Bil’in, a village in the occupied West Bank of Palestine, is known for its creative resistance against the Israeli separation barrier that zigzags into occupied Palestinian territory. For 15 years it has been documented through articles, radio stories and documentaries. Five Broken Cameras, a documentary film that attests to the struggle of Bil’in, earned its directors, Palestinian Emad Burnat and Israeli Guy Davidi, an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary. Bil’in remains on the forefront of anti-Occupation activism.

Francisco Letelier

I am invited to join a delegation of artists that will travel to Bil’in by Hector Aristizabal, a Colombian theatre artist and pioneering psychologist who survived civil war, arrest and torture in Medellin.

I anticipate that it may get complicated, for we will be creating an arts residency amidst weekly protests that have resulted in countless injuries and the deaths of two protesters.

I arrive in Israel wearing a crucifix and when interviewed at the airport about the purpose of my visit, I show excitement about visiting the Holy Land. A life-long friend, stationed in Jerusalem at the time, gives me a place to land. Other participants do not have an easy entrance, and are detained and questioned for hours.

The next day, getting out of the Holy City and into the West Bank is complicated and nerve-wracking. Living under occupation is a permanent state of siege; soldiers and guns are everywhere. After navigating checkpoints and blockades, the taxi I have taken with other delegates makes its way down into the village. The setting is post-apocalyptic. The surrounding barrier wall that keeps Palestinians from entering present day Israel appears in our sights. It defies exaggerated expectations; topped with concertina wire, the barrier has made possible the annexation of 600 acres — over 50% of the land belonging to the village.

Bil’in is clearly an open-air prison. Nothing prepares first-time visitors for the act of violence that is the wall. The spire of the mosque rises in the shimmering heat. Beyond the village, on the other side of the barrier, glittering with modernity, the Israeli settlement of Modi’in Illit, sits on land taken from five villages — Nil’in, Kharbata, Saffa, Dir Qadis and Bil’in. We arrive for the annual olive harvest, yet half the groves and centuries-old trees now lie beyond the wall.

My work as a public visual artist stresses collective action and participatory activity, while for many years Hector Aristizabal has been using Theater of the Oppressed and other methodologies to collaborate with a global community of organizers, educators, therapists and activists engaging social problems, activating communities, and experimenting with new social and political possibilities. Hector has been to Palestine before, working with the Freedom Theatre based in Jenin Refugee Camp. The Freedom Theatre stresses popular culture through art for social change and cultural resistance, empowering people of all ages to express themselves through art.

I want to help create participatory murals and to get as many people as possible involved.

Murals created in this way are more like a barn raising, a quilting circle, a milpa, or an olive harvest, rather than what most people imagine comprises an artistic enterprise. The context and intentions of popular culture can become elusive when most everything we see and hear concerning ‘art’ reinforces hegemonic ideas about fame and talent. The cult of individual genius is alive and well.

As a result, collectivity is rarely an art world darling, no matter how revolutionary the idea conveyed. The art world is more than capable of co-opting and commodifying ideas, gestures, objects and clever graffiti and almost always does. It’s difficult, however, to exploit forms that belong to no one and can best be accessed through participation. It’s easy to forget that art is not only a pageant of spectacle for spectators; it can also be a process of experiences that authentically build powerful human connection.

The Popular Struggle Committee of Bil’in wants murals that chronicle their heroic struggle, but a narrative mural that tells a story of a people can’t be made quickly, and can take years or a lifetime. It can be hard to convince a room full of people that they themselves can come up with important, problem-solving expressions of thinking, imagination and creative expression.

Our mural team is comprised of individuals that live in the village, a few international delegates and 10 students from The International Academy of Art in Ramallah. There are obvious differences between all of us, but surprisingly, the distances between some art students and villagers, all Palestinians living in the West Bank, are the most challenging.

The student artists, like young people in most places, are attached to cell phones and social media. They are from city families, wear nice clothes, speak some English and lead secular lives. A few are not clearly enrolled in either the political direction of our Host committee, or in the task of creating art with people and for people. Each student wants to make their own mural, an assignment apparently given to them by their teachers at the Academy. One of the senior students from the group, Alaa Ababa, has painted several murals in Ramallah; his experience and leadership will hold our group together. Emma Elliot Walker, a Scottish fellow artist on our delegation, possesses social and communicative tools and solid artistic skills.

Some of the Ramallah students confide they do not believe the protests in Bil’in are effective. Over the next few days, through their close contact with the people in the village and the group of international delegates, these ideas will undergo a shift.

We work as a team on an initial simple design of olive branches on a wall along the main road. By the end of the first day, we have completed a 60-foot stretch of wall and our group of strangers is coalescing into a team. The stylized branches we paint are not masterpieces but they have an immediate visual impact. We decide to paint as many walls as we can and I agree to help them with their individual designs and ideas. We have limited supplies; mixing pigments into white paint we obtain some brighter colors, but we are mostly limited to black and white.

It’s impossible to paint on the actual barrier around Bil’in. The Israeli Defense Forces patrol the wall, and those who approach through the olive groves are repelled with force. Our delegation is briefed on the weapons and projectiles we might encounter as we prepare to join villagers and supporters who arrive from many locations to join in the weekly Friday protest.

The goal of the weekly march and protest is to reach the wall, but long before we reach it, patrol vehicles swarm out from the wall and we are encircled. Our delegation stays back from the front lines — our role is to work with those who live in Bil’in, not to confront the Israeli forces. Although these protests are often described as peaceful and nonviolent, young men with slings and face coverings make their way to the front of the column, while locals and our delegation take up the middle, and other visitors fall safely behind, hoping for photo opportunities. Yet the geography and placement of troops allow tear gas canisters to reach the whole column of marchers; young men, mothers and children, religious and civil leaders, artists and protest tourists are eventually all engulfed in noxious fumes.

We assumed there would be a retreat, but are now surrounded inside a geographic bowl. A brother and sister from Bil’in have already lost their lives navigating the winds and gas from this spot in order to approach the wall. Both were shot in the chest with tear gas canisters; at close range they are projectile weapons. At least 18 more have been killed protesting the wall in surrounding villages and towns.

During our initial workshops with the Bil’in community, some art students are unimpressed with ideas from village community members. They are disappointed that people want to only paint barrier walls, demonstrations, and offer up ideas that to the students seem like clichés. My collaborators from Ramallah have never made this kind of community-based art, and they are finding themselves not only within the social divisions that exist between those who live in the city and those who live in Bil’in, but also between those who call themselves artists and all others. For the first two days we brainstorm and make drawings, there is little direction, and I trust the process as we develop individual and group ideas.

One morning, as the rising sun warms the white walls along the main road, we paint monumental thistles. We are a vibrant mix of collaborators, men, women and children of all ages. I am wearing work clothes, the women from the village however, are impeccably dressed with long skirts and head coverings. Each manages to work without dripping paint on her clothes. As the images appear on the walls, cars slow down and there is the constant drone of horns. Later a local tells me the thistle is used in the Jordan River Valley as a symbol of resistance to the occupation. He shows me a leaflet with an image of a thistle with the slogan, “To exist is to resist.” Yet many are not familiar with its symbolic use and when an older man on a white donkey ambles by, he engages me in conversation. “What is meaning?” he asks in broken but plain English. I point at the plant and pantomime kicking it and digging it up and make gestures that show it comes back, blooms again. He nods his head, yes, yes.

“Even fire, always life. Thank you.”

The plant is virulent and fire-resistant; it has lovely thorns and needs little water. On the wall we write the word PERSIST.

In the rugged hills and lands surrounding Bil’in, the flower heads of the stout prickly thistle known in Arabic as ‘Akkub or Gundelia are reputed to be a delicacy, a cross between asparagus and artichoke worth the trouble of gathering and preparation.

The tale of the ‘Akkub (Hathi haddoutet el ‘Akkub):

Found east of the Mediterranean, the perennial ‘Akkoub (عكوب) in Arabic is called silifa in Greek, Akuvit ha-Galgal (עַכּוּבִית הַגַּלְגַּל) in Hebrew, Kangar (կանկառ) in Armenian and Persian (كنگر), Kenger in Turkish and Kereng in Kurdish.

(collected by the Center of Folktales and Folklore in Haifa, Israel):

There was once a merchant who was traveling through the wilderness with a stranger, and he murdered the stranger for the sake of his riches. As the wounded man fell he grasped at an ‘Akkub plant that grew by his hand and cried out with his last breath, “This ‘Akkub is my witness that you have murdered me.”

But the merchant thought nothing of it and went away with the stranger’s possessions.

Years passed and he traveled again through the wilderness and passed that place this time with his friend and partner. The ‘Akkub was dead and dry and was whirling about, dancing in the wind. The merchant smiled as he saw it and his friend said, “Why do you smile?”

At first he would not say why, but the friend compelled him. Then he said, “I smile, because here I once slew a stranger, and before he died he cried, ‘This ‘Akkub is my witness that you killed me,’ and now the ‘Akkub is dead and dances in the wind.”

More years passed and one day the merchant quarreled with his friend and struck him. The friend in anger cried out, “Will you slay me as you slew the stranger?” so loud that the neighbors heard. An inquiry was made and at last the merchant was brought to justice. The ‘Akkub was indeed the witness.

This story is used proverbially to this day. Villagers will say “The ‘Akkub is the witness.”

At a crossroads, based on drawings created by a village participant, we paint a stylized representation of Jerusalem surrounded by little houses. It is a sacred city to those who live in Bil’in, but they are not allowed to travel there. We paint hundreds of small houses on the white walls that surround the road, representing those who cannot travel, have no passports and live in the shadow of walls. Homeowners come out to the street, coffee is shared, while children and others join in.

Up the road I help another team paint large, stylized keys representing the homes left behind during the 1948 Palestinian catastrophe and exodus, or Nakba. As we progress, the walls and streets of the village come to life with crews of painters and symbols of resistance and memory.

The owner of the main store in town lets us know he would like us to paint his walls. A team of young men arrives to help, as we clear knee-high piles of plastic and trash before we begin. We devise a method to scrape the rough walls and then paint silhouettes of people flying kites that turn into birds flying past the barrier wall. It’s a powerful day of camaraderie, collaboration and understanding. The wall can be seen from a great distance. Those who drive, walk or ride into town feel the impact of the painted walls.

I wake up to the grainy amplified sounds of the adhan — the muezzin’s first call (fajr) to prayer

at first light — and work until the sun’s light turns golden. The essential tasks of painting walls are not glamorous. I wash brushes, mix paint, and carry heavy buckets of water up and down the long hill that goes into the center of town. I put paintbrushes and paint into people’s hands. I sense that our group is beginning to understand that we are creating monuments to cultural memory. Our understandings are greater than our works of art. As often is the case with people-centered and community-driven culture, our work is like an iceberg, only partially seen. The simple murals lining the walls of the village, cannot be fully appreciated without knowing the human interactions and understandings that have gone into their creation.

We are housed in the Bil’in Sports and Youth Club, funded through the Republic of Germany and UN Development Program for Palestine. Late at night, ten days into the residency, we hear explosions. The doors and shutters are bolted tight, as we hear vehicles and the sounds of people shouting.

A series of stun grenades hits our building, shot by Israeli troops from the street gate.

Also known as flash grenades, flashbang, thunderflash or sound bombs, they are a less-lethal explosive device used to disorient an enemy’s senses. They emit a blinding flash of light of around 7 megacandela and an intensely loud BANG of greater than 170 decibels.

The flash activates photoreceptor cells in the eye, blinding it for five seconds. Afterward, victims perceive an afterimage that continues to impair their vision. The volume of the detonation also causes temporary deafness and disturbs the fluid in the ear, causing ringing and a loss of balance. The concussive blast has the ability to cause other injuries, and the heat may ignite flammable materials.

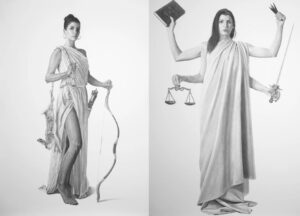

We based this mural on the work of Mustafa al-Hallaj (1938-2003) who was a Palestinian artist, a pioneer of Arab contemporary art, and a true icon when it comes to graphic arts in general. After the 1948 war, Hallaj’s family moved to Damascus, and he spent most of his life in between Syria and Lebanon. He lost 25,000 of his prints in Israeli attacks on Beirut during the 1982 Lebanon war but managed to save the wood and masonry cuts he used to make them. In 2003, Al-Hallaj successfully rescued his famous work “Self-portrait as Man, God, the Devil” from an electrical fire in his home studio, but died after running in to save other works. He was buried in Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus.

As I lie on a foam mattress on the tiled floor, I hear the explosions and yells of delegates who are sleeping on the roof. The smell and effects of tear gas waft through the building. After the soldiers depart, we cautiously go out to the street and learn that they are looking for a young boy. The soldiers can’t find him and so they arrived to take another boy, known to be his friend, into custody. That boy lives just next door to where our delegation is housed. The family resists the soldiers, the teargas and stun grenades and physically yank the boy away from the squad of soldiers. Just 24 hours later, in the neighboring village of Beit Laqiya, 13-year-old, Bahaa Samir Badir is shot in the chest and killed, in a similar raid by the IDF.

We care for ourselves and other members of our delegation. Many experience the shattering of pre-conceived notions concerning legal structures, safety, and human rights. Some have stepped off the edge of their known world, into a place where arbitrary violence is not only possible but actual fact. Becoming witness is an intense and transformational process.

We find ourselves among survivors. In other places the survivor is urged to “heal” from experience, but here healing has a different face. The survivor must continue to elude danger, continue to survive in the face of persistent threat. In other places “healing” is connected to forgetting, trauma is something that must be massaged and meditated away, allowed to scar, best not triggered, transformed into something else. Here, forgetting is not an option, quick wits and body memory, knowledge of the wind and the actions of authority allow survival to continue. No one gets away.

During our initial workshops with the women of Bil’in, we are in unfamiliar territory when I (a foreigner and stranger) pose questions about daily life. I reveal details of my own personal history, about experiencing the loss of loved ones through state violence, visits to concentration camps and working in prisons. In this way we create a place of safety where women and others talk about incarcerated children and men, violence, fear and hope.

The lives of the people in the village are similar to the lives I have known since I was a child, as are the conditions of threat and the responses to violence. When at work on the street I feel at home.

The manner in which we incorporate others and create conversations, dialogues and collaborations makes it possible for people to trust what we are doing. People take ownership of both the process and the outcome.

We travel as a delegation to a neighboring town where Hector, residency participants and Bil’in residents will perform a work of forum theater. The town is in ruins and we hear the sounds of gunfire and explosions from a nearby Israeli firing range. This kind of theater asks for audience participation and there are several people from the town on stage when gunfire erupts from the street and we are engulfed in tear gas. Armed soldiers enter the courtyard of the UN-designated building where we are congregated, claiming a child has thrown rocks at a passing convoy. They pass through the crowd pointing their weapons, and then leave abruptly.

On the following Friday, our delegation has made huge props and puppets for the demonstration that coincides with the annual olive harvest. We have taken a break from painting and visited groves to help with the harvest and participated in adding the last touches to crowns and placards that we will wear and carry to celebrate harvest during the Friday protests.

There are many more of us gathered than in the previous week. It’s a predictable script. Departing from the center of town towards the wall, we are met by IDF jeeps on the route. While other vehicles take strategic positions, a hail of tear gas ensues, but winds are favorable and blow the fumes mostly away from us. Emboldened by the weather, we continue our route. I count a dozen or more plumes of gas, causing many marchers to fall behind. As I lend a hand carrying a huge cardboard tree, I look over to the other side of the road and see Fidaa Ataya, a young Palestinian woman, marching abreast with the few remaining from our contingent. She is the coordinator of the Freedom Theater from the Jenin Refugee Camp and one of our partners in creating the residency.

On the final approach, soldiers emerge on foot from the gate. Evenly placed every two meters, they no longer shoot tear gas canisters into the air, instead, they shoot directly at us. As the soldier in front of me levels his rifle, I stumble up a hill blinded by flash grenades and teargas, barely step over smoking canisters and lines of concertina wire laid on the ground to trip up people exactly in my predicament.

I reach the top and after a while I am able to stop crying, gagging and coughing. The wind is to my advantage so I take a breath and make my way down again. Fidaa has been shot. She is in a stretcher and I grab her hand as she is carried back to an ambulance that slowly makes it way towards us. A canister has grazed her leg. The bleeding has stopped.

That evening I show slides of past work to members of our contingent and my younger Palestinian collaborators. They see photos of me when I was their age, as member of a muralist brigade in Nicaragua during the 1979 Sandinista Literacy campaign. I show them images of murals painted in other locations where violence, poverty and struggles for cultural survival also coincide.

‘Akkub is the witness: our murals are part of ongoing creative efforts to use non-violent direct action in Bil’in. Cultural activism helps us have the conversations that must occur, helps us create common goals while we strive to co-exist with the painful memories and powerful cultures that exist on both sides.

As we approach our day of departure, my Palestinian collaborators tell me they want to form a muralist brigade and continue the kind of work we have carried out in Bil’in. They decide the name should be Warda or Flower Brigade. Warda is also a woman’s name meaning guardian or protector.

Our murals may remain or disappear, the words painted on the walls, CLIMB, RETURN and SUMUD صمود (persist) will certainly fade, but our actions will catalyze the future actions of others as they build on the possibilities we have planted. Sumud.

Everything happens for a reason. After two weeks of a creative artistic workshop in the streets of Bil’in, we discovered that the reason of our meeting was to share knowledge and passion and explode our energy in arts as Palestinian artistic youth. We learned the spirit of teamwork, helping and sharing our thoughts, dreams and personalities. To be honest, it was hard to see you leaving and packing your stuff heading home. You gave us the best you have and we too gave the best we have. We wish to see you again and share new things with you and to see more smiling faces, the same as those we left in Bil’in. Welcome to Palestine, with all LOVE. Warda Brigade.

—Aram Shbib, Ramallah

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)