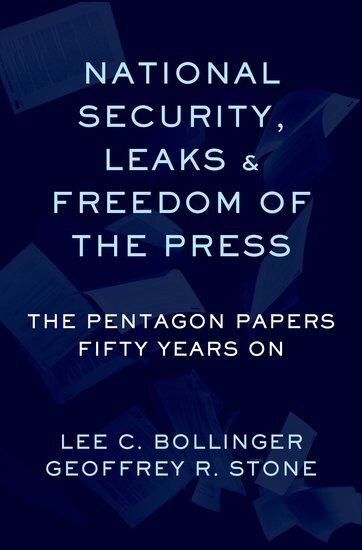

National Security, Leaks and Freedom of the Press: The Pentagon Papers Fifty Years On

Edited by Geoffrey R. Stone and Lee C. Bollinger

Oxford University Press (April 2021)

ISBN: 9780197519387

Stephen Rohde

One could argue that the United States is not a democracy in which personal privacy enjoys broad protection and the government largely functions in the open. Quite the opposite. Increasingly, private individuals and organizations are subject to unprecedented surveillance and invasions of privacy, while the government is able to operate behind a heavy cloak of secrecy, protected by a thicket of laws, regulations, court rulings, policies, and norms that undermine and criminalize efforts to expose official wrongdoing, illegality, mendacity and corruption.

The American public deserves to know what its government is doing so the people can fulfill the ideals of self-government. And the truth has never been more important, especially at a time when a President of the United States can lie to the people more than 30,000 times.

This hyper-secrecy is notably prevalent in the area of national security, where there is an epidemic of over-classification of vital information by the government. And this unwarranted government secrecy sets the stage for leaks and whistleblowing, which in recent years has resulted in an unprecedented number of criminal prosecutions, including, most famously, Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, and Julian Assange.

Fifty years ago, in 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court, in the famous Pentagon Papers case, rejected an attempt by the Nixon administration to enjoin the New York Times and the Washington Post from publishing excerpts of a classified, seven-thousand-page report recounting the history of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War that had been leaked by Daniel Ellsberg, a government employee working for the Defense Department. The majority, in a 6-3 vote, held that a prior restraint on freedom of expression—restraining speech before it is even published—was presumptively unconstitutional and that Nixon’s Department of Justice had failed to carry its burden of proof to present sufficient evidence of harm to national security to overcome that presumption.

The Pentagon Papers decision was a significant First Amendment victory. What are often overlooked, however, are aspects of the ruling that continue to pose serious threats to freedom of the press. Under the law, a prior restraint can still be upheld if the government presents evidence of extraordinary circumstances which five members of the Court deem sufficient to overcome the presumption. Such a ruling is now more likely than ever given the super-majority of six conservatives on the Court.

In addition, the Pentagon Papers decision affords no protection for the leakers who make unauthorized disclosures. In fact, Ellsberg himself was criminally prosecuted until the charges were dismissed due to prosecutorial misconduct. Because the Times and the Post had not solicited the leaked materials or participated in Ellsberg’s acquisition and copying, the Court did not decide—and has yet to decide—whether the press possesses a right to elicit classified information or assist potential leakers in obtaining and transferring such material to the media. This is indeed a central issue in the Assange prosecution. And it may come as a surprise that the Court has never recognized a general constitutional right of the public to have access to information in the hands of the government.

The Pentagon Papers decision left in place these and other troubling questions, which the Court has not answered to this day. To address those critical questions, Lee Bollinger, President of Columbia University, and Geoffrey Stone, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, have gathered a wide array of essays from two dozen leading thinkers in their intriguing new book National Security, Leaks, and Freedom of the Press: The Pentagon Papers Fifty Years On. This comprehensive volume sets out to explore “one of the most vexing and perennial questions facing any democracy,” namely, “how to balance the government’s legitimate need to conduct its operations — especially those related to protecting national security — with the public’s right and responsibility to know what its government is doing.”

At a 2016 hearing before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, Chairperson Jason Chaffetz (R. Utah) noted that 50 to 90 percent of classified material is not correctly designated. Nearly a decade earlier, former US diplomat George Kennan likewise observed that “upwards of 95%” of information about foreign governments is available from open sources but nevertheless is classified by the US government. In their essay in National Security, Leaks, and Freedom of the Press, Keith B. Alexander, former Director of the National Security Agency, and Jamil N. Jaffer, Founder and Executive Director of the National Security Institute and Professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, concede that 50 to 90 percent of classified information is “mislabeled” and that “much information could be declassified with fairly limited, if any, harm to national security.”

“50 to 90 percent of classified material is not correctly designated.”

— Jason Chaffetz

As Avril Haines, former White House Deputy National Security Advisor, writes, due to over-classification and excessive secrecy, our current Supreme Court framework “bizarrely” depends “on government employees, contractors, or others to break the law and, where relevant, the terms they have agreed to in the course of their employment, in order to disclose information that many of the Justices indicated was precisely what the Founders would have wanted to see published under the First Amendment—information exposing controversial government action essential for the public to know in order to hold the government accountable, as our political system envisions.”

Haines adds that “with an increasingly powerful executive branch, a weak Congress, and the likely continued use of US military force abroad, it seems clear that the need has never been greater for a framework that promotes the disclosure of classified information when it is important to an informed public debate, as the public may be the only effective restraint on executive policy and power in this realm.”

Yet while the worthy essayists in this timely book—and the rest of us—sit back and comfortably debate the development of a new “framework” that promotes an enlightened citizenry instead of pervasive secrecy and concealment, a handful of brave individuals have placed truth-telling above their own personal liberty. In March 2013, Edward Snowden, having worked as a system administrator and infrastructure analyst for the CIA, Dell, and Booz Allen Hamilton, under contract to the National Security Agency, reached his breaking point as he watched Director of National Intelligence James Clapper lie under oath to Congress. Snowden has since stated in testimony to the European Parliament and in numerous interviews that he had expressed his concerns about NSA domestic spying to at least ten officials, all of whom told him to stay silent. Consequently, in June 2013, he revealed thousands of classified NSA documents to journalist Glenn Greenwald and others, leading to startling news stories in The Guardian, the Washington Post, and other publications. On June 21, 2013, the Obama Department of Justice unsealed an indictment against Snowden on two counts of violating the Espionage Act of 1917 and theft of government property. Snowden secured asylum in Moscow and was granted permanent residency in October 2020.

As reported by the Washington Post, Snowden’s disclosures revealed for the first time that the “National Security Agency and the FBI are tapping directly into the central servers of nine leading US Internet companies, extracting audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track foreign targets.”

Snowden has been labeled both a traitor and a hero, but either way, several essays in National Security, Leaks, and Freedom of the Press credit him with prompting “an important and democracy-enhancing debate,” as noted by Lisa O. Monaco, former Homeland Security and Counterterrorism Advisor and currently Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Reiss Center on Law and Security at New York University. In the wake of Snowden’s revelations about NSA spying, President Obama terminated surveillance under controversial Section 215 of the USA Patriot Act and established a new Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board. The USA Freedom Act of 2015 was enacted and the government declassified more than forty previously secret opinions and orders of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court. But while the Post and the Guardian shared the prestigious Pulitzer Prize for public service in 2014 for reporting based on the material Snowden disclosed, Snowden has received no such honors. Instead, he has been indicted and remains living in exile in Moscow.

Much the same is true of Manning and Assange. Chelsea Manning was sentenced to 35 years in prison (commuted to 7 years time-served by President Obama) for disclosing evidence of US war crimes to WikiLeaks. Today, Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks, is sitting in a British jail, facing up to 175 years in prison if convicted under the Espionage Act, while the Times, the Post, the Guardian, and news outlets around the world published ground-breaking stories based on the information revealed by WikiLeaks. Assange’s prosecution is unprecedented; it is the first time a publisher has been charged for revealing classified information. The Obama administration declined to prosecute him, citing “the New York Times Problem:” How can you justify indicting Assange if you don’t indict mainstream media that routinely publishes leaked classified information?

The problem is not limited to these particular cases. According to the essay by Stephen J. Adler, Editor-in-Chief of Reuters, and Bruce D. Brown, Executive Director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, in the last ten years, “the government has brought eighteen cases against journalistic sources and an additional two based on the public disclosure of classified information outside of the news media context.”

In 1974, Hannah Arendt warned us that “if everybody always lies to you the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer….And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.”

Widespread government secrecy, alongside the punishment of truth-tellers, betrays fundamental principles underlying our democracy. The Supreme Court has repeatedly declared that the First Amendment reflects “a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” in order to provide “free political discussion to the end that the government may be responsive to the will of the people.” Secrecy and lies deprive the people of the capacity to think, to judge, and to thrive in a free and open democracy.