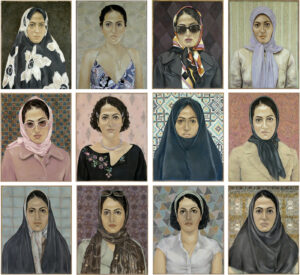

All these years we’d gotten used to playing around with our hijab when we were acting. The hijab was our prop. Now it was our own hair. When I no longer had that piece of cloth pressing on me, the feeling was completely different. Now whenever my hand reached for my head, for any reason at all, I’d freeze. I’d literally freeze. It was a really strange and new feeling. My own hair was a stranger. And to this day I still haven’t been entirely successful in dealing with the absence of the hijab when I’m on stage.

Her Instagram page said, We’ll have three shows next week. If you want to attend, send a message to this here page. I sent the message. She sent me a WhatsApp number and said that I should let them know I was her friend and wanted to buy a ticket. I followed her instructions. An answer came giving me the time and place of the performance. There was also the number of a bank account to which I could send the money for the ticket. Again I followed the instructions. A second message came — on such and such date, and time, there would be a seat waiting for me at the theatre.

I knew that address. This was no underground theatre, but rather a very well-known establishment. I started to wonder if I’d been had. How could an underground performance be taking place in such a recognized place? On the night of the play I got there early and saw there was already a large crowd waiting outside. My suspicion grew, both about the performance and about my friend’s very public announcement that she was never going to act in plays and films which had official permission and therefore required an actress to wear hijab.

I spotted an acquaintance and asked if she too had come because of the Instagram announcement. She said yes and seemed to generally know more about what was happening than I did. At least she knew who the playwright and the director were. Inside, they didn’t give us any program notes. I found a seat and kept my eyes on the actors, all of whom were already sitting with their backs against the stage wall waiting. None of the actresses wore hijab, including my friend who wore a simple short skirt, sleeveless shirt and stockings. There were easily over 300 people in the auditorium. A stage-hand stepped up and addressed the audience, asking that we turn our cellphones off or put them in airplane mode. Absolutely no photographs were permitted.

The play began. At first an elegantly dressed woman with bare, shoulder-length black hair stood at center stage and read from a text that seemed to be a replacement for the brochure we had not been given. It didn’t take long into the performance before I understood that the piece was about the first real revolution we’d had some one-hundred years ago, a seminal movement which affects all of our lives to this day. But then the play took a detour and purposefully mixed its revolutions so that we ended up in the recent time of the Woman, Life, Freedom demonstrations. Before long my friend was on stage. What she did next was a first, for me at least. Her role called for the unpeeling of her stockings, which she proceeded to do. I looked about me and saw that everyone in the audience had the same look that seemed to say, “What if the morality police are waiting in the wings? What if they’re about to swarm inside and arrest all of us?” What were they going to do to my friend up there on that stage? The minutes passed, nothing happened, and by and by I got sucked into the narrative. By the time it was over, I had already decided I was going to interview my friend about her experiences as an actress over the past year and a half. More importantly, I would make a point of asking her what it felt like to no longer wear a hijab on stage and no longer play parts that required the customary official go-ahead.

This is the conversation we had:

What made you decide to finally do away with the compulsory hijab on stage and not act in any theatre or cinema that has to pass authorized channels first?

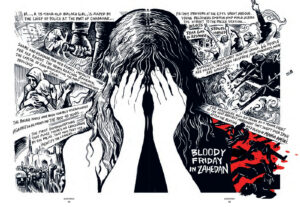

It was about three or four months after Mahsa Amini’s death and there were daily confrontations on the streets. I had a part in a play back then and our space was right in the middle of all the street battles. It was a good theatre piece too, and I think had things been normal it would have done really well and the show would have been extended. Back then I thought I was doing something courageous just to walk through the police lines to get to the theatre to do my job. Then one day I thought about how absurd the whole thing was. Imagine: I was defiantly walking without a headcover on the streets, past the road blocks and the cops, only to arrive at the theatre to play my part with a hijab on. It made no sense. It meant, whether I liked it or not, I was still working for the “man,” so to speak. This had to stop. Then came a trigger that sealed my decision. In the middle of one of our performances, we heard gun shots coming from right outside where we were. Imagine, we’re acting inside the theatre and gunshots are going off next to us. Everyone inside, the players and the audience, were dumbstruck and silenced. Afterwards, one of the actors who was in a particularly bad way wanted to know just what the hell we were doing here.

It was like being hit with ice cold water, a wakeup call. Because, really, what good were we inside this theatre? Either we had to be out there with the people, or if we were going to go on with our jobs, then we had to do it in a way that made a real difference.

Some time has passed since those days. The movement, for what it’s worth, is fairly quiet now. My question is, do you think under these circumstances refusing to do theatre where you have to wear hijab or refusing to act in officially licensed films makes any difference at all at this point?

Some people say the regime is happy that less theatre is happening these days. I don’t care for this bleak view. In a situation where only a portion of the women in the big cities are continuing to go hijabless, it’s art’s job to show that things can’t go on as before. If it wasn’t for the handful of films made during this period where none wore hijab, you’d think our movement never happened. It’s our responsibility, especially today, to scream out loud and clear that nothing is normal, nothing is what it seems.

But how about yourself? What will become of all the dreams you’ve had for becoming an established actress in cinema and theatre?

There was a time when acting for me was everything. All I wanted was to act and be able to make a living at it. Now I think there’s something far bigger involved. I’m no longer so caught up in wanting to make a name for myself. I won’t deny I’m being offered far fewer jobs now than before. And even the roles that they do offer me without hijab, I’m not always crazy about. So the pickings are slim, yes. But when your life’s purpose changes, when it changes into deciding to live the way you want and not how others dictate you live, that’s something. Sometimes I ask myself why I didn’t do all of this long before Mahsa’s death? We all knew there was so much that was unjust and biased, but we went along with it. If there was to be a way to go back in time, I’d make a lot of decisions differently. I’d never agree to take on roles which went against my lifestyle and principles.

I’m curious, since you are no longer accepting roles which demand you wear a hijab, have you become less selective about roles where you don’t have to cover your hair?

On the contrary. I’ve become even more selective than before. In the past, I told myself I shouldn’t be too picky about the parts I get until I make it in the business. Today I tell myself I have a purpose for staying in this profession. There is a reason I’m here. Which means if I’m offered a role that goes against my aspirations, I won’t go along with it. I’ve already passed on five roles where they didn’t require me to wear a hijab. A few years ago I probably would have accepted these roles. I would have accepted them even if I had to wear a hijab. What I’m trying to say is that my decision to be an activist has actually made me more rigorous about what I accept and don’t accept. I’m especially choosy about what I take on in cinema. With theatre I’m a bit less picky. Theatre is a different animal. Even a small role on stage, day in and day out, keeps you on your toes as an actor. You stay warmed up and get a lot more out of it than in film.

Do you believe artists have a special mission they need to follow?

Nowadays, yes, I do believe in this concept. Before I used to think you should just do your own thing and focus on your art. This no longer works for me. It’s not enough. Us common folk can make only so much difference as individuals. But any well-known artist, I feel, has an obligation to give back by using their platform to support the people, the fans, who have put them there. Especially the men among us could be doing more. Now, I’m not saying men haven’t done their part during our movement, but the fact is that it is women who have carried the weight and pushed the envelope. The number of women who have refused to work under the status quo far surpasses the men.

What’s been the reaction of your friends and colleagues to your decision?

A lot of people imagine they need to advise or warn me. Usually they’ll begin with something like, “You were on the cusp of a breakthrough in your career. You were right there, about to have everything you ever wanted. Are you sure about your decision?” A close friend even offered me a job for a voice-over on a film that had the blessing of the regime. It paid very well too. He told me, “Take the money. In fact, this is what you should be doing, taking their money so you can do whatever you want with it afterwards.” I told him no. I told him, “Actually this is precisely the time not to take their money. This is the time not to sell out.”

So you’re willing to stick to your decision even if it means having to do work other than acting to make ends meet?

Let me make clear that I’m not exactly happy about so much of this. For instance, this friend who offered me the voice-over job said, “Do you really think you’re making a difference? How about first you make a little name for yourself, become influential and then you start making these kinds of decisions.” I told him I wasn’t after fame or influence. I’m just a woman who wants to go her own way and live life the way she wants to live, and not what others prescribe for me. So what if I don’t influence others? At least I can work on myself, can’t I? Maybe if more of us thought this way rather than prioritizing influence, things might have been better a lot earlier. As long as I recall, we’ve all been repeating the same useless mantra: “There’s nothing I can do on my own.”

Well, a lot of people are still saying that nothing much has changed. The economy has tanked and people have serious money worries. Under these circumstances, aren’t there far less actors remaining as dedicated to the cause as you are?

If anything, it’s the exact opposite. In those heady early days, it was expected that more well-known artists would make these kinds of decisions. We all truly believe this was the beginning of the end. But things didn’t turn out that way. Now, the realization has set in that the regime is not going anywhere, so I — we — have to stick to what we think is right. People are making their choices with more awareness. I might last another year or two like this, and I may have to pay a big price for my choices. For someone like me who has no intention of leaving the country, someone who wants to stay right here to live and work, I may even have to end up giving up acting altogether. I’m all right with that. This newfound freedom has made me rethink everything. It’s liberty that’s priority for me now, not becoming an actress who makes it big at any cost.

What has changed in theatre ever since Woman, Life, Freedom? I mean, besides deciding to go without hijab.

I can most definitely feel this: men’s respect for us women has exponentially grown. A lot of other things may not have changed so much, but there’s that look in men’s eyes that says, “We respect the road you’ve taken.”

What are some of the personal difficulties in going on stage without a hijab?

We used to think that even with hijab on, we were giving it our one-hundred percent on stage. Now I’m seeing that that’s simply not true. There are a ton of things I haven’t any experience with and which are hard for me to do still. You saw that in this play I took my stockings off so that my legs were entirely naked. During practice I used to say to myself, I’ll just keep them on for now and take them off when I have to perform in front of a real audience. It won’t make a difference. But it did make a difference. I’ve never had any trouble wearing revealing clothes when I’ve gone to parties. But I’d never gone on stage and bared myself like that for a whole audience. It was not easy for me. Another example was the sudden opportunity to have my hair be a part of what I could do with my body. All these years we’d gotten used to playing around with our hijab when we were acting. The hijab was our prop. Now it was our own hair. When I no longer had that piece of cloth pressing on me, the feeling was completely different. Now whenever my hand reached for my head, for any reason at all, I’d freeze. I’d literally freeze. It was a really strange and new feeling. My own hair was a stranger. And to this day I still haven’t been entirely successful in dealing with the absence of the hijab when I’m on stage.

Now imagine that the new film I’m also acting in has several love scenes in it. Something as simple as leaning my head on my male counterpart’s shoulder is proving difficult for me. I’m not used to anything remotely close to that. One of the other film offers I rejected lately had a pretty intimate scene that I simply could not see myself playing. Truth is, I didn’t think that intimate scene was so necessary. What I mean is, all right yes, we do need to be true to ourselves, but there are red lines that, at this point, if we cross we’ll lose a lot of the people who are sympathetic to our cause. I grant that my point of view might seem conservative, even fearful and cowardly, but all the time I’m thinking about expanding our base of supporters. The scene in question could have easily been wrapped up with an embrace rather than a full-blown love scene. I wasn’t comfortable with it. Nevertheless, with the passage of time, I imagine all of this stuff will get easier for us. That goes for our male counterparts as well. They too are not used to us putting our heads on their shoulders, let alone playing a love scene. All in all, I still feel there’s a very long way to go. I still freeze when it comes to certain intimate moments in acting. It will take a lot of practice to get past that, but I see myself getting a little better at it every day.

You’ve had to deal with a lot, it seems. Dealing with it totally alone.

No, not alone. My family too has been involved in this process from the beginning. One can never know how one’s family is going to react. My own family never stood in my way of doing what I had to do, but they didn’t encourage me either. I think not giving outright support was their way of not wanting me to feel invincible so as to bring more trouble to myself. Nevertheless, they still try to show support by, say, liking or putting a heart emoji on Instagram next to a trailer for a film I happen to be in. It’s complicated, especially for the men in our families. All their lives they’ve been taught that they are our protectors and there are red lines they have to watch out for because we, their women, must not be disrespected or abused in any way. But what exactly are those red lines at this point? I don’t know anymore. This makes things doubly hard for a woman like me, particularly when it comes to my father whom I never want to dishearten. He doesn’t deserve it.

How precisely has your father supported you?

After Mahsa’s death and the demonstrations that followed it, I finally took a trip back to my hometown for the first time. I’m talking about a conservative place far from the free-for-all of Tehran, a place where I didn’t see one other woman walking down the street without a hijab. That first day during lunch with the family I told my father it was not possible for me to wear a hijab any longer. If he insisted that I wear one when we went out on the street, I’d just as gladly stay home the whole time during my visit until I went back to Tehran. For a traditional man like my dad, a man whose entire life was bound with this traditionalist place and its culture, it was a huge move, a foundational one, to step outside into the streets of our town with his daughter walking bareheaded by his side. And this he did. An act which was nothing less than a revolution, and one which one day I would love to play on screen. You have to imagine that at that lunch when I told him I would either go outside without a head-cover or not go at all, what went through him. He sighed. Deeply. But it wasn’t a grumble or a reprimand. It was more like worry for his daughter and for the choice of the journey she had embarked on. A worry at the thought of not being able to protect her when the time came. A worry that reminded him of those parents who were not able to protect their children, post-Mahsa, and lost them forever.

I call what my father did for me heroic. Just the fact that from day-one he never stood in my way, never told me what to do or not to do, that is true support. I can even imagine him one day standing tall in the middle of the square of our town and shouting to the world: “No, none of you has a right to tell my daughter what to do. None of you has the right take away her freedom.”

You have to understand the significance of all this. Here you have a man who has gone against everything his upbringing, his culture, and his townspeople tell him. When all the men around us told him not to allow his daughter to go to the big city for college, he refused to listen to them. When they told him it was time for her to get married and settle down, he paid them no mind. Instead, what did he do? He walked side-by-side with his hijabless daughter on the streets of his little town and the next day he took his daughter to a family wedding where she danced bareheaded with him in front of everyone. It is because of this father that no one dares tell me to pull my headscarf on in my hometown. I’ve always had the protection of this man who raised me. For this, and for so many other things that I am grateful for, it is not easy for me to fly in the face of all his understanding and compassion by agreeing to a role where I have to play a lovemaking scene. I just don’t have it in me yet to see his pain if something like that were to ever be shown. On the one hand, I tell myself it’s my right to do whatever I want, play any role that I feel suits me; on the other hand, how can I be the cause of shame for a traditional man who has gone so far out of his way and his comfort zone to support his daughter? It’s a delicate balance. How do I stay true to myself and my profession, and at the same time don’t cause an irrevocable rift between my father, my brothers and all the people who care about me?

The night I came to watch you in that play and saw the sold-out crowd outside waiting to get in, I asked myself: How is it possible that this troupe can perform underground in this space? Now I ask you the same thing — how is such a thing possible in the Islamic Republic?

I admit I’ve heard from a lot of people asking the same question. People have even accused us of collaborating with the government somehow, otherwise how could we be allowed to perform so freely. My thoughts on the issue go like this: by now the regime knows it has no choice but to let some things go. Us women going without hijab on the streets is one of those things. It’s the same with theatre. In the beginning, I too asked myself why they were allowing us to perform so freely. The answer is simple. They know that if they stop us from performing here, we’ll simply find another way and another venue to do what we need to do. The regime doesn’t have the logistics to stop everybody everywhere all of the time. In truth, even on the occasions they put their uniforms out there on the streets to warn us about hijab, it’s more for the sake of appeasing the extremists among their own constituency. More than anything, the regime simply doesn’t want the trouble and the headache. It doesn’t want people to get together and amass. Tell a woman at the entrance of a metro station in Tehran to put on hijab and you’ll have ten people within seconds raising hell and pushing back. The authorities know this. That’s why when folk start arguing with them, you’ll hear them say, “Just go away, go!” They don’t press the issue. Their ultimate goal is to remain in power, which means they don’t want trouble from us. We may be scared at times. But so are they. They’ve made a tactical retreat.

Finally, what do you think is the role of the audiences, the people who come to see these plays and films?

The day you came to see the play, afterwards one of the women in the audience came up and said to me, “From a certain point on, I guess after you took of your stockings, I could not take my eyes off of you because I was worried. Worried what would happen to you. It felt like you were taking too much risk, sacrificing too much. What it felt like was you were out there on those streets again fighting, fighting for all of us.” When this woman told me that, I knew once and for all that my choice had been the right choice all along. I had made a difference. Often it happens people tell me that since we refuse to act in officially permitted plays, they too won’t go to see those kinds of plays either. They’ll boycott them. It’s as if the experience of seeing theatre like ours opens a whole new lens to the world for them. And because of this, it’s no longer just about hijab or getting someone’s permission to perform. It’s about learning from each other to have courage to do the right thing. It’s about witnessing that there are people out there who are willing to put their lives and their careers on the line. And if these people are willing to do that, so is the person coming to see the performance. The spectator is no longer just a passive agent; it’s their turn now to make that choice, to have agency, and to make change.

Please keep me posted on your events