A list of must-read Iraqi fiction.

In 2014, on the eve of the announcement of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, the shortlisted authors were invited to a panel discussion at NYU in Abu Dhabi. Iraqi authors Inaam Kachachi and Ahmed Saadawi were both shortlisted that year. It would be a few hours later that the judges would crown Saadawi, as that year’s winner for his sensational novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, chosen according to the selection committee for its “various levels of well-written, multifaceted narrative. For this and many other reasons, it constitutes an important contribution to contemporary Arab novelistic writing.” The novel was translated into English, French, Persian, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, and Bosnian.

During their conversation, Kachachi, author of the 2014-shortlisted title The Dispersal (Tashari in the Arabic title), commented on the changing state of Iraqi fiction specifically post-2003. Her commentary has marked the manner in which Iraqi literary works have come to be viewed.

“In Iraq, novel writing changed dramatically after the American invasion in 2003. Before that, many novels were published by the Ministry of Culture and Information, under the banner of war novels in reference to the Iraq-Iran war as well as the invasion of Kuwait. What is obvious is that during that time period, the politicians were the ones commandeering literary output, by forcing writers to produce inflammatory novels meant to inspire Iraqis to be brave, and to endure the hardships of war and to accept martyrdom in war as a natural consequence to vanquishing state enemies. After 2003, there was an immense surge in literary output by the old and new writers with ninety percent of these novels themed around the same wars but from different perspectives that relayed the pain of suffering, fear, and helplessness wrought from years of meaningless fighting. In essence what is being published now are novels of bitterness and grief. What novelists, such as myself, try to do now is tell our own experience, our own story under the cruelty of the past regime, in order to restore and reclaim the narrative from the distorted state it was reduced to.”

And so, here are 10 books that will help further explore the diversity of Iraqi literature available in English right now.

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, translated by Jonathan Wright (Penguin Random House, 2018)

Winner of the 2014 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, France’s Grand Prize for Fantasy, and The Kitschies’ Golden Tentacle Award for Best Debut.

Saadawi’s tale, reminiscent of Shelley’s 1818 monster, continues to win recognition and acclaim for its unique dystopian theme of a Baghdad mired in unimaginable violence, black magic and a city filled with only ghosts and ghouls.

Set in Baghdad in 2005, scavenger Hadi, resident of one of the city’s ramshackle neighborhoods, spends his time collecting the remains of the bodies of victims of terrorist bombings during the winter of 2005 and stitches them together to produce a corpse that he names whatsitsname. His goal, he claims, is for the government to recognize the parts as people and to give them proper burial.

When the monster comes to life, it sets out on a rampage of revenge killings targeting the criminals who he believes responsible for the murder of the body parts that make him up. “Who among us is not part evil?” he rationalizes.

As Hadi narrates his fanstastical story to residents of the local coffee house, every one believes it as nothing but an exciting feat of Hadi’s imagination. Except one. Ameed Surour Majeed, an undercover agent, assigned to track down the monster and bring it to justice.

The Dispersal (Tashari) by Inaam Kachachi, translated by Inam Jaber (Interlinks Books, 2022)

Shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014, The Dispersal is a timely and insightful novel about displacement, loss, poetry, war, and migration from a leading Arab voice. Kachachi’s latest novel follows the career of medical doctor, Wardiyah Iskander, a physician working in the Iraq countryside in the 1950s up to when as an old woman, she is forced to leave Iraq to join her family in France.

The Dispersal examines the experiences of two generations among the Iraqi diaspora in France: those who migrated as adults and those who were born and/or raised in France as it plays on issues of identity, home and politics of belonging with regard to generational and temporal aspects as well as highlighting all that is lost when the homeland is torn apart by violence and war.

An Iraqi in Paris by Samuel Shimon, translated by Piers Amodia and Christina Phillips with the author (Banipal Publishing)

An autobiographical novel written by the recently defunct Banipal magazine editor — who has been called “a relentless raconteur,” “a modern Odysseus” and “the Iraqi Don Quixote” — an Iraqi in Paris tells the story of an Assyrian boy, from Al-Habbaniyah, west of Baghdad, who dreams of becoming a Hollywood filmmaker after his hero John Ford. Frustrated at twenty in a country ruled by Saddam Hussain, Shimon decides to leave Iraq in 1979 to the US. However, following a harrowing path that saw him tortured in Syria, maltreated in Jordan, and nearly executed in Lebanon, he lands up as a destitute refugee on the streets of Paris in 1985 with nothing but his wit, humor and amorous adventures as he moves between bars, metros and friends. A cinema buff, he’s always dreamt of writing a script about his deaf-mute father with Robert de Niro to play the lead. What his readers end up with instead is a captivating tale of a childhood spent in a wretched hometown.

“An autobiography full of humor, irony, noblesse and sadness,” wrote Alaa Al Aswany, author of The Yacoubian Building. “It reminds me of George Orwell’s great book Down and Out in Paris and London.”

Baghdad Noir, edited by Samuel Shimon (Akachic Books)

Part of Akachic Books’ award-winning series of original noir anthologies, launched in 2004, one of the world’s most war-torn cities is portrayed through a noir lens in this chilling Iraqi crime fiction collection. Each of the 14 stories — many translated from the Arabic, others written in English and only ten of which are written by Iraqi authors — take place in and around Baghdad. A detailed map inserted at the beginning of the book is a great help to readers unfamiliar with the city. The introduction, written by Samuel Shimon, offers concise background information on the history of Iraq. The collection offers a Baghdad of diverse experiences and perspectives.

“While all Iraqis will readily agree that their life has always been noir, the majority of the stories in Baghdad Noir are set in the years following the American invasion of 2003,” writes Samuel Shimon. “In April 2003, the US invasion, though it precipitated the end of Saddam’s dictatorial rule, killed off any possibility of a secular, modern Iraq once and for all.”

The President’s Gardens by Muhsin Al-Ramli, translated by Luke Leafgren (MacLehose Press, 2017)

Set during the last fifty years of Iraqi history, this novel begins with a horrific morning. It is the third day of Ramadan and the village without bananas wakes up to find nine banana crates stacked by the bus stop, each with the severed head of one of its sons. One of them belonged to one of the most wanted men in Iraq, known to his friends as Ibrahim the Fated. The novel explores what it is that warrants such a gruesome ending. Described by Hassan Blasim, Iraqi author of The Iraqi Christ as “a contemporary tragedy of epic proportions,” the novel is masterfully woven from the miserable stories of the real people of Iraq, while highlighting resounding and universal concerns. Think One Hundred Years of Solitude meets The Kite Runner.

When the novel appeared in English in 2017, it was acclaimed by all critics and went on to win the 2018 Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation. The translation of its sequel, Daughter of the Tigris (2019) was practically published at the same time as publication of the Arabic.

The Book of Collateral Damage by Sinan Antoon, translated by Jonathan Wright (Yale University Press, 2020)

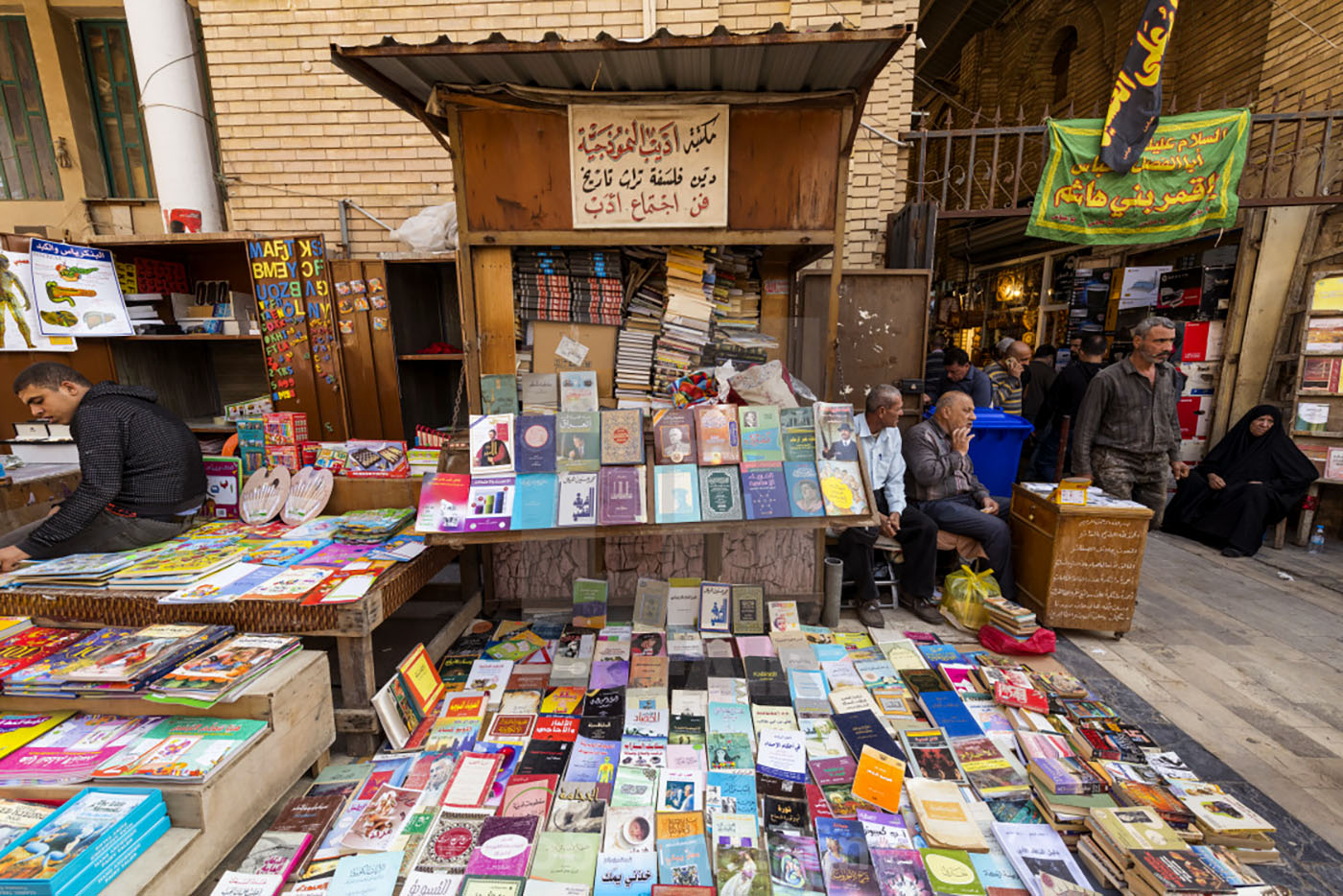

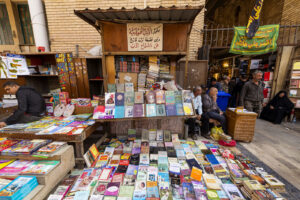

Widely acclaimed, Iraqi Sinan Antoon’s fourth novel, The Book of Collateral Damage, centers around the subject of the Second Gulf War to show how ordinary lives are rocked, shaped or ruined by conflict. The novel, considered Antoon’s most sophisticated to date, follows Nameer, a young Iraqi scholar earning his doctorate at Harvard, who is hired by filmmakers to help document the devastation of the 2003 invasion. Nameer meets Wadood, an eccentric bookseller on al-Mutanabbi street in Baghdad who is trying to catalogue “the things that are never mentioned or seen” that the war destroys in its path, from objects, buildings, books and manuscripts, flora and fauna, to humans.

Once in New York, Nameer is obsessed with Wadood’s project and finds that life in this city is movingly intertwined with fragments of memory from his homeland’s past and present tragedies that he is forced to examine within himself.

In his review of the book for The National (UAE), Malcolm Forbes wrote that Antoon’s “more fantastical elements put us in mind of the fictions of Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges. Not only is the novel prefaced by two epigraphs from Borges, but Wadood’s “open-ended book” is redolent of the “indefinite and perhaps infinite” universe in Borges’s short story ‘The Library of Babel.’”

The Baghdad Clock by Shahad Al-Rawi, translated by Luke Leafgren (Oneworld, 2019)

In 2018, Shahad Al-Rawi was the youngest woman author to be nominated for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. In the same year she went on to win the First Book Award at the Edinburgh International Book Festival.

The novel, a bestseller in Iraq and the UAE, takes us back to the 1991 Gulf War to follow the friendship of two girls, who meet in an air raid shelter. As the bombs continue to fall day after day and friends begin to flee the country, the girls must face the fact that their lives will never be the same again.

An endearing, yet grim, coming-of-age story in which the characters survive every hurdle through love and friendship, with an element of the whimsical and fantastical mixed in to good effect. The result is a bittersweet tale of shattered innocence despite the resilience of childhood.

The Watermelon Boys by Ruqayya Izzidien (Hoopoe Fiction, 2018)

Iraqi-Welsh writer Ruqayya Izzidien, who is currently based in Morocco, crafts an intelligent re-telling of the general political climate in the Middle East during WWI in her debut novel The Watermelon Boys. The novel sheds light on the role the local inhabitants of the Middle East, in this case the Baghdadis, played in securing English victory in Mesopotamia, overthrowing Ottoman rule and subsequently rebelling against the illegal shaping of their borders by foreign countries — a fierce and much neglected discussion regarding the aftermath of WWI that resulted in the deaths of many of the region’s civilians.

Hungry for independence from Ottoman rule, Ahmad leaves his peaceful family life on the banks of the Tigris to join the British-led revolt. Thousands of miles away, Welsh teenager Carwyn reluctantly enlists and is sent, via Gallipoli and Egypt, to the Mesopotamia campaign. Carwyn’s and Ahmad’s paths cross, and their fates are bound together. Both are forever changed, not only by their experience of war, but also by the parallel discrimination and betrayal they face.

According to the author’s note at the end of the book, the novel is based on real events from social aspects, such as food, dress, games and the two schools mentioned in the story, as well as documented political events. Description of the aerial bombardment was actually written by a Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot. The uniting of Shia and Sunni is also accurate. The anti-Jewish persecution taking place in the novel is based on an oral retelling by the author’s grandfather who concealed his Jewish neighbors during the wave of persecution in 1920 — an event, the author writes, that goes unmentioned in official historical sources, but which affected a number of families.

Iraq + 100: Stories from a century after the invasion edited by Hassan Blasim (Comma Press)

This is the first anthology of science fiction to emerge from Iraq. The stories re-imagine Iraq in 2103 — a century after an American invasion. Edited by Hassan Blasim whom The Guardian described as “perhaps the greatest writer of Arabic fiction alive,” this anthology contains stories that are heartbreakingly surreal, and yet utterly recognizable to the human experience.

When All Else Fails by Rayyan Al-Shawaf (Interlink Books, 2019)

A darkly humorous novel set in post-9/11 America and the Middle East in which Iraqi college student, Hunayn, navigates the US in the aftermath of 9/11. Although Chaldean, which means he’s not Muslim, Hunayn’s identity is constantly under question. Born in Iraq, and raised in Abu Dhabi, Rome and Lebanon, Hunayn is no stranger to being “the other,” and although he finds nothing in common with either Lebanese or American Christians, he refuses to play the trump card against those who pit “the others” against each other.

Having had his fill of disconcertingly upsetting and often violent episodes, he decides to go back to Lebanon where he thinks he’ll be better able to manage his life. Unbeknownst to Hunayn is that Lebanon is undergoing its own political upheaval. Mired in the midst of the country’s internal conflicts and those with its neighbors, Israel and Syria, Hunayn has enough on his plate when he is obliged to watch from afar as Iraq, “his fabled homeland and the owner of his heart,” unravels in the wake of the US-led invasion.

ممتن للنشر الجميل

Estoy tan emocionada de leer este. ¡¡Es maravilloso!!

Pingback: How did May Muzaffar's memoirs retrace more than fifty years of Iraq's cultural history? - Bitlis Haber