The words that form a map of queer language in the Middle East.

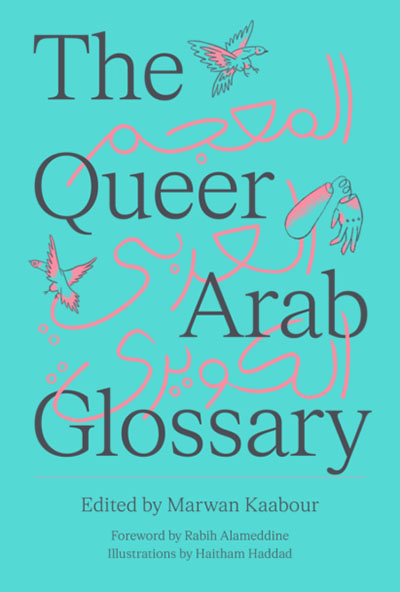

The Queer Arab Glossary by Marwan Kaabour

Saqi Books, 2024

ISBN: 9780863560927

Bahi Ghubril

Are you a child of Mickey (-mouse) or merely a flamboyant chandelier?

If you’ve ever been approached, and somewhat bemused by such a question at a cool gathering in Khartoum or in the Zamalek district of Cairo — where “a child of Mickey” is an euphemism for a gay boy in Sudanese dialect and “a chandelier” describes an effeminate man in Egypt — then you certainly need a copy of The Queer Arab Glossary. It will help you decipher meaning and and motive. Or so the theory goes.

Edited by the young and valiant Marwan Kaabour, a Lebanese graphic designer now living in London, The Queer Arab Glossary is part academic research, part social commentary. At its core, it is as much a glossary to Arabic slang as an appendix is to a thesis or an essay, attempting to explain, define and unravel some of the esoteric meaning of language used by contemporary queer Arab society. Kaabour expounds in his introduction: “When the language we inherit does not equip us with the tools to speak about ourselves, we create our own Queer slang in a way to identify with other members of our community. It is a form of social recognition and a form of protest.”

In addition to the glossary itself, the publication includes essays from eight contributors on queerness in the Arab world. The forward, by the Lebanese novelist Rabih Alameddine, succinctly explains the raison d’être of the publication, as it covers the strong link between a subculture and language.

“One of the first things any group does when forming an identity,” he writes, “is play with language. Whether the group consists of members of a police department, of university students, residents of a city, British expats in Cairo, or African Americans in the US South, they will change dialects, invent new words, introduce new meanings to them. Sometimes the change is to simplify communication. Sometimes it’s to stop others from understanding what you’re saying. For the most part, however, groups create a new language to consolidate identities by increasing what the members of said group have in common and, just as important, by excluding others who do not belong. These Shibboleths are the glue that bind. They make members feel at home within that identity.”

Methodology

In his introduction, Kaabour presents us with a candid account of his journey, both physical and metaphorical, from Beirut to London, and from the world of design to that of research and sociology. His engaging description of the trials and tribulations of sourcing, analyzing, archiving, and presenting the list of word entries that encompass The Glossary is a fascinating revelation of the methods, challenges and obstacles in creating such a publication, technically as well as logistically.

Kaabour embarked on a two-year long process of having one-to-one discussions with queer people from across the Arabic-speaking region. He endeavored to connect with people from different countries, as well as different parts of the same country, in various and varied communities. He asked them about terms with which they were familiar and enquired about their meanings, contexts of usage and to whom these words are normally said. That same exercise would be repeated to ascertain and confirm the results, without shying away from celebrating some descriptions that often have conflicting meanings in different contexts, communities, or time — such is the rapid change of slang.

Without remorse or apology, Kaabour is sincere in his belief that The Glossary is a work-in-progress and has presented it as a snapshot in time. This work is ongoing and he encouragingly invites further development of the subject matter, with a wonderful array of possible paths of what is to follow, from himself, or from anyone else, including readers. Some people will disagree with various entries’ definitions, and the editor welcomes debate as it can help to further enrich and expand the work of The Glossary. No study of a similar nature can ever be conclusive: it can however pave the way for additional research and more advanced analysis.

The Definitions

The actual glossary of around 330 entries, in printed black typeface on turquoise paper, comprises only half of the book. Effectively it is a dictionary that covers the lexicon of the queer Arab community in all its differences and quirks, featuring fascinating facts and anecdotes, with sometimes witty and sometimes crass illustrations accompanying the slang expressions.

At its core, the list of words or compound words is meticulously organized and sorted by Arabic alphabetical order. These awkwardly require a knowledge of the sequential Arabic alphabet to efficiently look up a specific entry. Each one is accompanied by an English transliteration, followed by a short paragraph that defines the word in English and Arabic and gives meaning often by providing information about the word’s origin and contextual usage; for example, the word okhti does mean “sister.” Sometimes pronounced as okhtshi, according to The Glossary: “it is an endearing term used by queer men to refer to their queer ‘sisters’: sometimes the sh is added in the middle of the word for verbal emphasis.”

Many entries are accompanied by illustrations, which elaborate further on the definition. All the entries are used in slang queer language, and most are derived from Arabic words, though a significant number of the entries have roots originating from French, Turkish, Persian, or other languages that have made their way into the local spoken dialect. The Glossary also informs us that the word bofta “is an Arabization of the British slur ‘poofter’ and used” — primarily in Libyan dialect — “for an effeminate man assumed to be gay.”

Like most spoken slang, many words are carved out of the mother language, Arabic in this case, and are words that would be also used in everyday communication, not specifically for, or by queers. As a result, most of the listed words would be found in a traditional dictionary which would provide the word’s intended mainstream meaning. In The Glossary, apart from the conventional meaning, the queer definition of the word is offered, and how it would be used in the context of queer language.

The entries, divided into six sections, each represent a regional dialect or vernacular of the spoken Arabic language, broadly broken into the geographical areas of the Levant (Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, and Jordan); Maghreb (Libya, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunis); Egypt, Sudan, and the Gulf (UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Yemen); and Iraq. This by itself is a courageous feat, and Kaabour touches upon the complexity of dividing the region into vernaculars based on political state lines since many of the dialects and words know no such boundaries.

He observes: “The state and political borders that ensued do not necessarily reflect the cultural homogeneity of the communities that live within these borders. Language and vocabulary do not acknowledge political borders, but rather travel freely and bleed across, visa-free.”

Though commendable and often humorous, this elaborate re-defining of each word’s meaning specifically within queer communications is often predictable and slightly redundant. Most of the words’ queer-intended meanings would be simple to guess in context of when and where (and how) the word is said. For example, ‘Maftūh’, which means “open” or “opened” in the classical sense i.e. the shop door is open; the can was opened, doesn’t necessarily need a published glossary to explain the meaning when said in context of “that guy is wide open.”

In addition, some of the terms used and listed are simply switching the gender pronoun ending of the traditional Arabic noun or adjective. The closest example of this in English would be replacing “he” with “she” if referring to a gay or effeminate man. Useful perhaps for the non-Arabic speaker in understanding the mainstream meaning of the word, but otherwise the intended meaning would be inferred from the context.

Intriguingly, there is a disproportionate number of slur word entries that verge on derogatory slur words — the various ways of saying “gay,” “effeminate,” “enjoys being penetrated,” “paedophile,” etc., usually meaning one type of queer or another, compared to those words that would be displaying affection, passion, or even quirky or mischievous queer acts in a playful way. Kaabour invites the reader “to engross yourself in the glossary’s entries, which run the full range of emotions: harrowing, peculiar, hilarious, shocking, saddening, joyful, sweet, and sinister.”

Complexities of Language

Herein lies the biggest obstacle of The Queer Arab Glossary: how to transmit that gamut of emotions in a concise dictionary. Slang expression exists on several dimensions; for these are words decorated by tone, intonation, facial expression, physical expression, nonverbal sound effects and affected by context and community. The published canon, notwithstanding the effort and creative exertion it must have taken to research, identify and define them, results in a rather dry, rigid, matter of fact rendering of slang words dependent on the use of normative language. What is lost in translation is the spectrum of emotions, and how these words should affect the listener, together with the rich tapestry of nuanced allegations, be it mischievous flirtations, intentional playfulness, or damning allegations.

Given the complexity of the language and nuances of the queer society in transmitting pleasant, flirtatious, whimsical, or derogatory statements, this work falls slightly short of attaining status as a queer glossary. It lacks nuances and subtleties, soul and wit, and often reads as a carved-out selection of words of the full Arabic-English dictionary that relate to nouns or adjectives that describe gender, sex, or sexuality. It is useful perhaps for the non-Arabic speaker, as a quick cheat method into speaking and understanding like a native, but this very narrow range of words is unlikely for those living in, and more familiar with, the region. Thus the work is a list of words that form a map of queer language that could very well be a first step in a continuous, unfurling academic work on culture and language. Unfortunately, due to the lack of contextual wit, or humor, it falls short of being fun, witty and commercial. It is a publication that could potentially drift into the valley in between academia and commerce, belonging fully to neither one but partly to both.

The last section of the book provides a series of harrowing and humorous essays that offer insights and help place the slang expressions and feelings into the context of a modern social and political framework. The essays, contributed by an impressive list of activists from the world of academia, journalism, music, art and design from across the Arab world, address how language and culture shaped them or the communities around them, vis-à-vis queerness. The essays are a powerful response to pervasive myths and stereotypes around sexuality, and an invitation to the reader to take a journey into queerness throughout the Arab world.

The essay “Ancestries” by Lebanese lead singer and songwriter of Mashrou Leila, Hamed Sinno, perhaps best describes the challenges in defining slang language full of innuendo by way of normative words, firmly solidified in print. He begins by explaining how short vowels used in Arabic language, called tashkeel, are traditionally omitted, and Arabic readers and writers instead know how to pronounce different words based on a combination of memory and context. The same sequence of Arabic consonants can have different meaning depending on how said sequence is animated by the speaker. We could pursue this vector to deduce that choice of vocalization also changes meaning, and, by interpolation, the choice of tone and intonation changes the intention. A commonly used word spoken innocently in everyday speech could have very different connotations once uttered, whispered, or shrieked frivolously! Hamed continues to narrate early childhood memories of his elders warning him against song: “It is not words themselves but the ecstasy of song that threatens to lead the person astray. The sin is in the joy.”

How blissful!

What The Glossary lacks in its depth as a final comprehensive dictionary of queer Arabic words offering meaning and context, it more than makes up for in the breadth of the work.

An Essential Archive

Undoubtedly it is a snapshot of contemporary queer Arab culture. The glossary also acts, for Kaabour, like an archive, who writes, “As queer elders pass, a great wealth of knowledge and wisdom passes too. For young queers, it might be a lifelong challenge to navigate the murky and treacherous waters of understanding not only themselves but how they exist within a community and society. Perhaps a project like this book might help pass on the knowledge and facilitate young queer people to have a footing firmly fixed in the ancestral past, a more nuanced understanding of today and the tools to help navigate an uncertain future.”

He concludes, “This book also debunks the myth, adopted by misinformed Westerners with underlying Islamophobic sentiments, that people of this region are inherently homophobic, backwards, and unable to make space for or to embrace queer people. Not only do queers exist in every section and every stratum of this region but we have been talking about [queerness] for centuries now. This is not to undermine the many challenges marginalized communities in our region face, but rather it is a defiant proclamation of wanting to understand these challenges and resolve them with our kin and not via a parachuted savior.”

His book brings under the spotlight a rich tapestry of spoken Arabic queer words in many of its dialects and vernaculars infiltrated by or infiltrating other communities, languages and cultures. It deserves a much wider audience than queer Arabs, as a first step in a continuous study of slang Arabic, an etymology of words, and an ode to queerness within the Arab world.

As Alameddine rightly states, “What you have in your hands is a lexicography of the language of queers across the Arab countries, a book of shibboleths.”

At once a glossary, but not quite a glossary, this is more of a compendium to gender history and development within the context of a wider society and anthropology in the Middle East. The Queer Arab Glossary is an insight into Arabic grammar and etymology, a snapshot of slang Arabic language, and an anthology to the ever-fascinating link between language and identity.