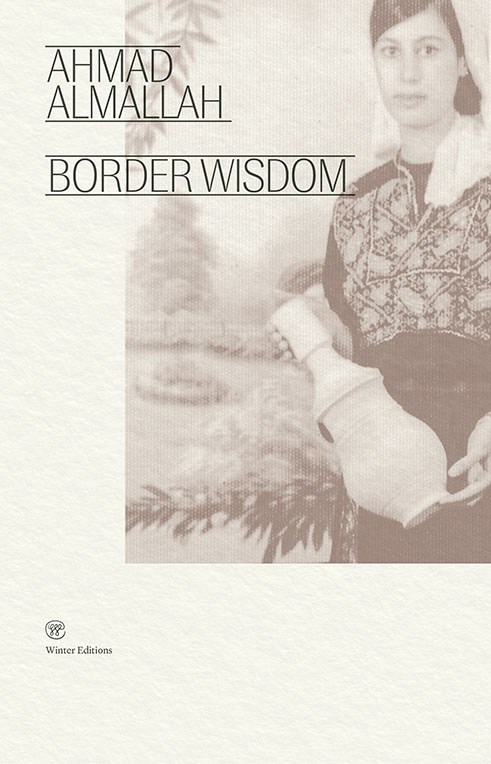

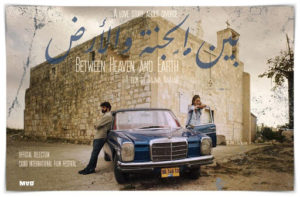

Note to the Reader: I wrote this letter almost a year ago but held on to it for fear of being described as angry (another convenient American stereotype of Arabs and Palestinians). Now that my second book, Border Wisdom, has found a home, I take this opportunity to unburden myself of the heavy ironies I detail here, ironies which continue to govern the lives of Palestinians and other similarly unrecognized and easily dispensable minorities in the US. I would also like to celebrate small, independent publishers like Winter Editions and to express my deep gratitude to brave dedicated editors-poets like Matvei Yankelevich, who are uncompromisingly invested in poetry above all. Thank you for giving me the gift of your sincere critical engagement with my work.

We, Palestinians, are nothing at all, not a minority, not a model minority for sure, just some nuisance from the Middle East—that vague unsettling category that even the most educated of Americans might know almost nothing about.

Ahmad Almallah

When my first poetry collection, Bitter English, was published in 2019, I was a newcomer to the American poetry scene, even to English. I didn’t know what to expect from the publishing experience. I was happy to finally see my work in print, published in a prestigious poetry series, after many years of disappointment. I had no real interaction with the editors who remain anonymous to me to this day. I had little say in the process, even when it came to the cover of the book. I was chosen and I had to be grateful.

As I prepared to share my second manuscript, the press requested that I hold off due to ongoing major changes within the series. These changes were being implemented in response to significant shifts like the Black Lives Matter movement, the #MeToo movement, and the growing demand for transparency and accountability in the publishing industry. The changes were hailed as the inception of a new, ostensibly more democratic process. Filled with hope, I eagerly awaited the right moment to submit my manuscript. However, as time progressed, my hope began to waver. After many follow-ups and extended periods of silence and evasion, the newly appointed series editor explained to me the new system. Decisions were to be made through the unanimous agreement of an editing committee which granted each of its members the authority to exercise a veto over any submission. I told myself, against the comforting of others who told me to wait and see, that there was no way my book would be “agreed upon unanimously.”

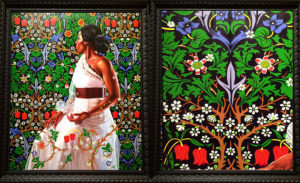

Poetry — certainly my own, I hope — doesn’t aim to be a unanimously approved “beautiful manuscript,” as the celebrated new editor put it. Poetry is measured by its transformation of language into something real. Poetry has never been a decorative art. Its lasting effect is measured by the challenge it poses to common ideas of beauty. But the motivation for writing this letter is not to explain what poetry is — this I’m afraid is a matter irrelevant to the American poetry scene, which is so isolated from other poetic traditions, and maybe seeks to remain that way by merely incorporating others through the decorative act of token inclusion as the optics demand, so to speak.

When finally, after months of evasion, my manuscript was rejected, I wasn’t really surprised. Instead, I found myself perplexed by the multitude of ironies that had paved the way for this decision, many of which were evident right from the outset. With this open letter, I aim to reveal and document these paradoxes that underpin the decision to exclude an individual of Arab-Muslim-Palestinian origin (or whichever ideological category this system designates for me) from an established poetry series, all in the name of promoting inclusivity and diversity.

How ironic it is that a new poetry editor and a committee instated to bring diversity to an “old system,” begin their work by excluding one of the few other voices that the old system had allowed. More alarmingly, how convenient and easy this decision must have been, since Arabs, Muslims, and especially Palestinians, are so marginal in the American cultural scene that they are used for diversity and removed from diversity whenever convenient, without the twitch of an eye. The American cultural scene seems to consider the feelings of every minority, except that of Palestinians. Maybe it’s because we ideologically do not exist as a political entity, even to be designated officially as a minority. And the “optics” allow it. As someone in the street once shouted at a Palestinian friend of mine: “What are you?! You’re not white, you’re not black! Get the fuck out of here!!”

These are the same racial terms that motivate the elite cultural scene. It is not a real interest in bringing justice to underprivileged or underrepresented communities but an attempt to contain them by “including” them through a game of visuals and optics that institutions play for their benefit, and their benefit only. We Palestinians are nothing at all, not a minority, not a model minority for sure, just some nuisance from the Middle East — that vague unsettling category that even the most educated of Americans might know almost nothing about.

In the curt note, the editor rejected my manuscript and thanked me for work we had done together in Poetry magazine. In the months while my manuscript sat on his desk and I anxiously waited, trusting in a new democratic system, he invited me to contribute to a special issue of Poetry magazine, and here comes another irony to point out. It took us months of constant communications (emails, texts, and phone calls) to iron out a few pages of prose, to make sure that the piece was digestible to Poetry readers. All the while, I assumed that my manuscript must be getting at least some such care and attention from this editor who is so attuned to reader sensitivities. But, after months of waiting, I get a few lines in an email, telling me that my book was not among the many “beautiful manuscripts” they received. My second book, which took years to write, did not warrant a single comment, not one reference to a poem, or even a line, as though it was a book with a title only. No feedback whatsoever…just the recourse to the oldest trick in the book for excluding people — referencing some vague abstract standard, beauty in this case, that the work failed to attain.

After the months during which we interacted on the Poetry article, exchanging emails and messages that were signed with warmth and admiration…suddenly, it was all over. No human interaction was further needed. I was out, game over. I now wonder whether the committee even read the manuscript at all?! A new order was being formed, and there was no place for me in the optics of the new set up. The decision was communicated to me as succinctly as possible. I guess the democratic process needs to be spelled out in the tersest of terms. We recognize only to eliminate. I am all too familiar as a Palestinian with this parallel democratic system, named on my land as Israel, where “democratic” laws are made for the elimination of Palestine, where the colonial process hides its ugly face through similar optics. It’s so hard to call something what it is in the US, and it is so easy to level lies against the Arab, Muslim, and Palestinian communities. They are an easy target and it’s so easy to look the other way when it comes to their exclusions. This is precisely the reason why I felt compelled to write this letter: to reveal the double-standards we are constantly victims of as an unrecognized minority in the US publishing machine.

And there were signs that I only realized in retrospect. While working together on the Poetry article I received a fact checker comment replacing “Palestine” with the phrase “West Bank.” I should have known from the editor’s response to my outrage, I should have known then and there what the destiny of my book manuscript was going to be. I wrote to him in disbelief that after all the work and the back and forth I was getting that blatant note of erasure. “What can we do? These things happen,” he simply responded. He was willing to let it slide! He was hesitant to challenge his readers in Poetry. Why then did I expect him to challenge them when choosing poetry manuscripts for his new series, when there are much easier, more recognizable, and less problematic ways of being diverse and inclusive in the US?

Let me point out the biggest irony for us — as immigrants and people of color. Why is it that sometimes when a person of color makes it to a position of perceived power in the publishing industry, they end up upholding the skewed standards, which might have been used to exclude people like them, as strictly and arbitrarily as their discriminators, if not more? Is it a way of proving that they deserved to have made it through the firewall? For often, people of color are placed in positions of seeming power, only to reinforce the fiction of diversity for the elite; to reinforce a systemic network of convenient discriminations, and they accept these roles as if they were medals of honor. If they truly believe that the optics they’ve been roped into produce “beauty,” then they are delusional. If they know of its discriminations and are still willing to participate in the sham and advocate for its so-called purity and transparency, then they are hypocrites.

And isn’t this exactly what tokenism is: selective inclusion, a silencing tactic? “But he included you there” some will say, and some did say, “why can’t you believe in the democratic process and its outcomes here?” I don’t need to repeat myself: I’m all too familiar as a Palestinian with this trick and how the “democratic process” when put in place on colonial/fascist grounds can only produce misery and injustice. When a system of so-called inclusion gives each one of its members veto power, i.e. the absolute power to stand in the way of publishing any work, this means that each of the individuals who make it to the top has much more power than the system will lead us to believe. And in the name of vague and abstract notions such as “beauty,” their power is practiced unchecked and with no accountability whatsoever.

We have in practice replaced a mysterious anonymous body of editors with a new system in which the unanimous (and supposedly transparent) vote grants the editors absolute power under the cover of diversity, democracy, and inclusivity … how is that better than the “old” system?! The entire production appears to be more colorful and diverse. An inconvenient other can be easily replaced with another more palatable other, and the show of diversity and inclusion goes on.

I have only the words of my favorite American poet to end with, that poet who knew that her talent would only be corrupted by catering to the world of publishing. Emily Dickinson sought to write something real, and never got to see her work recognized during her lifetime. Eventually the world of poetry will shed all that noise, all the optics and the petty dynamics of publishing and will only recognize and preserve voices like hers. Behold her words:

Publication — is the Auction,

Of the mind of man —

Poverty — be justifying

For so foul a thing

Possibly — but We — would rather

From Our Garret go

White – Unto the White Creator

Than invest — our snow —

Thought belong to Him who gave it-

Then — to Him Who bear

Its Corporeal illustration—Sell

The Royal Air —In the Parcel — Be the Merchant

Of the Heavenly Grace—

But Reduce no Human Spirit

To Disgrace of Price —

Dear Ahmad, I have just read your Open Letter: On Being Arab/Muslim/Palestinian and Publishing Poetry in the US, 21 August, 2023 • Ahmad Almallah, published by The Markaz Review. Thank you for your essay.

Although the open beauty of your grief fills my senses with compassion – I am equally dismayed by your truth. Not to say that it is flawed. It is not. It belongs to you; and your point is clear, as you stand on hard-won American soil, tasting its sweetness – with your toes embedded still in the wadis. I get it! Yet, you leave me bewildered. Even saddened – that at this point in your life, with all the accomplishment that I see in your future, your pen still flows with the purple ink of perceived entitlement – like a thirteen year old.

Ahmad (beloved brother) could someone as talented as you, have so much sand in their eyes that they cannot see how the issue you lament is planted (even nourished and watered) in the heart of man? Do you not perceive how it sneaks across borders and cultures (well beyond our ancestors) and has done so from the beginning of time? If not – try a “spotting scope” in place of your binoculars. You describe the trek of every artist – crossing all disciplines. This is the process internationally. Work it! Use it creatively and get on with the task at hand. Your struggle is not unique, and I urge you to whine to your heart’s content until you pass through puberty. Then, kindly, jump start the flourishing career that awaits you, with the gratitude of adulthood. Lastly, remember the words of King Solomon, “Above all else, guard your heart, for it determines the course of your life”. Proverbs 4:23

God bless your writing. Through your troubled honesty, my hope is that you will pen a glorious path through that bloody briar of rejections … until you land at the top of the pile; where the opinion of an editor will hardly be a trickle – like water on a ducks feathers.

Warm wishes, Julienne (Jabara/Mohammed) Johnson

International Museum Artist/Curator, Poet and Award Winning Songwriter, August 21, 2023

P.S. I continue to have admiration for the Jews, whose answer to the oppression of not being served in American hospitals in the mid-1800s (among other injustices) was to build their own – better, going on to serve their own needs with such excellence that those doctors and the inimitable care provided at those hospitals was in demand, serving all who entered – regardless of their heritage or status, as they continue to do today.

I find this comment quite disturbing.

This resonates and is true in many domains, not just poetry publishing.

Well said.

But we DO exist, and we carry on, despite everything.