The Lebanese artist’s almost messianic dedication to pacifism and social justice drove his passion for painting and the creation of large murals across several decades.

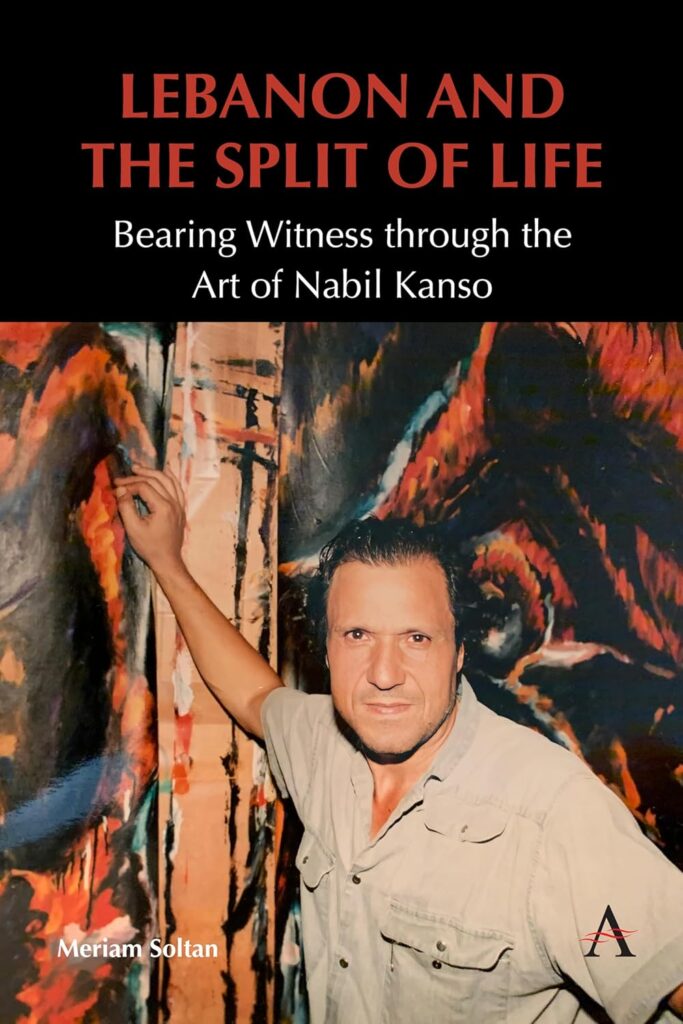

Lebanon and the Split of Life — Bearing Witness through the Art of Nabil Kanso, by Meriam Soltan

Anthem Press 2024

ISBN:9781839989636

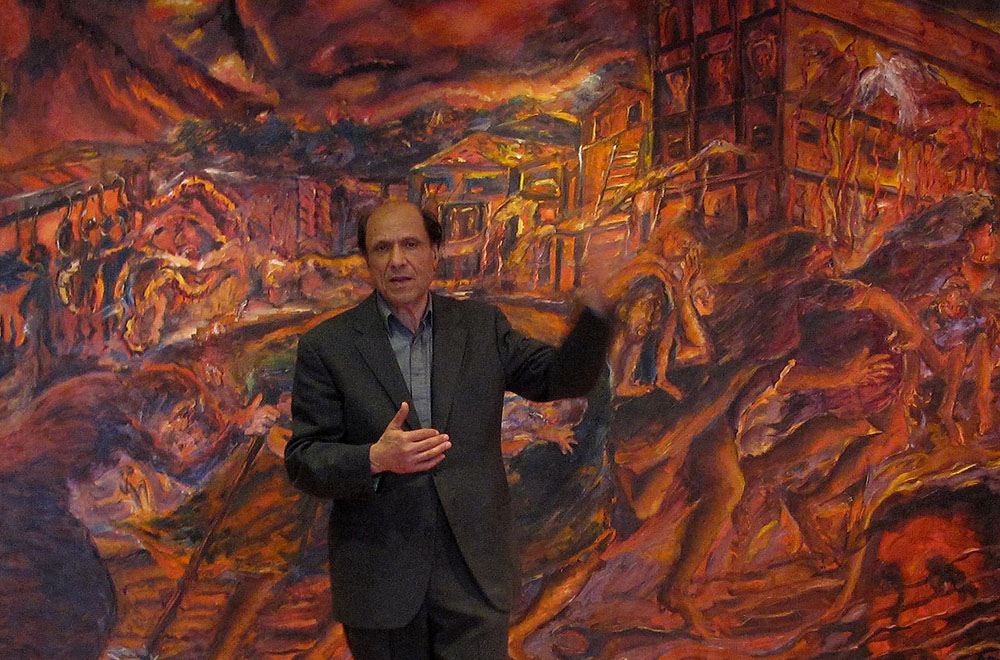

The life of Lebanese American activist artist Nabil Kanso is the subject of a new biography that explores the artist’s life through his work. Kanso’s paintings are steeped in a dark existentialism that recall the symbolic complexities of Hieronymus Bosch or Pieter Brueghel. Much of Meriam Soltan’s Lebanon and the Split of Life is based upon the extensive archive left by the artist to his family in Atlanta, Georgia, where he lived since 1980. Soltan builds a narrative around this creative and deeply contemplative family man who, as an artist, tuned in to the voices of the past and to the torments of history.

Nabil Kanso (1940-2019) was born in a peaceful Lebanon. He was three years old when the country gained its independence in 1943. Nonetheless, tensions were brewing throughout his teens with the US invasion of Lebanon in 1958 and the rise of Arab nationalism in Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Egypt. For the Dalloul Art Foundation, Lubna Akram recounts a story that the artist was fond of telling. The young Kanso had been holding a camera when he was confronted by a soldier who informed him that “’a camera could be more dangerous than a gun.’ This experience prompted him to start drawing.”

Conflict raged in his native Lebanon, and so the artist moved to London in his late teens to study architecture, then to New York in the 1960s. Ironically, the US had its own set of political threats, amongst them the nuclear arms race against the Soviet Union, and conflicts such as the Vietnam, Korea and Gulf wars. But Kanso never looked back and he continued to draw inspiration for his art from the turbulence of the era.

Soltan observed that although the artist’s works during his early period were unremarkable, his talent was recognized by the wealthy American patron Dorothy Whitcomb, with whom Kanso founded an exhibiting gallery space, the 76th Street Gallery, in New York. She was inspired by Kanso’s work and his creativity. Though politics and visual culture were constants in his life, Soltan suggests that Whitcomb’s connection to the artist rested on his sensitive and intuitive treatment of the female form. Nothing more is mentioned of this sensitive rapport though Soltan tells us that the artist maintained a continued focus on women and mythology. It was through Whitcomb that Kanso came into contact with many influential people of the American art scene in the 1960s and 1970s. He would also become more socially and politically aware, completing first undergraduate and masters degrees in art history, and then a masters in political science, before developing his art practice.

Themes of confrontation and struggle would remain an intrinsic part of Kanso’s art and the title of Soltan’s book, Lebanon and the Split of Life, refers to the series of 88 paintings which the artist worked on from 1975 to the 1990s. The images are filled with the horrors of war, man’s inhumanity to man, and recurring feminine themes suggesting family ties or internal conflicts, and celestial references to divine providence. These may be attributed to the artist’s Druze mysticism, a faith linked to Sufism and Islam, which includes a belief in reincarnation. They could also be connected to the stories told amongst the Lebanese diaspora in the US or that he heard on his brief visits back to Lebanon throughout the war. After 1975 — perhaps encouraged by the horrifying stories of the Lebanese civil war — Kanso’s paintings became increasingly existential, depicting political scenes inspired by news reports, a mood of civil rights and resistance. This brand of artistic militancy would become a continuous narrative in his work, whether it was about the war in Korea, the invasion of Iraq, apartheid in South Africa, or the US civil rights movement.

Kanso traveled much throughout his life, and this explains the rich material and ideas in his narrative works. The result of many hours of solitary reflection and painting, Kanso’s works and the Split of Life series in particular (including “Lebanon, 1983”) are just as much related to his ideas as they were depictions of particular incidents or news items.

Kanso’s powerful paintings tell a variety of stories with strong, expressive characters. In “Lebanon, 1983,” he portrays a mother holding a child on her shoulders, a floating and another drowning woman. Each of these figures seem to be reaching out for the glowing white light of peace. Spurred on by the fall of Saigon in April 1975, which not only marked the end of the Vietnam war but also the beginning of the civil war in Lebanon, Kanso began to paint massive mural-scale canvases. These looming, frieze-like works form an important part of the artist’s legacy today. They portray the savagery of war, protest, defiance and salvation. Kanso described them as “mobile murals” — most likely in reference to the movement that they capture, a form of anti-war protest.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating twists in Soltan’s story of Nabil Kanso is that the artist was not at all motivated by gallery sales. His “lack of an audience for these later series, although demeaning, never deterred him.” As an artist, he was strongly drawn to portraying the messy turmoil and injustices of war. He needed to paint. This was like a calling or a duty to communicate injustice, rather than simply recording scenes for posterity.

It is fascinating to read about an artist whose need to express these situations or unfolding horrors seem almost messianic. Soltan explores the artist’s intentions and psychology in her close reading of “Lebanon,” a massive work completed in 1983. She plots the undeniable influences of Picasso’s “Guernica” (1937), Goya’s “Disasters of War” (1810–20) and Lebanese Modern artist Aref El Rayess’s “Road for Peace” (1978) in the artist’s vibrant tableaux, which explore themes of unfairness, hostility and fear. The brutality of man struck an important chord with Kanso, even if it meant alienating the casual art audience. People were not ready for him to hold a mirror up to their societies, Soltan suggests, and these are not simply history paintings. Paintings depicting Kanso’s own country’s agonizing implosion over 15 years of bloody civil war are filled with a personal anguish that are heartbreaking in their drama and expressions of desperation and loss.

Kanso was not only ahead of his time but could also be described as something of a futurist or a prophet. He traveled throughout North and South America in the 1980s and 1990s, mounting exhibitions in peace-building centers, halls and not-for-profit organizations, which shared his interest in his quest and determination for peace. The Journey of Art for Peace series traveled widely and “America 500 Years: Bleeding Eagles,” 1989–1992 is a hard-hitting commentary on the realities of America’s brutal removal of native peoples around the time of the first Gulf War in 1990. It was after this period, Soltan tells us, that Kanso stopped exhibiting his work to the public even though he continued to paint.

Since his death in 2019, the Nabil Kanso Estate maintains an extensive archive of paintings and rolled canvases created in his studio. The Association for Art of the Arab World, Iran and Turkey (AMCA) supported Soltan’s research and the estate has been active in making Kanso’s archive available for scholarship. Soltan writes passionately and sensitively about the artist’s struggles and suggests a new relevance of his work in modern times. For example, the interwoven ideas in his painting series, The Golden Age of Lebanon (currently in the Sardar Collection) allow Kanso’s memories of the country during his youth to shine through. The reader is allowed to explore these and Soltan offers insight into the socio-political instability and religious fervors of the Lebanese civil war which inform the work and explain his handling of subjects, compositions and themes.

It would have been interesting to learn more about the man himself, from his wife, friends and children, however the author’s focus on Kanso’s work as a lens through which to tell his story is captivating and bewitching. Soltan considers the relevance of Kanso’s work now and in the years to come, and notes that the artist refused to sell his work, which in later years he referred to as “his children.” In later life, Kanso withdrew into his work. His desire to produce and to testify to events as if to keep a record of them, seems at odds with their being packed away in storage and out of sight. As a result, decades of paintings and works on paper were packed up and kept, never to be exhibited. Some of these have only recently been seen by the writer and by Kanso’s children. In order to create such formidable works, this passionate artist must also have been quite a distant husband and father, though none of this is touched upon. The book focuses instead on Kanso’s magnum opus magnus, The Split of Life series, as a way of bearing witness to his legacy.

In The Split of Life series, there is a sense that misdemeanors and behavior are being exposed, as if on trial. This fascination with humanity in all its forms, may explain the artist’s interest in Latin America and other countries at war, politically and historically, as subject matter in his practice. In a sense, the parallels made between countries at war and injustices, were also a way to return to his Lebanese homeland and to his beginnings.

The spiritual and divine nature of Kanso’s work is emphasized by his own words: “Art brought out more in me than anything else I’d ever experience.”

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)