Art exhibitions and new books push back against a year of cancelling Palestinian art, culture, and voices.

Malu Halasa

After a year of the war on Gaza, signs and symbols, art, and visuals from and about Palestine are still being banned, dismissed or ignored. In the US, pro-Palestinian slogans and signs have been removed from college campuses, and professors have been “advised” by university administrations not to express their views. Like American universities, museums and cultural institutions, once bastions of free speech and dissent, have been running scared. In September Pulitzer Prize winning author Jhumpa Lahiri declined an award from the Noguchi Museum after three of its employees were fired for wearing keffiyehs. Pro-Palestinian posters were responsible for one employee losing her job and others resigning from the 92nd Street Y. Even a pin of the Palestinian flag caused ruptures — although Y bosses allegedly told the employee wearing it that a pin showing an Israel flag would be allowed.

In London’s major museums, censorship has taken on a more subtle form of indifference or outright avoidance. The extravagant Silk Roads exhibition in the British Museum ignores Gaza, an important entrepôt between the eastern and western Mediterranean the historic trade route in spices, incense and fabrics. As Katherine Pangonis has observed in her essay “Written in Fabric” from the new anthology Daybreak in Gaza: “… gazzatum — a finely woven fabric of linen or silk threads, called gaze in French and gauze in English — was derived from the place name of Gaza, from where it was thought to have originated.”

The Victoria & Albert Museum organized an important summit during the 2022 Women Life Freedom protests in Iran and included graffiti stencils of the faces of dead Syrian protestors after that country’s failed Arab Spring. The museum’s blind spot when it comes to Palestine has been glaring. One wonders if it will also ignore the events in Lebanon. Apparently some resistance movements are sexier and more acceptable than others.

Art and words are intermeshed in the cultural frontline that has become Gaza’s tragedy and humanitarian crisis. This spring at London’s Barbican Centre, two collectors withdrew their works from the exhibition Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textile in Art after the Barbican cancelled the talk, “The Shoah after Gaza,” by Indian novelist and socialist Pankaj Mishra. However, in September, the Barbican corralled its institutional nervousness and hosted “Voices of Resistance,” a panel of writers and activists organized by Comma Press. The panel had been scheduled to take place at the HOME Manchester theatre and gallery space in April. The venue cancelled the event after the Jewish Representative Council of Greater Manchester and Region circulated false allegations of antisemitism and Holocaust denial against one of the panel’s participating writers, Atef Abu Saif, the author of Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide. It was just one of many instances of censorship over the past twelve months that the Iraqi playwright Hassan Abdulrazzak wrote about for The Markaz Review. Interestingly after a public outcry HOME reinstated the panel, which went on to the Edinburgh Book Fair. For venues and festivals there is safety in numbers.

Empty Chair

When the institutions opt out or prevaricate, smaller, potent initiatives fill the void. The current exhibition at P21 Gallery, Art of Palestine|from the river to the sea, on until December 21, features the paintings, drawings, and installations of 28 artists. The exhibition was brought to London by Palestine Museum in the US, and includes tapestry and Gazan children’s drawings from the 2008 Israel’s Operation Cast Lead military campaign against Gaza.

Art of Palestine opens with a brightly colored and textured, acrylic painting of a tranquil landscape, by one of the founders of contemporary Palestinian art, Nabil Anani. The large-scale painting shows rows of trees, placid farmland, and the rolling hills where Raja Shehadeh once roamed in Palestinian Walks before the Palestinian countryside was divided by a separation wall, settler-only highways, and vandalized olive trees. The painting’s title, “In Pursuit of Utopia #7,” speaks volumes as the onslaught on Gaza continues, and settler violence on the West Bank and Israel’s ground incursion into Lebanon intensifies. Anani says he has always “been passionate about … the beauty of rural life and the breathtaking landscapes of Palestine.” His solo exhibition The Land and I, is on until January 12, 2025, at Zawyeh Gallery, Dubai.

Artists from Gaza, in London

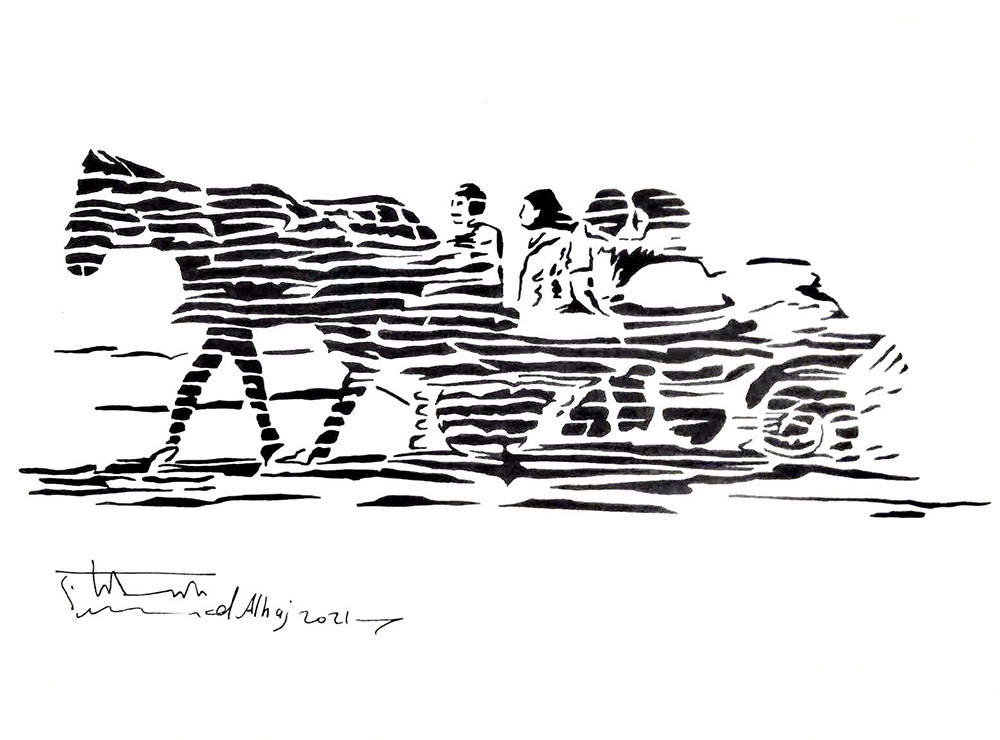

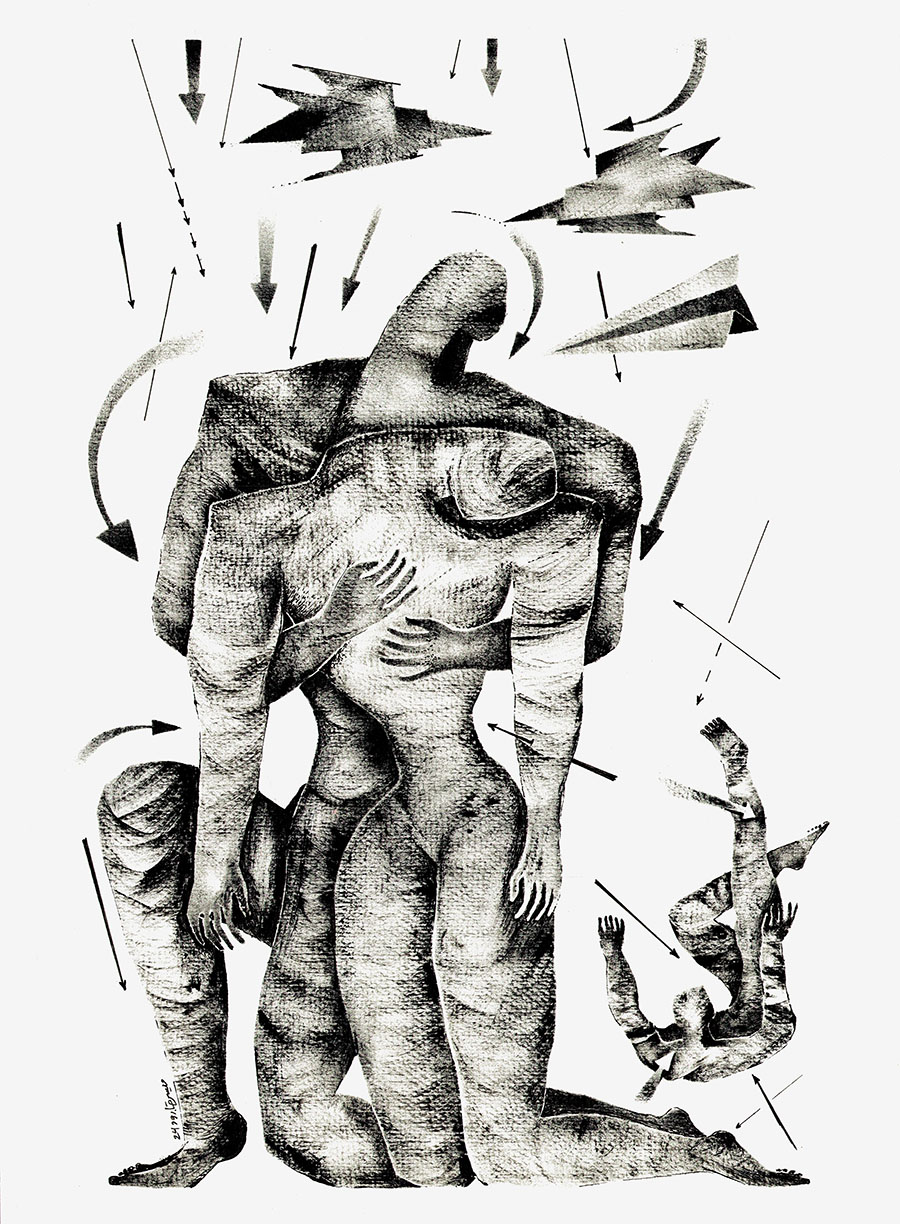

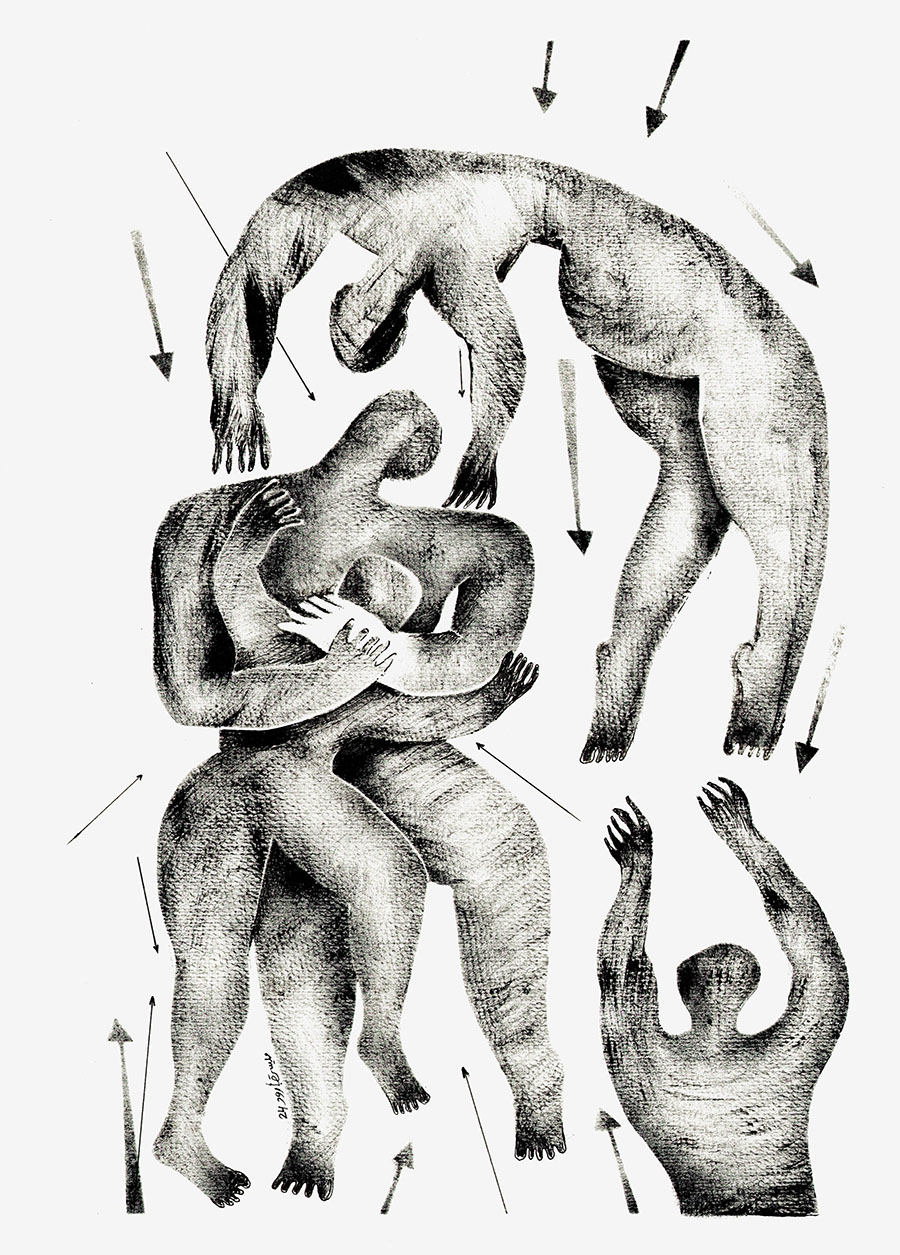

In Art of Palestine at P21, Gazan artists Mohammed Alhaj and Maisara Baroud both rely on materials relatively easy to keep hold of during displacement and bombing — paper, pencils, and black ink pens. Baroud has been drawing a daily diary of the war to show, as he has written in the Guardian, “stories of destruction, loss, death, weakness, displacement, fear, pain, patience, resilience and breaking.” The human figures in his drawings are angular, filled with emotion. He continues, “The story is of a war that has a massive ability to harm and that defeats distance and geography at the speed of sound, bringing death to more people in less time …”

Both the College of Fine Arts at Al-Aqsa University, where Baroud worked as a lecturer, and the house he lived in with his ten children, have been razed to the ground. For him, “Drawing … is also the only way to announce: ‘I am still alive.’”

Fellow Gaza artist Mohammed Alhaj’s artwork in the exhibition includes his fragmented black ink series of drawings, and an acrylic painting. In “Immigration” (2021), the view of figures in shadows is seen from a distance. They mill about in a dystopian landscape of dark yellows and browns, alone or isolated even within a group, to suggest they are on the move but getting nowhere. It is a scene with variations the artist often revisits in his other similarly hued paintings.

Artworks by Alhaj and Baroud have also been included in the Palestine Museum’s Foreigners in their Homeland exhibition at the European Cultural Center’s Palazzo Mora in Venice, which coincides with the city’s biennial until November 24. Faisal Saleh, the founder of the Palestine Museum, was in London for the launch of Art of Palestine. He gestures at Baroud’s 16 drawings hanging from the P21’s ceiling, and AlHaj’s three displayed vertically on a nearby wall. The only reason these drawings made it to London and Venice is that they came to Saleh as digital files. AlHaj’s painting was one Saleh acquired for the Palestine Museum before the 2023 war.

“Now,” he says, “it’s impossible to get artwork out of Gaza.”

The titles of some of Baroud’s drawings provide intimate glimpses of the artist’s day-to-day existence. One, for example, is called “Coincidence … (is that you are still free)”; another is “Oh, my killer slow down a little”; and then there is “My beautiful cat (Sarah) gave my children her seven lives before her flesh was chewed by the steel bird.”

After the October 7th Hamas attack on southern Israel and Israel’s unprecedented onslaught against Gaza began, the Palestine Museum organized a program of artworks by 35 artists from inside the occupied territory. Saleh offered the art to exhibit for free to museums around the world. With the air of a man fighting an uphill battle, he shrugs, “Not a single one of those museums responded. There is real interest from the public but the institutions are afraid to touch anything that says ‘Palestine’ on it.”

One of the showpieces in the Art of Palestine exhibition is “Venetian Red,” (2021), a painting of red, orange and yellow licks of flame, by Palestine’s leading abstract artist Samia Halaby. Her first major retrospective in the US had been scheduled at the beginning of this year at Indiana University at Bloomington’s Eskenazi Museum of Art (EMA). It was suddenly cancelled due to “security” concerns, or so said museum officials. Eventually the exhibition, which opened in Michigan State University Broad Art Museum and remains on display until December 15, suggests few terrorists in America’s Midwest target abstract artworks.

Why are Palestinian art exhibitions cancelled and museum workers displaying signs of pro-Palestinian views fired?

Faisal Saleh doesn’t hesitate in his answer, “Because the people who donate to all these institutions are Zionists, and they will retaliate against the museums. It is the same thing with the universities. The reason the universities are calling the police to beat up the students is because their big donors are Israel supporters. This is where we are after a year of the war on Gaza.”

Decolonizing Art

There have long been tensions between aesthetics, activism and politics in art from places of war, conflict and occupation. Some work in Art of Palestine is map-based. In P21, the large floor map by the historian and cartographer Dr. Salman Abu Sitta, founder of the Palestine Land Society, shows “Historic Palestine” before 1948 marked with the names of its original cities, towns, and villages. The fate of some of those places is revealed downstairs a two-screen video installation “Nakba Animated Map,” 2023, by architect, urban planner and virtual reality artist based in Tokyo, Nisreen Zahda. The grim power of the video installation is how fast and brutal Israel’s ethnic cleansing was during its so-called “War of Independence.” Zahda assigned “one second for every depopulated and destroyed city, town or villages by Zionist troops” during the Nakba.

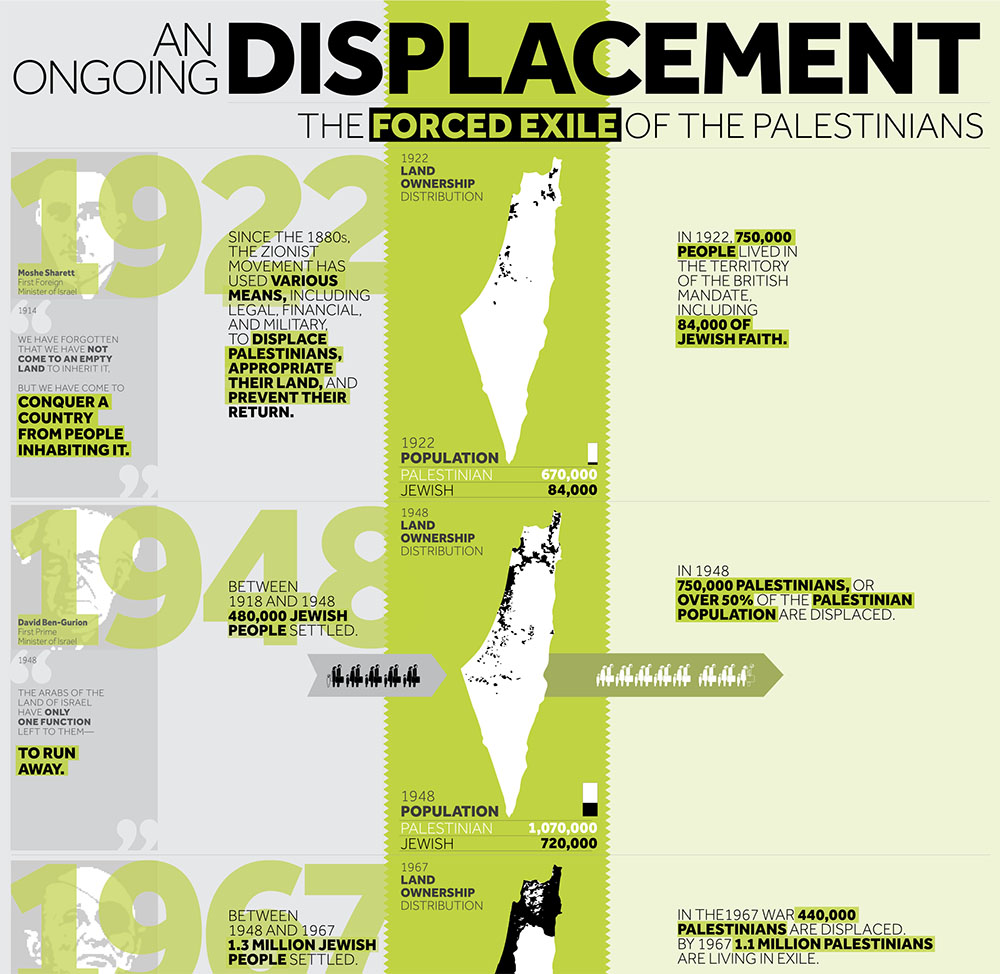

Dr. Salman Abu Sitta is cited in the new book Visualizing Palestine: A Chronicle of Colonization and the Struggle for Liberation, edited by members of the Visualizing Palestine collective, Aline Batarseh, Jessica Anderson, and Yosra El Gazzar, as being an influence on VP’s series “Return Is Possible.” The poster draws attention to the fact that the “vast majority of destroyed Palestinian towns and villages” by the Israelis “in historic Palestine have not been built over.” These would be available for resettlement by Palestinian refugees, as stated in UN Resolution 194. Although the Palestinian right of return has been prevented by Israeli authorities, who instead invite Jews from all over the world to immigrate to the country and become immediate citizens of Israel. Perhaps because of the news, people have started to contact the curator and director of P21 Yahyah Zaloom, with an interest in purchasing Palestinian art. For him, this is bittersweet. He says, “Every artwork sold means an artwork the public will not see.”

P21 has always been less a commercial gallery and more a platform for Arab art. In 2013, he encouraged a group of artists and activists to organize #withoutwords: emerging Syrian artists, one of the first exhibitions in London of new art from Syria, after the country’s failed Arab spring, which I helped to curate.

Since October last year, P21 has put on a nearly continuous program of Palestinian art and events. It has hosted Az Theatre’s multiple stage readings of Hossam Madhoun’s “Messages from Gaza Now” that were excerpted in The Markaz Review. At a time when funding for the arts is low in Britain, Zaloom is clear: “From my point of view if I empower the stakeholders, the artists, the curators, even our board members, I can give them more support in doing projects. It is much better than me doing events and exhibitions as a Palestinian.”

In a report to the UK’s Museum Association, he describes the majority of P21’s exhibitions and events as dealing “with issues related to decolonization …” and that is “a critical endeavor that involves unraveling entrenched colonial narratives, acknowledging historical injustices, … valuing diverse cultural perspectives … [with] a commitment to rectifying past wrongs.”

In being closely involved in both the arts and Palestine, he does believe that since October 2023 “outside forces have been trying to stifle Palestinian voices,” and agrees that programming Palestinian art exhibitions and events has been more difficult for public-facing institutions as opposed to publishing houses which produce books on Gaza and Palestine without fail. These companies don’t seem to encounter the same level of open hostility and criticism from pro-Israeli groups.

The Art of Infographics and the Infographics of Art

Hand in hand with the protests that have rocked mostly US art institutions and universities has been the need for more information. Filled with infographics posters and education kits, the book Visualizing Palestine takes as one of its many starting points this quote by Hisham Mattar:

The Arabic muthahara, the Persian tathaharat, the French manifestation, the Italian manifestazione and the Spanish manifestación –– all, regardless of their variant linguistic roots, agree that in a demonstration there are at least these two sides: one concerned with making something apparent and the other with objection … [O]ne could argue that in order to protest one needs to make something clear.

His words seem particularly relevant to the continuous state of cancelling Palestinian art and visuals by anti-Palestinian forces.

The clear, brief, simple to read, even easier to understand infographics posters by the collective Visualizing Palestine cover the major issues affecting Palestine as seen by the chapters in their book, from “Settler Colonialism,” “The Ongoing Nakba,” and Ecology to US and “Corporate Complicity,” among others. The chapter “Navigating Apartheid” outlines some of the daily travails Palestinian people face: the segregated road systems, the segregated bus routes in greater Israel; the comparison between the banning of African Americans in the 1960s from public transport with the banning from transport that Palestinians face today; forced birth by Palestinian women at Israeli checkpoints; and the control in the occupied territories of mobile phone coverage, alongside water, electricity, currency, the legal system, population registry, import and export of goods, and of course land, all by a bigoted Israeli state.

The editors of Visualizing Palestine point out that these are examples of what Edward Said referred to as “reading Zionism from below,” i.e. “from the standpoint of its victims.”

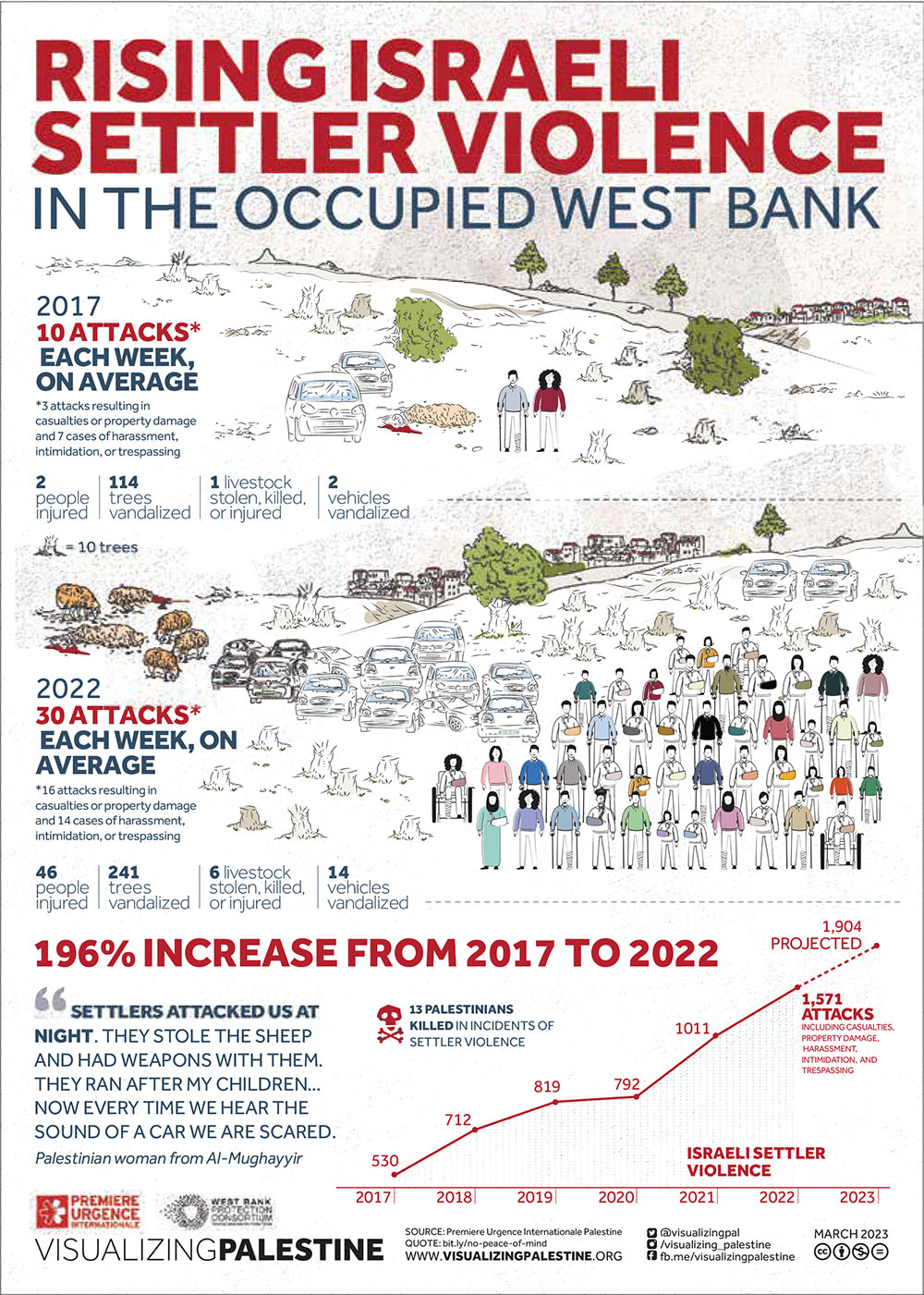

Old and new maps are included in their book. “Palestine Shrinking, Expanding Israel,” covers the years from 1918 to 2017. Taking in the proliferation of illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank today, the turquoise colored area of Palestine would be even more encroached by Israel represented by the color black. With the acquisition of land comes violence and the poster “Rising Israeli Settler Violence on the Occupied West Bank” reveals a 196% increase from 2017 and lists the numbers of people injured, trees vandalized, livestock stolen, killed or injured, and vehicles destroyed. Statistics from 2024 would only be higher.

VP’s infographics are a radical reminder that genocide is an integral component of settler colonialism. Somehow made even starker in VP’s bold graphic design are the documented, racist statements made by Israeli officials cited in the poster, “Intent to Dominate” (that includes quotes from Netanyahu from 2020 to Ariel Sharon, from 2000). Still other posters, which directly quote official statements by Israeli politicians, pull back the curtain and reveal the real thinking behind Israel’s assault on Gaza.

Starvation as Israeli State Policy

Even the roots of Israel’s concerted effort to limit food to the Palestinians in Gaza are clearly documented in a series of VS infographics, from 2018. Three posters, titled “According to Israel, Palestinians need 43% less dairy than Israelis;” “According to Israel, Palestinians need 19% less meat than Israelis;” and “According to Israel, Palestinians need 37% fewer fruit and veggies than Israelis,” all include the chilling line: “40% of Gaza’s households suffer from severe food insecurity largely as a result of Israel’s blockades.” The slide from limiting food to aiding and abetting starvation comes full circle by October 2023, as attested to by the VP poster “Besieged.” It states, “Gazans received 2% of the usual amount of food.” Surely the percentage is far less for those still in Gaza. According to news reports, people have started eating the mulberry leaves and wild khubeezeh or cheeseplant to stave off starvation.

It is times like these that activism is forged. The annex in Visualizing Palestine dissects the conceptual thinking and visuals behind the collective’s infographics. By being transparent and showing their process VP hopes to inspire others. The inception of each of their posters starts with a research brief that instigates the process to “clarify the messaging, goals, and framing of a visual.” Complex data research, images, and information is filtered through VP’s template, called the “process wheel,” which encourages rigorous message making. Then partners, experts, researchers and designers criticize, comment on, and amend a poster before it is published on the VS website. All their posters are free to use under a Creative Commons license. The collective’s aim has always been to create visual stories for social justice. They utilize “data and research to visually communicate Palestinian experience to provoke narrative change.”

After a year of an ongoing war and with — at the time of writing — a conflict turning into all outright war in Lebanon and beyond, information in books like Visualizing Palestine have never been sharper or more forthright. Myriad, authentic experience can be felt, seen, and heard in exhibitions such as Art of Palestine. Yet ordinary people, who object to genocide in Gaza — whether they’re artists or writers — are being silenced and in some cases fired. How to break through the walls of propaganda, censorship, and fear is the question that remains.

A literate, fascinating, important, “artsy”-yet-intensely-political contribution by Ms. Halasa…Kudos!

(I was especially pleased to peruse the coverage of Dr. Salman Abu Sitta … about 20 years ago, I co-produced pro-Palestinian fare on my local-area public-access cable TV system in which we featured Dr. Abu Sitta’s pointed analyses and positions regarding “land/geographics” in the ‘holy’ land.)