The Iranian regime blamed Nika Shakarami’s mysterious murder on suicide. Her aunt pays homage to her and to the Woman Life Freedom movement.

Once upon a time, not too long ago, Nika Shakarami was a teenager like many others in Iran and around the world. But that changed forever on September 16, 2022.

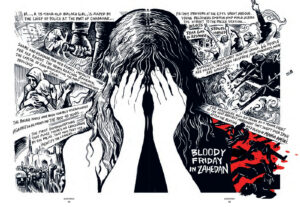

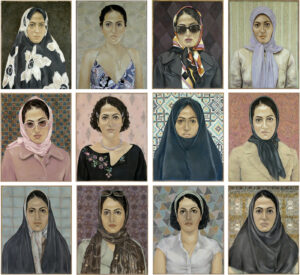

Twenty-two-year-old Mahsa-Jina Amini died as a result of physical violence while she was in custody of Iran’s so-called “morality police.” Her funeral turned into a loud cry against atrocities committed by the regime, especially against women and marginalized communities. Protests erupted across the country, the Woman Life Freedom revolutionary movement was born, and an important page turned in the history of Iran.

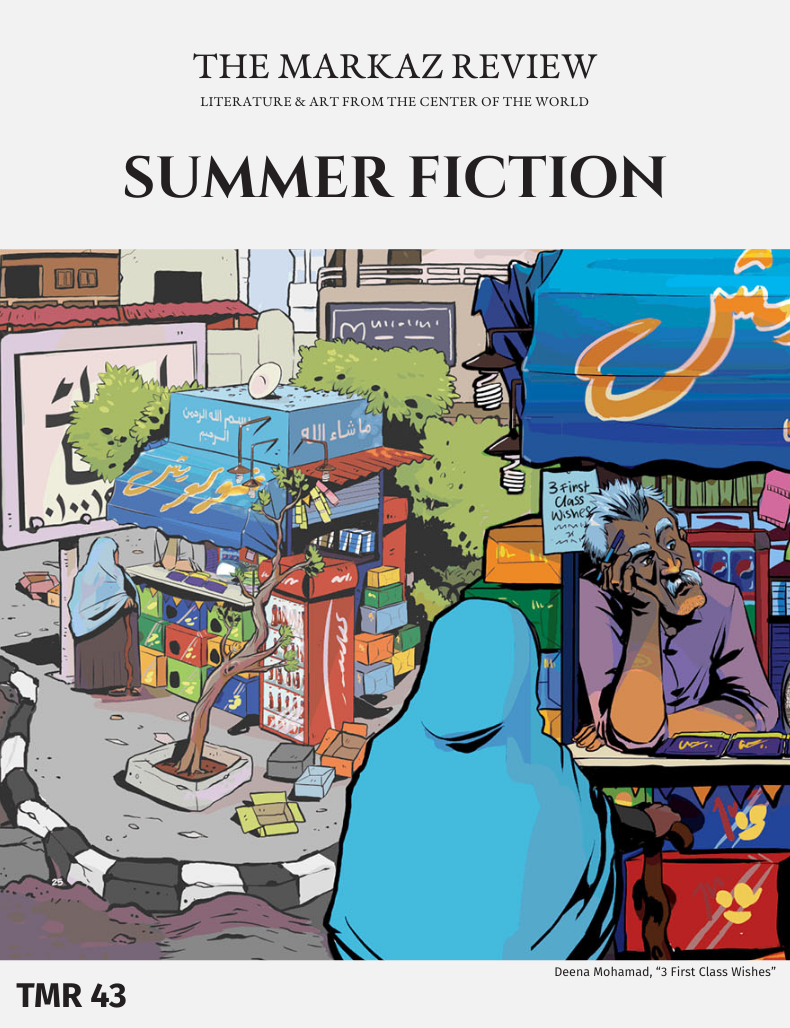

At the helm of these protests were mainly young Iranian women and Gen Z. Sixteen-year-old Nika Shakarami was one of them.

In some of the now-iconic photographs and videos from September 20, 2022, Nika can be seen, having taken her scarf off and holding it high while the scarf is in flames burning. With the united presence of their bodies in the streets, Nika and many others fiercely raised their voices to demonstrate their right to their bodily autonomy, to a normal life, to a better future. A few hours after these images were taken, Nika went missing. Her family began looking for her but were unable to trace her whereabouts. Several days later, they were told by the authorities to come in, identify, and receive Nika’s dead body.

Meanwhile, the regime officials fabricated various scenarios to absolve them from having any role in Nika’s murder; they announced that she had never been arrested and that she had committed suicide. They released a video showing a young woman dressed similarly to Nika, going into a building. The video included a clip of a slip of the body of a young woman on the pavement as though she had jumped from the roof of the building.

From the very beginning of Nika’s disappearance, family members, journalists, and human rights organizations, among others, questioned the official narrative and pointed out significant contradictions and inaccuracies. In April 2024, a comprehensive report published by the BBC, based on a leaked IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) secret report, shed new light on the final hours of Nika’s life, and her brutal killing. During the protest, in which Nika stood in front of a crowd and burned her hijab, regime agents had spied on her. She was arrested soon after the protest, and was molested by her captors while held captive and driven around Tehran in an unidentified van. She fought valiantly against the men, and was subsequently beaten to death. Her body was discarded in the streets.

The day Nika was forcibly disappeared, her aunt, Atash Shakarami posted on her Instagram account and asked people to help to find her niece. Atash is an artist with whom Nika had been living. On October 2, Atash was detained by the authorities because she had spoken out about the suspicious circumstances surrounding Nika’s death. She was released several days later, but only after she and Nika’s uncle were forced to give false televised confessions. Only later was it reported that the Shakarami family had been threatened with death if the confessions were not forthcoming. Atash remains under surveillance.

Despite all, Atash Shakarami has continued to use her posts on Instagram to bear witness, in documenting both a personal as well as a collective history of the Woman Life Freedom movement. Her writings in the form of diaries provide a complex, double-layered narrative, first, of Nika’s life as a victim of regime brutality, and second, of Atrash’s own life as a survivor of state horror. It is an interwoven biography of two Iranian women, related by blood, from two different generations, each fearlessly standing against a totalitarian regime in their own way.

The project Mourning Diaries, from which the following entries have been selected, is a collection of Atash’s writing since that dreadful day in September 2022 when Nika left home to join other young people in the streets of Tehran. Nika never again returned. Atash’s words offer us a rare intimate glimpse into Nika’s life before she became, in death, an icon of the WLF movement. They also present us with a picture of not only the immediate shock but also the long-term aftermath of loss: what it means to live through pain and to mourn, while staying strong enough to feel and think critically, to resist, and to bring all that such an experience entails to the realm of language.

October 1, 2022

Today was supposed to be your birthday.

Tenth of Mehr / First of October.

Your seventeenth birthday, our beautiful Joojoo.

But on this tenth of Mehr, your delicate and wounded body will set out on the road toward your motherland so that you can rest forever in the slopes of Zagros mountains.

On Saturday the ninth of Mehr, we receive Nika’s body.

On Sunday the tenth of Mehr, we transport her body west to Khorram Abad city.

And

On Monday afternoon, we are going to bury her in Khorram Abad’s Salehein Cemetery.

You are all invited to Nika’s final birthday.

Nika who is not anymore and is forever.

May thousands and thousands of other brave Nikas come to life from the death of our brave Nika.

October 9, 2022

Time goes on.

Life does not end.

But we will never be the people we were before Nika’s death. Something has been destroyed in us and something has risen from the ruins.

And part of that thing rising is the deep sympathy and connection our nation showed our family in the face of Nika’s painful loss.

You took our hands. And you recognized our beautiful brave Nika as the daughter of Iran. You mourned her loss and stood with us.

We are grateful.

We are grateful with our whole hearts, pained and sorrowful, and know that what you have given us and continue to give us is big enough to hold us up.

We continue to keep righteousness and beauty alive, because we know too well that if we remove these two from life, life is not worth the suffering.

Nika’s beautiful brave soul will rest in that ancient, far away cemetery, because when she left us, she was brave and beautiful, and beauty never dies and braveness is one and the same with beauty.

* I know you have been worried about me.

If I say I’m well, I’d be insulting my suffering and what I’ve lived through.

I’m not well.

I’ll never be well.

But I’m alive. I’m physically healthy. And I’m in my own house.

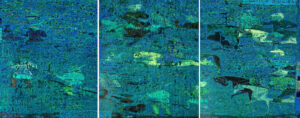

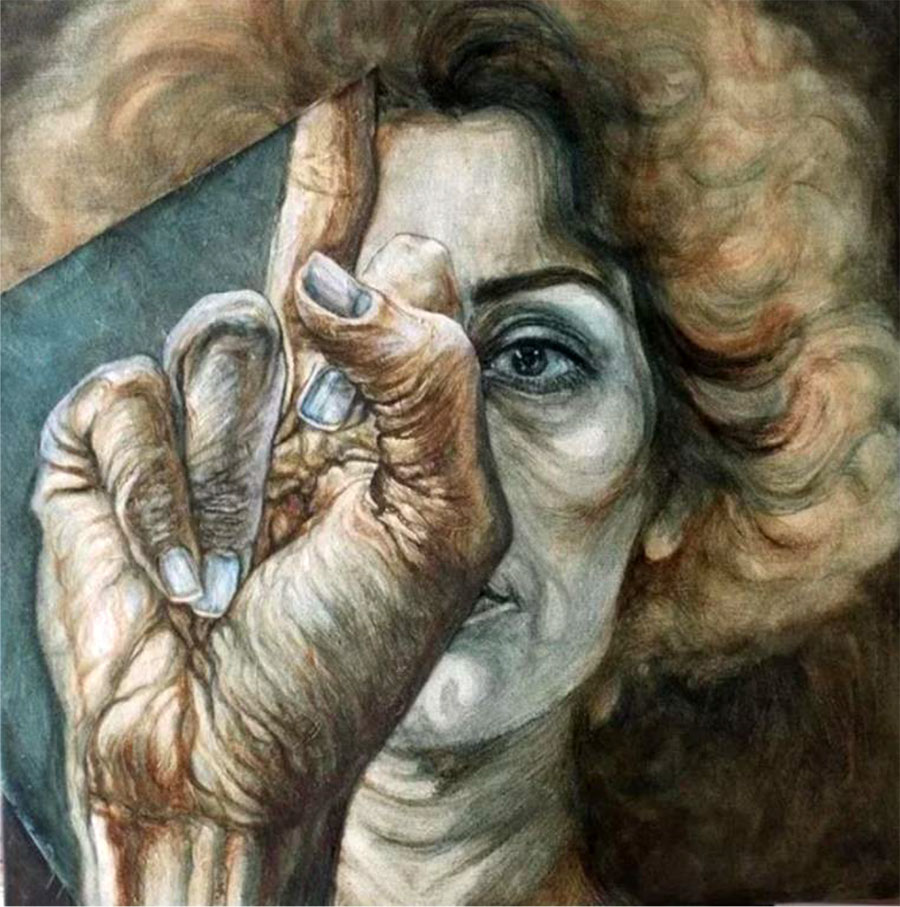

* The third picture is of Nika in my Bones exhibition. An exhibition inspired by the Zagros mountains on fire. And now she too is resting in the beautiful foothills of Zagros.

October 12, 2022

I kiss a mirage and water boils in me.

I kiss a mirage and light shines through my bones.

I kiss a mirage.

But no, no flower grows from my wounds.

Humpback whales wash up along my shores,

And the dark sun rises from my eastern lung.

Today, on the 20th of Mehr/ 12th of October, I turned forty-two.

Being born onto this earth is not a blessed event.

March 10, 2023

One half of this black cotton scarf Nika set on fire while standing on top of the trash can, and the other half remained with me, Atash, forever.

She liked wearing light-weight pieces of clothing.

As if she was always ready to run.

Even when she walked, she seemed to be in a rush.

Towards the end, I could sense her rushing somewhere and this caused me to worry intuitively. She was growing up, becoming independent.

She was growing up.

And every time I reach this phrase, this “growing up,” I feel my heart coming to a stop for a few moments, then beginning to pound faster against the walls of my chest, feeling like it’s set on fire.

No.

Nika did not grow up.

But she did grow and become mature, while she was still young in age.

She did grow, grow big and shining, turning into a star at the peak of this “blood sprouting” land.

First image text: I had bought her a bundle of simple hair elastics, and the one she is wearing here was one of the last ones from the pack … The loose black shirt, we had bought together, and she considered it her most comfortable piece of clothing … That scarf too, we had bought together. It was too wide. I cut it into half and sewed the borders again … I still have the other half … She planned to use the second half when the first one got ragged … I cut the scarf in half because the lighter and smaller this forced hijab, the better for her … When she left that day, she put on her eyeliner, put on her black mask, wore her lightest most comfortable clothes … And I did not know why she wore such light clothes … And her clothes were never returned to us … Nika who was so full of life … Nika, the bravehearted and the light-footed, left … with her small backpack and towel, with her water bottle …

She had bought those white, light shoes on sale.

You, with your courageous heart, with your feeble feet …

March 11, 2023

In the dailiness of life, objects are important, in the sense that they facilitate the life of the day. You buy shoes because you have to wear something to cover your feet to be able to walk without a risk of hurting your feet; you buy a lidded container because you want to keep your candies fresh; and you buy a key chain to put your house, car, and office keys on a ring to make sure you do not lose them.

In the dailiness of life, objects have ordinary functional meanings.

But death changes these meanings.

Death pushes these functional meanings away and creates new meanings because the person to whom the objects belong is not alive anymore to wear her shoes; to put her hand inside the wide-mouthed container, pull out a mint candy and put it in her mouth, and feel refreshed from its strong cooling taste; to turn the key in the keyhole and playfully say, “Hi auntie, it smells great in here, and I’m so hungry!”

In death, objects become important in some other sense.

Objects change their functionality with death.

You have replaced the mint candies in the candy container with two flowers you have brought from Nika’s grave and you watch them gradually decay. Later, you find one hair strand in the unused half scarf left behind by her and you add the hair to the flowers in the container.

Sometimes you place the container on your wet cheeks, and your muffled cries break the silence of the house with their waves of pain. In bed at night, you hold the bunny key ring in your fist and think about the white shoes that were never returned to you, and you whisper, “My dear Joojoo, forgive this cruel world. May your pains all be mine. You forgive, but I … I won’t.”