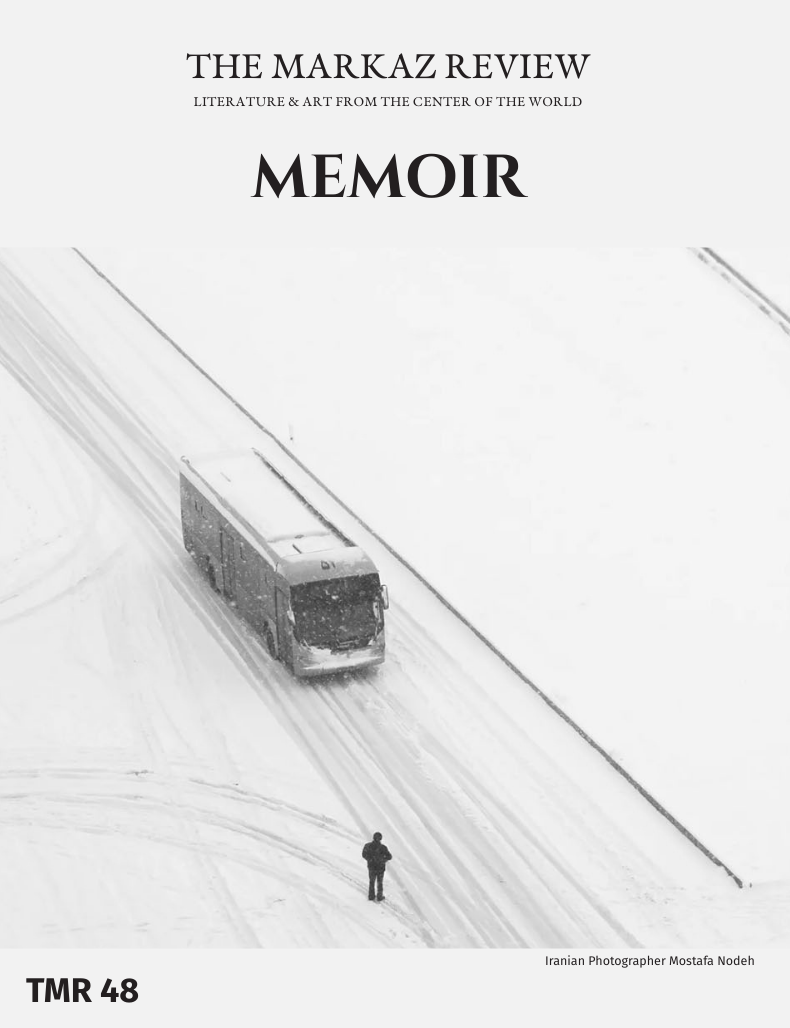

What do we choose to remember, and what do we choose to forget? A special monthly issue devoted to the genre of memoir...

In TMR 48 • MEMOIR we present several original essays, two short stories and two book reviews, designed to convey the immediacy of memory, as both an element of storytelling and the basis for history.

In medieval Arabia, a tradition of biographical entries by religious scholars emerged to prove or disprove direct lineage to the Prophet Mohammad. Among these entries were vivid instances of the first known autobiographic accounts from the Islamic world. Self-discovery as opposed to a recording of an entire life is a defining characteristic that distinguishes memoir from autobiography. Memoir, a noun, has its roots in the 15th-century French memoire (“note or memorandum, something to be kept in the mind”) and the Latin memoria (“to remember”). Despite the prominence of Arabic, as the lingua franca of the Islamic world for 1400 years, early political and religious memories were written in the languages of the Ottoman and Persian empires.

The first memoir by an Arab woman was published in German. Zambian princess Sayyida Salme bint Said, later known as Emily Ruete, 1844–1924, wrote Memoiren einer Arabischen Prinzessin aus Sansibar. Nubar Nubarian Pasha (1825–1889), an Armenian fluent in Turkish and educated in France, rose to become the first prime minister of British controlled Egypt. He wrote his memoirs in French. Meanwhile, in 19th century antebellum US and the West Indies, African slaves urged to write their memoirs by abolitionists for anti-slavery campaigns wrote memoirs in Arabic.

By the mid-20th century, the independence movement across the Middle East spurred first person accounts by Taha Hussein, Sonallah Ibrahim, Assia Djebar, Latifa al-Zayyat, Mahmoud Darwish, Mourid Barghouti, Edward Said, Haifa Zangana, and Radwa Ashour, and is written about in Tahia Abdel Nasser’s book Literary Autobiography and Arab National Struggles (2019).

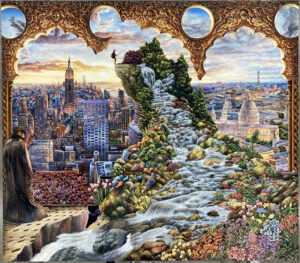

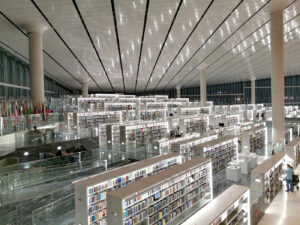

Memoirs not only recount the individual’s journey but also enrich our grasp of shared history, illustrating how personal lives are interwoven with the larger tapestry of societal change. This interplay between personal narrative and historical context ultimately raises questions about memory, truth, and the ways we construct our understanding of the past. In this vein, Todd Reisz reviews two new histories of the Persian Gulf — that challenge often-told narratives of the channelling of sudden petroleum wealth into visible, even spectacular, infrastructural development over the past 80 years, allowing readers to see the Persian Gulf as a connecting point rather than a delimited void. Malu Halasa reviews Memories of Palestine through Contemporary Media (2024), a psycho-social-virtual memoir of Palestine of both emotional and geographic proportions in which she finds that “Palestine transits timelines and exists simultaneously in the past, present, and a possible future.” And in her essay “Flight Plans: From Gaza to Singapore,” Chin Chin Yap writes how imperial air routes from European capitals to their Asian colonies once connected Gaza and Singapore, how under occupation, Palestinians have repeatedly been denied their own civil aviation; this symbol of freedom, modernity, and statehood that is deeply connected to their quest for sovereignty.

In any memoir, the journey back home transforms into more than just a physical trip; it evolves into an emotional odyssey — one that unearths the threads that bind us to our past and shape our future. Ultimately, it’s a celebration of resilience, love, and the timeless connection we have to the places and people that define us. In her essay, “Chronicles of a Boy Manqué,” Rana Haddad recalls her girlhood between Syria where she grew up a “Boy Hassan” in Latakia, refusing to wear a dress and act like a lady, bucking the conventions of her day, and England where she moved with her family when she was fifteen and dressing up as a tomboy began to cause her “untold social distress.” She writes: “At fancy dress parties I dressed up as a clown in a suit, baggy trousers, a red nose and a large blonde wig. I wanted to hide my girlness and find an excuse to wear a suit and smoke a pipe. I didn’t want to be Simone de Beauvoir, I wanted to be Sartre. I wanted to be the First Sex, the protagonist, the subject of a story, or a life, not the object.”

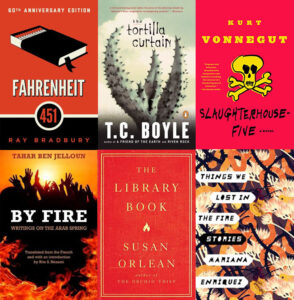

In January, the fires of southern California, wild and manmade, ravaged the southland as never before, creating thousands of new homeless refugees and billions in property damage. Many of our friends — musicians, writers, artists, filmmakers et alia — lost their homes. Our contributing editor Francisco Letelier has been here before, and in “Ravaged by Fire” connects the devastation of climate change with the decimation of Gaza, and other disasters over time.

In fiction, The Markaz Review is delighted to publish Baxtyar Hamasur, a Kurdish short story writer born in Slemani. His story “A Strand of Hair Shaped Like the Letter J,” translated for TMR by Jiyar Homer and Hannah Fox, is the only one of his works to make its debut in English. And Dia Barghouti’s short story about a Palestinian woman invited to a wedding who wants to leave her house and return, but only if she can be certain of the return, “as colonialists are terribly unpredictable.”

As Syria marks two months of freedom, a significant number of Syrians living in exile are returning home. After being away for 13 years, writer and translator Odai Al Zoubi reflects on his first trip back to Syria in his essay “The Closed Door,” translated from the Arabic by TMR’s managing editor, Rana Asfour. Al Zoubi finds himself revisiting the Hanging Mosque, the Barada River and everything in between, where he reconnects with a sense of lost time and place, where “rural families flock to hotels and the relatives of missing persons from both Assad regimes come together in grief, seeking answers to questions that may remain forever unanswered.”

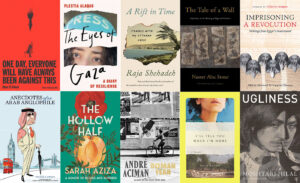

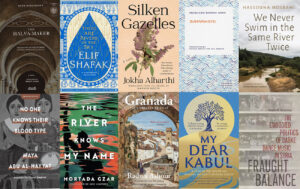

Finally, Farah Ahamed in “What Remains: Voice and the Poetry of Forugh Farrokhzad,” remembers what it was like to lose her voice as a result of personal tragedy. To round out the MEMOIR issue, Rana Asfour has put together a list of 10 new recommended memoirs set to hit the shelves in 2025.

In the age of narcissism, we wonder, has memoir taken on new forms? Are personal, heartfelt narratives always reliable? What is the story of your life — or a single episode that you have come to consider a milestone, a defining point that you look back on with introspection? How does one recount a life in just a few thousand words?

Happy reading.