Kurdish poetry abounds but rarely appears in English. This new translation presented in a bilingual English-Kurdish edition is forthcoming from Pinsapo Press in September.

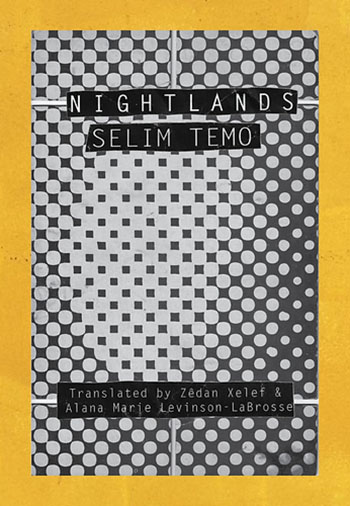

Nightlands, poems by Selim Temo

Translated from the Kurdish by Zêdan Xelef & Alana Marie Levinson-LaBrosse

Pinsapo Press 2024

Jordan Elgrably

Many peoples have been conquered and crushed, but perhaps none more in the center of the world than the Kurds, who despite having a culture, a language and a history all their own, find themselves beleaguered and betrayed in the nations where they reside: Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. To appeal to the populace, despotic leaders denigrate and deny the cultural sovereignty of their country’s minorities: predictably, Stalin repressed Yiddish culture in the USSR, while in Spain, Franco excluded the Basque and Catalan languages from the education system. In the United States, there were an estimated 245 indigenous languages, yet it wasn’t until 1972 that Congress passed the Indian Education Act, which made it legal to teach native languages in public schools. In Turkey, where Kurds have been targeted by the government for decades, it wasn’t until 2012 that PM Tayyep Erdogan announced that Kurdish could be taught in state schools.

Yet despite what appeared to be a thaw in Turkish-Kurdish relations, as Karwan Faidhi Dri subsequently noted in Rudaw, “Kurds make up around a fifth of Turkey’s population, but few are able to speak their mother tongue. Turkish is the country’s only constitutionally recognized language. It is the language of employment, education, any public institution. By contrast, the Kurdish language has suffered from waves of criminalization in Turkey, with restrictions on its use relaxed for political leverage.”

It is in this context that one comes to contemporary Kurdish literature, little of it available in English until recently. The small New York press Pinsapo, however, has recently launched its Kurdish Poetry Series, with a first book out in September by exiled Kurdish poet Selim Temo. Translated by Zêdan Xelef and Alana Marie Levinson-LaBrosse (who has previous experience translating Kurdish writing, including work from Kajal Ahmed and Farhad Pirbal), Nightlands is a bilingual collection of poems from Temo, who lives and teaches in Paris. In publisher Öykü Tekten’s series introduction, she notes that Kurdish isn’t a monolith, and that the intention is to translate work from Gorani, Kurmanji, Sorani and Zaza — “four of the major Kurdish dialects. We include poets from Kurdistan … as well as from Khorasan, Palestine, Lebanon, Israel and other regions with diasporic Kurdish communities.”

Picking up Nightlands, one is struck by the opening poem, “Vae Victis I: Reproach,” which is preceded by the well-known story of the barbarian capture of Rome, when the Roman commander is told “vae victis” or “woe to the conquered.” Temo writes:

do not ask me

what is vanquish?

history is yesterday’s child

While many Kurdish writers live exiled from their native lands, many more choose to stay and combat government repression. Kurdish newspapers, printing presses, and cultural centers exist, or subsist, even as many academics face widespread discrimination and the teaching of Kurdish culture and history meets with checkered success.

In Temo’s “Now, Somewhere,” the poet evokes his existential struggle:

[…] the voice does not return from the gorge

no echo reaches the blind sky

I am a hunchbacked mountain collapsing in a distant plane

I rot in a book with no pages, no letters

where I have fallen, no hand reaches for mine

Further along, the poem avows that exile is a curse:

[…] pain speaks this language

loss and grief splatter from each word

here in exile it tightens around my neck

Inevitably while reading Selim Temo, I was reminded of exiled and murdered Palestinian poets and writers, and put in mind of the incalculable loss of all those poets around the world over the past century who have been censored, jailed or who suffered death at the hands of the state (and the list is long). This does not include those who have simply remained marginal in history’s pages. What a tragedy it is for world literature that little treasures such as these are so hard to find, so few and far between. Reading the poems in Nightlands in English, side by side with their Kurmanji original versions, I found myself both delighted and determined to uncover more literary voices that are further afield from our usual bailiwick.

With respect to Kurdish writing, I could begin by consulting a list of 20th and 21st century Kurdish poets and writers available on Wikipedia, and certainly there is last year’s Kurdistan +100, published by Comma Press in its “Future Past” series. I could also consult the Kurdish Academy and World Literature today for poetry. However, the number of Kurdish literary works available in English still remains disappointingly limited. That is why one wants to applaud and support Pinsapo’s Kurdish Poetry Series, and treasure Nightlands as one of the few recent volumes of Kurmanji poetry available in translation.