The appetites of museumgoers in Los Angeles are enlivened by the exhibition Dining with the Sultan: the Fine Art of Feasting, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until August 4th, 2024.

Philip Grant

The 10th-century historian al-Mas‘ūdī reported, toward the end of his monumental Meadows of Gold, that one day his contemporary in Baghdad, the Abbasid caliph al-Mustakfī (r.944-46), ordered his guests to recite poetry about food. In the Iraqi historian’s narrative, there follows a succession of poems which so delight the caliph that after each recitation he commands that the dish so lovingly described be straightaway prepared and brought. When one guest recites Kushājim’s poem about asparagus, the caliph responds that something of that description is not to be found in Iraq in this season, and they should write to his governor in Damascus to have some sent. The poem ends:

fa-law raʾāhā ʿābidun aw mujtahid

afṭara mimmā yashtahīhā wa-sajad

And were an ascetic to see it, or a mujtahid

So much would he desire it, he would break his fast and prostrate himself

Another poem, attributed simply to “a recent writer” praises harīsah — the ancestor of the porridge known by that name in the contemporary eastern Arab-majority countries and Armenia, rather than the spicy Tunisian condiment — although this is a rather grand version, including a plump goose, almonds, chickpeas, butter, tail fat, kidneys, and galangal.

wa-yashtahīhā l-ahlu wa-ḍ-ḍīyfān

lahā ʿalā aḍrābi-hā s-sulṭān

Familiars and guests alike desire it,

While the sultan delights in all the forms it comes in.

Once again, we hear that someone fasting will scarcely be able to contain themselves when confronted by the sight of this dish. The poet also declares that it was invented by none other than Sasan, eponym of the by then long defunct Sasanid dynasty of the Late Antique Iranian Empire, as well as enjoyed by the king who epitomized just rule in medieval Arabic and Persian literature, Khosrow Anushirvān. And in a rare reference to the actual labor that made these splendid dishes, we are told it is best if it is:

…harīsatun yaṣnaʿuhā n-niswān

la-hunna ṭību-l-kaffi wa-l-īqān yujmaʿu fī-hā aṭ-ṭayru wa-l-ḥumlān

… a harisa women make

With goodly, skilful hands; in it are gathered birds and lambs

We are made hungry by the exhibition Dining with the Sultan: the Fine Art of Feasting, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until August 4th, 2024, just as al-Musktafī was by his courtiers’ recitations. In our case, a rumbling stomach is provoked by objects in glass cases, not by poems. Around some of these dances an aura, stemming less from their unreproducible character as from the combination of their sheer antiquity and their eminent breakability. I have been researching the Zanj Rebellion (869-83CE) in Iraq and Iran for a little while now, meaning that those objects that join me to the world that ends with the unfortunate gourmand al-Musktafī are those that have the most urgent pull on me. Tripod dishes from 9th-century Iraq and Iran (cats. 64b, 67a, 67b); a multiple compartment dish from 8th-century Iraq (64a); lusterware bowls from 9th and 10th-century Iraq (68a, 68d), specifically one from Basra (68c), which I imagine occupying its rightful place on the sufrah of some notable of that great city, sitting with his guests, picking over the bones of one of their failed sorties against the nascent Zanj uprising as it took shape along the many canals on the outskirts of the town. Or, if we are already astonished at how something as fragile as a handblown glass bottle has survived since it was first manufactured in 12th or 13th-century Iran, we are all the more amazed to see two of them (cat. 13b, c), and stupefaction sets in when confronted with an Egyptian or Syrian glass bottle (13a) that is contemporary with the Umayyad caliphs, five or six centuries before.

If aura is the product of age and fragility, it seems here to attain its maximum, yet this is by no means the oldest object in the exhibition. Objects from the first Islamic centuries rub shoulders with their Sasanian predecessors, reminding us of the many continuities between Late Antique Iranian courtly culture and the Abbasid courts of Baghdad and Samarra, where the ghosts of exemplary Sasanian monarchs were never far from the scene, including in matters culinary: Ibn al-Sayyār al-Warrāq’s 10th-century compendium of recipes has a number of dishes whose genesis was attributed to Sasanian imperial command. Silver gilt bowls (cat. 60b, c) and a flask (60a) with dancing female figures from the Sasanian period stand next to two, large silver gilt forks (63a, b) attributed to some time between the 8th and 11th centuries. And yet… scarcely recovered from my encounter with the 8th-century glass bottle, I happen upon a cabinet with two pieces of Sasanian glassware, a transparent blown and facet-cut cup with geometrical and arch patterns, used for wine drinking (61b, 4th to 7th centuries), and an opaque green bottle with polished hexagonal facets (61a, 4th to 6th). I want to remonstrate with my fellow visitors. “But how is it possible… you see…”

There is no uninfluenced culture. The catalogue notes that the difficult facet-cutting technique (cutting designs onto the surface of the cold glass vessel) was earlier practiced by the Romans, while Sasanian ceremonial and techniques would shape Abbasid court culture as well as material production. Abbasid ceremonial, including feasting practices, would in turn have a profound influence on sultans and other rulers and notables across the Islamic world and beyond for centuries to come. If the narrator of our banquet reports, rather sadly, that al-Mustakfī, delighted with how it went, rewarded all his guests, singers, and musicians handsomely, despite the depleted state of his treasury, yet that there would be no such gathering at his court again (deposed, replaced by a cousin, and then blinded, he died in imprisonment in 949), plenty of other powerful patrons would take up the reins of hospitality in the future.

Much of the material on display was designed to invoke a sense of wonder through its patterning, its colors and their luster, through its simultaneous presentation and effacement of the technical mastery this required. Artisans were anything but members of the elite, and it is not hard to imagine the amazement of the guests in western Iran or Iraq who, sometime around 1220CE, washed their hands using an exquisite brass ewer, inlaid with silver, gold, and copper (cat. 34a), even as they likely had no more idea how to manufacture one than most of us could assemble the computer I am currently writing on. And if the guests were impressed, and perhaps determined to emulate or surpass their host with a commission of their own, how should we imagine others’ responses to it? Might the servants who cleaned and polished and filled it have been astonished and fascinated? Proud of their attachment to so glorious a house? Sometimes envious, or rather contemptuous? Sick of the sight of it?

Damascus Room (detail), 1766–67 CE/AH 1180, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Conservation of the room was organized in partnership with the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture; additional conservation support was provided by the Friends of Heritage Preservation, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

There are, however, at least two pieces from what might be broadly termed the medieval world where the artisan has not gone entirely anonymous: one is the brass jug inlaid with silver and gold from late 15th-century Herat (cat. 117a), autographed by one Ḥusayn ibn Mubārakshāh; another, a much simpler unglazed fritware canteen inscribed “made by al-Mufīd” from 15th-century Syria or Egypt (53a); the catalogue notes do not tell us anything about either individual; perhaps nothing is known. The assemblage of fritware statuettes of a Turkman milking a water buffalo while her calf stands by (82b), from Raqqa, Syria, around 1200, is striking at once for its presumably unusual subject, its lack of practical use, and the fact that it does not obviously appear to be a virtuoso statement of artistry or display of wealth, although alongside it a fritware, overglaze luster-painted jar also from early thirteenth-century Raqqa (82a) was apparently an expensive container for buffalo milk.

It is easy to forget that deeply unequal relations of production made these objects possible. If we have any function as historians, it is to restore this context, including the labors of all the people who made these things possible, and not just those who gloried in their possession.

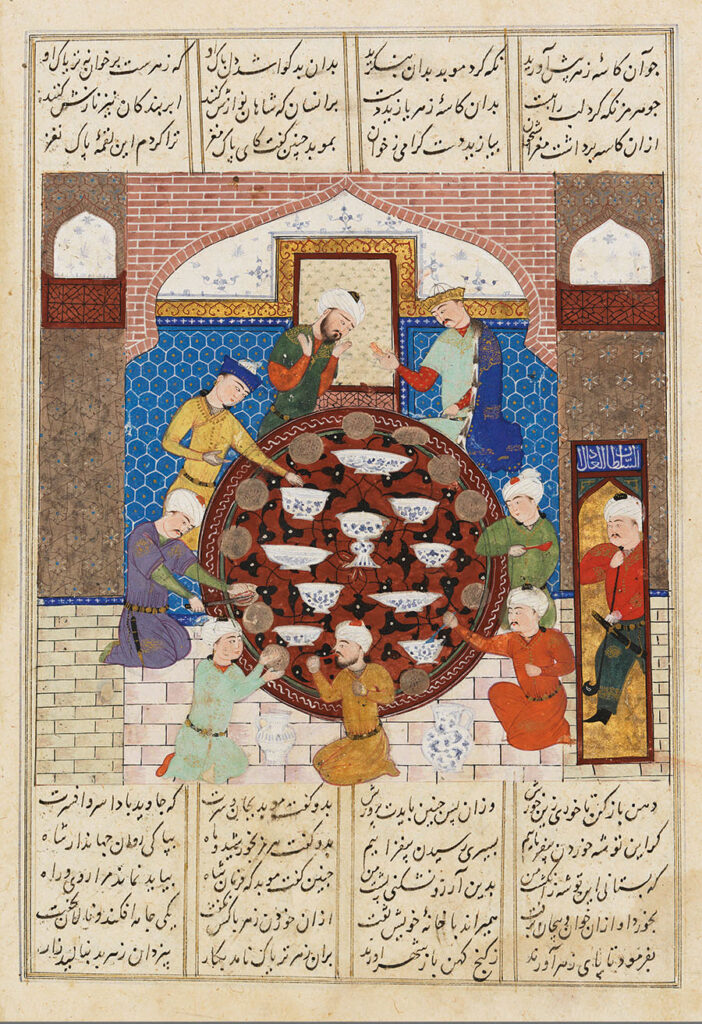

While jars and dishes are the most represented objects in the exhibition, there are a number of manuscript pages too. A folio shows us a man seated under trees preparing medicine from honey, from a 13th-century Baghdadi manuscript of Dioscorides’ De materia medica (cat. 97). The caption tells us nothing more about this text, but Dioscorides’s first century CE Greek text On Medical Materials was first translated into Syriac and Arabic in 9th-century Baghdad and improved by Al-Ḥusayn ibn Ibrāhīm al-Nātili in Samarqand toward the end of the 10th; it remained influential in the Islamic lands and in Christian Europe until the early modern period. The 15th-century illustrated Tacuinum Sanitatis manuscript from Italy (96), placed next to a 13th-century Syrian manuscript of the Taqwīn as-Ṣiḥḥah (“the Almanac of Health,” the Italian title Latinizing the Arabic taqwīn, cat. 95) by widely-traveled 11th-century Christian Baghdadi doctor Ibn Buṭlān (also author of a widely-circulated guide to purchasing slaves), reminds us that the influence of medieval Islamdom’s culinary-sanitary regimes extended well into Latin Christendom. Their material culture too: two 14th-century Syrian albarelli are flanked by two near-contemporary Valencian examples. The word albarello comes from the Italian, as 15th-16th-century Italy was a major production center for a version of these tall, narrow storage jars, earlier manufactured in Egypt, Syria, and Iran. Meanwhile, many objects on display have an obvious Chinese influence. There are a number of Chinese items on show, like the cups, stands, and bottles from the Song and Yuan dynasties (12th to 14th centuries, cat. 121a-d); while the juxtaposition of the Tang dynasty (8th century) bird-headed ewer from Shanxi, China, and a rooster-headed ewer from Iran, four centuries or so later (71b, 71a), makes the point clearer. Tang dynasty pottery had already profoundly influenced production in Iraq and Iran in the ninth century, however, and just as Renaissance Italian maiolica (e.g. 126c) owes much to Andalusian lusterware without being merely derivative, so too the white-glazed, earthenware bowls of Basra and Susa, with their cobalt-blue designs, were creative responses to the Chinese pottery so admired by 9th-century Abbasid elites, rather than simple imitations.

The temporal scope of the exhibition is vast, since it takes in Ottoman sultan Abdulhamid II (r.1876-1909)’s silver coffee and tea set (ex-cat.), and Qajar oil paintings like Ismail Jalayir’s magnificent ‘Women around a Samovar’ (c. 1870, cat. 93), where the (originally Russian) samovar is almost lost in a composition where eleven women of Naser al-Din Shāh’s harem, seated and standing, looking in various directions, take up center, left and right stage, and the young woman seated to the left of the tea-making equipment, smoking a pipe and gazing directly at us, eyebrows slightly raised, seems to be saying, “though we are displayed here for you to see, you can never know us.” It also includes a cookery book from the court of the same monarch (r.1848-96). Here there is a sense we have definitively entered a different world, as the book was commissioned by the Iranian king’s French physician so that, furnished with a precise sense of knowledge of the royal diet, he could better treat his patient.

There is too much in this exhibition to do justice to, even in a review of this length, but mention must be made of the beautiful collection of 19th and early 20th century musical instruments, the most spectacular of which is surely the Indian taus (“peacock”), a four-stringed bowed instrument with a body carved in the shape of that bird, and actual peacock feathers attached to it (cat. 105a); recordings of this and other instruments are available.

We can revel in the beauty of these objects, despite being aware of the differentials of power embedded in them, that made them possible. Witness the colorless glass dish from Mughal India, c.1700, whose enamel and gilt decoration sparkles as if it were gold (cat. 24a); or the engraved bronze pestle and mortar from early thirteenth century Khurasan, magnificent and massive (98). We can also delight in their inventiveness and charm, as with the “sphero-conical vessels” for beer, from Syria or Egypt (44a) and Kashan, Iran (44b). Yet if I keep returning to the theme of power, it is because the title of the exhibition and the sumptuousness of many of the objects invite it. Presented like this, abstracted from context, it is easy to forget that deeply unequal relations of production made these objects possible. If we have any function as historians, it is to restore this context, including the labors of all the people who made these things possible, and not just those who gloried in their possession.

The depiction of an “automaton of a girl offering wine to the king,” from an early 13th-century manuscript of al-Jazarī’s early 12th-century Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices (35) is a case in point, crying out for contextualization. Lamia Balafrej, who has written about al-Jazarī’s work, has argued that the reason that automata are often depicted as jawārī, enslaved women who performed domestic labor (by no means necessarily “girls,” a possibly demeaning term here), was that jawārī symbolized mobility, visibility, and serviceability. They were also understood as “instruments” (ālāt), simultaneously objects that enabled a usually male elite owner or patron to accomplish a task, and subjects capable of dynamic performance of their labor. Nowhere, either in the exhibition label or in the catalogue entry, do we learn of the automaton’s status as a jāriyyah, only that “the design reflects the ingenuity of al-Jazari and the centrality of wine drinking and novel entertainments at the royal court”— a replication of an elite male perspective of eight centuries ago if ever there was one.

There is very little in the way of explanation in the exhibition other than a handful of computer screens by the entrance providing us with maps and some general comments on the “agricultural revolution” brought about in the wake of the early Islamic expansion, with a variety of crops (e.g. citrus fruits, aubergine) moving from east (often from India) to west, as far as al-Andalus and then beyond to Christian Europe. No doubt a profusion of explanatory signs would have given the whole a cluttered feel, and perhaps many people do not care for reading so much text anyway; yet regardless of one’s origins, most of the objects in this exhibition will be deeply unfamiliar to the public.

As a published scholar of early Islamic history, I have a context for many of these items it would be unfair to expect most members of the public to possess, but even so writing this review required further research, including reading the exhibition catalogue with its helpful descriptions and insightful essays. Nonetheless, I would not venture to offer a comment on much of the material on display here. There is plenty of explanation on offer in the neighboring exhibition on the propaganda arts of the First World War, at least some of which must be much more familiar to most visitors, without it ever feeling overwhelming. Why not something similar for these objects that reach us from worlds far more distant?

A final gripe, even as I must acknowledge the impressive selection of objects presented to us and the great care and thought that has gone into their arrangement: this is still too much of an old-fashioned, things-in-glass-cases exhibition. It is true that there are three exhibits described as “immersive installations”: a large video projection by Iraqi artist Sadik KwaishAlfraji that alludes to his late mother’s bread-making; a “virtual meal experience” where we sit on cushions at a low table representing a sufrah on which rotate video projections of six dishes based on historical recipes; and the gorgeous interior of a reception room (qāʿah) from 18th-century Damascus (cat. 28), a beautifully ordered composition of poplar wood and gesso relief, tin and brass leaf, glazes and paint, plaster with stone paste inlays, and multicolored stones, Arabic inscriptions on the upper parts of the walls for guests to contemplate as they ate.

The first reminds us that most foodways have little or nothing to do with dining with sultans or equivalents; the second feels like a gimmick; and the third has been lovingly restored and is clearly well cared for (only four people are allowed inside at once), although rather than imagining a busy reception, my thoughts strayed to envisaging a future when this room could be returned to Syria and displayed there (with a 3-D printed copy staying in Los Angeles); the catalogue simply informs us it was dismantled in Damascus in 1978 when the quarter it was situated in was to be demolished to make way for a road, and that LACMA acquired it in 2014. Whether any of these are “immersive,” or if immersive is anything other than the latest empty buzzword, I will leave readers to determine, but the reception room does at least successfully bridge the divide between the traditional static display-function of the exhibition and the contemporary desire for more dynamic and interactive museum galleries. Presenting often fragile objects of considerable antiquity to a numerous viewing public of course imposes considerable constraints, but it would be welcome to see future curatorial imaginings applied further in this direction, instead of near-contextless glass cases.

My thanks to Nathaniel Miller for correcting my readings and translations.