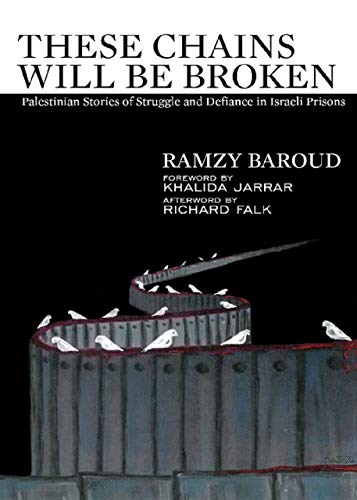

The following text by Khalida Jarrar, who argues one can “fashion hope out of despair,” first appeared in These Chains Will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons, edited by Ramzy Baroud (Clarity Press, 2019).

Ramzy Baroud

Khalida Jarrar was born in the city of Nablus in the northern West Bank on February 9, 1963. She has a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration and a Master’s degree in Democracy and Human Rights from Birzeit University. She served as a Director of Addameer Prisoners’ Support and Human Rights Association from 1994 to 2006, when she was elected to the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC)—the Palestinian Parliament. She now heads the PLC’s Prisoners Commission, in addition to her role on the Palestinian National Committee for follow-up with the International Criminal Court.

Khalida Jarrar’s high profile as a Palestinian leader dedicated to exposing Israeli war crimes to international institutions has made her a target of frequent Israeli arrests and administrative detentions. She has been arrested several times, first in 1989, on the occasion of International Women’s Day. She spent a month in prison for taking part in the March 8 rally.

In 2015, she was detained in a pre-dawn raid by Israeli occupation soldiers, who stormed her house in Ramallah. Initially, she was held in administrative detention without trial but, following an international outcry, Israeli authorities tried Khalida Jarrar in a military court, where 12 charges, based entirely on her political activities, were made against her. Some of the charges included giving speeches, holding vigils and expressing support for Palestinian detainees and their families. She spent 15 months in prison.

Khalida Jarrar was released in June 2016, only to be arrested again in July 2017, when she was also held under administrative detention. The Israeli raid on her home was particularly violent, as soldiers destroyed the main door of her house and confiscated various equipment, including an iPad and her mobile phone. She was interrogated at Ofer Prison before being transferred to HaSharon Prison, where many Palestinian female prisoners are held. She was released in February 2019, after spending nearly 20 months in prison.

Once more, Khalida Jarrar was arrested from her home in Ramallah on October 31, 2019. During her latest imprisonment, one of her two daughters, Suha, passed away at the age of 31. Despite an international campaign to allow Khalida to attend her daughter’s funeral on July 13, 2021, the Israeli government rejected all appeals. However, a letter by Khalida was smuggled out of prison to serve as a farewell to Suha. In the letter, she wrote:

“Suha, my precious.

They have stripped me from bidding you a final goodbye kiss.

I bid you farewell with a flower.

Your absence is searingly painful, excruciatingly painful.

But I remain steadfast and strong,

Like the mountains of beloved Palestine.”

Khalida Jarrar is one of many examples where Palestinian resisters have taken their steadfastness (sumud) and resistance with them inside Israeli prisons, finding opportunities to fight back, despite their confinement, despite the physical pain and the psychological torture. Moreover, instead of seeing prison as a forced confinement, Khalida Jarrar has used it as an opportunity to educate and empower her fellow female prisoners. In fact, her achievements in prison changed the face of the Palestinian female prisoners’ movement.

Khalida Jarrar

Prison is not just a place made of high walls, barbed wire and small, suffocating cells with heavy iron doors. It is not just a place that is defined by the clanking sound of metal; indeed, the screeching or slamming of metal is the most common sound you will hear in prisons, whenever heavy doors are shut, when heavy beds or cupboards are moved, when handcuffs are locked in position or loosened. Even the bosta—the notorious vehicles that transport prisoners from one prison facility to another—are metal beasts, their interior, their exterior, even their doors and built-in shackles.

No, prison is more than all of this. It is also stories of real people, daily suffering and struggles against the prison guards and administration. Prison is a moral position that must be made daily, and can never be put behind you.

Prison is comrades—sisters and brothers who, with time, grow closer to you than your own family. It is common agony, pain, sadness and, despite everything, also joy at times. In prison, we challenge the abusive prison guard together, with the same will and determination to break him so that he does not break us. This struggle is unending and is manifested in every possible form, from the simple act of refusing our meals, to confining ourselves to our rooms, to the most physically and physiologically strenuous of all efforts, the open hunger strike. These are but some of the tools which Palestinian prisoners use to fight for, and earn, their very basic rights and to preserve some of their dignity.

Prison is the art of exploring possibilities; it is a school that trains you to solve daily challenges using the simplest and most creative means, whether it be food preparation, mending old clothes or finding common ground so that we may all endure and survive together.

In prison, we must become aware of time, because if we do not, it will stand still. So, we do everything we can to fight the routine, to take every opportunity to celebrate and to commemorate every important occasion in our lives, personal or collective.

The individual stories of Palestinian prisoners are a representation of something much larger, as all Palestinians experience imprisonment in its various forms on a daily basis. Moreover, the narrative of a Palestinian prisoner is not a fleeting experience that only concerns the person who has lived it, but an event that shakes to the very core the prisoner, her comrades, her family and her entire community. Each story represents a creative interpretation of a life lived, despite all the hardship, by a person whose heart beats with the love of her homeland and the longing for her precious freedom.

Each individual narrative is also a defining moment, a conflict between the will of the prison guard and all that he represents, and the will of the prisoners and what they represent as a collective—capable, when united, of overcoming incredible odds. The defiance of Palestinian prisoners is also a reflection of the collective defiance and rebellious spirit of the Palestinian people, who refuse to be enslaved on their own land and who are determined to regain their freedom, with the same will and vigor carried by all triumphant, once-colonized nations.

The suffering and the human rights violations experienced by Palestinian prisoners, which run contrary to international and humanitarian law, are only one side of the prison story. The other side can only be truly understood and conveyed by those who have lived through these harrowing experiences. Quite often, missing from the story of Palestinian prisoners is the inspiring human trajectory of Palestinian men and women who have subsisted through defining moments, with all of their painful details and challenges.

Only by delving deeper into the prisoners’ narrative, can you begin to imagine what it feels like to lose a loving mother while being confined to a small cell, how to deal with a broken leg, to be left without family visitation for years at a time, to be denied your right to education and to cope with the death of a comrade.

While it is important that you must comprehend the suffering endured by prisoners, such as the numerous acts of physical torture, psychological torment and prolonged isolation, you must also realize the power of the human will, when men and women decide to fight back, to reclaim their natural rights and to embrace their humanity.

Fighting back can take on many forms. Throughout the various stints of imprisonment as a political prisoner in Israeli jails, I, too, took part in the various forms of resistance within the walls of the prison. For me, education for Palestinian female prisoners became an urgent priority.

Female prisoners in Israeli prisons are treated somewhat differently than males, not only in terms of the nature of the violations committed against them, but also in the degree of their isolation. Since there are far fewer female prisoners than males, it is easier for Israeli prison authorities to isolate them completely from the rest of the world. Moreover, there are only a few women prisoners with university degrees; the level of education among these women is alarmingly low.

I was already aware of these facts when I was detained by Israel in 2015, spending most of my detention in HaSharon Prison. Therefore, I decided to make it my mission to focus on the issue of education for women who were denied the opportunity to finish school, whether as children or those who were denied such a right due to difficult social conditions. The idea quickly occupied my mind: if I could only help a few women achieve their high school diplomas, I would have made good use of my time in detention. These diplomas would allow them to pursue university degrees as soon as they were able to and, eventually, achieve a level of economic independence. More importantly, armed with a strong education, these women could contribute even more to the empowerment of Palestinian communities.

However, there are plenty of obstacles facing all prisoners, especially women. Israeli prison authorities place numerous restrictions on prisoners who want to pursue formal education. Even when the Israel Prison Service (IPS) agrees, in principle, to grant such a right, they ensure all practical conditions required to facilitate the work are missing, including the availability of classrooms, blackboards, school supplies and qualified teachers.

The latter obstacle, however, was overcome by the fact that I have a Master’s degree, which qualifies me from the viewpoint of the Palestinian Ministry of Education to serve as a teacher and to supervise final high school exams, known as Tawjihi. Just seeing the excitement on the faces of the girls when I floated the idea by them inspired me to take on the daunting task, the first such initiative in the history of Palestinian women prisoners in Israeli jails.

I began by contacting the Ministry of Education in order to fully understand their rules and expectations, and how they would apply to female prisoners who want to study for their final exams. My first cohort of students consisted of five women, who so giddily took on the challenge.

At that early stage, the prison administration was not fully aware of the nature of our “operation,” so their restrictions were merely technical and administrative. The experience was, in fact, new to all of us, especially to me. I must admit that I may have exaggerated my expectations in my attempt to ensure a high degree of academic professionalism in conducting my classes and the final exam. I just wanted to make sure that I did not, in any way, violate my principles, because I truly wanted the girls to earn their certificates and expect more of themselves.

We had few school supplies. In fact, each class had to share a single textbook that was left by Palestinian child prisoners before they were transferred by IPS to another facility. We copied the few textbooks by hand; this way, several students were able to follow the lessons at the same time. My students studied hard. A single class would, at times, extend to several hours, which meant that they would willingly lose their only break for the day when they were allowed to leave their cells. We had so much to cover and so little time. In the end, five students took the exam, results of which were sent to the Ministry of Education to be confirmed. Weeks later, the results came back. Two of the students passed.

It was an extraordinary moment. The news that two students had earned their certificates while in prison spread quickly among all the prisoners, their families and organizations that champion detainee rights. The girls celebrated the news, and all of their comrades felt truly happy for them. In no time, we mobilized again, getting ready to produce yet another cohort of graduates. However, the more media attention our achievement garnered, the more worried the Israeli prison authorities became. I was not at all surprised that the IPS decided to make it difficult for the second group, also consisting of five students, to go through the same experience.

It was a real battle, but we had every intention of fighting it to the end, no matter the pressure. The prison administration informed me officially that I was no longer allowed to teach the prisoners. They harassed me repeatedly, threatening to send me to solitary confinement. But I know international law well, and I repeatedly confronted the Israelis with the fact that I understood the rights of the prisoners and had no plans to back down. Despite all of this, I managed to teach the second group of girls, preparing the exams myself, in coordination with the Ministry of Education. This time, all five students who took the exam passed. It was a great triumph.

After what we achieved, I realized that there is a need to institutionalize the educational experience for female prisoners, and not to tie it to me or to any single person. For this to succeed in the long term, it needed to be a collective effort, a mission to be championed by every group of women in prison, for years to come. I placed much of my focus on training qualified female prisoners, by getting them involved in teaching and by familiarizing them with administrative work required by the Ministry of Education. I set up the apparatus to ensure a smooth transition for the third group of graduates, as I was anticipating my imminent release.

I was freed in June 2016. Although I returned to my regular life and professional work, I never ceased thinking about my comrades in prison, their daily struggles and challenges, especially those who were keen on getting the education that they need and deserve. I was thrilled when I learned that two female prisoners took on the final exams after I left, and successfully graduated. I felt as happy as I did when I was freed and reunited with my family. I was also relieved to learn that the system I put in place before my release was working. This gave me much hope for the future.

In July 2017, the Israeli military arrested me again, this time for 20 months. I returned to the same HaSharon Prison. There were many more female prisoners than before. Immediately, with the help of other qualified prisoners, we began preparing for the fourth group to graduate. This time, nine female prisoners were studying for the exam. There were more volunteer teachers and administrators. The prison had suddenly bloomed, turning into a place of learning and empowerment.

The prison administration went crazy! They accused me of incitement and began a series of retaliatory measures to shut down the whole schooling process. We accepted the challenge. When they closed our classroom, we went on strike. When they confiscated our pens and pencils, we used crayons instead. When they hauled away our blackboard, we unhooked a window and wrote on it. We smuggled it from one room to another, during the times that we had designated for learning. The prison guards tried every trick in the book to prevent us from our right to education. To show our determination to defeat the prison authorities, we named the fourth group “The Cohort of Defiance”. In the end, our will proved mightier than their injustice. We completed the entire process. All the girls who took the final exam passed with flying colors.

I cannot describe to you in mere words how we felt during those days. It was a huge victory. We decorated the prison walls and celebrated. We were all happy, smiling and jubilant because of what we managed to achieve together, when we stood united against the unfair rules of Israel and its prison administration. The news spread beyond the prison walls and celebrations were held by the families of the graduates throughout Palestine. The fifth group was the crowning of that collective achievement. It was the sweet reward following months of struggle and hardship that we had endured, while insisting on our right to education. Seven more students are now studying for the final exam, in the hope of joining the other 18 female graduates who obtained their certificates since the first experience commenced in 2015.

The aspirations of female prisoners evolved, as they felt truly capable and empowered by the education they had received, especially as they had endured so much to obtain what should be a basic human right for all. Those who have obtained their Tawjihi certificates are ready to progress to a higher level of education. However, since the Ministry of Education is not yet prepared for this step, the prisoners are creating temporary alternatives.

Since I have a Master’s degree in Democracy and Human Rights, and also have lengthy experience in this field through my work with Addameer and the PLC, among other institutions, I offered my students a training course in International and Humanitarian Law. To teach the course, I managed to bring into prison some of the most important and relevant texts pertaining to international treaties on human rights, including the Arabic translation of all four Geneva Conventions. Some of these documents were brought in by the Red Cross, others by family members who came to visit me in prison.

Forty-nine female prisoners participated in the course, which was divided into several periods, each consisting of two months. At the end of the course, the participants received certificates for having completed 36 hours of training in International and Humanitarian Law, the results of which were confirmed by several Palestinian ministries. While we celebrated in prison, a large ceremony sponsored by the Ministry of Prisoners’ Affairs was held outside, where the families and some of the freed prisoners attended, amid a huge celebration.

In the end, we did more than fashion hope out of despair. We also evolved in our narrative, in the way we perceive ourselves, the prison and the prison guards. We defeated any lingering sense of inferiority and turned the walls of prison into an opportunity. When I saw the beautiful smiles on the faces of my students who completed their high school education in prison, I felt that my mission has been accomplished.

Hope in prison is like a flower that grows out of a stone. For us Palestinians, education is our greatest weapon. With it, we will always be victorious.

Hi, was this text written originally in English by Khalida Jarrar? or was is translated by Ramzi from Arabic. I need to know for a research project on marginalized women writing in English

Thank you.