Although Bīylmawn has recently made a forceful return thanks to its revitalization by Amazigh civil society in the Souss, the highly aestheticized and artistically choreographed innovative reinterpretation of the carnival in the areas south of the High Atlas has not been to everyone’s delight.

Although Bīylmawn has recently made a forceful return thanks to its revitalization by Amazigh civil society in the Souss, the highly aestheticized and artistically choreographed innovative reinterpretation of the carnival in the areas south of the High Atlas has not been to everyone’s delight.

Brahim El Guabli

Bīylmawn festivities this year are mired in even greater controversies than in the previous years. A carnival that has been taking place in several Amazigh-speaking regions of Morocco in the days following Eid al-aḍhā (the Eid of sacrifice), Traditionally celebrated in several Amazigh-speaking regions of Morocco, Bīylmawn is usually observed in the days following Eid al-adha (the Eid of sacrifice). And now, thanks to the Amazigh civil society in the Souss, Bīylmawn has made a forceful return. However, the highly aestheticized and artistically choreographed innovative reinterpretation of Bīylmawn in the areas south of the High Atlas has not been to everyone’s delight. The revelers’ sartorial and makeup choices during the festivities that follow one of the holiest Muslim holidays have elicited criticism from both the “ḥadāthiyyūn” (modernists) and the “muḥafiẓūn” (conservatives). Although on the antipodes of each other politically, these two groups have finally found a common ground in their rejection of Imazighen’s celebration of Bīylmawn.

While reactions of the religious conservatives were entirely déjà vu, the modernists’ positions are pretty shocking. The latter’s tirades against the festival prove that their discourse on modernity and democracy is not abreast of the societal change that is happening in a demographically young country like Morocco, where children and young adults number more than 30% of the population. Moreover, these modernists have clearly not been updated on the strides made globally in the recognition of Indigenous people’s cultural and linguistic rights. Instead of recognizing a celebration that is deeply anchored in Morocco’s Amazigh indigeneity, modernity for these modernists seems to be equated with the eradication of tradition. In its deeper significance, the outright rejection of Bīylmawn is a sign of the ongoing cultural and sociological alienation that has reigned over some Moroccan elites since the French Protectorate in 1912.

Bīylmawn is the fruit of the millennial interaction between the Indigenous Imazighen and their land. Throughout the world, Indigenous people have myths and rituals that bind them to their ancestral lands, and Bīylmawn is not an exception. Anyone who seeks to ban such a carnivalesque observance either speaks from a position of ignorance or even worse from a position of un-Moroccanness. Ignorance can be remedied through learning but un-Moroccanness is a far deeper scourge because it emanates from an inferiority complex that only a long-term process of self-critique and reaffirmation of the foundational significance of Amazighity to all Moroccans’ identity can help overcome.

The current mobilization against Bīylmawn requires a critical reflection on the broader Amazighophobic and anti-art context in which it is unfolding. The negationist responses to the refigured aesthetics of a centuries-old masquerade is in reality a negative harbinger for innovation and creativity in the country. Change is the only constant in the way societies observe their traditions, but the responses to Bīylmawn seem to emerge from an unrealistic yearning to immutable social practices.

Bīylmawn is an example of cultural translation and borrowing that encompass costumes, themes, and gender fluidity, which, taken together, are strengths rather than disadvantages. Bīylmawn’s participants’ ability to enroot their indigenous practice in its local soil while also opening it up to global circulation of symbols, like references in the movie Avatar or the television series The Game of Thrones, has disoriented the proponents of an authenticity that is cut off from the reality of the interconnected world the Amazigh youth live in.

Although not monolithic, anti- Bīylmawn responses to the festival reveal the polarization that exists among urban Moroccan elites. Ahmed Benchemsi, a former journalist, resorted to social media to express his appreciation of the “pagan” tradition. However, not everyone has reacted positively. Unlike Benchemsi, a Moroccan lawyer argued on Twitter (X) that Bīylmawn is “the version of a moribund neocolonial separatism in action under the cover of culture.” Perhaps not knowing that Bīylmawn’s celebration likely predates Islam in Morocco, this lawyer expressed a sort of surprise about the “emergence of unknown pagan rites in the south of Morocco on the occasion of the Islamic celebration of the Eid of sacrifice in the name of the ethnocultural promotion that has been enforced for the last thirty years.” These thoughts would not have warranted a response if the author had not attempted to intentionally link the renewed interest in Bīylmawn to the achievements of the Moroccan Amazigh Cultural Movement (MACM).

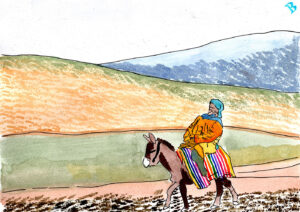

Many Moroccans in Rabat, Casablanca, and Tangier talk about this not-yet-Arabized portion of Morocco in exoticizing terms that situate it outside their intellectual and social geography. In their minds, the Chleuh (Imazighen) live outside time — they are like curiosities from an old treasure chest.

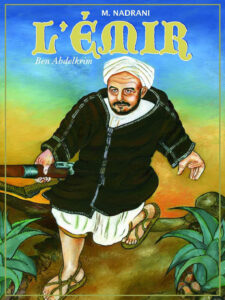

In fact, Bīylmawn has been celebrated in Morocco before the advent of the MACM, and even before the independence of Morocco itself. The proof is that Westermarck conducted his observations about būjlūd (Bīylmawn in Arabic) in 1900, twelve years before the advent of the French protectorate. Beyond the amalgamation, the vocabulary this modernist lawyer used in this tweet borrows, whether intentionally or not, from the lexicon of the French extreme right in its charge against immigration and accusations of racism and Islamophobia leveled at its followers. Without any critical reflection, the French right-wing’s lexical arsenal against what they call Islamo-gauchisme is simply transposed onto Morocco to accuse fun-loving Amazigh youth of ethnocultural separatism. Finally, the insinuation that Bīylmawn is “an unknown rite” reflects the sad reality of most urbanite Moroccans, who know next to nothing about Morocco south of the Atlas Mountains.

The earthquake that hit the High Atlas in September 2023 revealed the divide between two parallel Moroccos: Morocco north of the Atlas and Morocco south of the Atlas. These two Moroccos appear on the same map and are unified by the country’s name, but they are only adjacent to each other, almost neighbors locked in a dynamic in which Morocco north of the Atlas has nothing but disdain for its southern counterpart. The more cared-for Morocco north of the Atlas, which French colonizers called the Maroc utile (useful Morocco) has always looked down on the Morocco of the Chleuh, the Imazighen, who, since the independence of the country in 1956, have been subjected to an Arabizing civilizing mission in lieu of the French mission civilisatrice. Hence, many Moroccans in Rabat, Casablanca, and Tangier talk about this not-yet-Arabized portion of Morocco in exoticizing terms that situate it outside their intellectual and social geography. In their minds, the Chleuh (Imazighen) live outside time — they are like curiosities from an old treasure chest.

This classist dimension is particularly apparent in the recurrence of words, such as primitive and pagan, in different social media commentaries about Bīylmawn. In reality, Bīylmawn is mostly spearheaded by poor and disenfranchised Amazigh youth. It is the celebration of marginal Moroccans who occupy the periphery of the periphery yearlong, which makes the dismissal of their creative reinvention of this festival another disempowering elitist move. One cannot but wonder whether the dismissive elitism of some members of the Moroccan intelligentsia would still be maintained if Bīylmawn were suddenly choreographed by French or American artists à la Halloween. If Bīylmawn were to be called Moroccan Halloween or some other foreign-sounding name, the “modernist” critics of its primitivism would be the first to incorporate it into their exclusive practices without heeding its satanic or pagan rituals. For instance, Gnawa music, which has many pagan elements, has been resuscitated from oblivion, and the Amazigh identity of Taṣṣurt (Essaouira) has been entirely assimilated to this musical genre. The difference between Bīylmawn and Gnawa is that the latter was made trendy by Hassan Hakmoun and high caliber stars, like Randy Weston, Richard Horowitz and others, while the former has remained the product of local artists.

The religious institution is the other heavyweight that intervened in this debate. Like all the countries that fell prey to petrodollar Wahhabism and its literalist Islam, Morocco has, in the last thirty years, seen a major transformation of religious practices as a result of Wahhabism’s influence. Growing up in a small village in the south of Morocco, I was lucky, like my generation, to be socialized into the organic Moroccan Islam, which reconciled pre-Islamic beliefs with Islamic learning and rituals. Our education in school didn’t prevent us from returning to the mosque to memorize the Quran during the breaks. Secular and religious education went hand in hand with participation in ancestral traditions of saint worship, lmāruf (couscous offering for a saint), and rituals of anzār, whereby women and children walked for a couple miles to the village dam to invite the rain right before the end of summer. Even the imam participated in some of these rituals, embodying a healthy relationship between the mosque and society’s beliefs.

In the 1990s, however, the winds of change blew over these traditions, which gradually vanished as a result of Wahhabism’s rejection of what they considered shirk (association of other creatures with God). The recent opinion of the president of the Council of Moroccan ‘Ulama in Skhirat and Témara against Bīylmawn is the culmination of this Wahhabization. According to this jurist, who proudly claims his Amazighity, some aspects of Bīylmawn are haram and un-Islamic. Morocco is a very moderate country where jurists cannot give fatwa willy-nilly. This choice strengthened the country’s spiritual security and placed the authority of religious regulation in the hands of the state. It is dangerous when individual religious scholars edict fatwas to regulate social behaviors outside the purview of the law, like what happened when a YouTube celebrity attacked Amazigh music icons Fatima Tabaamrant and Ahmed Outaleb. The last thing Moroccans need is the emergence of a hisba system — like the one that terrorized Egyptian intellectuals for many years — to infringe upon their fundamental freedoms.

Amazigh activists have not remained silent vis-à-vis these attacks. Lawyer Ahmed Arhmouch wondered if this official jurist’s statements conveyed the position of the Ministry of Endowments and Islamic Affairs. Most important, however, is Arhmouch’s rejection of the “cheapening of aesthetic and artistic manifestations of Amazigh ancient civilization in order to cleanse the Amazigh landscape of the manifestations of its cultural richness.” Scholar Mohamed Benidir asked whether there are “any religious rituals that are not embedded in pagan roots” to further complicate the question of paganism. Civil society activist Mohammed Jaouhari went even further by distinguishing between “divine Islam,” which condones Bīylmawn, and “political Islam,” which rejects it. Jaouhari also emphasized the masquerade’s theatrical aspect, which allows the participants to “communicate their messages to their families, institutions, and communities.”

Amazigh activist Dr. Abdellah Sabri also refuted Bīylmawn’s opponents’ argument against the festival. He lamented ignorance of the basics of “cultural production” by those who contest the reinvention of Bīylmawn, underscoring along the way the similarities between this discourse and the dismissal of music, art, and theater as futile activities. His was a warning against the risks that will emanate from subduing artistic creativity to religion. Indeed, the reactions to Bīylmawn’s innovative aesthetics indicate the threat this imported religiosity could pose to the earthly happiness of the already-impoverished Moroccans of the periphery who find both joy and solace in these festivities.

The author of the magisterial study of the celebration of Bīylmawn in postcolonial Morocco, Abdellah Hammoudi, called Bīylmawn “street theater” based on his observation of public performances. Hammoudi commented that “the events in the street gave rise to the hypothesis of a preparation time and action ‘offstage.’ Above all, in reality the scenes are sketched out, begun over and over again, aborted, then replayed in an atmosphere of freedom and relative disorder that “Hammoudi’s observations contain several insights that tell us three important things about Bīylmawn. First, the dialectic between constant and changing aspects of the performance. Second, the performances are both curated and scripted before being staged in public. Third, freedom is Bīylmawn’s condition of possibility, and all religious and social inhibitions are bracketed for the duration of the performance.

Part of the controversy has been focused on Bīylmawn’s adaptation to its contemporary performer and audiences needs. However, Hammoudi’s insights contain an indication that change is the celebration’s lifeblood and its future sustainability. Older generations did not innovate as much because they lacked both material and educational resources. Therefore, the hides were not elaborate, and soot was used to color Bīylmawn’s face. The new generations of Imazighen live in a different world, in which both resources are abundant and global connections are easily made. Their choreography and aesthetics for Bīylmawn’s new iterations are a testament to the celebration’s adaptability and its openness to innovation. For instance, Rachid Bihrmach, one of the Bīylmawn stars, shared the meaning of his mask, which features Agurzil or the Amazigh God of war, on Facebook, revealing the significance of its transnational story.

Historically men played the roles of both men and women during the performance. According to Westermarck, “[a]man is dressed up in the skins of some sacrificed goat or sheep, and another man or boy is disguised as a woman. Sometimes they are regarded as husband and wife, and sometimes the woman is regarded as the wife of a third person, an old man.” However, the elaborate makeup used by the youth nowadays has raised questions about gender fluidity, particularly because the costumes and the elaborate makeup blur the distinction between men and women. Much of the unsaid in the criticism of the festivities is laden with anxiety over gender ambiguity and androgynous costumes, which push paranoid conservatives to see homosexual and transgender identities all over Bīylmawn’s cartography. Accordingly, some vehement reactions against Bīylmawn are rooted in homophobia or in a binary perception of the world. This is, of course, further exacerbated by the visibility of characters inspired by Hollywood movies, which further unsettle the sensitivity of those who crave an archaic performance even at the risk of not resonating with the younger audiences.

Hammoudi’s prescient description of Bīylmawn as “street theater” has been borne out by the emergence of the carnivalesque orientation of its recent iterations. Bakhtin has theorized the forms of inversion of religious and political authority even as laughter remains the carnival’s primary goal. The burlesque, the grotesque, and the silly things that accompany Bīylmawn only make sense when they are perceived in their fundamental quality as role playing within a reinvented tradition. This is not unfamiliar to Imazighen. In fact, tanḍḍāmt (the spontaneous poetic jousts between several poems) is one of the live Amazigh art forms in which this role playing is embodied. As very respected people in their communities, the poets take on roles during the performance, such playing devil’s advocate or affronting a rivalry. However, when the performance ends, everyone returns to the “real” world, and everything that took place during the performance is subsumed under the term lhdert (entertainment or fun-making). The recognition of Bīylmawn’s theatrical dimension may dissipate much of the angst it has elicited from its opponents.

It would be superficial, nonetheless, to merely consider the backlash against Bīylmawn as an attack on the festival alone. In reality, these reactions take issue with an indigenous Amazigh cultural practice that is dear to Moroccan Imazighen south of the High Atlas. Bīylmawn has already disappeared from the Riff and several other areas, but the current endeavors to eradicate its celebration in the places where it is still an essential part of Eid festivities should be resisted. If Amazighophobic forces manage to take away the indigenous practices that anchor Imazighen in both place and time, Imazighen’s very existence in their homeland could be at stake in the near future.

Is it now proven by Genetic tests – now very popular – that there are NO Arabs in North Africa (Tamazgha), apart from Arabized Imazighen who still believe in such myths created by… the French colonial administration. This phenomenon of rejecting its own roots is called ‘Alienation’.