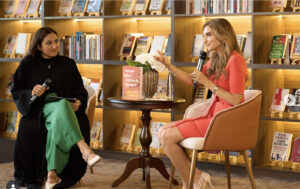

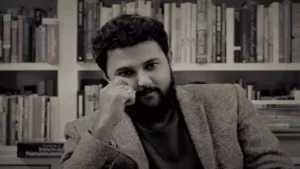

An excerpt from Ayşegül Savaş’s new novel, The Anthropologists, published in July by Bloomsbury.

Ayşegül Savaş

Beginnings and Endings

In a moment of panic, we decided to look for a home. We’d been in the city for several years by then, and from time to time we worried that we weren’t living by the correct set of rules, that we should be making our lives sturdy. I worried more than Manu did, but he often acquiesced to my apprehensions.

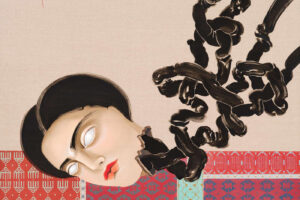

Cosmology

For many years, it had been just the two of us. When we met, the world expanded and it also contracted: it stretched large enough for the two of us—a whole universe—and it left everything else behind a curtain.

We were so young then, barely out of childhood. On weekends, we’d walk off the university campus to spend the day in town, among older people whose lives seemed at once real and unreal. Real, because that was how we imagined actual life in the abstract; unreal, because it did not seem we would ever be like them.

We went to the town bookshop, to the coffee shop, to the record store, even if neither of us knew anything about the type of music sold there: cool and stylish and, to us, exotic.

We were scholarship students in a foreign country, which is to say that we recognized something in each other. We’d been raised by similar types of people— their worries, their discipline, their affection, their means—even though we had grown up on opposite ends of the world. We accepted, children that we were, that we would remain foreigners for the rest of our lives, wherever we lived, and we were delighted by the pros- pect. Back then, it didn’t seem to us that we’d ever need anyone else, in our small world that was also a universe.

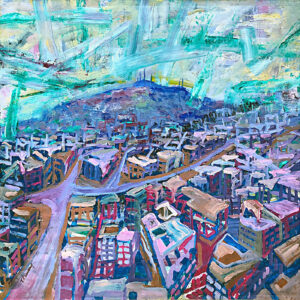

Rough Drafts

We’d arrived in the city on a whim. We had lived in small towns after university, and the city seemed alluring; the start of something else. We had an idea that we would live in other places afterward. For a while, we wouldn’t worry about making things sturdy.

We found an apartment for rent on an unremarkable street, in an unremarkable part of town, and we decided on it without much thought. Back then, we were only playing out our adulthoods rather than committing to them.

Our apartment was small and a little dark, the kitchen not much more than a sink and stove. But we loved it all the same, and for a reason we didn’t clearly articulate, we stayed in the city. Instead of the framed posters we’d had since university, we hung paintings we’d bought at the flea market: a plate of fruits, a port scene at sunset. We liked the paintings, yes, but we also liked what they might mean about us—people with real paintings on their walls. We had a routine; we grew fond of it. Perhaps we were tired of that first rush of excitement in a new setting, and the gradual draining away of color.

Now it was time to expand. To make a life, as some people called it. We wouldn’t have called it that, but we agreed that we had to make things a bit more solid.

Daily Life

Manu left home early to go to work at the nonprofit organization on the other side of the city. While he made breakfast, I made a pot of coffee and sat with him at the table in pajamas. It was a ritual of sorts, sitting across from each other, face-to-face. There were few rituals to our lives, certainly none that carried any history, at least not the history of traditions, of nations and faiths. So these small things mattered. I would make sure to sit with him at the table.

Before he left, we kissed in the hallway. Okay, Manu said, back in my shoes.

Afterward, I lay on the couch and read. I made tea once the coffee pot was empty.

I had just received a grant to make a documentary, though the funding was flexible enough that I could use it for many other things. We wouldn’t need to worry about paying rent for the coming year. The money we saved would help toward a down payment for a small apartment. We had a little more, a wedding present from our parents, though their earnings were modest and the currencies of our native countries were constantly losing value. Still, they considered it their duty; and they were sad, they said, that they couldn’t afford to give us more.

Whenever I introduced myself as a documentary maker, people assumed that I was a sort of journalist, that I was drawn to investigation. This hadn’t been my impulse when I started filming years ago, when I recorded my parents and grandparents, walks around our neighborhood, late-night conversations. Back then it was just an itch, something I did without thinking very hard about. I didn’t worry about the outcome, what to do with the hours of footage I accumulated, about giving shape to anything. I put together bits and pieces to show Manu, stitching together scenes in our particular humor, our shared logic. There was a film about my mother, or rather, about my mother’s wardrobe. Another about the grocer in the neighborhood where I’d grown up, from the vantage point of the owner’s father, who sat all day at the shop. Now that these seemed to me like the work of another person, I could say that they were good films: joyful and naïve. For later projects I traveled to countries I knew little about. I filmed a school for refugee children; a group of migrant women running a soup kitchen from a bus. Sometimes, I believed that making a documentary was a process of empathy, an education. Other times, I thought bitterly that this was simply what documentarians wanted to believe, leaving their subjects as soon as they accumulated the necessary footage. Still, these films taken together gave a sense of social critique, and it was for this reason that I had received the grant, allowing me freedom for the first time in my career.

For now, I knew little beyond the fact that I wanted to film daily life, and to praise its unremarkable grace. I didn’t want to travel anywhere, to investigate the ways of other places, but to remain in the city, and establish some rules.

Future Selves

During our first weeks of searching, we viewed an apart- ment that was even smaller than ours but impeccably restored, with an open kitchen fitted tastefully and resourcefully, and a bathroom that gave the feeling of being in a luxurious setting.

Each time we visited a place for sale, we were intrigued by all the different lives happening in the city, the arrangement of space to work and rest, to store and display; the priorities of strangers that were so different from our own.

The owner was a flamboyant man in his fifties, whose exquisite belongings seemed to have been bought to fit the shelves of his home. After showing us in, he took his place on a leather armchair and let us walk through the apartment ourselves, aware that it needed no explanation. Afterward, we sat at the café down the street, with a red lacquered façade and marble tables. If we were to live there, we said, we’d come to this café for lunch and late-night drinks, and would know the waiters by name. The thought was pleasing though somewhat foreign, as if we’d put on very expensive clothing that didn’t belong to us.

A few days after seeing the apartment, we met up with our friend Ravi at a bar in our neighborhood. We met there whenever we thought we’d have a quick drink, and almost always ended up ordering the platter of fried onions and sweet potatoes and mozzarella sticks, which made us feel sick a few hours later.

We sat at the bar drinking pints of lager and showed Ravi pictures of the apartment from the real estate website. In the photographs, the apartment looked even more like a museum.

Ravi took the phone from Manu. He zoomed in on the round window above a reading nook.

Damn, he said. The Royal Navy.

He then said that it seemed ideal for a couple who received no guests and had no children. That part, he added, was something for us to decide.

So you like it? I asked.

Sure, he said, it’s great. I mean, it is what it is.

Ravi was always throwing things out there, not quite committing to them, not quite letting us know what he really thought.

Principles of Kinship

We’d met Ravi our first year in the city. We recognized in him something we recognized in each other: the mix of openness and suspicion; a desire to establish rules by which to live, and only a vague idea about what those rules should be.

For a while, Ravi was our only friend in the city, and that suited us well. We would meet up every few days and spend hours doing very little. Sit by the river eating peanuts. Walk the whole city, picking out apartments we’d like to live in. Hang out on a square with a bottle of wine. Ravi and Manu liked coming up with setups for comedy skits. Ravi and I liked to discuss traits that made a person alluring and how to do work that inter- ested us. It wasn’t so easy, we said, to know your true passions. Many things seemed appealing on the surface but after a while, they felt oppressive.

For a living, Ravi tutored high school students and also managed online advertisements for a retailer on the other side of the world. It had taken us months to find out how he made money, because he always skirted the topic, perhaps embarrassed that he wasn’t doing work he truly loved. It was often the case, for people our age, that an interesting job was tantamount to being an interesting person.

Whenever we went over to Ravi’s studio, Manu and I would look through his collection of photographs, posters, old manuals, journals, and textbooks. He found them at flea markets and on the street, always with an idea of ways he would put them to use, though he never did. His true passion was collection, the accumulation of expired things, their foggy poetry.

This stuff is so cool, we always told him. You should really do something with it.

Yeah, Ravi said, I will.

This was the other thing: it seemed that our interests could be legitimized only if we made something of them—a book, an exhibit. We often said what a shame this was; we romanticized artists of past decades, doing work with great joy and creativity without turning it into a product.

Still, we belonged to our own times.

The Markaz Review thanks Bloomsbury for permission to share this excerpt.