Beleaguered and beset by military occupation, bombardment, extremist settlers and movement-restricting apartheid, Palestine continues to harvest grapes and produce wine against all odds.

It was a good land, called Yaa Figs were in it, and grapes

It had more wine than water

Abundant was its honey, plentiful its oil.

—From “The story of Sinuhe the Egyptian” (1950 BC)

Wine, the story of wines and winemaking is a powerful connector of people. A millennia-old craft that is always evolving within the realms of cuisine and of spiritual practice, often unknown, many times celebrated, is an art elevated in the setting of restaurants and in the majesty of ritual celebrations.

Historic Palestine has been, for thousands of years, a fertile agricultural land, a space of spirituality, and the place where wine was born and celebrated.

When our paths crossed at his London restaurant, Akub, Fadi and I decided to combine our knowledge and passion for wine, our positionality for facilitating the under-represented and our voices for a humanist world in embarking on this journey of sharing Palestinian wines and spirits. I brought my craft, knowledge and practice of sommelerie, a deep-rooted understanding of winemaking and wines, while Fadi contributed his enduring relationships with Palestinian winemakers and his persistent drive to tell the story of Palestinian terroirs. With the support of many great people at Akub in London, at Louf in Toronto, and with all the pop-ups we are invited to do in Geneva, Oslo, Amsterdam, the Emirates, we always feel humbled and grateful for the food, wines and spirits from Palestine we present to the guests. Often, we are met with a great deal of interest from diners who are fascinated to experience both Palestinian food and Palestinian wines and spirits for the first time.

In the oldest continuously inhabited town in the world, Jericho (Ariha in Arabic), named after the Caananite moon god, Yarikh, the Natufians planted grapevines between 9500 and 9000 BCE. The beginning of grapevine cultivation in Jericho can also be attributed to the environmental conditions of the time, characterized by the presence of fertile alluvial soils and an abundance of water springs that provided the necessary irrigation for the vine to flourish. There have been discoveries of wine from Canaan in the ancient Egyptian city of Abydos, and specifically in the royal Umm el-Qa’ab tombs.

During the Roman and Byzantine periods, wine was produced in Palestine and exported to Syria and Egypt as documented in the “Expositio totius mundi et gentium” (anonymous author, 350/362 AD). Wine from Askalan and Gaza were exported even further afield, around the fifth century, and amphorae were found in Cyprus, Greece and beyond (Spain, Naples, Carthage, Gaul and Wales).

During the Islamic and Crusader times, the production of wine continued in Palestine, at some periods only to serve the Palestinian Christian and Jewish inhabitants and at other periods to export “Holy Land” wines to be used in churches in Europe.

In the late 1800s, some foreign monasteries established wineries on church land and bought grapes from neighboring Palestinian farmers. Wineries established in this period and still functioning today include the Cremisan Monastery near Bethlehem, where Italian Salesian monks have been making wine since 1885 and the French Trappist monks in Latrun Monastery, which began winemaking in 1899.

Today, grapevines are the second most cultivated crop in Palestine, after olive trees. Most of the grapes are intended for consumption while some parcels are used for wine and arak making. Palestine is home to 23 indigenous grape varietals and also cultivates many international ones including Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Sauvignon Blanc, and Chardonnay, among others.

Recent years have seen the emergence of various wineries, among them Taybeh, Ashkar, Jascala, Domaine Kassis, Philokalia, Julia, and many producers of arak. In this article we will look closer at Taybeh, Ashkar, Jascala, Domaine Kassis and Muaddi Artisanal Distillery.

When we taste wines and spirits, we have two very different approaches. We conduct a very rigorous tasting process. I (Anna), am often telling Fadi off for having smoked a cigarette before the tasting, while Fadi insists he can smell or taste some rare Palestinian herb or fruit infusing the wine which leads to moments of hilarity — so while Anna writes her notes, I (Fadi) call up the winemaker to find out if, by chance, quince was planted in the land next door.

Wine tasting between a sommelier and a chef is an exercise in thinking about pairings, food textures, wine textures, but most importantly, it involves thinking about the land and the people who make those wines and spirits possible.

On a hilltop, overlooking the deserts of the Jordan Valley, in a small village, Taybeh, the Khoury family members tell a story of resilience and passion for the land. The family returned from the U.S. at the start of the so-called peace process in the ‘90s, with a dream to create a brewery in Palestine. A dream in which they succeeded — not only through introducing a beautiful array of beers but by also expanding to create a winery. We often say that wineries and wines mirror the character of the winemaker. Canaan Khoury appears to be a meticulous and precise man, and his family’s winery and wines truly embody that narrative.

The grapes used to make different wines of the Nadim, come from various regions across Palestine. The local grape varieties, Zeini and Beituni, come from Hebron, villages around Taybeh like Mazra’a al Sharkiyeh, and from Beit Duqoo, close to Ramallah. The international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, and Sauvignon Blanc hail from Aboud, Birzeit, and Taybeh. Most of the soil there is Terra Rossa clay on limestone bedrocks.

In Taybeh, the volcanic ash soils packed with pebbles, along with the scorching weather in July and August, and an elevation of over 850 meters above sea level, create a distinctive set of conditions. Furthermore, the location on the brink of the red soils, just before the start of the denivelation of the Jordan valley’s desert hills, exhibits a wide diurnal temperature throughout the day, with high humidity at night and dry weather during the day.

A few weeks ago Fadi arrived in London from Palestine with a small bottle, simply marked with a hand-written label. It was a sweet wine, made by Canaan in 2015 which I had tasted with him six years ago. A long nine years later, it has made its way to London for its first official tasting. Sometimes these one-off trials that come out of curiosity or experimentation can be tricky to classify. Captivating notes of black cherry compote, dried figs, dark chocolate and a touch of sweet spice give this wine a feel of opulence. Lively acidity and delicate tannins frame and lift the palate leaving you eager for a next sip. At only just over a hundred half-bottles in existence, it is a rare vintage. The obvious pairing with Fadi’s Dead Sea Chocolate Cake is something we both approve of.

A bit further north is the village of Bir Zeit ( “oil well” in Arabic). Situated 800 meters above sea level, Bir Zeit boasts iron-rich terra rossa soil intermingled with patches of ancient volcanic limestone, varying in depth from deep to very shallow, depending on the specific parcel. That is an ideal terroir for growing olive trees, citrus fruit, figs, pomegranate, mulberry, and grapes.

The Kassis family started planting the land with grapevines in 1998. A few years later, in 2004, they made their first wines and by 2017 Adam, who currently runs the winery, joined the family business. Adam dreams of making his family winery a space for the discovery of Palestinian wines, tradition, and history. Recently he restored an old home and is hosting educational visits and events.

The main focus is placed here both on local varieties such as Daboukki and Jandali, and international varieties such as Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon.

The fresh, mineral character of the Dabouki/Jandali blend sets the tone for the house style of white wines made by Adam. Refreshing notes of barkouk (local green plum), crunchy green apple, gooseberry and lime zest with tingling minerality pairs deliciously with maftoul, the hand-rolled grain, a recurrent staple in Fadi’s menus.

Up north, near the Lebanese border, the Ashkar family has ties to the lands around the village of Iqrit that go back generations, with a centuries-long farming history. They have revived this relationship that had been severed during the Nakba in 1948*. The village press in Iqrit was used for locally-grown olives and grapes, gathering the farmers around these festive seasons or mawasem in Arabic. The seasonal rhythm of life came to an end on October 31, 1948, when the Israeli army expelled the population of Iqrit and subsequently destroyed the village to prevent anyone from returning. The sole surviving building is the Greek Catholic church.

Every Ashkar label carries a painting commemorating Iqrit and and the names of some wines represent the original names of specific pieces of land in the region.

The old vines surrounding the village ruins supply grapes to produce Do’er, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Shiraz, as well as the reserve wines that are made only in prime years. The soil of Iqrit is a combination of terra rosa, limestone, and alluvial soils. The Merlot in that region is quite unique because as it is subtly tainted by the ladybugs (Um Ali) present in the area, which imparts herbaceous and green bell pepper flavors to the wines, adding to their complexity.

The rest of the vineyards are located in multiple areas around the Galilee, which of course is one of the regions of Palestine that was occupied during the 1948 Nakba, in which Zionist attacks forced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to flee, and hundreds of villages and towns were emptied of their inhabitants. After living under martial law for 20 years, some Palestinians chose to remain in their homeland and became known as ’48 Palestinians; they eventually obtained Israeli citizenship.

In the last 76 years there has been an ongoing policy of trying to erase Palestinian culture, with an expansive use of the term Arab to substitute the term Palestinians, in reference to ethnicity, along with Israel’s systematic treatment of ’48 Palestinians as second class citizens, particularly with state services being withheld or whittled down in comparison to the Israeli citizens of other origins. Even though they have access to services and freedom of movement compared to other Palestinians in the West Bank or Gaza, the Palestinians of 1948 in Israel face a daily struggle. They are constantly trying to preserve their identity while navigating a system that, at its core, is designed to reshape their narrative and is rooted in colonialism.

The general region of Galilee is a typical Mediterranean terroir, with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. The Shiraz and Petit Verdot grapes come from a vineyard near Deir el Assad, a town in the Lower Galilee where the soil is predominantly Terra Rosa. The vineyard is situated deep in the valley which provides essential shade for the grapes, helping it cope with the excessive summers. However, the Upper Galilee vineyards of Bayad contribute to the wine’s rich mineral characteristics and help maintain its acidity. At an altitude of approximately 600-700 meters above sea level, a significant portion of the Cabernet Sauvignon is sourced from there.

A bit further to the west, lies the village of al-Jish. The Khreish family named their winery after the Roman village, Jascala. The wines of Jascala are as full of personality as its two founders, Richard, the winemaker, and his brother, Nasr, who looks after the vineyards. Located in the Upper Galilee where all their grapes come from, the vineyards are planted on Jabal Jarmaq with Terra Rossa soils on the bedrock of limestone and 33 dunams of land at altitudes from 846 —776 meters above sea level and a denivelation that extends from east to west. The excellent aeration renders any humidity-related problems, like fungus, virtually non-existent.

Some vineyard terraces have up to four different grape varieties planted. There is no use of herbicides or insecticides and all the harvest is hand-picked. Neighboring lands are planted with nectarines, apples, and cherries, which according to Fadi, all influence the taste of wines.

Aida was one of the wines that immediately stood out for both of us. Named after Mama Aida and only produced in exceptional years, this wine carries opulent notes of ripe damson fruit and black currant marmalade, complemented by toasty notes of tobacco leaf, dark liquorice, and fenugreek. It finishes with a pleasant touch of fresh black pepper. The Aida wine is a perfect match with braised goat cooked in sage and zaatar.

The Muaddi Distillery is famous for its small batch artisan arak production. Based in Bethlehem, Nader is using grapes sourced from local villages like Beit Jala, Al Khader, Shuyukh, Al-Arrub, Beit Ummar, and Halhoul. The white baladi varietal, Dabouki, is used for base wine that is then distilled in the alembic pot stills. This process was invented by Jabr Bin Hayan, a scholar and alchemist from Baghdad in the 10th century. The triple distillation and flavoring with indigenous aniseed, as well as the use of excellent water from the Ein Ad-Duyuk spring, north of Jericho, for proofing, creates the smoothness of this arak. It is the perfect accompaniment for a jam’a (gathering of friends or family), soulful conversations over turmos (lupin beans), grilled sea bass in Yaffa, or even during a solitary, nostalgic drinking session, much like the one Ghawar Al-Tosheh has in the Syrian play Kassak ya watan, in which the actor reflects on the state of affairs in the Arab world.

Wine is intrinsically linked to the land through the grapevines, the terroir, the winemakers, and their families. In Palestine, unlike other wine-making regions, the wine industry and grapevine farming have been targeted by the occupation’s efforts to control the narrative and seize the land to destroy the crops.

In historical context, biblical texts underscore the significance of land and crop control. The Israelites sent 12 spies to the Land of Canaan (modern-day Palestine) to observe before going into battle. And guess which fruit the spies brought back? Grapes!

“What is the soil like, is it fat or lean? Are there any trees in it or not? You shall be courageous and take from the fruit of the land.” It was the season when the first grapes begin to ripen.”

“They cut off a branch with only one bunch of grapes on it. They carried it on a pole between two of them. They also brought some pomegranates and figs.”

—From The Book of Numbers, 13

Throughout history, different groups have constantly fought over land ownership and the narratives associated with it. In colonial contexts, these groups often create narratives to establish their own link to the land while discrediting the indigenous populations’ connection.

Palestinian farmers have been subjected to intentional destruction of their arable lands in many ways. One method involves the construction of “bypass” roads, which connect Israeli cities to illegal Israeli settlements in the West Bank. These roads pass through Palestinian lands and are encircled by a “security perimeter,” effectively seizing the surrounding area. South of Bethlehem, these roads intersect with the vineyards of Palestinian villages such as Al-Khader, Khirbet Zkaria, Halhul, and the northern region of Hebron. Another method of farmland destruction takes place when settlers destroy grapevines, olive trees, and other crops. They vandalize the fields, setting fire to hundreds of meters of trees, or intimidate and chase Palestinian farmers off their own land.

Theft of the narrative occurs when Israeli wineries in the settlements, built on confiscated land, export produce with misleading labels to consumers worldwide. It’s quite odd that in a world where wine enthusiasts place great value on origin, appellation, history, and tradition, there seems to be a deliberate oversight when it comes to the history of winemaking in Palestine. We are grateful that there are still resilient winemakers today in Palestine, supporting the farmers, producing wines and spirits that not only pair beautifully with Palestinian cuisine but reflect the terroirs of Palestine and the millennia-old stories of this craft.

*Palestinians were dispersed from Iqrit in 1948. Ever after, the only place the original inhabitants have been allowed to use is the church. Since October 7, 2023, Iqrit, like most of the borderlands, has found itself situated between Hezbollah and Israeli shelling.

** Our selection of Palestinian wines, spirits, and beer can be found in Akub, London and Louf, in Toronto. If you are in a city where Fadi and Anna are hosting a pop-up, make sure to reach out as we always pair the foods and wines from Palestine. Today, some wineries’ products can be found online or at Palestinian restaurants in the U.S. and Europe.

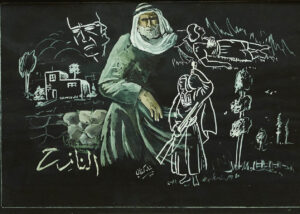

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)