The graphic novels or bandes dessinées out of Africa are a line in the sand of protest and rebellion against European colonialism.

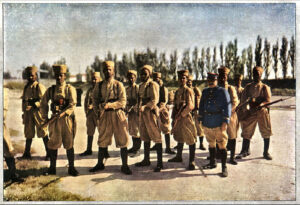

In 2021, Michelle Bumatay, a scholar of Black bandes dessinées, published an article about the rise of Senegalese and French bandes dessinées focused on the tirailleurs (soldiers assigned to fire at will and harass the enemy) during World War I. Bumatay argued that comics such as La patrouille du corporal Samba: Le naufrage de l’Africa (2004), La patrouille du corporal Samba: le tirailleur des les cigognes, L’Homme de l’année 1917 (2013), Demba Diop: Un tirailleur sénégalais dans la Grande Guerre (2013), Sand noir: Histoire des tirailleurs sénégalais (2013), L’Odyssée de Mongou (2014), and Les Dogues Noirs de l’Empire: La force noire (2019) represent a belated attempt to honor the sacrifices of African soldiers in the French colonial army and elicit empathy from readers, while circumventing direct criticism of colonialism and its societal violence against indigenous populations. Consequently, the figure of the tirailleur is intrinsically integrated into the colonial endeavor, with its involvement depicted as a natural progression of history rather than a disturbance of indigenous customs.

Building on an emerging comic trend about Senegalese tirailleurs during WWII, namely Le Tirailleur, Undesirables: a Holocaust Journey to North Africa, and La patrouille du corporal Samba:Tirailleurs Sénégalais à Lyon, let me introduce the concept I propose to call “Inside the Margins,” which captures and defines a current visual movement that serves as a methodological framework within the comics industry. Inside the Margins focuses on works that prioritize the narratives of ordinary individuals, such as Demba Dior, Mongou, Abdeslam, and Youssou through archival and photographic methodologies. The visual texts that fit this conceptual framework do not simply incorporate marginalized voices into established and mainstream European narratives of bandes dessinées. Rather, they completely alter the framework, illuminating the complex violence of forced migration, militarization, and postwar bureaucratic neglect of indigenous colonial soldiers and labor providers. As such, Inside the Margins signifies a historiographical and ethnographic transformation. It presents a writing approach that emphasizes the lived resilience of individuals affected by Europe’s conflicts, rather than the spectacle of war or trauma, which are often neglected in contemporary historical narratives. This artistic and historical approach positions these marginal narratives within the framework of mainstream bande dessinée while simultaneously emphasizing their significance for comprehending world history. Instead of seeking space within the hegemonic narratives, Inside the Margins creates their own space within their own logic and stakes.

The tirailleur regiment was founded in 1857 on the directive of Louis Faidherbe, the French colonial governor of Senegal. It was established as a light infantry unit of sharpshooters, composed of recruits from French colonial territories who were trained to engage in skirmishes in advance of the primary military column. In World War I and II, the tirailleur epitomized the dual themes of victimhood and agency intertwined with France’s colonial dominance and the oppression of its colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Contemporary artists and authors are utilizing the bande dessinée, a visual medium historically linked to colonial artistic production, propaganda, and indoctrination, especially in the metropole, to create a space in which the voices of those forgotten by histories and stories told about the wars in which these tirailleurs participated are recovered, enabled to speak, and given their fair share of the oversaturated terrain of history and memory. They are also contesting the assumed vulnerability and complicity of the tirailleur by showcasing varied personal narratives and historical trajectories of soldiers and workers.

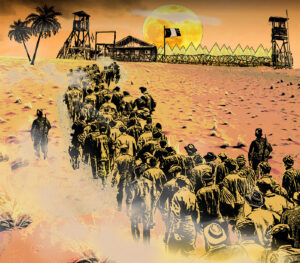

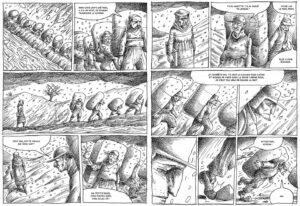

Published by Futuropolis, Le Tirailleur, authored by Alain Bujak and illustrated by Piero Macola, presents a visual narrative about the youth and old age of a certain Abdeslam who was abducted by the French authorities as a teenager in 1939 and forced into service in the French army against the Nazis. Bujak initiated this project in Dreux in 2008, focusing on a photographic series that documented the everyday lives of former North African laborers who contributed to the reconstruction of post-WWII France and the present retirees residing in Adoma (formerly Sonacotra). Bujak first met Abdeslam when the latter was in his early eighties. Following the conclusion of his photography project, Bujak pursued Abdeslam and initiated a series of personal interviews and morning discussions regarding Abdeslam’s participation in WWII, the Italian campaign against Fascism and Nazism, the Indochina War, and Abdeslam’s present life between his village in northern Morocco and the suburbs of Paris. Bujak meticulously documented every conversation from 2008 to 2009, apprehensive that this narrative would be overlooked. After 2010, he visited Abdeslam in his village in Taza, where he captured a series of photographs of his family and documented various aspects of life in Abdeslam’s village in northern Morocco.

Bujak employs a Jamesian stream of consciousness to highlight a continuum of colonial exploitation and abuse, depicting Abdeslam’s experiences as a child soldier and retired pensioner compelled to reside in France, away from his family and village, to continue to receive the pension he earned for his service in the French army. This method of visual historical and anthropological writing takes the reader-viewer constantly between the past and present, history and memory, forcing a constant reflection on colonial and postcolonial injustice. As Abdeslam crosses the Mediterranean by boat and plane, we are reminded about the continuum of laws that separate Indigenous servicemen from their homelands and families, and from the privileged French and European citizens they had served under the same flag. In 2004, Abdeslam was notified that the French government reinstated a pension law for former tirailleurs, contingent upon their residency in France for a minimum of nine months. Abdeslam relocated to France and established residence in Dreux, approximately 92 kilometers west of Paris. Distance and isolation forced Abdeslam to return to the village and forfeit his pension, which he earned from his service to the French Republic.

Abdeslam’s narrative underscores numerous challenges associated with post-colonial French migration policy and its ties to history. Abdeslam, like thousands of other formerly colonized people, sacrificed the most crucial period of his life to compulsory military service, fighting on behalf of the French Republic and contributing to Europe’s liberation, but the outcome for him has been nothing but denial and loss. Like many tirailleurs during World War I, he has been separated from his homeland and parents in World War II. Unlike French colleagues who served probably in the same units and under the same circumstances, Abdeslam received a nominal allowance for his military service. After their countries’ independence in the late 1950s and the early 1960s, the pension designated for Indigenous soldiers in the French colonial army was suspended for several decades until the early 2000s. By this time, thousands had died, and many had felt the ashen taste of colonial ingratitude. Although the reinstatement of the pension was great news for the survivors, it was a little too late, and the requirements to access the benefits were burdensome. The benefits were almost designed to be forfeited by these elderly men who could not live nine months out of twelve away from their beloved ones. Consequently, Abdeslam, like many of his colleagues, returned to his native village to be with his family and have a high-quality time amongst his people.

Bujak’s Le Tirailleur exemplifies a contemporary wave of ethnographic writing that critiques the deleterious impact of imperial mobilities in the Mediterranean. While, as I show in my co-authored graphic novel Undesirables: A Holocaust Journey to North Africa, European refugees, including Jews and Spanish Republicans, sought refuge in colonized North African countries, North and West African conscripts were sent to Europe to fight against the Nazi military campaign against France. Many were either killed or imprisoned along with other African American and African soldiers in temporary German camps reserved for prisoners of color, known as Frontstalags.

In Undesirables, illustrator Nadjib Berber and I highlight the story of Youssou, a Senegalese tirailleur who came from a generation of infantry soldiers. He fought for France during WWI and was later imprisoned in forced Vichy labor camps in North Africa during World War II. Meanwhile, quite like Léopold Sédar Senghor, Abdeslam was an example of sharpshooters captured by the Axis Powers while serving under the French colonial flag. These “black watchdogs of empire,” as Senghor called them, also suffered from Nazi occupation of France, as many were interned in camps in the Occupied Zone of France.

As previously illustrated, “Inside the Margins” is an artistically motivated, ethnohistorically informed methodology within bandes dessinées that integrates marginalized voices within the panels and strips. These voices have historically been omitted from colonial and postcolonial narratives, despite their substantial contributions to the liberation of Europe from fascism and Nazism. In this context, Bujak’s Le Tirailleur and Undesirables offer an example of a new bande dessinée that uses the colonial frame, panels, and strip to historicize and humanize migrants and refugees. It should be noted that this emerging tradition of tirailleurs comics is also linked to a rising cinematic production that includes, among others, actor Omar Sy, Tirailleurs and Indigènes (Days of Glory). By focusing on the wartime struggles and experiences of these silenced tirailleurs and indigenous colonial soldiers, artists and historians can inform and educate modern readers about the trauma and loss of colonized communities, establishing a foundation for authentic advocacy grounded in recognition and justice, followed by empathy, and potentially instructing future K-12 readers on ways to foster relationships of understanding and cooperation across both sides of the Mediterranean.