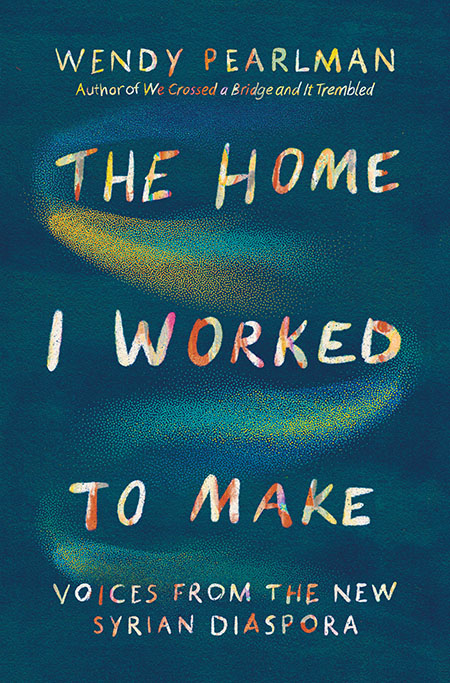

War forced millions of Syrians from their homes. It also forced them to rethink the meaning of home itself. In her new book The Home I Worked to Make: New Voices from the Syrian Diaspora (W.W. Norton 2024), Wendy Pearlman interviews 38 Syrian refugees. Kareem*, speaking in the book’s prologue, is interviewed in an undisclosed occasion.

As told to Wendy Pearlman

In my life, there are three faces that I will never forget.

One was the face of a father I met after his son died of cancer. That was the face that made me want to study medicine.

The other was my own father’s face alter they arrested my brothers.

And then there was the face of Mohammed’s mother when we learned that he had been killed.

I was in high school when the revolution began in 2011. Tunisia and then Egypt were all over the news. I would light up when I watched. We saw that people had voices and that their voices could be heard. I had always had a general sense that we were not living free lives. Then, all of a sudden, it became possible to stand up. Most people thought there was no way that something like that could happen in Syria. But a Syrian Revolution page began on Facebook and it called for a protest on March 15. My friends and I counted down: twenty days left, fifteen days left, ten days, five.

March 15 came, and I got ready for the demonstration. People were saying to bring Pepsi to combat the tear gas. I packed four cans in my backpack and pretended that I was going to school. My parents caught me and refused to let me leave the house. Like most Syrians, they were terrified that their children would get hurt.

There was another demonstration three days later, and I went. Prayers concluded in the mosque and people started chanting for freedom. l built up the courage to join, but then managed to escape when security agents charged in and started beating people. The feeling of protesting was something out of this world. lt was like someone who had lived his whole life without an achievement and then did something remarkable. Or like someone who spent six years in medical school and finally got his degree.

I met Mohammed when we started medical school together in October 2011. I was the youngest of my siblings and he was the eldest of his. He was someone who could handle responsibility. I trusted him with any problem. He was the one I sought out for advice. We were not close before we started going to demonstrations, but protesting together cemented our relationship. There is no bond like sharing that experience. We would go to school in the morning. attend lectures, and then go out and protest. Mohammed became my brother. Not a cousin or a friend, but a brother.

lt was my job to make signs. I would buy four sheets of A4 paper, tape them together, and fold them again and again until they were tiny enough to hide in my pocket. When we got to the demonstration, I would unfold the sign to its full size. I did not want to write just any slogan. I wanted to write something that inspired thought. One of my slogans became really popular: “Bitter is the taste of freedom in the mouth of slaves.”

We were eight hundred students in our first year of medical school. We slowly became divided between those who supported the regime and those who did not. After a while, separation became tension, and tension became hatred. Your political position became your identity. You couldn’t trust anyone. When you spoke with someone, your safety depended on knowing if you could trust that person or not. Knowing if this person is with the regime or opposition was not just a question of fact. lt was a necessity.

Once in chemistry lab, a regime supporter came and pounded me on the back. He accused me of putting a chemical liquid on another regime supporter. I told him that this liquid was for a particular assignment that I hadn’t even started yet. But there was nothing I could do to defend myself against him. At any point, he could report me to the National Union of Syrian Students.

The National Union of Students was a group of students, but they had power to function like a branch of the secret police inside the university.** And they saw that people were getting bolder. Mohammed and I started going to demonstrations every day. Other students were posting signs criticizing the regime or writing on desks and walls. Once there was even a protest on campus, though that was really risky. Some students formed what they called the “Union of Free Syrian Students.” lt was like an alternative to the official Students’ Union, ready to replace it when the regime fell.

The Students’ Union decided that they needed to put a stop to this. They arrested a graduate student in the faculty of dentistry. Later, we got news that he died under torture. The Free Students’ Union posted something on Facebook about him. I copied the post and pasted it on my own page. A friend sent me a Facebook message urging me to delete it, as those words were dangerous. But I had used my privacy settings to share it only with friends I trusted, so I was not afraid.

First semester exams came. The Students’ Union knew that all students would be present on campus, and this was a chance to grab whomever they wished. One of our friends was taking an exam when Students’ Union members marched into the lecture hall. They walked directly to him and took him away.

The following week there was another exam. I got on the bus to go to the university but couldn’t shake my feeling of unease. I thought about my friend who was arrested and about the student killed under torture. I decided not to go to campus.

I got off the bus and walked around, passing the time until I figured the exam was over. Then I called Mohammed to see how it went. He answered, but with none of his normal friendliness. There was no “Hello” or “How are you?” Just “Where are you?” His voice was cold and rough. I replied that I was on my way to him. But I knew that something was wrong. I kept walking and then it occurred to me: he was trying to tell me something. The tone of his voice was communicating the opposite of his words. He was telling me:

“Stay away. Stay as far away as you can.” He was telling me, “They are here. Don’t come.”

I made more calls and heard the rest from another friend. The Students’ Union had arrested Mohammed. They were with him outside the library, waiting for me to come.

That was how I learned that I was wanted. I went to an Internet café and deactivated my Facebook account. I felt like all eyes were on me. I felt like every person passing on the street was coming to arrest me. Later I got a call from an unfamiliar number. I guessed that it was someone from the Students’ Union and I didn’t answer.

The next week they arrested more students, including other friends.

The rest of us realized that they were coming for us, one by one.

Mohammed’s whereabouts remained unknown, but others who were arrested were eventually released. I spoke with them and slowly pieced together dues. The Students Union arrested the guy who had once messaged me on Facebook about my post. When they interrogated him, they opened his account and saw his message to me saying “Delete this.” From there, they entered my page and saw my reposting from the free Students’ Union. They also interrogated another arrested student, demanding to know who was in the Free Students’ Union. When he said that he didn’t know, the head of the Students’ Union brought him a sheet of paper and pen. He commanded him to write my name.

I went to Mohammed’s family after he was arrested. His mother was in such a state … I don’t have the words to describe it. I continued to call and visit them after that. His mother knew that I was Mohammed’s closest friend. When she looked at me, she seemed to see him.

Weeks passed without any news about Mohammed. His family paid tens of thousands of dollars to try to learn anything they could about where he was and how he was doing. Different people promised that they would bring information in exchange for payment, but they were all lying.

Three months went by before they finally got a call. A man who had been in prison with Mohammed was released. He told them that Mohammed had undergone terrible torture. He was at his side when Mohammed died from his injuries.

I got the news and went immediately to Mohammed’s mother. Her grief was unlike anything I’d ever witnessed. She kept crying, “Mohammed is gone. Mohammed is gone.” As I said, in my whole life there are three faces I will never forget. Hers is one of them.

No one ever came to my house to arrest me. I was only wanted at the university. In the 1980s, universities in Syria were a center of political activity. The government knew this and didn’t want it to be repeated. They wanted universities to provide zero space for opposition. They wanted universities to be silent except for a single voice: the voice of the regime.

The Students’ Union understood that if one person got killed, everyone else would learn the lesson. They needed a sacrificial lamb, and Mohammed was that lamb. I might have been one too. And that’s why I never set foot on campus again.

I tried to move on with life, but no longer saw a future. All of these questions never left me. Why should I be banned from learning? Why should I be denied my chance to become a doctor? Because I wrote something on Facebook? I started having nightmares. Every week I had at least five, and some nights I had many. They always built on the same idea: somebody was chasing me, and I was running to escape. I would wake in a panic. A few seconds would pass before I remembered; I am a wanted person. I am still being chased and am still trying to escape. The panic would linger. The feeling I lived with during the day was no different than the feeling I had in my dreams.

I stayed in Syria for another year and a half. It became a society of war and abuse. There was no place for people who simply wanted to breathe, who wanted a more open life. A society during war exists for those who know how to take advantage of war conditions for their own profit. Those are the people who win. When you live in a society at war, it changes you from the inside. lt changed me too. It’s not just the course of my life that changed. My personality and my soul also changed.

The morning I left Syria, I took the bus to the cell phone company to discontinue my number. The bus was packed, so I stood near the door. People kept coming on and off, on and off. A soldier in uniform came on, and I stepped off the bus to make room for him. He got on and motioned at me to get back in. I stood on the sidewalk for a moment. He repeated, “Come back inside.”

I looked at him and asked myself: ls this going to be my last image of Syria? A man carrying a weapon? I thought, I will leave you more than this spot on the bus. I will leave you all of Syria. I am leaving, and I leave this entire jungle to you.

* “Kareem” is a pseudonym that was chosen to protect the speaker and his family from retribution by the Assad regime. After the regime’s fall, the speaker can reveal that his real name is Mohammed. He currently is completing his medical studies in Germany.

** The National Union of Syrian Students, founded when the Baath Party seized power in Syria in 1963, has long served as the ruling party’s arm of surveillance, control, and repression inside Syrian Along with the Revolutionary Youth Union based in middle and high schools and the Baath Vanguards Organization targeting elementary schools, the Students’ Union has served as part of the apparatus through which the regime seeks to embed its rule throughout society. Since 2011, the NUSS has been accused of assisting in the torture, disappearance, and murder of thousands of university students suspected of opposing the Assad regime.