The maelstrom created after the screening of the Palestinian-Israeli "solidarity film" No Other Land, at the 2024 Berlinale, further consolidates the accusations of anti-semitism long been used in Germany to silence criticism of the state of Israel. After October 7, they have become an all too handy excuse to cancel demonstrations, criminalize protesters, shut down cultural institutions and award ceremonies, to defame artists and academics and prevent them from expressing their opinions freely.

This year, during the 74th edition of the Berlinale, considered one of the five most important film festivals in the world, the selection committee dared screen No Other Land, an Israeli-Palestinian documentary film about the situation in the West Bank. Unsurprisingly, given the current climate in Germany, the film and its team created waves: Waves of empathy, waves of dismay, anger and ultimately political opportunism — all produced primarily by politicians and the media. Depending on the tides, waves can either gather destructive momentum or dissolve into foam. This one became a storm in three parts.

Part One. During the opening ceremony, the director of the Berlinale, Mariette Rissenbeek, took to the stage and gave an unexpectedly moving and politically balanced speech. She began by remembering Hanau, where several people were killed for racist motives five years ago. She went on to talk about the heavy baggage that would be carried into the festival:

“The war in the Middle East: it continues. We see the immeasurable suffering of the people in Israel and Gaza. The war is a humanitarian catastrophe and we call for everything possible to be done to protect the lives of civilians. We extend our deepest sympathy to all victims of the humanitarian crises in the Middle East and elsewhere. (…) The Berlinale has a lot of room for dialog between people and art… explicitly opposed discrimination and any kind of hatred — whether anti-semitism or anti-Muslim hatred.”

Minister of Culture Claudia Roth, on the other hand, appeared on stage to reaffirm the current German “reason of state” with the usual wording. She spoke of “the barbaric attack by Hamas terrorists on people living peacefully” and repeated the call to “bring them home!,” i.e. the abducted Israeli hostages. Eventually she also expressed some concern for the civilian population in Gaza, combined with the suggestion to do more to ensure their safety (a contradictory call, given that the German government had just stopped supporting the aid organization UNRWA).

Part Two: Despite calls for a boycott of Germany due to its unreserved support of Israel in the recent Gaza war and the sanctioning of voices critical of Israel, the Palestinian-Israeli film in question was screened as part of Panorama. No Other Land was directed by a Palestinian-Israeli collective of four activists: journalists and filmmakers Basel Adra, Yuval Abraham, Hamdan Ballal and Rachel Szor, who acted as the film’s cinematographers and editors as well. The premiere took place at Kino International with a visible police presence outside and a huge press cohort inside. At the end of the screening — received with standing ovations — all eyes and cameras turned from the screen to the audience.

Most of the comments from the audience were heartfelt and moved by the overwhelming evidence of the inhumanity of everyday life under occupation in the West Bank. When a German man attempted to push back and defend Israel, he was drowned out by shouts of “Free Palestine.” (I admit I was curious to hear what he might possibly say in defense given the film we had all watched). In the days that followed, the headlines naturally focused mainly on this incident.

Part Three: During the closing ceremony of the Berlinale, No Other Land received two prizes, the jury award and, more importantly, the audience award. Two members of the collective, Basel Adra and Yuval Abraham, appeared on stage to receive them, each giving a brief acceptance speech. First, Adra:

“I’m here celebrating the award, but it’s also very hard for me to celebrate when there are tens of thousands of my people being slaughtered by Israel in Gaza. Masafer Yatta, my community, is being also razed by Israeli bulldozers. I ask one thing from Germany, as I am in Berlin here, to respect the UN calls and stop sending weapons to Israel.”

Then, Abraham:

“In two days, we will go back to a land where we are not equal. I am living under civilian law, and Basel is under military law. We live 30 minutes from one another, but I have voting rights, and Basel has no voting rights. I am free to move where I want in this land. Basel is, like millions of Palestinians, locked in the occupied West Bank. This situation of apartheid between us, this inequality, it has to end.”

Both directors received strong applause, though a few guests at the awards ceremony stood up and left the hall in protest. As expected, the reactions of German politicians and the press were dominated by accusations of anti-semitism. The Berlinale was reprimanded for its supposedly one-sided support of the Palestinian cause, because the Israeli victims of Hamas on October 7 were not mentioned during the award ceremony. The Green politician and Minister of Culture Claudia Roth, mentioned above, who was caught on camera applauding as well, made the astounding statement that her applause had only been meant for the Israeli filmmaker, not the Palestinian.

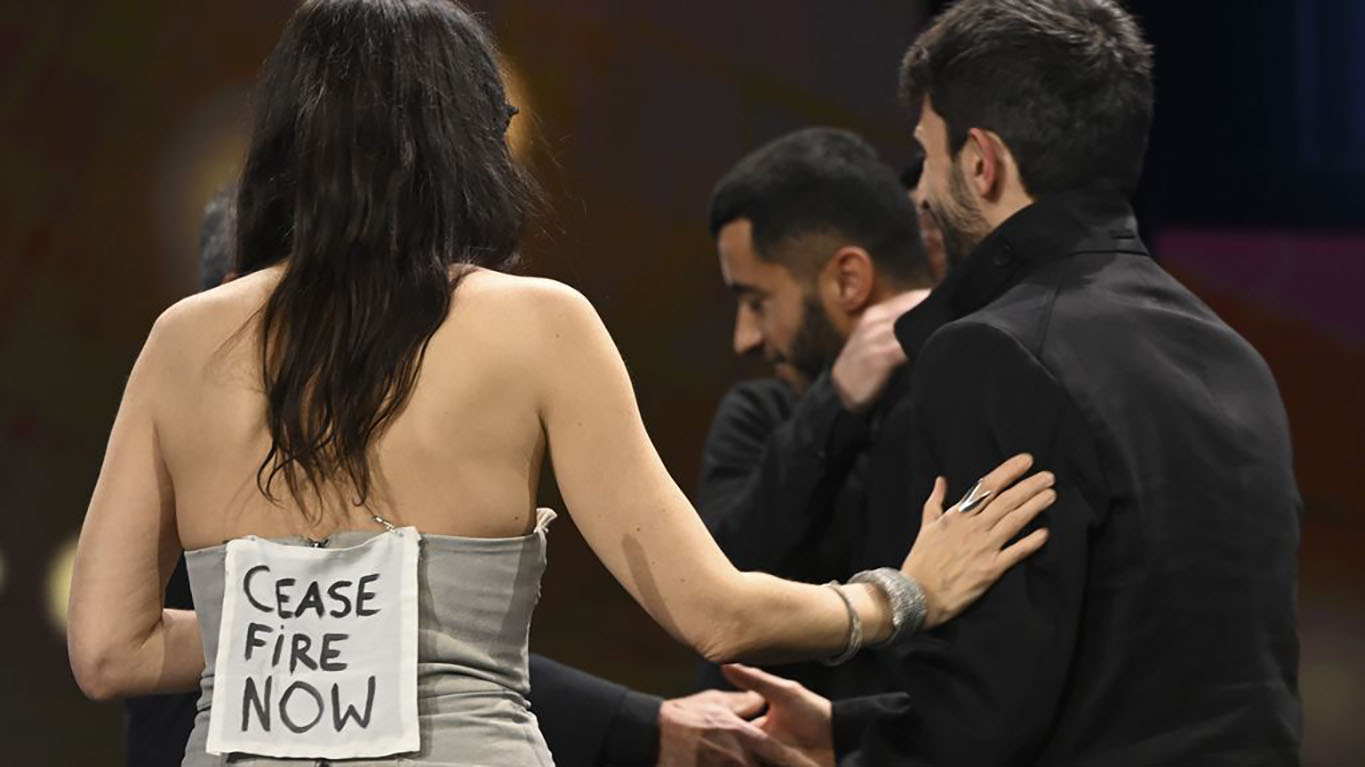

The cultural magazine Die Zeit reported other reactions, such as that of Berlin’s Governing Mayor Kai Wegner (CDU) comments on X: “What happened yesterday at the Berlinale was an unacceptable relativization. There is no place for anti-semitism in Berlin,” he went on, “and that also applies to the art scene.” He expected, he said, that “the new management of the Berlinale [would] ensure that such incidents are not repeated.” Even the taz (the German daily paper Die Tageszeitung), which used to be known for its left-wing orientation, ran with the sensationalist headline: “Anti-semitism at the Berlinale.” The accompanying photo implied that the demand for Ceasefire Now, which jury member Verena Paravel had pinned to her back, constituted a display of anti-semitism.

Given these reactions, it was little wonder that the following day, filmmaker Yuval Abraham reported that he had received death threats and that his family in Israel had been threatened by a mob. He was forced to postpone his journey home for security reasons. [While Abraham was attacked in the Israeli press, including in the left-leaning Haaretz, on March 6, a columnist in the same newspaper called Abraham “a true hero” for his work on the film. ED]

Accusations of anti-semitism have long been used in Germany to silence criticism of the state of Israel, but after October 7, they became an all too handy excuse to cancel demonstrations, criminalize protesters, shut down cultural institutions and award ceremonies, to defame artists and academics and prevent them from expressing their opinions freely.

Nor have Jewish voices been exempt from these accusations. Just as happened with Yuval Abraham, Jewish artists who criticize failures of Israeli policies find themselves in the crosshairs of German criticism. Members of the Jewish Voice, for example, have been targets for harassment ever since their organization was nominated for the 2019 Göttingen Peace Prize. One of its representatives, trained psychologist Iris Hefets, has on several occasions analyzed the obsessive German alignment with Israeli policies as an attempt to identify themselves with the (Jewish) victim, seeking redemption from the guilt of being responsible for the Holocaust. This redemption, unfortunately, is only had at the expense of Palestinians and Arabs in Germany who express their solidarity with their kin, as well as other voices critical of Zionism, racism or the neo-liberal world order in general.

It is in this climate that No Other Land generated the storm that it did. And yet, despite all the controversy surrounding the screening, the film’s actual content was almost totally ignored by the press in Germany, and the harsh reality it documents provoked no outrage from either German media or politicians. The subjectively narrated documentary, whose two most important protagonists, Basil Adra and Yuval Abraham, can be seen almost continuously onscreen, invites us to follow the struggle of the people of Masafer Yatta against the eviction and demolition of their houses: a close-up view of the intricate cruelties and bureaucracies of the occupation.

Since its inception, Palestinian filmmaking has faced the daunting question of how to portray the struggle for liberation, and how to make itself heard when the powerful occupy not only the country but also international media channels. This was a particularly vital issue at a time when film was still produced in analog form and had to be developed in laboratories at great expense and effort. In 1967, after the rest of Palestine was occupied by Israel, the first Palestinian film unit was established in Amman, Jordan, coinciding with a new era of militant resistance against the occupation. Founded by cinematographer Sulafa Jadallah and directors Mustafa Abu Ali and Hany Jawhariyyeh, they saw the film unit as part of the Palestinian liberation movement. Given that reporting on Palestine in the West was up to that point completely dominated by Israel and its allies, the film unit felt obliged to provide a counter-narrative with their short films. In March 1968, they documented the Battle of Karameh and thus were able to provide a counter-statement to Israeli accounts of what happened.

This is not the place to expand on the important position that Palestinian filmmaking has since acquired in international film history, but it must be said that while education and counter-propaganda were important goals, those first filmmakers had much wider visions. They also endeavored to portray their own culture and develop their own film language with which they could reach and encourage the people in the refugee camps. in the fictional, experimental and documentary fields.

While it also provides a counter-narrative, No Other Land in fact belongs to a different filmmaking tradition: because it was made in collaboration with Israelis, it may be considered a solidarity film. According to its makers, its role models are in fact fly-on-the-wall films in the style of Arna’s Children (2004) by Juliano Mer-Khamis and Danniel Danniel, as well as 5 Broken Cameras (2012) by Emad Burnat and Guy Davidi, rather than films by Palestinian filmmakers such as Michel Khleifi, Rashid Masharawi, Raed Andoni, Azza El-Hassan or Jumana Manna among others who excelled in observative, creative and subjective documentaries alike.

No Other Land makes the stakes clear from the outset. The opening scene sees Adra fleeing from the approaching Israeli military jeeps that are once again invading the area around his home village of Masafer Yatta, near Hebron, West Bank, at night. The film shows us that Adra has in fact been in front of the camera since childhood; for more than a generation, his family and the villagers have been fighting against the expropriation of their land. Though his father was persecuted by the military and imprisoned several times, Adra manages to get away every time because he is such a fast runner.

Very soon it becomes clear that despite the Oslo Accords of 1990, which supposedly granted Palestinians the right to self-governance in the West Bank, Israel’s policy of expulsion and settlement continues unabated in the de facto occupied territories. More and more land is emptied of its original inhabitants through a series of bureaucratic steps: first it is declared a restricted military area, then the army follows to enforce this ruling, and finally the militant settlers arrive. Abraham and Adra document each step of this, filming day in, day out, nearly house by house, family by family, over the course of around five years until shortly before October 2023. This is a decades-long tactic, for the more protracted it is, the less the world pays attention. It is characterized by the surprise deployment of ground troops, house searches, confiscations, arrests, destruction of water wells and power lines, short-term demolition orders whereby houses and stables are mercilessly razed to the ground within the course of a few hours and unarmed Palestinian civilians are occasionally shot.

The film also documents the influx of non-Palestinian activists who oppose the unlawful appropriation of land. One of them is Yuval Abraham, about the same age as Adra. From early on, their exchanges, their budding friendship and growing bond in the wake of the military actions determine the rhythm of the movie.

While they remain the backbone of the film, there are also several other narrative threads, including the story of Harun. During one of the demolitions, Harun, unarmed, holds on to the small power generator that the military is trying to snatch from him. A soldier shoots him in the chest at close range, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. For two years, Harun’s mother, whose home has also been demolished, nurses her son inside the cave where they sought shelter. A stream of journalists passes through the place to document the story, but no help actually comes. Harun and his family must either remain in the cave and guard their land or give it up and move to the city. The only end is the tragedy of Harun’s untimely death.

The village school forms another important narrative thread: as the Israeli occupation refused to grant a permit for the construction of a school, it was built secretly in day and night shifts. The women worked during the day as they had no fear of arrest at the time, and the men at night. During Adra’s childhood, Tony Blair, the British Prime Minister, visited the school and helped prevent its planned demolition. But the film documents this untimely end as well: the bulldozers arrive unexpectedly and the schoolchildren are hastily evacuated through the windows. An unarmed cousin of Adra’s is then shot dead by a settler on the street at point-blank range.

At this point, several families decide to give up. Their departure precludes any return, because once Palestinians vacate their properties, even if they hold all the deeds, they still lose any claim to it according to military law. It is precisely this legislation and the unequal treatment of Israelis and Palestinians that incited Yuval Abraham to use the word “apartheid” during his speech in Berlin, a word which, like “genocide,” has been put on the official list of taboo terms in Germany. Thus, we have the absurdity of the Israeli Abraham unable, on a German stage, to deem his own experience of his own country as a form of racial segregation without being accused of anti-semitism.

Apart from depicting the discriminatory practices of the occupation, No Other Land also destabilizes our system of audiovisual representation permeated by power structures. As early as the 1970s, when the Jordanians cracked down on the armed Palestinian resistance movement during a period now known as Black September, French filmmaker Jean Luc Godard was arguing a point still relevant to this day. His film essay Ici et Ailleurs (1976), in reflecting on the reception of the Palestinian cause in France as well as on the documentary material he himself gathered among the resistance fighters before the events in Jordan, argues that the media representation of the Palestinian conflict was based on a polarization between fiction and documentary. Fiction, i.e. narration, he claimed, belongs to the Israeli side, documentary to the Palestinian. What does this mean in concrete terms? Narration grounds us in a realm of characters and emotions, visceral and sympathetic, while documentary relies on facts and figures. It is based on abstraction and thus harder to empathize with. This rift remains to the present day, and is particularly glaring in the German media coverage of the issue.

Ever since I can remember, reporting in Germany has followed exactly this pattern. In the news, we learned the names and individual fates of Israelis, but not of Palestinians. Victimhood with its invitation to empathy seemed to exist on one side only (not to deny of course that it was often the other way around in Arab reporting). Palestinians, on the other hand, are portrayed either as a mass of aggressively screaming people, or as anonymous numbers of dead and displaced. Muhammad al-Durrah, the Palestinian boy who was shot dead in his father’s arms on camera in 2000, was one of the first cases in the news in which a name and a story was provided along with the report of an anonymous Palestinian tragedy.

What No Other Land achieves is a blurring of the boundary between documentary and narrative; finding a balance between material traces and unspeakable suffering, the documented events get enriched with subjectivity and individual human destinies — something that Palestinian filmmaking in general be it documentary form or fiction has achieved during the past five decades. With No Other Land it has again allowed Palestinians to step out of namelessness. We see them socializing, laughing, crying, eating. Children are caressed to sleep by loving parents. Evening conversations between Adra and Abraham show us the development of their friendship up close. While Adra smokes his water pipe, Abraham complains that his articles are not making much of a difference. The young Palestinian urges him to be patient. It will take many more years to effect change. But then Adra wonders when they might have time to start families themselves. At several points, Abraham is questioned by other men about his origins; when he comes out as an Israeli, he is briefly teased, then accepted into their midst with humor. Alongside the apparent hostilities in the film, the aggression on the part of the military and the settlers, this unquestionable space for cooperation and human solidarity is for me the quintessence of the film. The only troubling question that lingers is when and how such cooperation and solidarity will be admitted into the mainstream German narrative, following the example of the Berlinale.