To commemorate annual recognition of the Armenian Genocide on April 24th, TMR is publishing two columns, Heritage by Aram Saroyan and Armenian Eyes by Mischa Geracoulis, each of which takes the reader back through personal memories of family and belonging, in the Armenian and American diaspora. See also our Resource Guide to Armenian Culture for a recommended list of writers, artists, filmmakers and more. —Editor

Aram Saroyan

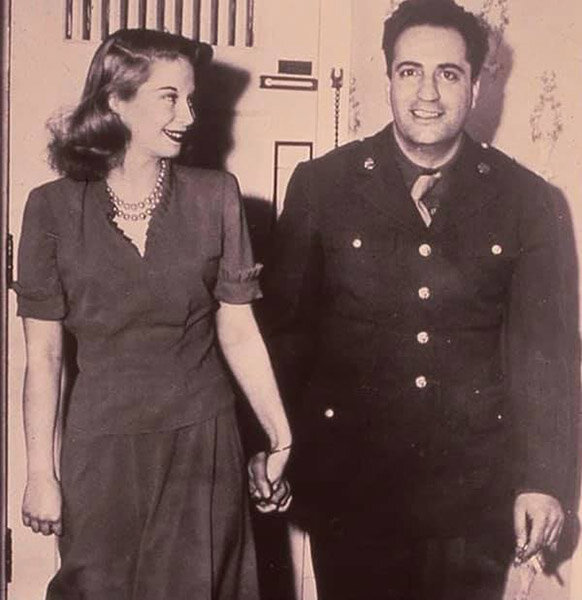

The youngest and only American-born child of an Armenian immigrant family, my father grew up and came of age on the West Coast, a writer out of the loop of the New York literary scene that might have given his career a jump-start. Among his correspondence now at Stanford’s Special Collections Library is a letter from 1928, the year he turned 20, from Clifton Fadiman, then a young editor at Simon & Schuster. Fadiman praises a group of stories he’d received and says he would be very interested in seeing a novel. It would be six more years, however, before William Saroyan would make his national breakthrough with his famous story “The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze.” It was 1934, the depths of the Depression, and the story, with its personal as well as its national resonance, tells of a young writer in San Francisco who over the course of a day succumbs to starvation and dies. At 26, my father had at last hit the note that would bring him not just acceptance, but national and quickly international fame.

By the time the story appeared — the deferred hour of reckoning in a career that in another less determined writer might not have dawned at all —he was already a stylist, master of a prose light years beyond all but one or two of his most accomplished contemporaries. The final two paragraphs of the story, about the last moments of the young writer’s life, read:

He became drowsy and felt a ghastly illness coming over his blood, a feeling of nausea and disintegration. Bewildered, he stood beside his bed, thinking there is nothing to do but sleep. Already he felt himself making great strides through the fluid of the earth, swimming away to the beginning. He fell face down upon the bed, saying, I ought first at least to give the coin to some child. A child could buy any number of things with a penny.

Then swiftly, neatly, with the grace of the young man on the trapeze, he was gone from his body. For an eternal moment he was all things at once: the bird, the fish, the rodent, the reptile, and man. An ocean of print undulated endlessly and darkly before him. The city burned. The herded crowd rioted. The earth circled away, and knowing that he did so, he turned his lost face to the empty sky and became dreamless, unalive, perfect.

_________

Here was an Armenian American writer — and Armenians of his day in Fresno were looked down on — destined to become an international literary sensation, quickly eclipsing the Fresno fame of his uncle, Aram Saroyan, the younger brother of his mother, Takoohi.

Uncle Aram, as he was widely known with a sort of “Godfather” resonance in the Fresno Armenian community, represented the first American success of the Saroyan clan. Assimilation or not, scorned Armenian or not — and houses in Fresno were posted with for sale and rental signs that read “no Armenians” in smaller print — the man commanded respect. A criminal lawyer and the owner of vineyards, he was a powerful physical presence, he had money, he was smart, and he didn’t take no for an answer.

What an urgency to assimilate may not allow for are those issues and particular concerns identified with a culture. When these were taken up in turn by my father, he encountered loud derision from his mother’s brother, the male role-model in his immediate orbit, after his father Armenak Saroyan’s death at 37 when my father was not yet three years old.

“You want to write?” Aram shouted at the adolescent Willie Saroyan after he confided his aspiration. “Learn to write checks!”

That my father eventually succeeded in his literary endeavor to such an unprecedented degree that he became the most famous Armenian of his time, and perhaps in that day the most famous Armenian of all time, had a powerful effect on his extended family at large.

From the beginning, I was identified as the son of a famous American writer, though hardly known that way to myself. I remember one afternoon getting on a school bus in Manhattan, where I was going to kindergarten or the first grade, and having kids point me out to one another. At some point it was suggested that it had something to do with my parents getting divorced. I didn’t know what “divorce” meant, but could see it was news.

Fame in effect reverses the whole assimilation scenario. Celebrity becomes a kind of nation unto itself, one which bestows a special passport on its subject and his family, all of whom know the world a bit differently than it’s known by others. For my father, a flamboyant literary figure of the thirties and forties, fame involved both licenses and personal and professional liabilities. But as he got older, having passed his golden moment and become a parent and then an ex-husband, his persona changed, and some of my fondest memories of him have to do with this change.

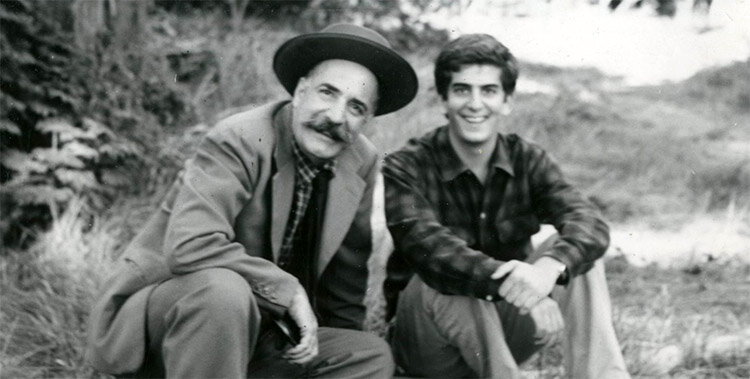

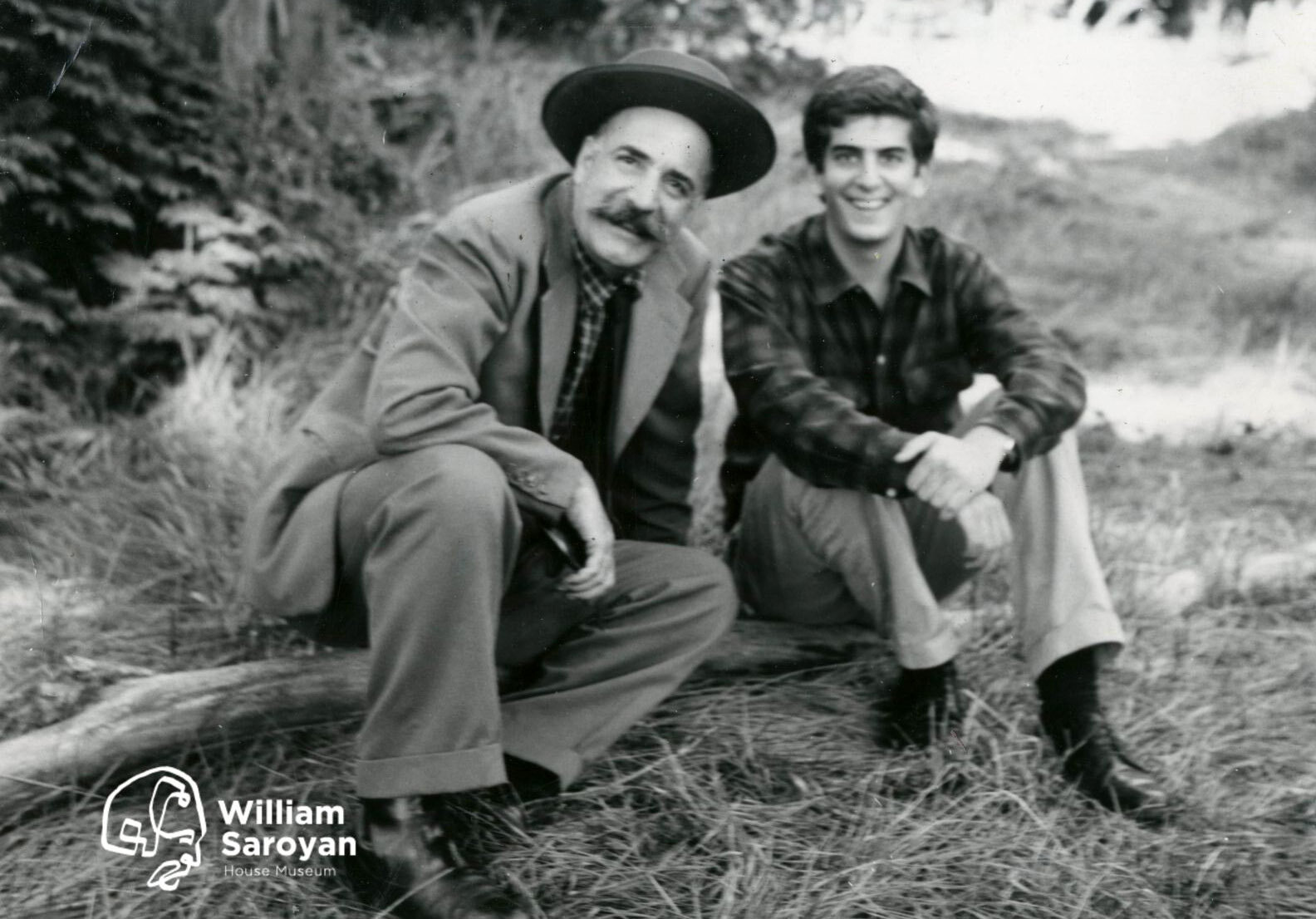

At his height, as the new American wizard of the short story and then quickly the enfant terrible of the American theater, Saroyan became for the 1930s a literary figure comparable to what F. Scott Fitzgerald had been for the 1920s. He was, on the testimony of many, a socially dominant figure, young, handsome, loud, funny and, to use one of his favorite words, swift. Even after his glory days had long passed, he retained that accelerated temper—he was forever moving somewhere, walking, talking, looking, exclaiming at things—and he was the father of a son whose own temper, while similar in certain ways, was generally a study in contrast. I don’t have my father’s speed, and my temper is less exhibitionistic, though not immune to theatrics. What moves me in my memories of him are the times at which, I see now, he recognizably lowered his own natural volume to take in his son’s quieter register. He was interested, in a word, which can’t be said of every father. We spent time together; we discussed many things. The child of a broken marriage that left both parties embittered, I realized rather late in life that, unlike many of my male friends, I actually knew my father; I laughed with him, I saw him in good times and bad. If he could be impossible — and he could be — knowing him was an incomparable gift of my life.

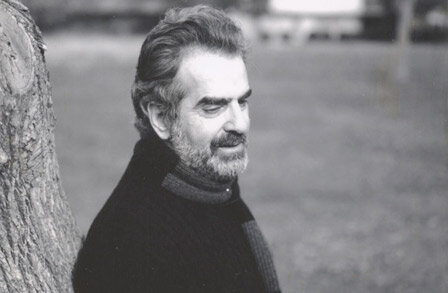

Unlike his immediate predecessor, Fitzgerald, who was gone at forty-four, and his successor, Jack Kerouac, gone at forty-seven — he was a survivor. My father died at 72, and in his later years, while no longer the movie-star figure of his youth, he had recovered his literary balance in a series of memoirs and a late series of stories where he was back at the top of his form.

Having found vocation early on, long before fame found him, he had its support later in his life when much else had been lost, including that fame, his ill-fated marriage, and two children from whom in his last years he was estranged. Nonetheless, he went on writing, went on making his drawings and water colors, and being William Saroyan in the larger literary community that never forgot him. It was an imperishable inheritance he had discovered, and it stood him in good stead in his lean later years. While he’d known a public apotheosis as a writer that only a handful in his century achieved, and the passing of which was fatally punishing for a seeming majority of them, he lived on, perhaps not so unhappily, in the way of an artisan, ever engaged by his art and craft.

In time, too, he came to disdain the particulars of the society that had given him such a wild ride. “We live in a bullshit culture,” he declared in a quiet, bemused tone after he’d done the round of television talk shows upon the publication of one of his later memoirs and seen the sales multiply geometrically. He was a beneficiary of the Oprah Club, as it were, before it existed, but he had known bigger sales before the advent of television and the new wrinkle wasn’t about to rock his world.

By the time I came to know him, then, leaving aside the bitterness he harbored toward my mother, he was a seasoned realist who had toughened and deepened over the years. He imparted to me his love for genuine art in all its forms, and when we were on good terms, it was something we could return to with pleasure.

At the same time, his temper had been damaged by his experience and he turned away from the larger life he might have known in his later years, perhaps knowing that he was constitutionally unequal to it. While a virile, attractive man virtually to the end of his life, he didn’t engage in any serious relationship after his double-marriage to and double-divorce from my mother, and now I think of this as a sad but in certain ways admirable realism. There may even have been in him a concern for the vulnerability of any partner he might have taken on — and there was never a shortage of willing women — perhaps now knowing himself to be more or less inflexibly a loner.

My mother, meanwhile, had found another life, with another man who seven years along in their marriage became a movie star, and yet she remained embittered, and, I believe, was ultimately more engaged by what had happened with my father in her youth than Bill, who had no significant new life afterwards, was himself.

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more