İlker Hepkaner

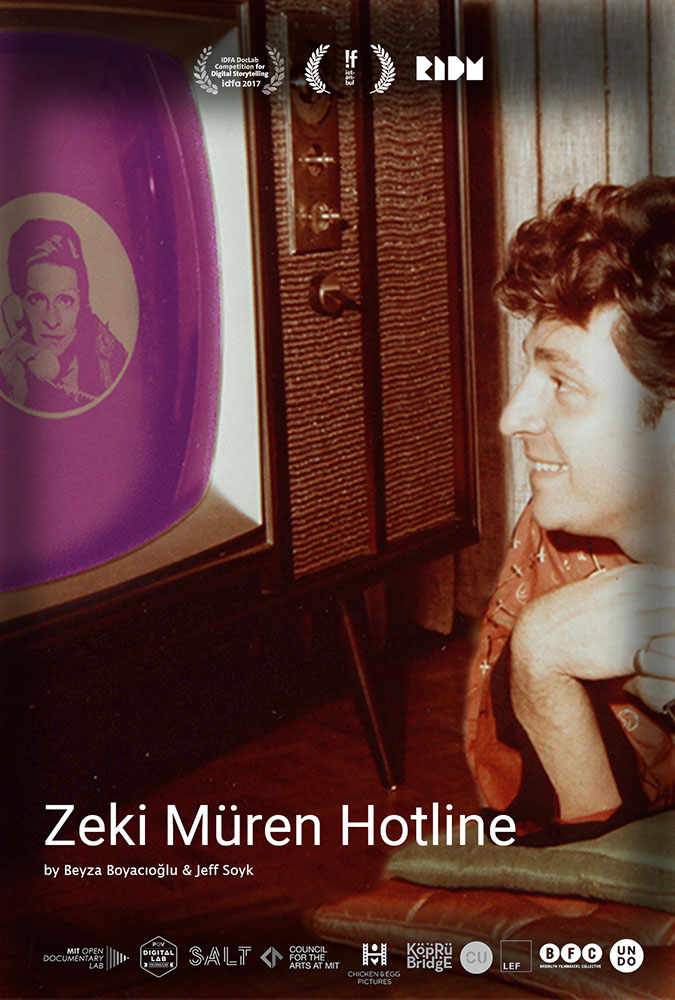

“Zeki Müren, you are the best thing that happened to us.” Leaving a voicemail on a hotline twenty years after his passing, a fan of Zeki Müren, overheard by viewers of a new documentary, expresses Turkish people’s deep love and admiration for the most popular music personality of the 20th century in Turkey. On the surface, the 2022 Webby Award Honoree Zeki Müren Hotline is a web documentary recounting the memory of Zeki Müren, who still enjoys widespread acceptance by Turkish people despite publishing a manifesto on why he wore a skirt on stage during his performances in 1970. However, Zeki Müren Hotline, which you can watch in Turkish and English, also documents how queer artists in Turkey experience fame, love, hate, and resistance.

Filmmaker and editor Beyza Boyacıoğlu directs with media artist Jeff Soyk. Boyacıoğlu started with the idea of a film, but her studies at MIT’s Comparative Media Studies program allowed her to explore a digital, interactive way of telling Müren’s life story. At the intersection of memory and technology, Zeki Müren Hotline expounds the unique and queer place the artist still holds in Turkey through sound, image, and word.

Until his death in 1996, Zeki Müren dominated the Turkish music scene while continuously blurring gender boundaries with his flamboyant looks, similar to Liberace in the US and Walter Mercado in Puerto Rico. Müren started his music career on the state radio in the early 1950s as a singer, but his creativity exceeded singing. While producing hits in the genre called “Turkish artistic music,” which encompassed classical Ottoman music traditions, he also starred in films. He designed the controversial costumes he wore on stage.

In Turkey, Zeki Müren is considered a national treasure for all his artistry, but his rise to fame could not have happened in a vacuum. He received tremendous support from the Turkish state’s cultural institutions. The state’s radio and TV platforms were wide open to him while musicians producing Arabesque — which was influenced by Egyptian and Lebanese music — faced state censorship in the 1970s. The public has given him the monikers of “Sanat Güneşi (Sun of Arts)” and “Pasha,” not only due to their nationwide love for the musician, but also because of their appreciation of his utmost respect and love for his listeners.

Müren never publicly stated his sexual and/or gender identity but lately he has been widely considered as a queer icon. Currently, in a political environment predominantly hostile to LGBTQ+ people in the country, Zeki Müren is being rediscovered for his exemplar artistry and queer expression. Through meticulous archival research and montages of his songs and imagery, Zeki Müren Hotline not only documents the extraordinary life of one of the most popular public figures in Turkey, but also shows how people have repurposed his life and fame since the late 2010s as a reaction to Turkey’s new cultural landscape, shaped by the AKP regime of almost two decades.

The neoliberal conservative AK Party’s victory in 2002 ushered in a considerable cultural change in the country. In the beginning, the AK Party (AKP) introduced legislation to advance freedom of expression as a part of Turkey’s EU bid and its agenda of crippling the military’s power over political institutions. Hence, the first years of AKP rule witnessed an extraordinary shift in the cultural sphere: voices from the periphery, such as Kurds or the religiously conservative, found more opportunities in the mainstream media and cultural discourse. The republican cultural elite, which was the urban elite as the product of Kemalist cultural policies of the Turkish state, was sidelined. The 2010 referendum bestowed upon the AKP control of the judiciary branch; it also gave the party the political tools to silence first the republican elite, and later Kurds since the AKP could stay in power only by forming an alliance with the ultra-nationalists in the country. By mid-2010, when Boyacıoğlu and Soyk started producing the web documentary, the former cultural elite, the urban Kemalists, supported by the pre-AKP Turkish state, had lost tremendous cultural prowess, and Zeki Müren, having died in 1996, became a nostalgic figure for a time lost.

The neoliberal conservative AK Party’s victory in 2002 ushered in a considerable cultural change in the country. In the beginning, the AK Party (AKP) introduced legislation to advance freedom of expression as a part of Turkey’s EU bid and its agenda of crippling the military’s power over political institutions. Hence, the first years of AKP rule witnessed an extraordinary shift in the cultural sphere: voices from the periphery, such as Kurds or the religiously conservative, found more opportunities in the mainstream media and cultural discourse. The republican cultural elite, which was the urban elite as the product of Kemalist cultural policies of the Turkish state, was sidelined. The 2010 referendum bestowed upon the AKP control of the judiciary branch; it also gave the party the political tools to silence first the republican elite, and later Kurds since the AKP could stay in power only by forming an alliance with the ultra-nationalists in the country. By mid-2010, when Boyacıoğlu and Soyk started producing the web documentary, the former cultural elite, the urban Kemalists, supported by the pre-AKP Turkish state, had lost tremendous cultural prowess, and Zeki Müren, having died in 1996, became a nostalgic figure for a time lost.

By collecting voice messages from people who “dearly miss” Zeki Müren, the web documentary captures the urban elite’s nostalgia for the pre-AKP era within a cultural landscape they can no longer recognize. In this context, messages emphasizing Müren’s utmost respect for his listeners or his command of “proper Turkish,” a way of speaking Turkish according to the state’s linguistic hegemony which oppressed rural or non-Muslim speakers of the language, are not only about remembering an artist who passed away almost 20 years. Those messages are also expressions of the urban elite lamenting the change Turkey has gone through under the AKP rule. Zeki Müren is remembered not only as an artist whom the Turkish people lost, he is remembered as an undeniable figure of the arts — almost an entire cultural institution on his own that no longer exists.

The web documentary also shatters a misconception about Müren’s fame. Zeki Müren was Turkey’s “Sun of Arts,” but some people chose to remain in the shade. As a young woman recounts how her admiration for Zeki Müren started in her family, she is interrupted by an angry voice. Her father denies listening to Zeki Müren or encouraging such admiration for him in the family. He does not state why he “would have nothing to do with Zeki Müren,” but from his assertion and tone of voice, it is not difficult to guess the denial is tied to Zeki Müren’s gender-bending looks and mannerisms. By showing the audiences such a human interaction where voice carries the deeper meaning of the words uttered, Zeki Müren Hotline exposes the cracks within the myth of nationwide acceptance of a man wearing skirt and make up on stage in a predominantly Muslim country.

The messages left for the hotline are otherwise very positive ones. In fact, they show, at a personal and communal level, how queer people remember Zeki Müren and are now turning him into a symbol of resistance against the patriarchal and heteronormative expectations of society. One of his admirers mentions a sign that read “I asked Zeki Müren, he told me to resist” in the Istanbul Pride Parade, an event that has been banned by the government since 2016. Zeki Müren did not publicly criticize the state; one of his monikers “Pasha” is a term of military authority; and he even left half of his estate to Mehmetçik Vakfı, an association for veterans. But as the web documentary also shows, his life is now remembered as a way of resistance and an inspiring story for the LGBTI+ people in the country. Through these contradictions, Zeki Müren Hotline summarizes the contending legacies of the artist.

Overall, Zeki Müren Hotline is as comprehensive as it can be towards an artist who survived three coups d’état and countless governments while maintaining nationwide popularity as well as posthumous admiration. Besides its success in bringing multiple components of his artistry and reception by the people, the web documentary succeeds in balancing voice, image, word, and digital technology in telling a story while making sure each medium’s strengths are used for the sake of the story.

You might be just starting to learn about Zeki Müren or you might be an avid follower of many memorializations of his life and legacy, but you will still learn so much through the effective documentary making and storytelling methods utilized in the web documentary. Zeki Müren Hotline can be visited here, and it will remain online at least until December 6, 2024.