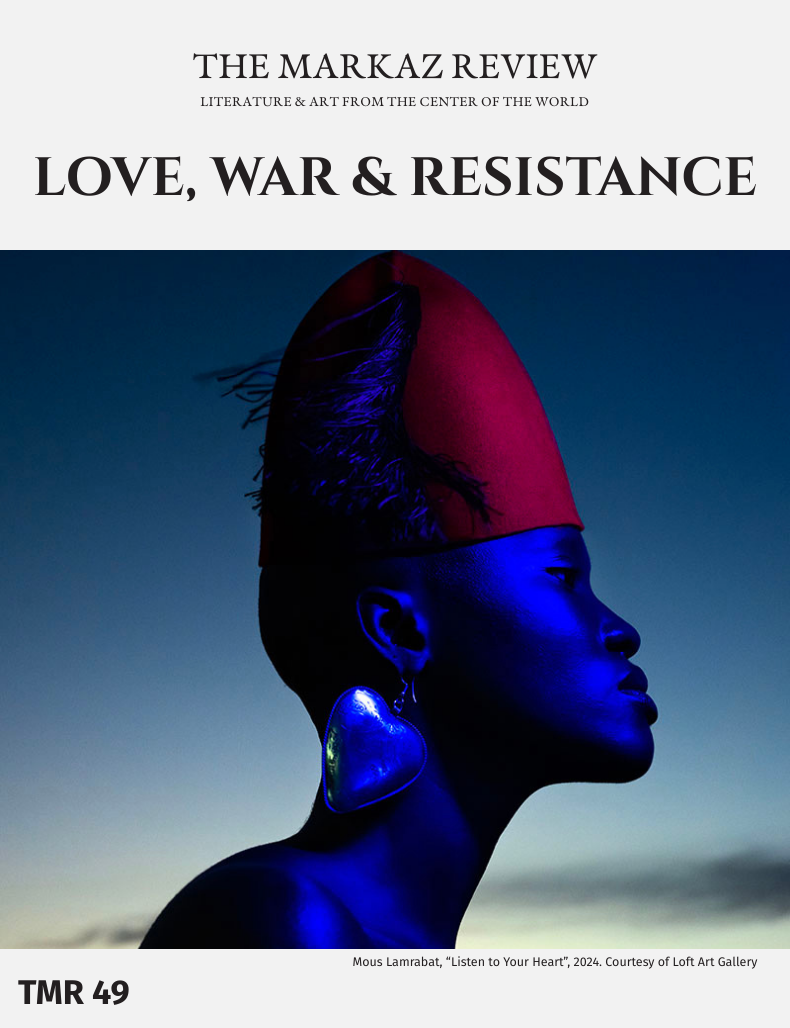

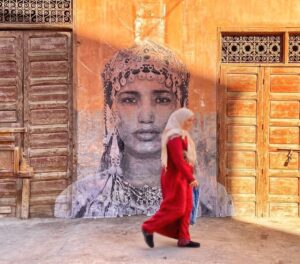

Featured artist for March 2025, The Markaz Review showcases Mous Lamrabat’s solo show, Homesick, now at Loft Art Gallery in Marrakech through the 15th of March. The series is a striking meditation on identity, nostalgia, and cultural fusion. Through twenty powerful new works, the Moroccan-Belgian photographer reimagines heritage with contemporary aesthetics, bridging past and present in an emotional exploration of belonging.

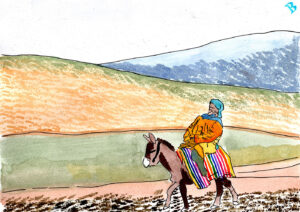

An amazon-like figure looks at me from beyond a glass frame. She sits proudly on a donkey in the middle of the desert, wearing a futuristic golden helmet with wings. Her stare reflects defiance and pride, even though she is not necessarily riding the noblest steed. The photograph is called “Mariam Had a Little Donkey,” and I experience a minute of deep connection with this lone rider. A second after, I’m carried away by the crowd on the rooftop of the gallery where the show is taking place.

It’s the night of the galleries in Marrakech, and the rooftop of Loft Gallery, where the show of Belgian-Moroccan photographer Mous Lamrabat is taking place, is overlooking the modernist neighborhood of Gueliz. Here, several art spaces have set foot, participating in an artistic renaissance, which is making Marrakech one of the places to be of contemporary art, alongside Athens and Marseille; all the cities where the Mediterranean instances are creating a new kind of coolness.

Mous Lambabat’s show, Homesick, is taking place during the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, a coherent choice, given that the whole Marrakech art scene is in the process of strengthening its cultural connection with the wider Africa. The show speaks of an expanded sense of home and community, and the glam element of the vernissage night didn’t dim at all a widespread sensation in the Moroccan city, namely the one of being home, of being one big community.

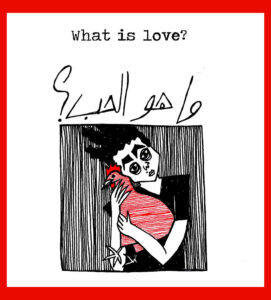

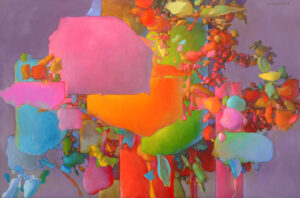

The idea of being united by love is all over the image of the artist. Love here seems to be not just as a feeling, but rather an unveiling of a fundamental unity, and is all over the artist’s photographs, from silver grills stating “I Love You” in Arabic, to figures making heart signs with their hands or wearing glasses frame forming the word “Love” or even veiled faces reminiscent of Magritte kissing.

As Lamrabat articulated in FishEye Magazine, “I was inspired by this idea of a very strong, very romantic love, which we’re used to seeing in American films. But I also remembered my parents, who saw each other for the first time on their wedding day, and who are still very happy together. I wanted to have a bit of fun with the meaning of the expression. Others, too, see two women kissing… In the end, the veil covering the faces is so mysterious that each person draws their own conclusion. And that’s fine! The important thing is love. That simple emotion, that solution to everything. It’s something that speaks to everyone.”

A photographer hailing from the fashion world, Lamrabat’s work stands as an act of resistance and a love letter, a dialogue between Moroccan heritage and global pop culture. At the heart of the photographs from his Homesick series lies a paradox: the longing for a place that no longer exists, or perhaps never existed at all.

It’s a whole imagination that is unleashed here: but not an exoticist one, despite finding cultural tropes in the pictures, but rather an anti-orientalist imaginary, where elements from Western consumerism become decorations, and are integrated into African and Arab cultures.

The photographer even gave a name to this world of his own imagination: Mousganistan, a place in which young people wear clothes that are a blend the iconography of Western capitalism, from McDonald’s golden arches to Nike’s sneakers, with signifiers of Islamic and North African culture such as henna and the niqab.

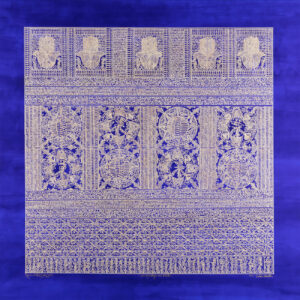

Pictures like “Star-Struck,” for example, presents one of the most recurring symbols in the artist’s oeuvre, the Moroccan star. Here a figure holding onto two stars seems to comment on nationalism an evolving, deeply personal mythology, to which one seems to hold for dear life.

Conversely, a photograph like “Touch the Sky” is more abstract: a figure stands against an expansive blue, draped in an improbable mix of streetwear and traditional garb reflecting the sky, suggesting that heritage is not fixed but fluid, a canvas onto which new identities can be projected.

Lamrabat’s subjects, often faceless or partially obscured, embody the migrant’s condition: visible yet unseen, present yet perpetually elsewhere. In works like Bahibak his recurring Avatar-like figures in blue make gestures that are at once attender and defiant. Despite the glamorous patina, the world where these individuals exist is a utopia beyond a world of cultural divisions. If, like the Skunk Anansie used to sing “Everything is Political,” Lamrabat’s pictures seem to suggest that love, for Lamrabat, is not separate from the political; it is a radical act in itself.

A testimony of this is in the title itself of a recent show of his which took place in 2023 at MAD, Brussels’ fashion and design center, called A(R)MOUR. As the artist revealed in l’Officiel: “The play on words in the title refers to the way in which we protect ourselves, to the garment that can serve as our armor — literally, in fact, when it’s a veil or a hijab — and which also ‘labels’ us, giving us the impression of being part of a group or a community.”

Lamrabat sees his work not as fashion photography per se, but more as photography that happens to have fashion in it. This refusal to be boxed into categories mirrors his larger approach as a Moroccan Muslim immigrant living in Belgium: his approach wants to disrupt exoticist expectations, blurring boundaries between east and west, north and south. Mous Lamrabat seems to be reclaiming imagery in ways that speak to both diaspora experience and African and Arab futurism, an artistic movement that re-imagines science fiction based on traditional cultures from the MENA region and beyond.

A strong ironic and humoristic element is evident in the artist’s work, yet beneath the playfulness lies a sharp critique of consumerism, colonial residue, and cultural homogenization. His use of luxury brand iconography — for example, we see Louis Vuitton patterns on traditional Moroccan textiles, or again McDonald’s logos transformed into talismanic symbols — forces us to reconsider globalization’s impact on identity.

In his figures, often isolated in space, we feel the weight of longing, the push and pull of worlds colliding, the silent but persistent ache of being neither here nor there. Challenging simplistic notions of identity, the lonely models remind us that home is not just a physical place; it is an idea, an emotion, a memory that evolves over time, and even a series of habits sometimes. And this habit can’t help but speak of our families and cultures.

As viewers move through the exhibition, they become active participants in Lamrabat’s world. They witness the contradictions, the loneliness, the heartbreak, and ultimately, the resilience that defines the migrant’s journey. “Until my last breath, I will try to bring people together, having conversations and learning from each other,” says Lamrabat while toasting on the terrace of Loft. “Just to feel love and to show love! And oh man, do we need love in the world we are living in today!”

Ultimately, Homesick is about embracing the contradictions, the beautiful chaos of being in between. It is an incentive to dream, to question, to belong in ways we never thought possible, and perhaps discover that personal world that each one of us carries in ourselves already. And this invitation seems to extend beyond the show, to become an ethos in which the whole Marrakech art scene is deeply invested, as Morocco is increasingly entering the international art conversation.