Working in a farargi butcher’s in Kom el-Dika, in Alexandria, a foreign, Arabic-language student makes friends, breaks gender and religious barriers, and learns halal slaughtering.

Bel Parker

Chicken and rabbits were crowded into green cages and blood was spattered red upon the pale worktops. The de-feathering machine thundered in the corner, light danced on slicked knives and glistening flesh. There was a sharp stink. It was the first time that I passed Hatem’s butcher shop and the drama of live slaughter had me transfixed.

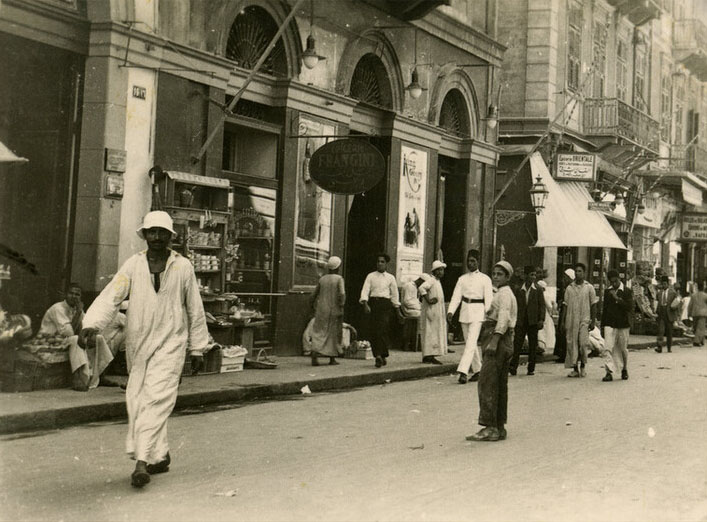

I was an Arabic student on a year abroad in Alexandria, hungry to experience the local language and culture, yearning for a foothold in a new city. When I first walked through the narrow streets of Kom el-Dika, it was as if I had stepped onto a stage: I became a curious attraction in a small world where everyone knows each other’s business.

Written about, sung about, Kom-el Dika is steeped in history. Its name translates as “hill of rubble”; it is built on ancient ruins and the vestiges of its beautiful architecture can still be found among the recent, cheaply built apartment blocks. Most Alexandrians recognize the area as sha’by — which means “of the people,” and suggests tradition, working class, and local craftsmanship.

Camera in hand, I wandered through the quarter until I reached a little square in its center. On one side was a busy café named after the famous musician Said Darwish who took his daily coffee there over 100 years ago. Opposite the café was the butcher’s shop. I saw a chicken plucked squawking from its cage, and I lifted my camera. I heard the name of Allah before a knife sliced through the chicken’s throat and severed its blood vessels. Click. The chicken was thrown into a big black bucket as blood started to pump from its neck and, while it blinked and spasmed, another chicken was chosen. Click. The second animal was thrown on top of the carcass of the first. Click. In Kom el-Dika, a chicken that arrived alive from the farm in the early morning could be slaughtered, carved up, and served for lunch later that day.

I was fascinated by the immediacy and matter of fact-ness of the slaughter. I just could not imagine anything like it in a UK city. It felt so distant from our pre-packaged supermarket drumsticks, so at odds with our squeamishness and our general aversion to death, that I had to step into the shop to meet the butcher himself.

If I surprised him with my Arabic, stilted as it was, I was equally surprised by his effortless English and strong Irish accent. Hatem was born in Jordan, raised in Kom el-Dika, and had worked in construction in Ireland for 15 years. That first day, I sat on one of the chairs by the entrance, drinking cup after cup of sweet tea, watching him skillfully skin rabbits and chat animatedly with friends, family, and customers who drifted in and out. Hatem’s shop was a farargi, I came to learn — a butcher that specialized in poultry and rabbits.

There was an easy intimacy to the interactions at Hatem’s and I instinctively wanted to share in them. Maybe this was a place that I could be part of, not just on the outside looking in. I asked Hatem if I could work there. A short period of wooing took place between us. I was given the job of cleaning out the chickens’ stomachs and worked hard to prove myself. He, meanwhile, plied me with food, tea, and coffee, and in the quiet moments we would sit together and gossip about the customers passing through. By the end of the second week, he bought me my own pair of wellington boots so that I could safely charter the flooded and bloodied shop floor. That was our version of a contract.

An Unusual Apprenticeship

I began to sense a rhythm in the working day. In the gentle light of the early morning Rida, the gangly young waiter of Said Darwish’s café, crossed the empty square with tea for Hatem and me. Hatem still drank his tea with milk — a hangover from the UK that made the café staff snigger. Often, Hatem’s brother joined us (“And he never pays!” laughed Hatem). Sometimes, it was Amir, the man who delivered the rabbits. We would all sit together, observing the neighborhood wake up around us.

Someone dropped off their stale bread and we rose from our drowsy chitchat to feed it to the chickens, hearing stories about an unwell child, or a jealous wife. Hatem listened attentively to his visitors, occasionally interjecting with a consolation or a blessing. They left, Hatem’s father arrived, and we all began to work in earnest. Fifty chickens were slaughtered in quick succession. With Yusuf, a 17-year-old who worked part-time at the farargi, I learned how to soak the chicken carcasses in hot water to loosen their follicles so that the noisy machine in the corner could shake off their feathers. Hatem and his assistant Kemo stood at the counters carving the bald carcasses into legs and breasts, livers, and necks. Customers arrived, buying pre-prepared cuts or choosing a live animal that they wanted whole. They sat in a chair by the entrance and chatted to us as we washed and wrapped orders. Hatem was the energetic center of it all, trimming fat or slitting throats, never missing a beat in conversation, never resting, never eating — just milky tea and sweet coffee every few hours.

My presence in the butcher’s did not go unnoticed. Many local residents stopped to ask what I was doing, or to take photos of me as I worked. One assumed that I was a Syrian refugee. When I explained that I was English, she guffawed: “The situation in England must indeed be terrible for you to look for work in an Egyptian farargi!” I was nicknamed sha’r asfar (“Yellow Hair”) and became something of a local joke. But the laughter was affectionate, and I was happy to be the source of the enjoyment. Elderly women praised me for my hard work and complained that their own granddaughters were much too squeamish. I was stacking up marriage proposals as they offered me their sons or grandsons!

I still had a lot to learn, and Hatem was very patient. While trimming fat, I frequently nicked the meat and, almost as frequently, my own fingers. One morning, I disconnected the gas tubing to the de-feathering machine and almost set fire to the shop! Practical incompetence aside, I was constantly blundering into differences of culture. When I used the verb qatala (to kill) to refer to slaughter, Hatem vehemently corrected me. He told me that the proper verb was dhabaha, which means “to slaughter,” and, also, “to sacrifice.” I was puzzled but this distinction, and Hatem’s uncharacteristic firmness struck me as important. I wanted to understand it better. I started to carry a notebook and voice recorder whenever I went to Kom el-Dika, and I made time to sit with friends, customers, and shopkeepers, and ask them questions.

I began with people’s eating habits. Having felt the racing hearts of chickens as I weighed them, I was reevaluating my own attitude to eating meat (chicken, certainly, was having a hiatus in my cooking rotation). I wondered how the residents of Kom el-Dika felt about the animals they picked out for lunch.

Eating Meat, Or Not

When I asked about vegetarianism, Hatem’s customers either didn’t understand the concept or dismissed it out of hand. “That’s no good!” exclaimed Samar, a loud and affectionate woman who would often sit outside her husband’s grocery shop with her three sisters. “I believe there are people who don’t like eating meat, but us Egyptians — we love meat!” added Marwa, a sharp-tongued, sharp-witted woman from Nuba. She had worked as an English teacher and then married the only foreigner living in the area — an American teacher that had adopted the name Taymur. Some acknowledged that poverty or health problems may force some Egyptians to adopt meat-free diets, but they knew no one who was vegetarian by choice.

Trying another tack, I asked whether we had the right to eat animals. The mention of “rights” in relation to meat consumption tended to cause some confusion — huquq is mainly used in a political context —and the conversation turned instead to the topic of halal. “Because our God made them halal. Those he made halal, we can eat, and those he made haram, we don’t eat … It’s what God says,” said Mr. Said, another butcher. Over 100 years ago, his grandfather had opened Kom el-Dika’s oldest gazaara, which sold red meat from animals slaughtered in nearby halal abattoirs. Mr. Said was referring to passages in the Quran that distinguish the animals allowed for human consumption. Cows, goats, and chickens are halal (permitted) by Allah, while pigs and carrion are haram (not permitted). Other customers recounted the sura in the Quran in which God sends Ibrahim a lamb to sacrifice in place of his son Ismael. In traditional Muslim Kom el-Dika, the conversation around eating meat had different parameters than what I was used to.

I returned to Hatem’s insistence of the word dhabaha rather than qatala. The butcher does not kill, as I came to understand. Rather he sacrifices animals with the permission of Allah, as Ibrahim once did.

Halal Practice

To understand more about halal tradition and its connection to butchery, I sought out the neighborhood’s religious leader. Imam Gamal described the process to me: “You have to slaughter when you’re tahir.” In Islam, tāhara, a state of purity, is demanded in situations of ritual importance.

He continued, “The blade needs to be sharp, so the animal doesn’t suffer. Also, don’t show the animal the knife. Before you slaughter it, you must feed it and give it water — that’s sharia. And you must treat it with mercy and kindness. Caring about the animal is very important. And you must say the name of God … bismillah, Allahu akbar… If you don’t do all of this, it’s haram.”

Gaber, locally proclaimed as “the best pastry man in Alexandria,” went on to inform me: “They [animals] must be slaughtered legitimately, by sharia, with the name of Allah, bismillah al-rahman al-raheem. That’s mercy.” Versions of this answer echoed through many of the interviews: the principal obligations of halal slaughter are saying the name of Allah, and animal welfare.

But in practice, kind treatment of animals often comes into conflict with efficiency. According to Imam Gamal, animals should not see the knife before the slaughter to avoid causing the animal gratuitous distress. But in the farargi, space is limited, and this is unavoidable. While the Imam recognized it as problematic, he shrugged it off without much regret. Samar had an explanation; “That’s [the rule] for cows and sheep, not chickens.” When we spoke about the animal’s suffering, Hatem responded matter-of-factly, “The question isn’t about the feeling [of the animals], it’s about getting rid of the blood.” The Quran considers the consumption of blood as haram.

Dhabh

Months went by, and although my skills with the knife had been improving steadily, I felt that something was missing. I wanted to know the butchering process from beginning to end. I wanted to know how to slaughter. I asked Hatem if he would teach me.

It was clear that Hatem thought my request was eccentric, if not out of character, but he agreed readily enough. He told me to come to the shop very early the next morning, before most people had woken up. I was struck by this secretiveness and nervously asked him whether this was because I was not Muslim. Yes, Hatem acknowledged, this was one reason for his caution, but it was also that I was a woman, and there was a possibility that I could be menstruating. Menstruation would mean I was not in the required state of tahāra (purity).

Hatem’s response shocked me. In fact, it almost brought my apprenticeship to an abrupt end. Was it deceitful to serve halal meat without telling the customers that I had slaughtered it? And if we did tell them, would they reject the meat and resent me? Hatem obviously didn’t take issue with my religion or gender himself, otherwise he would not have agreed to teach me. Yet his comments made me fearful. What if I upset the community that had been so welcoming to me and lost the trust I had been working so hard to build? I needed to know more. How did the residents really feel about a non-Muslim slaughtering their animals?

The older generations seemed comfortable with the idea of a non-Muslim butcher. Gaber proclaimed that “One son of Adam is like another,” and others said that the butcher could be anyone from the ahl al-kitab (“People of the Book” i.e. Muslims, Jews, and Christians). Residents below 30 tended to be stricter. Samar, in her twenties, explained that meat slaughtered by any non-Muslim was haram. Sa’d, a fūl and falafel vendor of a similar age, agreed with her. The teenagers that I interviewed declared independently that Christians could perform halal slaughter, but not Jews. According to Yusuf, Jews were “the enemies of Islam” and fought against Muslims since its birth. Sandy — Hatem’s niece of 14 years and a close friend— explained to me that her attitude came from more recent political conflicts. “I’m not racist but we don’t deal with Jews,” she said. “You have to understand, there are no more Jews in Egypt. Today Jew means Israeli and Israel is our enemy.” Imam Gamal also recognized the prevalence of antisemitic feeling. “The people we love are Christians and most of our enemies are Jews … The Jews often killed our prophets.”

My family is Jewish. Although I have never practiced the faith or identified strongly with the culture, I found these views upsetting — particularly from Sandy, with whom I had formed a close bond. We spent Saturdays drinking mango juice along the Corniche. We called each other sisters. I battled over whether to say anything — any admission or defense — but my intention to remain inoffensive during my year abroad, my conviction to listen rather than to challenge, won over. Conviction or cowardice? Considering it now, I’m still not sure.

It seemed that my religion — or equally my lack of it — could jeopardize the halal status of the meat I prepared. What, then, of my gender?

Although locals insisted they knew of women working in farargi in other neighborhoods, in the five butcher shops of Kom el-Dika, there was only one other female employee apart from me. And Hind did not describe herself as a butcher; her job was to prepare and sell the meat that arrived pre-slaughtered from a farm every morning. In fact, Hind believed that the occupation of butcher was exclusively for men, and I soon found out how widely this attitude prevailed. During Ramadan, I attended an annual iftar meal hosted by a wealthy chicken supplier to Alexandria. It took place in one of the city’s outer neighborhoods. We broke the fast sitting at long tables stretching down the street, eating whole-roasted chickens (of course), potatoes and drinking hibiscus juice. Over a hundred people attended from all over Alexandria — butchers, butchers’ assistants, farmers, and delivery truck drivers. Apart from me, every single person there was male.

Why so few women in the industry? Physical strength was widely recognized as a factor, particularly when it came to gazaaras — by all accounts the animals were just too big. Emotional weakness and fear of blood also came up. Sa’d asserted that, “Women … don’t have gar’aa, the bravery, or the strong heart for slaughter.” Samar’s reason: “3aib.”

3aib

The term 3aib means “shame” or “shameful” (3aib 3layk — “shame on you”), and the more time I spent in Egypt I noticed how often it came up. Marwa explained it to me, “Here in Kom el-Dika a lot of things are 3aib, okay? People judge. A lot. There are traditions and customs.” 3aib can be used to describe an action as merely impolite or to condemn it as immoral. Marwa — a smoker herself — gave the example of women smoking in public as “3aib.” Not offering a guest food or drink could also be 3aib, as could calling an older woman by her first name rather than by her son’s. The way I came to see it, a code of conduct is established and if someone acts outside of that code, 3aib is generated. It involves the judgment of the community and the shame of the transgressor. Shared values and tradition are very important to the close-knit community of Kom el-Dika, which perhaps explains why alternative behavior is so firmly criticized.

Samar condemned women working in butchers as 3aib, but in the same breath she went on to praise the diligence of those women who rear, slaughter, and clean chickens at home. Marwa’s single female neighbor kept chickens on the roof of their apartment building, Marwa told me, and it drove their dog crazy. Gaber declared proudly that his wife slaughters all kinds of animals at home during the Eid holiday — chickens; rabbits; even goats! There was an inconsistency in women’s relationship to slaughter that I was unable to wrap my head around.

“In England, maybe it’s you, maybe it’s the man who works,” Ashraf clarified things to me over the counter of his farargi, a small place around the corner from Hatem’s. Ashraf was a garrulous and passionate man who encouraged me to convert to Islam every time that we sat down for tea … or at least to work for him instead! “Here, mainly it’s the men who work and the women who cook and prepare the food at home. So, the man comes back from work and eats.” This arrangement is familiar to many parts of the world. Men are active in the workplace — the public space — while women are active in the domestic realm — the private space. In the home, the woman can slaughter with no risk of 3aib. In this way, 3aib acts to preserve the division of labor according to the traditional gender roles.

The Dilemma

After all my conversations, my personal dilemma was still unresolved. Could I assume the unusual and potentially problematic position of a female, non-Muslim, halal slaughterer?

As a foreigner, I often felt (and often uncomfortably) that I existed outside local expectations. While working in Hatem’s butcher, I experienced none of the 3aib referred to in interviews. As I have described, the general reaction to my work was positive. It seemed that my “outsider” status meant that the eccentricity of my actions could be enjoyed without the fear that they could challenge the status quo. One could argue that my position gave me license to act (and slaughter) as I wished, unobstructed by local values. That argument tasted somewhat sour in my mouth — hadn’t I been striving to be part of something in Kom el-Dika? But then, allowing my actions to be dictated by 3aib that I neither felt nor ascribed to seemed somehow inauthentic…

I made my decision: I picked up the knife.

Hatem’s butcher — more than a bread shop, more than a patisserie — was a barometer of the community. The time of year, the health and wealth of the inhabitants: it was as though you could plot the currents of Kom el-Dika by the activity in Hatem’s shop.

Closing Time

Every evening, as we hosed everything down, the sounds from the café rang out into the falling light. Crowds of men smoked shisha, drank coffee, and played uproarious championships of backgammon. Sometimes we stopped by and watched the game, sometimes we headed over to Hatem’s parents’ place for a meal, or sometimes we just sat in the shop with whoever was around. One evening, I snuck in a couple of illicit cans of Guinness that had traveled over with my parents from the UK. Hatem pulled down the shop shutters early so that he could enjoy those nostalgic Irish draughts without scrutiny. But in the holidays, there was no time for such frivolity. During Ramadan, Hatem would work late into the night so that the neighborhood could break their fast with meat. To celebrate the Prophet’s birthday, he worked past midnight preparing 100 chickens that were to be distributed among the poor.

My time as a butcher’s assistant gave me a place in an unfamiliar city and proximity to its heartbeat. I experienced kindness and warmth I could not have hoped for. There were days when I would turn up for class — bleary-eyed from an early start, smeared with blood and chicken shit, fingers nicked and smelling bad— and I would think, “Why couldn’t I have stumbled into a bread shop? Or a patisserie? I could be smelling of flour and dates!” But Hatem’s butcher — more than a bread shop, more than a patisserie — was a barometer of the community. The time of year, the health and wealth of the inhabitants: it was as though you could plot the currents of Kom el-Dika by the activity in Hatem’s shop.

The greatest pleasure, the real reward which I had not expected, was the affection of Hatem and his family. Hatem may never have understood what on earth I was doing in his farargi, but he took me on and looked after me anyway. Initially, I think I offered Hatem a connection to his previous life in the British Isles; a welcome excuse to speak English! For me, Hatem acted as a gentle mediator between my own culture and the culture of Kom el-Dika. From this symbiosis, an unusual and beautiful friendship emerged.

What’s more, if you gave me a live chicken and a few minutes, I could hand you back some de-feathered, fat-trimmed, and wholly appetizing chicken legs. Or breasts. Or even a carefully cleaned stomach! Who says a degree doesn’t give you practical skills?