army units have withdrawn from Homs, but no one knows from which direction. Regular Syrian Army soldiers leave their clothes in the streets and flee. The checkpoints that spread like smallpox around Damascus were quickly evacuated, but the city center is calm. Silence reigns.

Anyone who reads the signs from afar knows that the regime is over, but none of us dares to think this. Disappointments have trained Syrians well over the past 13 years. We knew that the people of Damascus — I mean the civilians — had prepared themselves for the battle. They had whatever scarce, expensive food they could find and sat in the darkness of their homes waiting for ground zero. Many thought it would be the “Battle of Damascus.” Everyone expected the moment when the Russian Air Force would enter the fray and tip the balance of power in favor of Assad, as happened in 2016, especially after the statements of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, whom the Syrians hate.

An hour before I had spoken with my friend Malu, who asked me to write an article for The Markaz Review. I suggested several angles, and she said she had to have the article by Wednesday. I told her that a lot would change by then. I wanted to wait. She didn’t doubt that everything was in flux but she was insistent about the deadline, as is her usual strict habit. I had worked with Malu in 2014 on the anthology, Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, published in English and Arabic. I mention it here not to promote it — it’s out of date— but because of an incident that took place a couple of years after the book’s publication. A British woman returning from her vacation was detained at the airport. She had been reading Syria Speaks on the plane. The border police questioned her under the terrorism act. She was just a nurse with an interest in the Syrian revolution. At that time Syria was an accusation repeated everywhere. And Syrians in Europe had become half an insult and half a burden at best.

By a quarter past four in the morning, I no longer had any doubts. We received darkened images of soldiers withdrawing from one of the checkpoints in the center of Damascus, or from “Security Square” as it is known. I excitedly told my newsroom colleagues via the TV station’s WhatsApp group: “Guys, the regime has fallen.” I had only those few images, my intuition, and a hope that had been extinguished for years. I was immediately summoned to the station. I was driving like a madman. The night was gray. The sun was making its way lazily toward the horizon. I forgot to fasten my seatbelt. I was on tenterhooks. I was afraid I would die. For the first time in my life I was afraid I would die. My heart was beating like a plow in a dry field. I only had 15 minutes before I was in the studio ready to announce the news of Bashar al-Assad’s fall when it was confirmed. I reminded myself: I’m a journalist and I must hold myself together.

For the first time I felt that my choice to work in journalism was the right one. I wish my father were alive to see me. When he felt proud, he smiled and usually stroked his silver hair. More than once I had watched him do this as though he thought someone was filming him, and he was styling himself in front of an imaginary camera. His hair had never been this white before. My mother told me about that night in 1982 when my father had seen death with his own eyes. He had been lined up with his brothers and elderly father in the street in front of their house. They were awaiting the field execution order the regime had issued against all the city’s young men. But fate intervened. An officer recognized my father; they had been colleagues from university. He knew my father had no connection to the Muslim Brotherhood, which had rebelled in the city against Assad, the father. But Assad had made the mission of his loyal army easy and accused the city’s entire male population of working for the Brotherhood, and sentenced them to death. That officer interceded but only for my father and grandfather.

My grandfather was a traditional Hama man, very strong and proud — a firm, direct sheep trader. Without hesitation he told the officer that he would rather die with the rest of his sons if they had to be killed. That night was tense, as my grandfather admitted to me years later. The officer was tired. He sent everyone home and left. That morning when my mother woke up, laughing heartily as she told me the story, she found a strange man sleeping next to her. Rape had been the most effective security weapon during the days of the massacre, and she thought my father was one of the soldiers. I remember her saying, her black eyes shining, “His hair was as white as flour.” The intensity of fear had grayed him overnight. Then my mother corrected herself, adding with a conspiratorial wink, “But it became more beautiful.”

I arrived at the newsroom, out of breath. Denial, doubt, and hesitation in this profession tame emotions. I followed a team of journalists into a quick editorial meeting on how to announce major news in light of conflicting developments. In an interview on British television an analyst close to the Assad regime was saying from London that everything was under the control of the security services and army. What was happening was: “a redeployment of armed forces to protect sensitive areas in the capital in preparation for Russian air intervention, and that Assad was definitely directing the operation.” His confidence was unwavering.

I was reading the red at the bottom of the TV screens, getting ready to go on air to broadcast breaking news as per usual. Once my name had been breaking news on TV in Damascus after I had been arrested in the first demonstration against the regime witnessed in the capital city, in 2011. This was the most costly news of my life. When my father read my name on the red ribbon, images of thousands of bodies buried in the massacre and thousands of detainees who disappeared in prison flooded his mind at once. He knew the brutality of this regime. He saw my name as an arrestee and immediately had a heart attack. His kidneys failed. For months afterwards that he kept changing his blood and collapsing like a desiccated tree, as my brother told me.

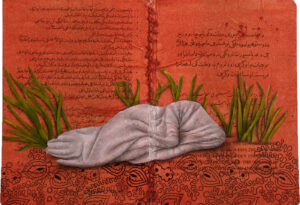

I was released after a bitter detention in the Air Force Intelligence branch prison in Damascus. The day, sunny and hot, stunned me. I remember standing and peering down at my trembling hands in front of a huge iron door with the Syrian flag painted on it. I did not dare look back to see where I’d come from. A passing car almost hit me as I crossed the street; it was as if I was sleepwalking. The effects of the torture were deep and severe on my soul. Hours later my father and I spoke on the phone. We didn’t say much; we only dared to cry. His deep, very sad voice sounded weak and exhausted. When I think of him now I feel a choking pain. That was my last memory of my father alive. His voice broke like an ear of corn with a dry stalk. He died hours later before I was able to reach him. I buried him and left Hama a few weeks later for London.

“This is the hour, viewers, five in the morning, Damascus time. The Syrian army officially informs its officers of the fall of the regime and news is: Bashar al-Assad has fled Damascus.”

I pinched myself as I read the news live. It must have been a dream. I must have been hallucinating. It must have been from the dizziness of sleeplessness and exhaustion. I replay the news perhaps twenty times to remind myself that it is real. I try to hold myself together in front of the camera. “Did you hear it, father, or do you want me to repeat it?” I keep saying to myself.

Prison left me with a deep fear that has remained a constant companion all this long while. It made me lose my father and deprived me of my country. The list of pain is long, and here I am announcing the news of the fall of the Assad regime. I write these words on a plane to Damascus for the first time in 12 years. Much water has flowed under the bridge, as they say. I hold no grudges and no desire for revenge. My soul is light like millions of Syrians now. I have only one or two wishes before I turn the page on the past forever: to visit my father’s grave and wash its white marble again; and to see my solitary confinement cell for the last time, where the doors of the prisons that have been opened will never be closed on anyone ever again.